Targeted magnetic resonance imaging (tMRI) of small changes in the T1 and spatial properties of normal or near normal appearing white and gray matter in disease of the brain using divided subtracted inversion recovery (dSIR) and divided reverse subtracted inversion recovery (drSIR) sequences

Introduction

In the first study of multiple sclerosis (MS) with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 1981, an intermediate inversion time (TI) T1-weighted inversion recovery (IR) pulse sequence was used to produce high contrast visualization of lesions with increased T1s (1). This was followed by the use of long repetition time (TR), long echo time (TE) T2-weighted spin echo (T2-wSE) sequences in 1982 and 1983 to show lesions in MS and other diseases with high contrast as a result of their increased T2s (2-5).

In 1984, a Gadolinium based contrast agent (GBCA) was used with intermediate TI (TIi) T1-weighted IR sequences to provide high contrast in lesions as a result of the reduction in T1 produced by the GBCA (6).

In 1985, the short TI IR (STIR) sequence was described (7). For concurrent increases in T1 and T2 in lesions in disease, this sequence displayed synergistic contrast in which the contributions to lesion contrast from both the increases in T1 and T2 were complementary. This resulted in high contrast visualization of abnormalities in diseases of the brain and body.

In the same paper (7), the double IR (DIR) sequence was described in which two IR sequences with different TIs were multiplied together. The DIR sequence was used to simultaneously suppress signal from fat and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In addition, as with the STIR sequence, concurrent increases in the T1 and T2 of lesions produced high synergistic contrast. In 1994, the DIR sequence was used to suppress signal from white or gray matter in the brain, as well as CSF. In lesions with concurrent increases in T1 and T2, the sequence provides synergistic T1 and T2 contrast in gray or white matter respectively (8).

The T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR) sequence was described in 1992. It used a long TI (TIl) to suppress CSF signal and a long TE to increase T2 contrast since, for concurrent increases in T1 and T2 in lesions, the T1 contrast is opposed to the T2 contrast. The increased T2-weighting provided by the long TE is used to overcome this, and render the sequence T2-weighted for most lesions (9).

IR sequences including TIi IR sequences such as magnetization prepared-rapid acquisition gradient echo (MP-RAGE), GBCA enhanced TIi IR acquisitions, STIR and T2-FLAIR are key components of present day MRI protocols for the study of MS in the brain and spinal cord (10) as well as for tumors (11) and other diseases of the brain (12).

In 2010, in addition to the DIR sequence, another multiplied IR (MIR) sequence, magnetization prepared 2 rapid acquisition gradient echo (MP2RAGE), was described (13) and this has been used to visualize MS lesions in the brain and spinal cord with performance superior to conventional sequences (14,15). The MP2RAGE sequence uses changes in T1 twice to generate synergistic T1 contrast from two IR images with different TIs. The images are multiplied together, and the product is normalized by dividing it by the sum of the squares of the signals from both IR images. The sequence contrast is optimized for composite white-gray matter, white matter-CSF, and gray matter-CSF contrasts and uses two widely separated fixed TIs. This provides sensitivity to differences in T1 in normal and abnormal tissue over a wide domain of T1 values.

Subtracted IR (SIR) sequences with different TIs were described in 2017 and 2018 (16,17). The SIR sequence provides images with increased T1 dependent contrast compared with single IR sequences for T1s between the nulling values for the two TIs of the IR sequences. The TIs of the two IR sequences were narrowly separated and were varied depending on the tissue(s) of interest.

Variants of the fluid and white matter suppression (FLAWS) sequence in which two IR images with different TIs are subtracted, and then divided by the sum of the two images were described in 2019 and 2021 (18,19). These FLAWS high contrast (FLAWS-hc) and FLAWS-hc opposite (FLAWS-hco) sequences use two widely separate fixed TIs and provided T1 contrast over a wide domain of T1 values.

In four previous papers published in 2020 and 2022, a formalism was described to understand the signal, contrast and weighting of MRI pulse sequences using the concepts of tissue property filters (TP-filters) and the central contrast theorem (CCT) (20-23). This approach uses a quantitative definition of sequence weighting to understand the contrast produced by commonly used clinical sequences as well as more complex sequences. Combinations of two or more IR sequences were generalized as the multiplication, addition, subtraction, and/or division of IR (MASDIR) group of sequences. Contrast in these sequences was mathematically modeled using TP-filters and the CCT.

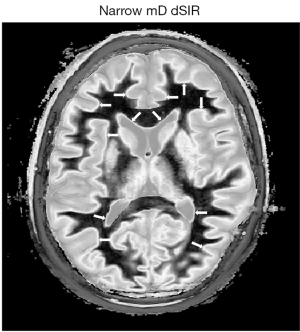

In modeling contrast produced by MASDIR sequences, two particularly interesting sequences were identified. These were forms of the divided SIR (dSIR) sequence in which two magnitude IR images with different TIs were subtracted and divided by the sum of the two images, and a variant of this, the divided reverse SIR (drSIR) sequence, in which the subtraction of the two IR images is performed in the reverse order. Both sequences employ differences or changes in T1 on 3–4 occasions to generate synergistic T1 contrast. The middle domain (mD) of the dSIR and drSIR sequences includes T1s between the nulled T1s of the original two IR sequences. When narrow mD versions of the dSIR and drSIR sequences were used, small changes in T1 produced 5–15 times the contrast seen with conventional MP-RAGE sequences. This was particularly well suited to demonstrating contrast due to small changes in T1 in normal or near normal appearing white matter (as shown with conventional T2-wSE and T2-FLAIR sequences). Using narrow mD dSIR sequences in cases of MS, extensive abnormalities were demonstrated in areas of normal appearing white matter [e.g., Fig. 31-35 in (23)].

Narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences are very sensitive to small changes in T1 within the narrow mD. This differs from MP2RAGE, FLAWS-hc, and FLAWS-hco sequences which are generally less sensitive to small changes in T1 than narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences in the mD, but are sensitive to changes in T1 over a wider domain of T1 values.

The term targeted MRI (tMRI) is used to describe sequences which are focused on a particular tissue and specific changes in one or more tissue properties (TPs) of that tissue such as T1 and T2. In this paper, the dSIR and drSIR sequences are targeted at small changes in T1 from normal in normal or near normal appearing white or gray matter. This requires use of TIs targeted at the nulling TIs of normal white and gray matter as well as different TIs to match the sign and size of changes in T1 expected in disease. This is different to MP2RAGE, FLAWS-hc, and FLAWS-hco sequences which use fixed TIs for all tissues and are not targeted at a specific tissue or specific changes in the T1 of that tissue in disease.

In addition to the production of high contrast from small changes in tissue T1 using narrow mDs described above, dSIR and drSIR sequences can produce high signal, often high contrast boundaries between tissues and fluids. (The term “tissues” is used to include tissues and fluids in the rest of this paper unless otherwise specified.)

dSIR and drSIR images are normalized, and are largely independent of mobile proton density (ρm) and T2 (which both cancel out in the dSIR and drSIR signal equations), and are therefore essentially T1 maps. In the mD, image signal is, to a first approximation, proportional to T1.

The drSIR sequence is very sensitive to small reductions in T1 produced by GBCAs and the sequence can be used with three-dimensional (3D) isotropic acquisitions and rigid body registration to eliminate misregistration between pre- and post-GBCA images, and show GBCA enhancement in normal and diseased tissue.

The high signal boundaries of dSIR and drSIR sequences can be used with rigid body registration to show small changes in spatial properties (e.g., site, shape, size and surface) of normal anatomical structures and lesions over time in serial studies. This is in addition to changes in T1.

The availability of T1 measurements and sharply defined boundaries with dSIR and drSIR sequences makes them well suited to quantification of T1 without or with GBCA enhancement, as well as the spatial properties of normal tissues and lesions.

The purpose of this article is to explain the background underpinning the use of dSIR and drSIR sequences to target small changes in the T1 and spatial properties of normal (or near normal) white matter or gray matter of the brain, describe implementation of the sequences and illustrate their use in clinical cases.

Theory

The spin echo (SE) sequence (univariate model)

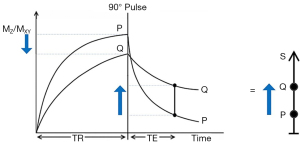

The usual explanation of image signal and contrast with the SE sequence utilizes a simplified version of the Bloch equations. This initially follows longitudinal magnetization (MZ) over time TR and, after the application of a 90° pulse, then follows transverse magnetization (MXY) over time TE (Figure 1). Contrast between two tissues such as P with a shorter T1 and T2, and Q with a longer T1 and T2, is shown by the vertical difference in MXY at the time of data collection TE, as shown by the vertical blue arrow on the right in Figure 1. MZ becomes MXY as a result of the 90° pulse used in the SE sequence.

The voxel signal S for a SE sequence is derived from the simplified Bloch equations where:

K is a scaling function, ρm is mobile proton density, t' is the variable time for the initial part of the sequence, and t" is the variable time for the latter part of the sequence. T1 and T2 are time constants. Eq. [1] describes ρm in the first segment, recovery of longitudinal magnetization (MZ) over time in the second segment (which is in parentheses), and decay of transverse magnetization (MXY) over time in the third segment. The equations in the second and third segments are of the forms y = 1 − e−x and y = e−x, respectively where x is a variable.

