Severe parapharyngeal-mediastinal emphysema triggered by Guilinggao

Introduction

Parapharyngeal-mediastinal emphysema (PME) is a rare condition that typically manifests as chest tightness, pain, and subcutaneous emphysema. Due to its nonspecific symptoms, it is frequently misdiagnosed or overlooked. Most cases are benign and self-limiting, with small air pockets resolving spontaneously or with minimal supportive care, suggesting its true incidence is likely underreported.

Severe PME, however, can cause life-threatening complications such as pneumopericardium, tension pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, or venous air embolism, requiring invasive treatment (1). Common causes include spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM)—triggered by intense coughing, vomiting (2), or exertion—and secondary pneumomediastinum from trauma, medical interventions, or rare conditions like Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndromes.

Eating-induced PME is particularly rare, often mild, and easily missed. Hard food ingestion has been documented as a cause, but PME from soft food remains unreported, underscoring the need for greater awareness and careful diagnosis in such cases.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old male presented to the emergency department 30 minutes after experiencing diffuse, dull pain in the central chest. The discomfort had begun shortly after the rapid ingestion of Guilinggao. The chest pain was not severe but was accompanied by a sensation of tightness, mild shortness of breath, and general discomfort. The patient denied having a cough, throat pain, severe chest pain, significant difficulty breathing, fever, or chills. He also had no history of vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or prior concerns suggestive of a Mallory-Weiss tear or similar conditions.

On admission, his vital signs were stable, with a temperature of 36.5 ℃, pulse of 87 bpm, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure of 121/86 mmHg, and a weight of 75 kg. Physical examination revealed no external abnormalities in chest shape, with symmetric breast structure and no tenderness over the sternum. The respiratory system assessment showed normal chest movement and rhythm without intercostal abnormalities. Vocal fremitus was normal, and percussion revealed clear resonance bilaterally. Lung borders were within normal limits, but breath sounds were slightly reduced on the left side. No wheezes, crackles, pleural rubs, or subcutaneous crepitus were detected. Cardiovascular examination showed no precordial bulge or thrills, with the apex beat localized to the 5th intercostal space 1 cm medial to the left midclavicular line. Heart rate was regular, and no murmurs or extra sounds were auscultated. Blood oxygen saturation was 100%.

Diagnostic studies

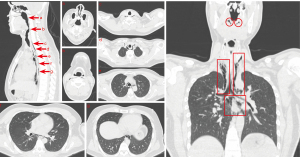

A computed tomography (CT) scan performed on the day of admission revealed extensive emphysema in the oropharynx, neck, and mediastinum. Air was noted to extend along the esophageal spaces without significant displacement of mediastinal structures. No radiopaque foreign bodies were identified within the esophagus (Figure 1).

Treatment

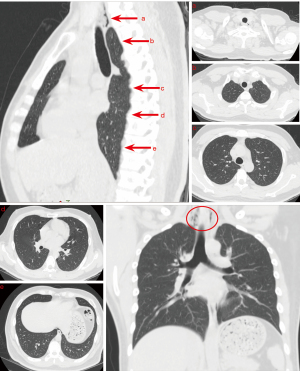

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory medications. He was also instructed to remain nil by mouth to aid in mucosal healing, and this was strictly implemented during his treatment. His symptoms improved significantly over several days, with follow-up imaging demonstrating radiological evidence of air resorption (Figure 2).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged with a set of recommendations to facilitate recovery and prevent recurrence. He was advised to maintain adequate rest with 6–8 hours of sleep daily, balance work and rest, engage in moderate physical activity such as walking or Tai Chi, avoid overexertion, and strive for emotional stability. Follow-up chest X-rays confirmed the progressive resolution of emphysema, and the patient remained asymptomatic.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Mediastinal emphysema is the accumulation of air within the mediastinum, often with subcutaneous emphysema (3,4). Though rare and typically benign, it may require intervention if complications arise (5). Causes include spontaneous events, trauma, iatrogenic injuries, gastrointestinal perforations, or infections (6). The annual incidence of SPM is estimated to range from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 45,000 (2,3,7), but rates are higher (1–12%) in cases involving thoracic trauma or procedures. Notably, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) increased

mediastinal emphysema incidence sixfold (8). When air spreads into the parapharyngeal space. Although rare, PME can lead to severe complications such as mediastinitis, which has a high mortality rate (9,10). Most cases are mild and self-limiting, often going undiagnosed, especially when symptoms are nonspecific or overlap with other conditions (11-13). Symptoms such as neck or chest pain, dysphagia, and dyspnea may mimic other disorders, complicating diagnosis and increasing the risk of misdiagnosis (14).

In some cases, patients are asymptomatic in the early stages, with significant signs such as fever or mediastinitis only appearing upon disease progression or secondary infection. Severe pneumomediastinum can lead to worsening chest pain, respiratory distress, fever, and in extreme cases, life-threatening complications such as airway obstruction or mediastinitis. However, in our case, the patient remained stable throughout the clinical course, with no signs of severe progression. Misdiagnoses are common, highlighting the need to enhance awareness of PME’s signs and symptoms, particularly in easily overlooked scenarios like soft food-induced PME, to improve diagnostic accuracy among healthcare providers.

