Emergency CT of blunt abdominal trauma: experience from a large urban hospital in Southern China

Abdominal injuries have contributed to a large number of trauma-related death, which is the leading cause for men and women under the age of 45 years in the United States (1). Imaging examinations are often required, because clinical examinations are often unreliable and unspecific in patients with blunt abdominal trauma. In patients with blunt abdominal trauma, both solid and hollow viscera may be injured. These injuries may result in persistent bleeding or peritonitis, which might be lethal. For some injuries, if correct diagnosis is obtained and proper therapeutic strategies are carried out in time, the patients will recover without sequelae, otherwise morbidity and mortality may increase. Therefore, prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical. Emergency CT plays an important role in treatment decision-making. With the installation of CT scanners in the emergency room or trauma unite, immediate accessible of CT examination has decreased the usage of diagnostic peritoneal lavage and increased the success of conservative nonsurgical treatment. Knowledge of CT manifestations of viscera injuries can facilitate accurate interpretation and clear communication between radiologists and the referring physicians. In our hospital, a 2,000-bed general urban hospital, a 16-slice CT scanner was installed in the emergency unit to provide 7×24 hours service. In the present pictorial review, CT findings of viscera injuries in patients with blunt abdominal trauma are described.

CT protocol

In our hospital, if the patient’s hemodynamic status can sustain, CT is the first line imaging modality to look for or exclude viscera injuries. According to prompt and simple rules, scanning from lung base to symphysis pubis without any oral and intravenous contrast materials is routinely performed at a 16-slice CT scanner. A collimation of 1.5 mm and a pitch of 1.188 is used with a kilovoltage of 120 kVp and auto-modulated current. 2-mm axial sections with a gap of 1 mm are reconstructed at first. Axial, coronal and sagittal reformatted images are obtained at a contiguous 5-mm section. All the images are transported to picture archive and communication system (PACS).

Although intravenous contrast materials are not routinely used in our hospital, we keep a flexible protocol to be tailored according to the need of individual patient. The alternation of scanning protocol is decided by the on-duty radiologist according to the initial scanning. If necessary, a bolus of intravenous contrast materials is injected at a rate of 3–5 mL/sec with a dose of 100 mL and chased by 20 mL of saline solution. A single phase scanning at a delay of 60 sec from the beginning of injection is acquired to achieve enhancement of most solid organs. If major vascular injuries are suspected, arterial phase will be obtained using auto-trace-trigger. A delay scanning will be performed at 120–180 sec if the urinary tract injuries are suspected. If equivocal findings of bowel injuries are detected or patients’ clinical condition deteriorate and bowel injuries are suspected, oral contrast materials should be administrated at a repeat CT examination. CT angiography protocol will be used for patients with suspected vascular injuries.

CT findings of common blunt abdominal trauma

Hemoperitoneum

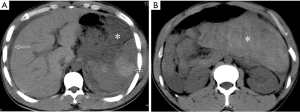

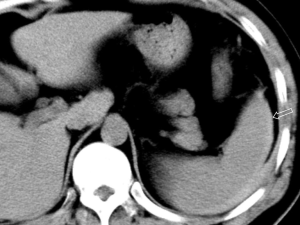

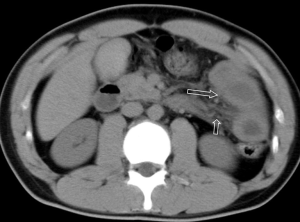

At trauma, three kinds of blunt force can impact on abdomen to result in viscera injuries. The three mechanism forces are deceleration, external compression and crushing (2). These forces impact on solid or hollow organs and can cause laceration of solid organs, tear at vascular pedicles and mesenteric attachments, and burst of hollow viscera. All these injuries may lead to bleeding. If the bleeding restricts intra-organ or a space, it may manifest a hematoma (Figure 1). In most situations, non-clotted blood often flows into peritoneal cavity, hemorrhagic peritoneal fluid can be seen. Initially, the hemorrhage tends to accumulate in gravity depended recesses (Figure 2). If the bleeding persists, blood will fill the peritoneal cavity completely. Therefore, hemoperitoneum is the most common CT finding of viscera injuries in patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Radiologists should look for hemorrhage at anatomic recesses at first. Focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) has been used to address hemoperitoneum in real time (3). Hemorrhage shows higher density than conventional free peritoneal fluid with a CT value of 30–45 HU. Sometimes, blood adjacent to the bleeding site may be clotted to form hyper-attenuation hematoma, which is known as sentinel clot (Figure 3) (4).