It is useful to replace the variables t' and t" in Eq. [1] respectively by the constant times of the SE sequence TR and TE, and to treat the two time constants T1 and T2 in Eq. [1] as variables. This changes Eq. [1] to:

or:

where the signals for the three segments , , and are given by:

The second and third segments in Eq. [2] are of the forms y = 1 − e−1/x and y = e−1/x respectively, since T1 and T2 are now variables. These forms are quite different from the forms y = 1 − e−x and y = e−x shown in the second and third segments of the Bloch equations in Eq. [1].

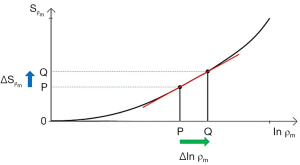

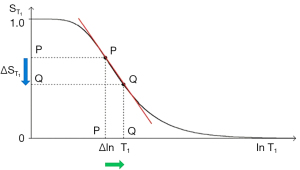

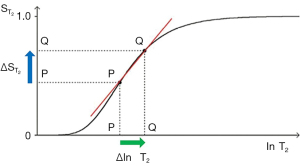

The three segments in Eqs. [2-6] have the features of a linear or exponential high pass filter for ρm [depending on whether the X axis is linear or natural logarithmic (ln)], a low pass filter for T1 (i.e., low values of T1 pass) and a high pass filter for T2 (i.e., high values of T2 pass) (Figures 2-4).

The signal levels on images are given by Eqs. [2-6] for , , and , and correspond to the signal or brightness of tissues seen on images.

Eqs. [2-6] can be plotted using ln X axes. When using a linear axis, changes in x (i.e., changes in ρm, T1, or T2) are absolute differences in TPs. When using a ln X axis as in Figures 2-4, small changes in x (i.e., Δln ρm, Δln T1, and Δln T2) represent fractional changes in TPs because for small differences in x, Δln x = Δx/x.

Figure 2 shows a ρm-filter in which the positive change in ρm Δln ρm from P to Q along the X axis (horizontal green arrow) is multiplied by the positive slope of the ρm-filter (red line) to give the positive change in signal from P to Q along the Y axis (vertical blue arrow). The change in signal is the absolute contrast Cab.

With the T1-filter shown in Figure 3, the positive change in T1 Δln T1 from P to Q along the X axis (horizontal green arrow) is multiplied by the negative slope of the T1-filter (red line) to produce a negative change in signal from P to Q along the Y axis (vertical blue arrow). The negative change is the negative contrast Cab.

The equation for Cab for small changes in ΔT1 and using a linear X axis is:

where is the first partial derivative of the T1-filter with respect to T1, which is the slope of the T1-filter, ∙ = multiplied, and ΔT1 is the change in T1 using a linear X axis.

Using a ln X axis, as in Figure 3 and noting that for small changes in T1, and that , where x is a variable, Eq. [7] becomes:

where is the slope of the T1-filter. This is the first partial derivative of the T1-filter with respect to (when using a ln X axis). ∙ = multiplied, and is the fractional change in T1 as shown in Figure 3.

For the T2-filter (Figure 4), the positive change in T2 from P to Q along the X axis (horizontal green arrow) is multiplied by the positive slope of the T2-filter (red line) and this results in the positive change in signal from P to Q along the Y axis and positive contrast .

Putting the second derivative of the T1- and T2-filters to zero yields the T1 or T2 value where the slope of the T2-filter, and therefore the contrast, is highest. For the T1- and T2-filters, the slope is greatest at TR = T1 and TE = T2 when using a ln X axis, and at TR = 2T1 and TE = 2T2 when using a linear X axis.

For fractional contrast Cfr = ΔS/S (rather than absolute contrast Cab = ΔS), Eqs. [7,8] are divided by and respectively for non-zero values of and .

So, for T1 using a ln X axis:

and for T2 using a ln X axis:

The SE sequence (multivariate model)

TP-filters can be considered separately [i.e., a univariate model for each TP (i.e., ρm, T1, and T2) alone, as in the previous section], or be combined in a multivariate model of the SE sequence as in this section. The multivariate model in Figure 5 shows the contributions to contrast of the change in each TP and the corresponding sequence weighting for each TP i.e., ρm, T1, and T2 (vertical blue arrows for each TP). The overall contrast (vertical blue arrow on the right) is the algebraic sum of the contrasts produced by each TP.

From Eqs. [3-6] for small change in Δρm, ΔT1, and ΔT2, and using a ln X axis, the product rule from differential calculus gives:

Normalizing Eq. [11] by dividing it by S and using Eq. [3], for non-zero values of S, , , and , Cfr is given by:

Thus, the contributions of the TPs to the overall fractional contrast Cfr are, for each TP, its sequence weighting multiplied by the fractional change in the TP.

This can be expressed as:

where 1/STP STP/∂ln TP is the sequence weighting for the TP which is the slope of the TP-filter. ΔTP/TP is the fractional change in the TP. The TPs are ρm, T1, and T2 for the SE sequence. Eq. [13] is one form of the CCT of MRI. Using a ln X axis, it states that the contrast for each TP is the normalized first partial derivative with respect to ln TP multiplied by the fractional change in TP. The total fractional contrast Cfr is the algebraic sum of the contributions to contrast from each TP.

When a single TP such as T1 is used, the contributions to T1 contrast from the different parts of the sequence need to be of the same sign to achieve overall contrast. With two different TPs, such as T1 and T2, their fractional contrasts also need to be of the same sign to achieve overall synergistic contrast. If one TP contrast is negative and the other is positive a reduction in overall Cfr results.

The IR sequence

The IR sequence has an additional T1-filter (segment) to those of the SE sequence shown in Figure 6. This IR T1-filter is:

where is the signal from the T1-filter, TI in the inversion time and T1 is the longitudinal relaxation time. The IR T1-filter is shown in phase-sensitive (ps) reconstructed form in Figure 6A where it is a low pass filter, and in magnitude (m) reconstructed form in Figure 6B where it is a notch filter.

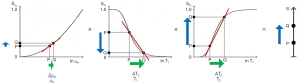

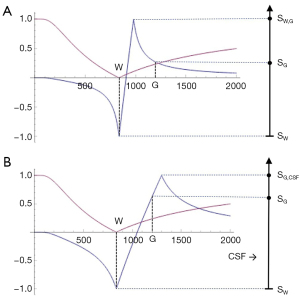

When TI is increased, the T1-filter shifts to the right as shown for the m form of the IR T1-filter in Figure 7. Figure 7A (left) shows the IR T1-filter with a short TI (TIs) (e.g., the STIR sequence) for the brain where gray matter (G) has a higher signal than white matter (W). The slope of the T1-filter between W and G is strongly positive.

When TI is increased to a TIi as in Figure 7B (center) the T1-filter is shifted to the right. W and G are fixed in the same position on the ln X axis, and W now has a higher signal than G. The slope of the T1-filter between W and G is strongly negative.

When TIl is increased further with a long TIl, the filter is displaced further to the right, as in Figure 7C (right). W has a slightly higher signal than G, and the slope of the T1-filter between them is negative but of smaller size than in Figure 7B. The sequence weighting of the T1-filter, which is the slope or first partial derivative of the filter, is highly positive in (Figure 7A), highly negative in (Figure 7B) and slightly negative in (Figure 7C) using a TIs (Figure 7A), a TIi (Figure 7B), and a TIl (Figure 7C) respectively.

Note that when the IR sequence TR is much greater than T1, the other T1-filter (1 − e−TR/T1) becomes ~1 and the principal determinant of T1 contrast is the (1 − 2e−TI/T1) T1-filter.

MASDIR sequences

Classification of MASDIR sequences

A classification of MASDIR sequences is shown in Table 1. They are separated into: (i) multiplied, (ii) added, (iii) subtracted, and (iv) divided groups (left column). More than one of the arithmetical operations (multiplication, addition, subtraction, and division) may be performed in a single sequence.

- MIR sequences: MIR sequences include the DIR and MP2RAGE sequences as described in the “Introduction” section;

- Added IR (AIR) sequences: one type of AIR sequence adds two magnitude (m) reconstructed sequences with different TIs and can be used with subtraction and division [see the (iv) section below];

- SIR sequences: the SIR and reverse rSIR sequences are included in this group. The SIR sequence uses the subtraction: shorter TI image minus longer TI image, and the rSIR sequence uses the reverse (r) subtraction: longer TI image minus shorter TI image;

- Divided IR (dIR) sequences (dSIR and drSIR): a central issue with division of IR sequences is the behavior of the T1-filter if, or when, the denominator takes a value of zero. This potentially leads to infinite values of the T1-filter. Even if zero values are avoided, there may be uncertain values when the denominator approaches zero and division becomes unreliable as a consequence of noise and/or artifacts.

Table 1

| Category | Examples of sequences (abbreviations) | Examples of sequences (fuller versions) |

|---|---|---|

| MIR | dIR | Double inversion recovery |

| MP2RAGE (also added in denominator) | Magnetization prepared 2 rapid acquisition gradient echo | |

| AIR | AIR | Added inversion recovery |

| SIR | SIR | Subtracted inversion recovery |

| rSIR | Reverse subtracted inversion recovery | |

| dIR | dSIR (also subtracted, and added in denominator) | Divided subtracted inversion recovery |

| drSIR (also subtracted, and added in denominator) | Divided reverse subtracted inversion recovery | |

| FLAWS-hc (also subtracted, and added in denominator) | Fluid and white matter suppression high contrast | |

| FLAWS-hco (also subtracted, and added in denominator) | Fluid and white matter suppression high contrast opposite |

MASDIR, multiplied, added, subtracted and/or divided inversion recovery; MIR, multiplied inversion recovery; dIR, double IR.

The problem can largely be avoided in the case of two magnitude IR images with different TIs (e.g., SIR and rSIR images) by making the denominator the addition (or sum) of the signals from the two images. Because the T1-filters have different TIs, when using magnitude reconstruction addition of them in the denominator is non-zero.

When the numerator is two SIR images, division normalizes the sequence so that to a first approximation, the effects of ρm and T2 are eliminated. As a result, dSIR and drSIR images are essentially T1 maps.

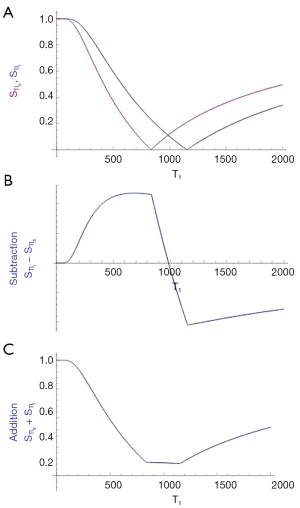

The bipolar dSIR T1-filter

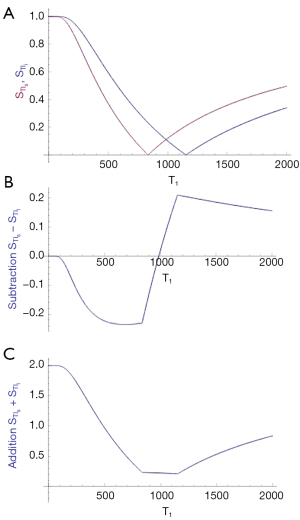

Two magnitude IR T1-filters with different TIs (TIs and TIi) are shown in Figure 8A. They are subtracted (TIs minus TIi) to give the SIR T1-filter in Figure 8B. The SIR T1-filter has a steep positive slope in the X axis region between the T1s corresponding to the two nulling TIs, i.e., in the mD. Subtraction of the negative slope of the TIi T1-filter from the positive slope of the TIs T1-filter produces a synergistic near doubling of the positive slope in the mD of the SIR T1-filter. The width of the mD is determined by the difference in TI between the two filters, ΔTI. Small ΔTIs give a narrow mD and large ΔTIs give a wide mD. ΔTI is the difference between the two TIs i.e., first reference, baseline or targeted tissue TI (mostly the nulling TI of the normal tissue) and the second TI chosen to match the targeted change in the sign and size of T1. By convention ΔTI is taken as the second TI minus the first TI and may be positive or negative. ΔTI is positive for dSIR T1-filters which have a positive slope and is negative for drSIR T1-filters which have a negative slope (see later). If ΔTI is the same sign as the change in T1 (ΔT1) contrast is positive. If ΔTI and ΔT1 are of opposite sign, contrast is negative. With the dSIR T1-filter targeted at normal appearing white matter and small increases in T1, ΔTI is the longer TI chosen to allow for an increase in T1 in disease, minus the shorter TI nulling normal white matter. Thus ΔTI is positive and so is ΔT1. This results in positive contrast.

The two T1-filters in Figure 8A can also be added as an AIR T1-filter which is shown in Figure 8C. There are higher signals and higher slopes outside of the mD. Within the mD there is a generally low signal with a nearly linear slightly downward sloping curve.

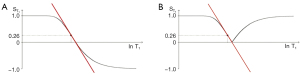

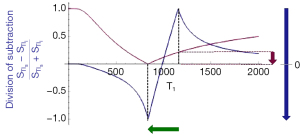

Figure 9A shows the dSIR T1-bipolar filter in which the SIR T1-filter in Figure 8B is divided by the AIR T1-filter in Figure 8C. The dSIR T1-bipolar filter shows a very high positive slope in its mD. The sloping mD in Figure 8B (the SIR T1-filter) was divided by the fractional value mD in the AIR T1-filter to greatly increase the slope shown in the mD of the dSIR T1-filter.

Figure 9B compares the contrast from the TIs T1-filter, (pink) which is that of a conventional IR sequence such as MP-RAGE, to that from a SIR T1-filter (blue). For the same positive change in T1 (positive horizontal green arrow in the mD, ΔT1) the vertical pink and blue arrows on the right show that the positive contrast produced by the SIR T1-filter is about double that produced by the T1-filter.

Figure 9C compares the contrast produced by a TIs T1-filter, (pink) to that from a dSIR T1-bipolar filter (blue). For the same positive change in T1 (positive horizontal green arrow in the mD, ΔT1) the dSIR T1-bipolar filter generates about 10 times the positive contrast produced by the T1-filter (vertical pink and blue arrows on the right). This follows directly from the CCT i.e., increasing the slope of the T1-filter increases the contrast produced by the same change in T1, ΔT1.

As the second TI is moved closer to the first TI, the magnitude of ΔTI decreases, the dSIR T1-bipolar filter becomes steeper in its mD, and the T1 dependent contrast generated increases for the same change in T1 (providing the change is within the mD). This is documented in Table 2. In this table, ΔTI is negative. As its magnitude decreases from 90% to 13% of the initial TI, the ratio of the contrast produced by the dSIR T1-bipolar filter to that produced by the conventional IR T1-filter increases from 5 to 20.

Table 2

| TIs (ms) | TIi (ms) | ΔTI | contrast | SdSIR contrast | Ratio SdSIR contrast/ contrast | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms | % | |||||

| 580 | 1,100 | 520 | 90 | 0.40 | 2.0 | 5 |

| 580 | 840 | 260 | 45 | 0.25 | 2.0 | 8 |

| 580 | 710 | 130 | 22 | 0.15 | 2.0 | 13 |

| 580 | 655 | 75 | 13 | 0.10 | 2.0 | 20 |

ΔTI is the second TI (1,100–655 ms) minus the first TI (580 ms) for the dSIR T1-bipolar filter, and is positive. As TIi is reduced from 1,100 ms (first row) to 655 ms (fourth row), the mD narrows and the magnitude of ΔTI decreases from 90% (first row) to 13% (fourth row). As the mD narrows and the magnitude of ΔTI decreases, the ratio dSIR contrast/ contrast increases from 5 (first row) to 20 (fourth row). TIs, short TI; TI, inversion time; TIi, intermediate TI; dSIR, divided subtracted inversion recovery; mD, middle domain.

Figure 9C also shows sequence targeting. The T1 X axis has low, middle and high domains separated by the vertical dashed lines. The T1-filter of the conventional IR sequence (pink) has a mostly non-zero slope and is sensitive to changes in T1 in all three domains including T1 values from near zero to the maximum value of T1 shown.

The dSIR T1-bipolar filter (blue) has a generally similar slope to the conventional IR T1-filter in the first domain and in the third domain (though of opposite sign there). In the mD however, the slope of the dSIR T1-bipolar filter is about 10 times higher than that of the conventional IR filter. As a result, the positive contrast produced by it is 10 times greater for the same change in T1. This increase in positive contrast is confined to the mD. To exploit the increased contrast, TIs need to be chosen to place the mD of the dSIR T1-bipolar filter in a position to target the change in T1. To do this for normal white matter, the first TI of the dSIR T1-bipolar filter needs to correspond to the normal value of T1 of white matter to achieve nulling. The second TI needs to be chosen to target the sign and size of the change in T1 that is expected. In Figure 9C the dSIR T1-bipolar filter is targeted firstly to null normal tissue, and secondly to produce positive contrast from the positive change in T1 from normal (positive horizontal green arrow, ΔT1). The size of ΔTI is sufficient to include the change in T1 i.e., the extent of the horizontal green arrow.

If the change in T1 (ΔT1) is negative as in Figure 10 (negative horizontal green arrow, ΔT1), and ΔTI is positive (as for the dSIR T1-bipolar filter), the resulting contrast is negative (vertical blue arrow on the right). It is about 10 times the size of the contrast produced by the conventional IR sequence (vertical pink arrow on right).

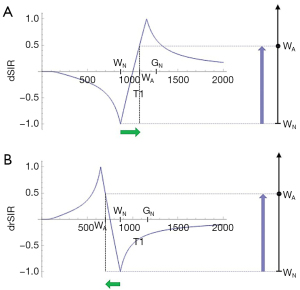

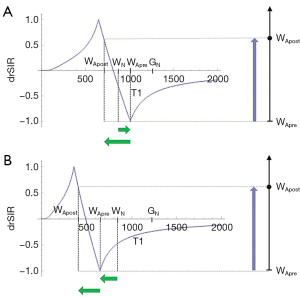

The bipolar drSIR T1-filter

Figure 11A shows the same two magnitude IR T1-filters with signals and as in Figure 8A. In Figure 11B the r subtraction rSIR T1-filter is shown (i.e., minus ). This has a negative slope in the mD. Figure 11C shows addition of the two original IR T1-filters to give the AIR T1-filter. Figure 12A shows the rSIR T1-filter in Figure 11B divided by the AIR T1-filter in Figure 11C which gives the drSIR T1-bipolar filter. This has a steep negative slope in the mD and a negative ΔTI. Figure 12B shows a comparison of the T1-filter (pink) with the rSIR T1-filter (blue) for a decrease in T1 as may be seen with hemorrhage, iron accumulation and GBCA administration (negative horizontal green arrow, ΔT1). The positive contrast produced by the rSIR T1-filter is about twice that of the T1-filter (vertical pink and blue arrows on right). Figure 12C shows a comparison of the T1-filter (pink) with the drSIR T1-bipolar filter (blue) for the same negative change in T1 (negative horizontal green arrow, ΔT1). The positive contrast produced by the drSIR T1-bipolar filter is about 10 times greater than that obtained with the T1-filter (vertical pink and blue arrows on right). In this case, the drSIR T1-bipolar filter is targeted to produce positive contrast from the negative change in T1.