Solid viscera injuries

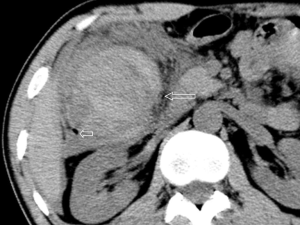

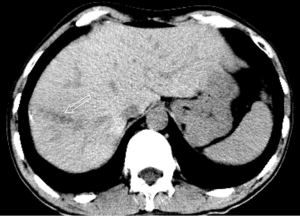

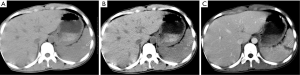

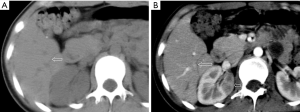

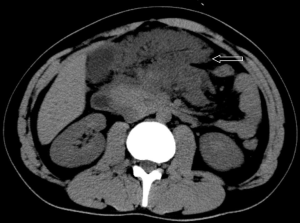

The crushing or shearing force at blunt abdominal trauma due to knocking into abdominal walls or rapid deceleration can break the solid organs. Spleen is the most commonly involved organ at blunt abdominal trauma, followed by liver, kidney and pancreas. Lacerations often appear as linear or focal low attenuation across the parenchyma (Figures 4,5). The involvement of large vessels can result in obvious bleeding. If the laceration is focalized within the capsular, hematoma within the organ or subcapsular may be seen (Figures 6,7). Sometimes, hematoma might be subtle, narrow window width setting can be helpful to visualize it (Figure 8). Occasionally laceration may be subtle and might be missed at unenhanced CT. For these cases, contrast enhanced CT is often indicated to confirm or exclude the injuries at in our hospital (Figure 9).

Pancreatic injuries often occur at the neck and body for crushing on the vertebral body, which may result in fracture of pancreas. The injuries may appear as hypoattenuation stripe or an area superficial to or extending across the pancreas, or focal enlargement of pancreas (Figure 10). If the pancreatic duct is involved, morbidity and mortality will increase due to the infected pseudocyst, abscess, fistulate, or sepsis. Laceration of more than 50% of the pancreatic thickness increases the likelihood of pancreatic duct injury. MR cholangiopancreatography can facilitate the diagnosis of duct involvement. Contrast enhanced CT is helpful in visualizing the pancreatic injuries, but the pancreas may appear normal within the first 12 hours after the initiation of trauma (5). Therefore, repeat CT within 24–48 hours later is recommended in patients with suspected pancreas injuries, especially in those with mid-upper abdomen blows and complain of epigastric or diffuse abdominal pain and vomiting (6). Several indirect signs, such as fluid in the peripancreatic fat or in the plane separating the pancreas from the splenic vein and thickening of the left anterior renal fascia, may imply the pancreatic injuries.

Hollow viscera and mesenteric injuries

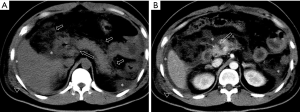

Hollow viscera and mesenteric injuries are rare, occur only in approximately 5% of patients with severe blunt abdominal trauma (7). The leak of bowel content may result in peritonitis and sepsis. Delay diagnosis often results in substantial negative consequences, such as prolonged hospital stays, increased morbidity and mortality. Surgical managements are often required to control the damage (8). Therefore, diagnostic radiologists should bear in mind to look for subtle CT signs of bowel and mesenteric injuries in every patient with blunt abdominal trauma. These signs include bowel wall transaction discontinuity, extraluminal air, focal bowel wall thickening, free peritoneal fluid, mesenteric infiltration or hematoma (Figures 11-14) (9). Unfortunately, these signs have low sensitivity or specificity.

Bowel injuries remain a diagnostic challenge for radiologists. Contrast enhanced CT may show abnormal bowel wall enhancement, but its sensitivity is only 10–15% (1). Oral contrast materials administration can demonstrate leak of oral contrast materials with a specificity of 100%, but its sensitivity is only 8–10% (1). Routine administration of oral contrast materials in patients with blunt abdominal trauma remains controversial. A meta-analysis shows that there was no difference in detecting bowel injuries with or without oral administration of contrast materials (10). When multiple solid-organ injuries were found, the incidence of bowel injury increases substantially. One report describes that if three abdominal solid organs were injured, the risk for bowel injury is 34% (11). Pancreatic injuries associated duodenal injuries in approximately 20% of cases (12). Thus, when there are multiple solid-organ injuries or pancreatic injuries, radiologists should look for signs of bowel injuries carefully.