If the change in T1 (ΔT1) is positive, as in Figure 13, then the negative ΔTI of the drSIR T1-bipolar filter, coupled with the positive ΔT1 means that the contrast is negative (vertical blue arrow on right). It is about 10 times the size of the negative contrast produced by the conventional IR sequence (vertical pink arrow on right).

Synergistic contrast MRI (scMRI)

Synergistic contrast arises in two main ways:

- A single TP can be used twice or more in a sequence to increase contrast. For example, changes in T1 can be used in the T1 dependent TR segment of an IR sequence as well as the T1 dependent TI segment. Changes in T1 are also used twice in the SIR sequence when employing the subtraction: TIs T1-filter minus TIi T1-filter. T1 changes are also used twice in the rSIR T1-filter with the reverse subtraction. The synergistic T1 contrast from the SIR and rSIR sequences can be increased further by using T1 changes 3–4 times by employing division with them as for the dSIR and drSIR sequences;

- Two or more different TPs can also be used to produce synergistic contrast as was first described with the STIR sequence in 1985 (7). Clinical pulse sequences have a basic structure consisting of ρm, T1, and T2-filters as seen in SE sequences. There are additional options which can be added such as those for T1 dependent inversion pulses and apparent diffusion coefficient (D*) sensitization. In many circumstances ρm is a minor determinant of contrast and T1, T2, and D* are major determinants.

The most common change in TPs in disease is concurrent increases in ρm, T1, T2. In this situation with the SE sequence, the contrast developed by an increase in T1 is negative while the contrast developed by an increase in T2 is positive, so that simultaneous increases in T1 and T2 produce opposed contrast and the net, or overall, contrast is reduced. To avoid this problem, T1-weighted SE sequences use a short TE to minimize the opposed T2 contrast, and T2-weighted SE sequences use a long TR to minimize the opposed T1 contrast. The dominant source of contrast in the resulting sequences is then a single TP, i.e., T1 or T2 and the sequences are described as T1-weighted or T2-weighted respectively. T1 and T2 are each used only once to create contrast in both sequences, and so the sequences are not synergistic for T1 and T2 contrast.

In particular circumstances, such as certain forms of the STIR and the DIR sequences, the T1 contrast produced by an increase in T1 is positive, and so is the T2 contrast produced by an increase in T2. The effects of concurrent increases in T1 and T2 are therefore synergistic, and typically result in high positive lesion contrast.

The synergistic contrast produced above from (i) a single TP, and/or (ii) two or more different TPs can be supplemented by increasing or decreasing signals from normal tissues and/or fluids. There may be little contrast between high signal lesions and high signal fat, long T2 tissues, or fluids. Reduction in the normal signal from these tissues or fluids [using the same or different TPs as those used to create the original synergistic contrast in (i) and/or (ii)] can increase the contrast between the high signal lesions and the zero or low signal suppressed tissues and/or fluids.

Contrast at tissue boundaries

In the previous sections of this paper, contrast between two pure voxels each containing a pure sample of a different tissue has been considered, but there has been no reference to the location of the voxels, contrast at boundaries between two voxels, or contrast within transitional regions between the two pure voxels where there are mixed voxels containing mixtures of the two different tissues (i.e., there are partial volume effects).

In general terms, contrast detectability at boundaries between two pure voxels with different values of S can be related to contrast Cab = ΔS or Cfr = ΔS/S divided by the distance Δx between the two pure voxels. Boundaries are more detectable when contrast is high and Δx is low, and less detectable in the opposite situation, where contrast is low and Δx is high.

In boundary regions between two pure tissues P and Q it is useful to define the tissue fraction (f) which is the proportion of the second tissue Q in a mixed voxel which contains a mixture of both tissues. The proportion of the other tissue P in the mixed voxel is then (1 − f).

The T1 of a mixture of the two tissues (P and Q) in a voxel can be expressed as a function

where T1P,Q is the T1 of the mixture, T1P is the T1 of P, and T1Q is the T1 of Q.

It is also useful to consider the change in tissue fraction with distance x. This may be gradual and correspond to a low value of , or be abrupt and correspond to a higher value of .

Using the chain rule from differential calculus, normalized contrast over distance for T1 is given by:

where is the change in fractional contrast with distance x, is the T1-filter signal, is a measure of detectable contrast at a boundary, is the first partial derivative of with respect to T1, i.e., the sequence weighting, is the change in T1 with tissue fraction (f), and is the change in f with distance x (Table 3).

Table 3

| † | ||

|---|---|---|

| Increasing T1 sequence weighting from lower (first row) to higher (fourth row) (below) | Increasing value from lower (first row) to higher (third row) (below) | Increasing value from lower (first row) to higher (second row) (below) |

| SGE | White matter-gray matter | Gradual |

| IR | Gray matter-CSF | Abrupt |

| SIR | White matter-CSF | |

| dSIR |

†, sequence weighting = slope of T1-filter. SGE, spoiled gradient echo; IR, inversion recovery; SIR, subtracted inversion recovery; dSIR, divided subtracted inversion recovery; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Thus, contrast at a boundary depends on the sequence weighting, the change in T1 with tissue fraction and the change in tissue fraction with distance. The change in tissue fraction with distance may be abrupt in one plane, but gradual in another plane.

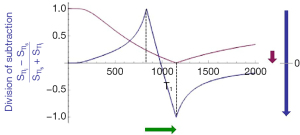

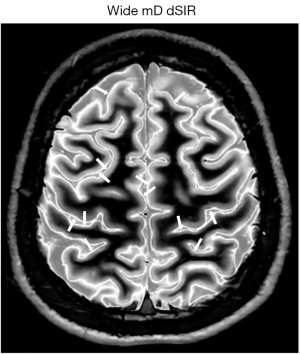

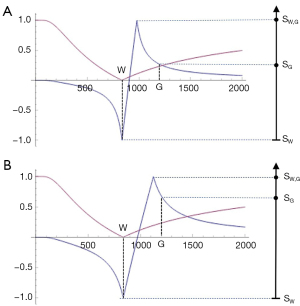

At a boundary between two pure tissues, the T1s of mixed voxels typically span the range of T1 values between those of the two pure tissues. If the T1-bipolar filter has a narrow mD so that a T1 value between those of white and gray matter produces a peak of the T1-bipolar filter SW,G, as in Figure 14A, this results in a high signal narrow line at the boundary between white and gray matter. This high signal boundary is inside the brain and is obtained using a narrow mD. If a wide mD is used as in Figure 14B, the peak signal SG,CSF occurs at a T1 between those of gray matter and CSF where there are mixtures of gray matter and CSF in voxels. As a result, the high signal boundary appears outside the brain. A boundary inside the brain is shown in Figure 15 and one outside the brain is shown in Figure 16.

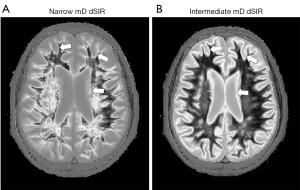

The width of boundaries seen on dSIR images can be changed by changing the width of the mD. Change from a narrow mD (Figure 17A) to an intermediate mD (Figure 17B) widens the peak region of the T1-bipolar filter and increases the width of the boundary. Figure 18 shows a comparison of an image obtained with a narrow mD (Figure 18A) with one obtained using an intermediate mD (Figure 18B). The white matter gray matter boundaries are narrow in Figure 18A and intermediate in Figure 18B (compare the paired white arrows in Figure 18A,18B).

In using a dSIR sequence with white matter nulled by the first TI, when the second TI is increased and approaches that for nulling gray matter, the contrast between the high signal boundary and gray matter is reduced. When the second TI becomes the same as that for nulling gray matter, the high signal boundary merges with gray matter. To create a high contrast boundary with gray matter (as well as with white matter) in this situation, the second TI needs to be significantly shorter than the TI which nulls gray matter.

The high signal boundaries between white matter and gray matter on dSIR and drSIR images are characteristic of this type of imaging. Their presence provides validation of the use of T1-bipolar filters to describe the signal and contrast behavior of the dSIR and drSIR sequences.

T1 maps

The signals Ss and Si for two long TR IR magnitude T1-filters with TIs and TIi as shown in Figures 8A,11A are respectively given by:

and

Performing the subtraction: magnitude of the IR signal in Eq. [17] minus magnitude of the IR signal in Eq. [18] gives the signal of the SIR filter SSIR which is equal to i.e.,:

Addition of the magnitudes of the two IR signals and in Eqs. [17,18] SAIR is equal to i.e.,:

Division of the signal of the subtraction T1-filter SSIR in Eq. [17] by the signal of the addition T1-filter SAIR in Eq. [18] gives the signal of the SdSIR T1-filter:

While this expression is accurate, it does not provide easy insight into the properties of the dSIR T1-filter. To do this, a linear equation of the form y = mx + c between the end points of the mD can be produced by fitting a straight line between the first and last points of the mD (i.e., first point x = TIs/ln 2 and y = −1, and last point x = TIi/ln 2 and y = + 1). It is an approximation to the dSIR T1-filter in the mD, so SdSIR in the mD is given by:

where ∆TI = TIi − TIs (i.e., second longer TI minus first shorter TI which is positive) and ΣTI = TIs + TIi. The convention for ΔTI is to define it by the subtraction: second TI minus first TI so ∆TI is positive for dSIR T1-bipolar filters and negative for drSIR T1-bipolar filters. The sign of ∆TI depends on whether the second TI is greater or less than the first TI. Note that because ΔTI is positive, and the slope in Eq. [22] is positive (e.g., Figure 9C) the contrast is positive.

The same approach applies to the drSIR T1-bipolar filters where the first point is x = TIi/ln 2 with y = −1, and the second point is x = TIs/ln 2 with y = 1. SdrSIR in the mD is given by:

where ΔTI = the second TI, TIs − the first TI, TIi which is negative, and . Since ΔTI is negative, the slope in Eq. [23] is negative (e.g., Figure 12C) and the contrast is positive.

The expressions in Eqs. [22,23] capture four key features of the dSIR and drSIR T1-bipolar filters, firstly, the near linear change in signal with T1 in the mD, secondly, the T1-bipolar filters have slopes equal to , and thirdly, the T1-bipolar filters show high contrast sensitivity for small changes in T1 when the size of ∆TI is small (since and ). As ΔTI decreases in magnitude, amplification of contrast increases (Table 2). Fourthly the equations can be used to map T1 in the mD since for SdSIR and SdrSIR:

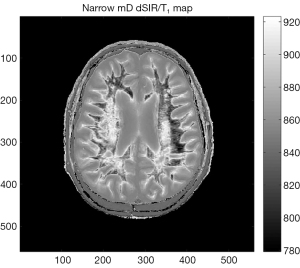

The SdSIR and SdrSIR maps typically show high contrast and high spatial resolution (e.g., Figure 19).

The linear approximation is only valid in the mD. Also, it is assumed that TR is long otherwise T1 values may require correction for incomplete recovery of longitudinal magnetization during TR. It is also assumed that the nulling of the baseline tissue is accurate.

GBCA enhancement

The effect of GBCA is to decrease T1 (i.e., produce a negative ΔT1) so, in order to see positive contrast enhancement, drSIR sequences are used as shown in Figures 11,12.

The baseline tissue may be normal or abnormal. In the latter case, its T1 may be prolonged and so the initial TI may need to be lengthened to correspond to this and thus be greater than that for normal tissue.

There is interest in both the image contrast produced by the GBCA and the specific effect of the agent itself. The image contrast may be demonstrated by appropriate choice of ΔTI. The specific effect of the agent can be found from the subtraction: post minus pre with the same IR sequence i.e., the baseline nulling sequence.

It is possible to choose several TIs so that image contrast increases can be observed in several tissues simultaneously.

The process of intravenous injection of a GBCA usually displaces the head between pre and post GBCA acquisitions relative to the scanner. 3D isotropic acquisitions with rigid body registration are a preferred way to deal with the resulting misregistration.

The focus is on subtle GBCA contrast enhancement including the types that delayed and double dose contrast agent regimes have been used for. It may also be possible to use lower doses of GBCAs.

Dynamic contrast enhancement and modeling of GBCA distribution may be improved by having greater sensitivity to T1 shortening produced by smaller quantities of GBCAs early in the enhancement process.

GBCA enhancement may be seen in CSF using the T2-FLAIR sequence as a baseline, but inflow of CSF during TI may produce shortening of the effective T1 of CSF and be a confounder. This can be addressed with a thicker slice, or non-slice selective inversion pulses (24).

Serial studies

In general terms, there is no special premium in clinical MRI in demonstrating high contrast lesions with even greater contrast. The emphasis with MASDIR sequences is on demonstrating contrast in situations where there are only small changes in TPs and, as a consequence, little or no contrast is seen with conventional sequences. The emphasis is therefore on imaging regimes which detect small changes in TPs. Ideally these can allow disease to be monitored over time to follow its natural history and the effects of treatment.

Increased sensitization in the mD is produced by a decreased width of the mD and decreased magnitude of ΔTI. This is particularly appropriate for detecting small changes in T1 from normal to abnormal in specific tissues. These changes may be seen in earlier stages of disease as well as in more subtle forms of disease.

In addition to contrast due to differences or changes in T1 as above, magnetic resonance (MR) images may show differences in signal (or contrast), due to differences in the spatial properties of tissues e.g., their size, site, shape and surface. This applies to normal and abnormal tissues.

The changes from normal in signal and space seen in a single image may vary over time in serial studies as part of the natural history of the disease and/or the result of therapy. In situations where the changes in signal and/or space are small, rigid body registration can accurately align images obtained on two or more examinations so that genuine changes can be distinguished from artefactual differences due to variation in slice alignment at the different examinations (i.e., misregistration).

This has been performed with 3D isotropic spoiled gradient echo (GE) sequences, and a system of interpreting subtracted images has been described (25). MASDIR sequences using 3D MP-RAGE or brain volume (BRAVO) type data acquisitions with rSIR or drSIR image processing offer increased sensitivity to changes in T1 compared with spoiled GE sequences. They also offer high signal boundaries to improve detection of changes in the spatial properties of tissues. This option is not available with spoiled GE sequences.

A major advantage with serial studies is that the patient may act as her/his own control with the initial images providing a baseline to recognize small changes in T1 and/or image spatial properties on subsequent examinations using registration. These might not be recognizable on a single image seen in isolation.

Quantitation

The fact the dSIR and drSIR images can directly provide values of T1 in the mD is valuable for quantitation. This can include decrease in T1 due to GBCA enhancement. In addition, the high signal boundaries are of value in quantifying spatial properties of normal tissues and lesions such as the volume of lesions or parts of them (as well as changes in volumes) in serial studies.

Summary of key concepts affecting the understanding and use of rSIR and drSIR sequences

Targeting

- In this work, tMRI is typically aimed at small changes in T1 and the spatial properties from normal in single tissues;

- The tissues of interest are normal or near normal appearing white or gray matter;

- The changes in T1 and spatial properties may arise from disease of the brain or other causes (e.g., physiological changes, contrast agents and drugs);

- The normal or near normal appearances of white or gray matter are usually those shown with MP-RAGE, T2-wSE, and/or T2-FLAIR sequences;

- For small changes in T1 from normal, narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences can usefully produce contrast up to about 15 times greater than that generated by conventional MP-RAGE sequences, and so make the effects of small changes in T1 visible on dSIR and drSIR images when they are not seen on conventional images;

- The dSIR and drSIR sequences need to be targeted to the T1 of the normal tissue for nulling as well as the sign and size of the change in T1 being sought. This is done by appropriate choice of their TIs, i.e., the nulling TI and the difference in TI, ΔTI are matched to the change in T1, ΔT1.

Mathematical modeling

- The modeling employs TP-filters which are plots of signal against TP or ln TP for segments of sequence or sequences;

- The contrast generated by a small change in a TP is the change in that TP multiplied by the slope of its TP-filter. The overall fractional contrast produced by a sequence is the algebraic sum of the contrasts generated by each TP in that sequence. This is expressed as the CCT. It is derived from the Bloch and Torrey equations using the product rule of differential calculus;

- The single TP T1 is used 3–4 times to generate synergistic T1 contrast with the dSIR and drSIR T1-filters;

- The bipolar T1-filters of the dSIR and drSIR sequences are used to describe the targeting, signal, contrast, boundaries, T1 mapping and GBCA enhancement of the two sequences;

- The contrast at boundaries (change in signal ΔS with distance x) is the product of the sequence weighting (slope of the T1-filter), the change in T1 with tissue fraction (f) and the change in f with distance x. This follows from the chain rule of differential calculus;

- In the mD of the dSIR and drSIR T1-filters, there is a near linear relationship between signal and T1 so dSIR and drSIR images can be calibrated as T1 maps in the mD. When the magnitude of the difference in TI (ΔTI) is decreased, contrast amplification is increased until the stage is reached where images become noise and/or artefact limited.

Radiology

- Contrast: contrast can be targeted at normal or normal appearing white or gray matter and can be produced where it is particularly needed i.e., for improving visualization of subtle disease where there are only small changes in T1 from normal, so that contrast is not shown, or only poorly shown, with conventional sequences;

- Boundaries: the dSIR sequence can produce high signal, often high contrast boundaries between white and gray matter, between white matter and CSF, between cortical gray matter and CSF, as well as between normal and abnormal tissues;

- T1 maps: because of the normalization of signals with dSIR and drSIR images, ρm and T2 effects are largely eliminated so dSIR and drSIR images are essentially T1 maps. There is a near linear relationship between signal and T1 in the mD which can provide direct reading of T1 values in areas of interest;

- GBCA enhancement: the narrow mD drSIR sequence is highly sensitive to reductions in T1 produced by GBCAs;

- Serial studies: using rigid body registration of isotropic 3D images, changes in T1 can be demonstrated. On registered images, the high signal boundaries produced by the dSIR and drSIR sequences can also be used to demonstrate changes in the spatial properties (e.g., size, shape, site, surface) of normal structures and lesions over time in serial MR examinations;

- Quantitation: dSIR and drSIR images provide direct measurement of T1 in the mD. This can be extended to GBCA enhancement including modeling of its distribution. T1 measurements can be supplemented by quantitation of spatial features using the high signal boundaries produced by dSIR and drSIR sequences.