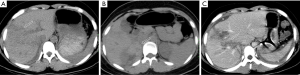

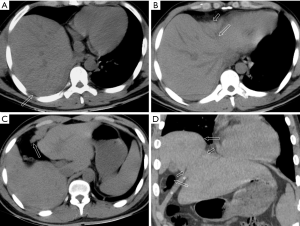

Diaphragmatic injuries

A sudden increase of intra-abdominal pressure in blunt trauma can result in diaphragmatic injuries. Herniation of abdominal organs into thorax can occur immediately or delayed. CT can reveal diaphragmatic discontinuity and herniation of abdominal organs into thorax (13). The herniated organs often drop to posterior chest wall. This sign is called “dependent viscera sign” (Figure 15A). Herniated abdominal contents through the diaphragmatic rent form a waist-like constriction, which is termed as “collar sign” (Figure 15B). Sometimes, diaphragmatic discontinuity can be revolved directly (Figure 15C). Multiplanar reformation of CT images can facilitate depiction of these signs (Figure 15D).

Conclusions

Emergency CT plays an important role in the management of blunt abdominal trauma. Although contrast enhanced CT can facilitate depicting both solid and hollow viscera injuries, unenhanced CT can detect severe injuries effectively. As most solid organ injuries can be treated successfully by nonsurgical conservation therapeutic stratagem, unenhanced emergency CT scanning is cost-effective in managing the blunt abdominal trauma. In order to reduce the radiation dose and contrast-induced nephropathy, and improve efficiency, contrast enhanced CT should be reserved as an alternative protocol for patients in need. Oral contrast materials are also administrated to confirm questionable findings of bowel injuries. Recently, FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma) has been introduced, which may alternate the work flow of blunt abdominal trauma. Perhaps, after FAST screening, most patients with blunt abdominal trauma do not need to undergo CT examination, while contrast enhanced-CT with tailored protocol may be indicated in a small portion of patients for special purpose.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Soto JA, Anderson SW. Multidetector CT of blunt abdominal trauma. Radiology 2012;265:678-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hughes TM, Elton C. The pathophysiology and management of bowel and mesenteric injuries due to blunt trauma. Injury 2002;33:295-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richards JR, McGahan JP. Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) in 2017: What Radiologists Can Learn. Radiology 2017;283:30-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Orwig D, Federle MP. Localized clotted blood as evidence of visceral trauma on CT: the sentinel clot sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1989;153:747-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong YC, Wang LJ, Lin BC, Chen CJ, Lim KE, Chen RJ. CT grading of blunt pancreatic injuries: prediction of ductal disruption and surgical correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1997;21:246-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gupta A, Stuhlfaut JW, Fleming KW, Lucey BC, Soto JA. Blunt trauma of the pancreas and biliary tract: a multimodality imaging approach to diagnosis. Radiographics 2004;24:1381-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buck GC 3rd, Dalton ML, Neely WA. Diagnostic laparotomy for abdominal trauma. A university hospital experience. Am Surg 1986;52:41-3. [PubMed]

- Pommerening MJ, DuBose JJ, Zielinski MD, Phelan HA, Scalea TM, Inaba K, Velmahos GC, Whelan JF, Wade CE, Holcomb JB, Cotton BA. AAST Open Abdomen Study Group. Time to first take-back operation predicts successful primary fascial closure in patients undergoing damage control laparotomy. Surgery 2014;156:431-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bates DD, Wasserman M, Malek A, Gorantla V, Anderson SW, Soto JA, LeBedis CA. Multidetector CT of Surgically Proven Blunt Bowel and Mesenteric Injury. Radiographics 2017;37:613-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee CH, Haaland B, Earnest A, Tan CH. Use of positive oral contrast agents in abdominopelvic computed tomography for blunt abdominal injury: meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur Radiol 2013;23:2513-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nance ML, Peden GW, Shapiro MB, Kauder DR, Rotondo MF, Schwab CW. Solid viscus injury predicts major hollow viscus injury in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 1997;43:618-22; discussion 622-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Linsenmaier U, Wirth S, Reiser M, Körner M. Diagnosis and classification of pancreatic and duodenal injuries in emergency radiology. Radiographics 2008;28:1591-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gong J, Qiao K, Wang Z, Xu J. Demonstration of an inconspicuous right diaphragmatic hernia in a blunt trauma patient using CT multi-planar reformation. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2011;1:44-5. [PubMed]