Implementation of dSIR and drSIR sequences and their failure modes

Implementation

The source sequences for dSIR and drSIR images are typically conventional two-dimensional (2D) IR fast SE (FSE) and 3D IR GE (e.g., 3D MP-RAGE, BRAVO, or 3D fast field echo) sequences which are available on most clinical MR systems. The TEs are typically short e.g., 5–10 ms for FSE and 1–5 ms for GEs (Table 4). Comparable or slightly higher spatial resolution conventional sequences were performed for comparison using the same types of data acquisition.

Table 4

| # | Sequence | TI (ms) | TE (ms) | Matrix and voxel size (mm) | Slice thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2D FSE IR (for white matter nulling) | 350 | 7 | 256×224; Z512; 0.4×0.4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2D FSE IR (used with #1 for narrow mD dSIR) | 500 | 7 | 256×224; Z512; 0.4×0.4 | 4 |

| 3 | 2D FSE IR (used with #1 for intermediate mD dSIR) | 650 | 7 | 256×224; Z512; 0.4×0.4 | 4 |

| 4 | 2D FSE IR (used with #1 for wide mD dSIR) | 800 | 7 | 256×224; Z512; 0.4×0.4 | 4 |

| 5 | 3D BRAVO with prospective motion correction (PROMO) (for white matter nulling) |

350 | 2.8 | 240×240; 1×1 | 1 |

| 6 | 3D BRAVO with prospective motion correction (PROMO) (used with #5 for narrow mD dSIR) |

450 | 2.8 | 240×240; 1×1 | 1 |

| 7 | 3D BRAVO with prospective motion correction (PROMO) (used with #5 for intermediate mD dSIR) |

650 | 2.8 | 240×240; 1×1 | 1 |

| 8 | 3D BRAVO with prospective motion correction (PROMO) (used with #5 for wide mD dSIR) |

750 | 2.8 | 240×240; 1×1 | 1 |

| 9 | 2D T2-wSE | 2,200 | 102 | 300×280; Z512; 0.5×0.5 | 4 |

| 10 | 3D T2-FLAIR | 1,851 | 102 | 256×256; Z512; 0.5×0.5 | 0.8 |

TI, inversion time; TE, echo time; 2D FSE IR, two-dimensional fast spin echo inversion recovery; Z, zipped; mD, middle domain; dSIR, divided subtracted inversion recovery; 3D BRAVO, three-dimensional brain volume; 2D T2-wSE, two-dimensional T2-weighted spin echo; 3D T2-FLAIR, three dimensional T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery.

In targeting the source IR images, the initial task is to select the tissue of primary interest and determine the TI needed to null it (Figure 20). The choice of TI may be based on a knowledge of tissue T1s and nulling TIs, experience with similar cases and recognition of the technical factors which change the nulling TI as well as conditions which change the T1 of tissues to be nulled [see Tab. 8 in (23)].

In general, at least initially, it is worth testing to ensure that the tissue of interest is nulled and, if there is doubt, when seeking changes that increase T1 use a TI slightly less than the expected value. Errors in this direction generally have a benign effect on contrast.

The next decision is the expected sign of the change in T1 i.e., positive or negative. This determines whether the second TI used is higher (increase in T1) or lower (decrease in T1 than the nulling TI. After this, a decision needs to be made on the magnitude of the difference in TI i.e., ΔTI. Smaller TIs give higher amplification of contrast but if the change in T1 takes it outside the mD this results in overshoot. ΔTI determines the width of the mD which may be narrow, intermediate or wide. For white matter, using a dSIR sequence and seeking an increase in T1 with a longer second TI, a narrow ΔTI is about 20% to 40%, an intermediate ΔTI is about 40% to 60%, and a wide ΔTI is about 80% or more. The objective is to match the position and size of the mD to the position, sign and size of the change in T1 so that the sequence is correctly targeted.

When targeting white matter, the choice of narrow, intermediate or wide mD also determines the location of high signal boundaries. If the second TI is less than that needed to null cortical gray matter, the high signal boundary will be within the brain between white matter and cortical gray matter. If the second TI is greater than that needed to null cortical gray matter the boundary will be outside of the brain at the junction between cortical gray matter and CSF.

For other tissues the location and width of the high signal boundaries follows from the same considerations as in Figures 14,17. Narrow boundaries are found with small magnitudes of ΔTI and narrow mDs. Wider boundaries are found with larger magnitudes of ΔTI and wider mDs.

The image processing uses the images acquired with the two different TIs, and does the subtraction: shorter TI image minus longer TI image to give SIR images and the reverse subtraction: longer TI image minus shorter TI image to give rSIR images. The two original images are then added to give an AIR image which is used in the denominator to divide the SIR and rSIR images to give dSIR and drSIR images respectively. This is performed for both 2D and 3D images.

For GBCA enhancement there is usually displacement of the patient’s head between pre and post contrast images relative to the MR system, so 3D isotropic GE acquisitions are used, and rigid body registration is used to align the pre and post images and allow subtraction without misregistration. drSIR sequences are used and the initial nulling TI for contrast enhancement may need to be prolonged if a lesion with an increased T1 is being studied, or shortened if a lesion with a decreased T1 is being studied (Figure 21). Subtractions performed after GBCA administration may be targeted at (i) image contrast and (ii) specific effects of the GBCA.

In serial studies performed at different times, in addition to changes in signal and contrast there may be changes in space (e.g., change in site, shape, size and surface of normal tissues or lesions as with growth or regression of a tumor). If the changes are relatively small, rigid body registration can also be used to precisely align images obtained at different times. This is often the situation with dSIR and drSIR images when they are used for detection of small changes in T1 and/or spatial properties. If changes are large, non-rigid body registration may be needed. This is less precise than rigid registration, but if the changes are large, image interpretation is usually straightforward.

Failure modes

Failure modes need to be recognized, preferably at an early stage so the rest of the examination is not compromised.

- The commonest problem is failure to null the normal tissue of primary interest. Usually, the TI is too long and this reduces the contrast produced on dSIR images when nulling white matter and seeking an increase in T1 in disease. The precise value of TI for nulling can vary for technical reasons e.g., with field strength, the value of TR, the recovery time, the efficiency of the B1 pulse, B1 homogeneity, data collection (GE vs. FSE) use of fast recovery and fat saturation. The T1 of the tissue to be nulled can vary with subject age, location in the brain etc. Cancellation lines are seen at the boundary between two tissues on magnitude images when the longitudinal magnetization of one tissue is positive and the other is negative. They occur when white matter is being nulled if the TI being tested for nulling is too long so that the 90° pulse and sampling is too late. The white matter longitudinal magnetization (Mz) is then positive (not zero as it would have been if the white matter had been nulled) and gray matter Mz is negative. If the TI is too short, both the white and gray matter have negative Mzs. As a result, there is signal on magnitude images, but no cancellation line between the two tissues;

- It is also possible to choose the wrong sign for the change in T1 in disease e.g., be set up for an increase in T1 and the disease produces a decrease in T1;

- The mD may be too narrow leading to signals which overshoot the mD of the dSIR or drSIR sequences. This occurs when the changes in T1 are greater than expected. With dSIR sequences set up for an increase in T1, it typically results in a high signal around the lesion with intermediate signal inside the boundary;

- The mD may be too wide leading to low contrast for the change in T1;

- The boundary location and width may be inappropriate. If the first TI is chosen to null white matter, and the second TI is chosen to null gray matter, the boundary between the two may be isointense with gray matter and so may not be apparent;

- Misregistration is usually obvious, with for example high and low signals at lateral ventricular boundaries. Correction of misregistration with 2D images may be possible to a reasonable degree with shifting of the second image by a few voxels and/or fractions of a voxel. Rigid body registration of isotropic 3D images is usually a more satisfactory solution;

- Partial volume effects from high signal boundaries may simulate lesions particularly with 2D acquisitions using a thick slice e.g., 3–4 mm compared with the typical 1 mm slice thickness of 3D acquisitions;

- Errors in T1 may arise from:

- inaccurate tissue nulling;

- use of a short TR;

- measurement outside of the mD;

- It may be useful to label accurate T1 values in the mD on images by color, or use a mask to separate them from inaccurate T1 values outside of the mD;

- The MP-RAGE sequence has limitations on the TI needed to achieve white matter nulling imposed by the minimum TR which are not found with the BRAVO sequence. Increasing the TR may resolve the problem by making shorter TIs accessible.

Examples

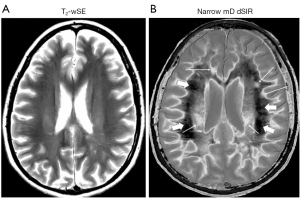

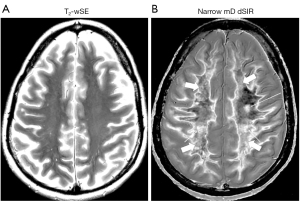

Application of these principles can be seen in a case of MS (Figure 22) which compares a T2-wSE image (Figure 22A) with a narrow mD dSIR image (Figure 22B). This image (Figure 22B) is targeted to null normal white matter and produce high positive contrast from small increases in white matter T1 from normal. No abnormality is seen in (Figure 22A) but three focal lesions are seen in (Figure 22B) (long thin arrows). One is in white matter; another is at the junction between white and gray matter (anterior); and the other is at the junction between white and gray matter but mostly in gray matter (left). Localization of lesions is helped by the well defined high signal white matter gray matter boundaries. High signal is seen in the corticospinal tracts (short thin arrows). Normal white matter is seen laterally and has a low signal (dark) appearance in (Figure 22B) (thick arrows). Intermediate signal is seen in the more medial normal superior longitudinal fasciculi in (Figure 22B).

Figure 23 is a higher slice in the same case as in Figure 22 where a T2-wSE image is compared with a narrow mD dSIR image. No abnormality is seen on the T2-wSE image (Figure 23A) but a focal lesion is seen on the dSIR image (long thin arrow) (Figure 23B). The corticospinal tracts are also seen (short thin arrows). There are areas of increased signal in most of the white matter in (Figure 23B) (thick arrows). Only about 5–10% of the white matter has a low signal (dark) and appears normal. High signal boundaries are seen between white and gray matter.

In Figure 22 most of the normal appearing white matter on the T2-wSE image (Figure 22A) shows as normal tissue with a dark (low) signal appearance in Figure 22B (thick arrows). In Figure 23, most of the normal appearing white matter in Figure 23A shows abnormal high signal in Figure 23B (thick arrows). Even in retrospect it is not possible to decide whether the normal appearing white matter in Figures 22A,23B will appear normal or abnormal on the corresponding narrow mD dSIR images.

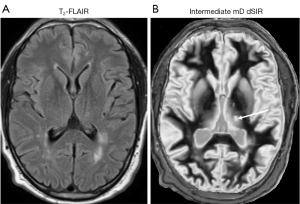

In another case of MS, no abnormality is seen on the T2-FLAIR image (Figure 24A) in the thalamus, but a focal lesion is seen in the thalamus using an intermediate mD dSIR sequence (thin white arrow) (Figure 24B). The intermediate mD dSIR sequence is targeted to null white matter and produce positive contrast from increases in T1 over a broader domain than in Figures 22B,23B. Figure 24B which used an intermediate mD shows less lesion contrast in white matter than Figures 22B,23B which used narrow mDs.

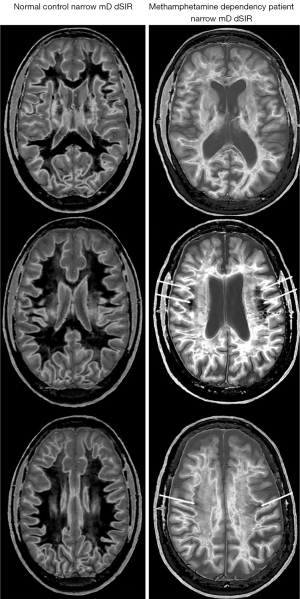

Figure 25 shows narrow mD dSIR images in a normal, gender, ethnicity and socio-economically matched 49-year-old control (left column), and a 51-year-old patient with methamphetamine dependency for 20 years followed by an abstinence period of 120 days (right column). In the control images, most white matter appears normal with a low signal (dark) (left column), but in the patient most white matter appears abnormal with a high signal (light) (right column). There is only a small amount of normal white matter (dark) present on the patient’s images (thin white arrows, right column).

In the normal control, there is contrast between more peripheral normal white matter (dark) (left column) and more central normal white matter of the superior longitudinal fasciculi (mid-gray).

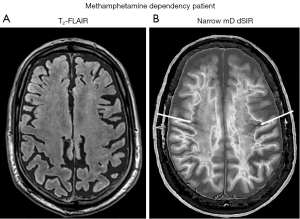

Figure 26 compares a T2-FLAIR image (Figure 26A) with a narrow mD dSIR image (Figure 26B) in the 51-year-old patient. No abnormality is seen on the T2-FLAIR image (i.e., it shows normal appearing white matter) but extensive high signal abnormalities are seen in white matter on the narrow mD dSIR image. There are only small areas of normal low signal (dark) white matter on this image (thin arrows).

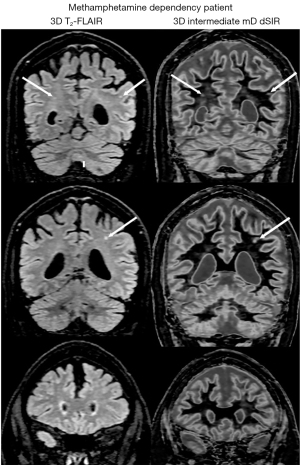

Figure 27 shows comparison of 3D T2-FLAIR images (left column) and 3D intermediate mD dSIR images (right column) in another patient with methamphetamine dependency. Focal lesions are seen in white matter on both the T2-FLAIR and intermediate mD dSIR images (thin arrows). The intermediate mD dSIR images are less sensitive to change in white matter than the narrow mD dSIR images shown in Figure 25 (right column) and Figure 26B. The comparison illustrates the benefits of using a narrow mD to achieve high lesion contrast compared with using an intermediate mD where the lesion contrast is lower and about the same as that seen on the T2-FLAIR image.

Discussion

The use of dSIR and drSIR sequences described in this paper follows directly from the CCT. Increased sequence weighting (higher slope of the T1-bipolar filter in the mD) is used to compensate for the small change in T1 (ΔT1) which may be present in normal appearing tissues but be insufficient to produce contrast with the lower slope T1-bipolar filters of conventional sequences. The region of the T1-bipolar filter which has the steepest slope is the mD, and this needs to be narrow for high contrast amplification. This is not a problem when the objective is to image small changes in T1 which can easily be accommodated within a narrow mD. Detection of small changes in T1 in normal appearing tissues is therefore a very appropriate application for targeted narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences.

Targeting

All MRI examination are targeted to a lesser or greater extent. Even whole-body MRI includes sequences sensitive to only a few TPs (Table 5). The term tMRI is usually applied to sequences focused on specific tissues, their TPs and changes in these TPs in disease (e.g., #4–7 in Table 5). This is greater targeting than that of typical conventional T1-wSE and IR sequences in which there is sensitivity to changes in T1 over a relatively broad T1 domain as shown by the slopes of their filters. They typically have a maximum slope centrally but lesser slopes extending out on either side to flat plateaus at low and high values of T1 where there is less sensitivity to changes in T1 (Figures 3,6). Narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences are highly sensitive to small changes in T1 in the mD (Figures 9,11). dSIR and drSIR sequences are generally less sensitive to changes in T1 outside of the mD. Larger changes in T1 in the domains outside of the mD can usually be shown with conventional sequences.

Table 5

| # | Target |

|---|---|

| 1 | Whole body |

| 2 | Region e.g., head, thorax |

| 3 | Organ or physiological system e.g., brain, CNS |

| 4 | Tissue or tissue components e.g., white matter, myelin water, short T2 components |

| 5 | Tissue or tissue component property e.g., T1, T2 |

| 6 | Sign of change in tissue property |

| 7 | Size of change in tissue property |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CNS, central nervous system.

dSIR and drSIR T1-bipolar filters

The dSIR and drSIR T1-bipolar filters provide keys to understanding the targeting, signal, contrast, boundaries, T1 mapping and GBCA enhancement seen on the dSIR and drSIR images. dSIR and drSIR T1-bipolar filters are univariate for T1 (i.e., dependent on T1 but not on ρm or T2) and are comprehensive i.e., only a T1 TP-filter is needed to interpret dSIR and drSIR images unlike, for example, SE and T2-FLAIR images where three different TP-filters (ρm, T1, and T2) are needed to understand them.

As the magnitude of ΔTI and the matched change in T1 ΔT1 become smaller, the small change approximation of differential calculus used in the CCT, and the linear approximation used for T1 mapping both become more accurate. Ultimately, however, the images become signal and/or contrast limited. In addition, as the changes between serial examinations become smaller, rigid body registration becomes more accurate.

Normal tissues

The normal tissues and fluids of primary interest are white matter, cortical gray matter, central gray matter and CSF. Normal white matter may be subdivided into 20 or more categories (26), and cortical gray matter into 4–6 categories. Central gray matter includes many nuclei with varying degrees of organic iron associated with them. The iron shortens T1 and T2 but to a first approximation, only the T1 shortening is relevant with dSIR and drSIR sequences.

It is very helpful to know the T1s of normal tissues. Since dSIR and drSIR images are T1 maps and their signals in the mD can be linearly scaled to be T1 values. The order of tissue signal or brightness directly follows from their T1 values. Even if the nulling TI is not exact, the order of tissues in the mD (apart from those near the null point) is usually well preserved. Nulling of white matter can be targeted at the shortest T1 of the relevant normal white matter tissues.

Identification of normal white matter is based on anatomical location, signal in relation to other normal white matter, symmetry, and studies of normal subjects of the same age with the same technique.

The cortex may be more easily visualized with the drSIR sequence for increases in T1. This makes the boundary between cortex and CSF low signal. Increases in T1 produce negative contrast in this situation.

Normal appearing tissues

The usual approach to imaging normal appearing tissues such as white and gray matter seen with T1- and T2-weighted conventional sequences is to use TPs other than T1 and T2 such as magnetization transfer and diffusion, or metabolites using MR spectroscopy. In this paper, the approach to imaging normal appearing white and gray matter is different. A TP (T1) used with conventional sequences is employed. Small changes in T1 not seen using conventional T1-weighted IR sequences are then targeted with dSIR and drSIR sequences.

Contrast

The most prominent feature of dSIR and drSIR images is their high soft tissue contrast. This may be much greater than that seen with conventional highly T1-weighted IR sequences such as MP-RAGE. White matter nulled IR sequences of this type are often used to maximize contrast as in the determining anatomy in the thalamus (27), but much higher contrast is available with dSIR and drSIR sequences.

Boundaries

The high signal, often high contrast boundaries of dSIR and drSIR are a characteristic feature of these images. Boundary creation of this type can, in principle, be applied to any pair of tissues with different T1s, subject to noise and/or artefact limitations when the difference in T1 between the tissue is small and the magnitude of the corresponding ΔTI is small. The objective is to obtain maximum signal from a partial volume affected voxel with a T1 between those of the two tissues of interest. The approach can be applied to normal tissues to define anatomy, and to normal and abnormal tissues to define lesion boundaries. The sharply defined boundaries of the dSIR and drSIR inages may create the impression that they are of higher spatial resolution than comparable T2-wSE and T2-FLAIR images.

dSIR and drSIR images as T1 maps

Within the mD it is possible to use a linear approximation to produce T1 maps. The function becomes more linear as the ΔTI and mD are reduced (see Figure 14A with a narrow mD and compared with Figure 14B with a wide mD).

In comparison with conventional multi-TI T1 mapping, dSIR and drSIR images/T1 maps:

- require no additional acquisition;

- are usually higher spatial resolution than the multiple TI acquisitions used with conventional T1 mapping;

- are targeted at the T1s of interest in the mD rather than the whole range of T1s seen on the image and have a narrower range of maximum and minimum values. Rather than values for very long T1 CSF and short T1 tissues providing the upper and lower limits of the display gray-scale range as with conventional T1 maps, dSIR and drSIR images use the same gray-scale for a smaller range of T1 values and so have higher contrast resolution (i.e., change in the gray scale for the same change in T1);

- may have reduced partial volume effects because of attenuation of signals towards zero in tissues and fluids outside the mD;

- utilize the analytic solutions in

Eqs. [24, 25]. These provide an alternative to the fitting procedures used in conventional T1 mapping.

GBCA enhancement

- GBCA enhancement may be seen in normal tissue (e.g., white matter) where the initial TI is the same for other studies as well as in abnormal tissues (typically with an increase in T1) where the initial nulling TI needs to be increased so that the lesion is nulled pre-enhancement and positive contrast can be seen with the reduction in T1 post contrast using a drSIR sequence;

- The blood brain barrier plays a critical role in disease detection where disruption results in increased GBCA concentration;

- 3D isotropic acquisition with rigid body registration is usually necessary to obtain subtracted images that are not artefacted because of the different locations of pre and post images in the subject;

- Post minus pre GBCA subtractions can be targeted at (a) enhanced lesion contrast by using different TIs, and (b) specific identification of GBCA effects using the same TI;

- Quantitation of T1 change on drSIR images can be directly related to GBCA concentration.

Serial studies

The situations that arise in serial examinations include those seen with tumors and other lesions where there may be changes in T1 but also changes in site, size, shape, surface etc. which is manifest as differences at lesion boundaries.

The primary interest with dSIR and drSIR images is not in large changes between examinations, which are usually obvious with conventional sequences, but small changes in T1 and/or the spatial features of tissues. In this situation, rigid body registration may allow accurate registration and recognition of boundaries.

Changes in T1 may affect the location of boundaries without change in space. Detailed studies may be necessary to determine whether or not this is a significant confounding factor, and how to deal with it.

Quantitation

This exploits the direct measurement of T1 and the high contrast boundaries produced by dSIR and drSIR sequences. Radiomics and artificial intelligence may benefit from the clarity and analytic form of dSIR and drSIR images.

Cancellation lines

With magnitude reconstructed IR sequences, cancellation lines arise in voxels with mixed tissues where the positive Mz from shorter T1 tissues is balanced by the negative Mz from longer T1 tissues so there is no net Mz and therefore no signal after the 90° pulse. Within the brain, when nulling white matter, there is no shorter T1 tissue present with a positive Mz and so all tissues and fluids including gray matter and CSF have zero or negative Mzs and there is no cancellation line. When using a TI longer than that needed to null white matter, but shorter than that needed to null gray matter, there are voxels with mixtures of white matter (positive Mz) and gray matter (negative Mz). When the proportions balance in mixed tissue voxels there is no net Mz and a cancellation line arises at the boundary between white and gray matter. As TI is increased this occurs up until the TI necessary to null gray matter after which, with further increases in TI, both white and gray matter have positive Mzs. However, voxels with a mixture of white or gray matter and CSF may show positive Mz for one or both of these tissues, and negative Mz for CSF, leading to net zero Mz in voxels at the boundaries between them and CSF so cancellation lines occur at the junction between white or gray matter and CSF.

The subtraction: TIs image (nulling white matter) minus TIi image (nulling a T1 between white and gray matter), and subsequent division with the dSIR sequence has the cancellation line with zero signal (0) on the longer TI image turned into a high signal (+1) boundary between white and cortical gray matter in voxels with a mixture of white and cortical gray matter just inside cortical gray matter (e.g., Figure 15).

The subtraction: TIs image (nulling white matter) minus long TI image (nulling a T1 between those of cortical gray matter and CSF) and subsequent division with the dSIR image leads to the cancellation line between cortical gray matter and CSF on the longer TI image becoming a high signal boundary in voxels with a mixture of cortical gray matter and CSF just outside the brain (e.g., Figure 16).

This also applies to lesions which have longer T1s than the nulling T1 of the second TI sequence. This results in high signal boundaries between normal and abnormal tissue around the lesion with a lower signal within this boundary inside the lesion.

The same general approach applies to the dSIR sequence. The section on contrast at tissue boundaries in this paper provides the mathematical formalism for understanding the contributions to contrast in this situation using T1-filters, changes in tissue f with T1 and changes in f with distance (x).

Technical features

- The sequences used to create dSIR and drSIR images (2D IR FSE and 3D IR GE) are widely available on standard MRI systems and usually require no special implementation. The sequences require adjustment of their TIs to correspond to the increases in tissues T1s with increasing B0. The coding required to add, subtract and divide IR images can written in MATLAB or other similar packages. Rigid body registration packages are widely available e.g., in FSL (fMRIB software library);

- dSIR and drSIR sequences can benefit from interleaving the two different TI acquisitions in a single sequence;

- There are also likely to be benefits in scan time from the use of sense, compressed sense and artificial intelligence;

- Ultra low field imaging e.g., at 0.064T may be feasible with adaption to the short T1s of white matter and gray matter (275 and 330 ms, respectively, in adults) (28);

- Denoising either independently or combined with deep learning may be a significant benefit.

Synthetic dSIR and drSIR images

From Eq. [14] and Figures 9,12, it is possible to calculate synthetic dSIR and drSIR images from T1 maps produced from other sources such as MP2RAGE, MR fingerprinting and actual flip angle-ultrashort TE (UTE) (29). These provide flexibility for targeting and generating contrast using different TIs.

It is also possible to make narrower mD synthetic dSIR and drSIR images from wider mD dSIR and drSIR images. This can provide a series of progressively smaller magnitude ΔTI images to optimize contrast for different ΔT1s within the mD of the wider dSIR or drSIR image.

Comparison with other sequences

The DIR sequence has partially opposed but net positive T1-weighting as well as positive T2-weighting so that for increases in T1 and T2 positive synergistic contrast results.

Clinical comparisons of dSIR and drSIR sequences are usually made with MP-RAGE, T2-wSE (both with a single use of T2) and/or T2-FLAIR sequences. The latter has opposed T1 and T2 contrast but with increased T2-weighting due to the use of a longer TE than the conventional T2-wSE sequences. As a general rule, non-synergistic (e.g., single use of a TP) and opposed contrast sequences do not show contrast due to small changes in T1 in lesions as well as specifically targeted highly synergistic sequences such as narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences.

The FLAWS (18,19) sequence began as separate white matter nulled and CSF nulled IR images. Later developments included division by a single image as the FLAWS division (FLAWS-div) sequence, and division of two subtracted images by the sum of them as the FLAWS-hc and FLAWS-hco images. They are similar to dSIR and drSIR sequences but use wide mDs and are sensitive to changes in T1 over a broad T1 domain. They also use two fixed widely spaced TIs. Unlike narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences, they are not targeted at small changes in T1 in specific tissues. The wide mDs of the FLAWS-hc and FLAWS-hco sequences mean that they generally show lower contrast than that seen in the mD of narrow mD dSIR and drSIR sequences. The FLAWS-hc and FLAWS-hco sequences do not have T1-bipolar filters. Their T1-filters are essentially monotonic (Figure 1) (19). Also, they do not show high signal white matter gray matter boundaries as seen with narrow and intermediate mD dSIR and drSIR sequences.

Tissue targets

Emphasis has been placed on normal white or gray matter as the baseline, reference or nulled tissue. Within gray matter there are specific targets of importance including cortical gray matter and central gray matter nuclei. There are also mixed white and gray matter structures such as the hippocampus, thalamus, brainstem and striate cortex. The T1 values of central gray matter tissues extend from shorter than white matter for the globus pallidus to about that of cortical gray matter. It is possible to use a wide mD to cover all gray matter to ascertain T1s for nulling purposes. It is then possible to focus on specific targets within central gray matter using specific nulling TIs. Disease of central gray matter can result in increases or decreases in T1.

The complex anatomy and small size of some gray matter nuclei and mixed white and gray matter structures favor the use of thin slice isotropic 3D acquisitions.