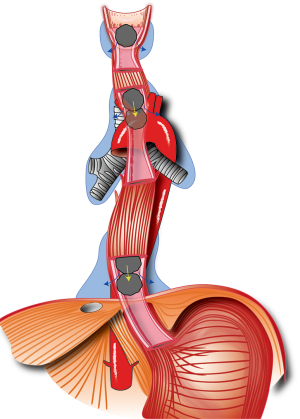

Food-induced PME is uncommon, with hard or sharp foods like bones being the main cause due to esophageal perforation (15-17). However, soft foods, like Guilinggao, can also cause microtears in the pharyngeal or esophageal mucosa through rapid swallowing or mechanical pressure, allowing air to enter the mediastinum. Severe coughing triggered by food ingestion may further exacerbate this condition via the Macklin effect (18). When soft foods like Guilinggao are swallowed quickly and in large bites, the rapid descent of the food, combined with strong negative esophageal pressure, can lead to mucosal tears. This injury, coupled with the mechanical compressive force exerted by the food, may permit air to enter the mediastinum through the damaged mucosa. The food itself may act as a “pump”, propelling air into adjacent spaces and potentially extending the emphysema.

Although the potential mechanism remains speculative, our case highlights the importance of considering PME in patients who present with chest or neck pain after ingesting food, even when the food is soft. This report aims to raise awareness of PME as a potential diagnosis in similar cases. In our patient, the emphysema spread to the parapharyngeal space of the nasopharynx (Figure 3), underscoring the importance of early recognition and appropriate management.

It is important to note that in cases where the lesion is located lower in the esophagus, a dual contrast study with oral contrast would be more appropriate to provide a detailed evaluation of the esophageal mucosa. In our case, since the lesion was identified in the oropharyngeal and mediastinal regions, CT imaging was sufficient for diagnosing the emphysema.

Healthcare providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for PME in patients presenting with chest or mediastinal pain following food ingestion, even when the food is soft. Recognizing atypical presentations and rare causes is crucial for prompt diagnosis and effective management.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Funding: The work was funded by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-2024-2902/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Selvanayagam LS, Pallewatte AS, Sivansuthan S. Spontaneous Subcutaneous Emphysema in a Teenage Male Extending As Pneumomediastinum, Pneumothorax, Pneumopericardium, and Epidural Pneumatosis: A Rare Combination of Anatomical Locations. Cureus 2023;15:e43462. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, Kojima E, Shizu M, Okachi S, Ninomiya K, Morioka H. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: an algorithm for diagnosis and management. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2009;3:301-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, Morera R, Escobar I, Saumench J, Perna V, Rivas F. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:1110-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kouritas VK, Papagiannopoulos K, Lazaridis G, Baka S, Mpoukovinas I, Karavasilis V, Lampaki S, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Papaiwannou A, Karavergou A, Kipourou M, Lada M, Organtzis J, Katsikogiannis N, Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis K, Zarogoulidis P. Pneumomediastinum. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:S44-9. [PubMed]

- Grewal J, Gillaspie EA. Pneumomediastinum. Thorac Surg Clin 2024;34:309-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Işık NI, Kurtoglu Celık G, Işık B. Evaluating emergency department visits for spontaneous and traumatic pneumomediastinum: a retrospective analysis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2024;30:107-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newcomb AE, Clarke CP. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a benign curiosity or a significant problem? Chest 2005;128:3298-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reis AE, Emami N, Chand S, Ogundipe F, Belkin DL, Ye K, Keene AB, Levsky JM. Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Outcomes of Pneumomediastinum in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Case-Control Study. J Intensive Care Med 2022;37:12-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- St Clair TM, Zwemer E. Diffuse Subcutaneous Emphysema. N Engl J Med 2019;380:e20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AISNER M. FRANCO JE. Mediastinal emphysema. N Engl J Med 1949;241:818-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsiao YT, Lin SW, Chuang PW, Tsai MJ. Pneumomediastinum, Pneumoretroperitoneum, Pneumoperitoneum and Subcutaneous Emphysema Secondary to a Penetrating Anal Injury. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:707. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goh BK, Ng KK, Hoe MN. Traumatic epidural emphysema. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:E528-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koletsis E, Prokakis C, Baltayiannis N, Apostolakis E, Chatzimichalis A, Dougenis D. Surgical decision making in tracheobronchial injuries on the basis of clinical evidences and the injury's anatomical setting: a retrospective analysis. Injury 2012;43:1437-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen IC, Tseng CM, Hsu JH, Wu JR, Dai ZK. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in adolescents and children. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2010;26:84-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iida T, Nakagaki S, Satoh S, Shimizu H, Kaneto H. Image of the month: Severe Mediastinitis and Pneumomediastinum Following Esophageal Perforation by a Fish Bone. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1262. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeh CM, Ho WJ, Hsieh CC. Pneumomediastinum and neck emphysema in a women after eating chicken bone. Asian J Surg 2023;46:2742-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chew FY, Yang ST. Boerhaave syndrome. CMAJ 2021;193:E1499. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marsico S, Del Carpio Bellido LA, Zuccarino F. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum and Macklin Effect in COVID-19 Patients. Arch Bronconeumol 2021;57:67. [Crossref] [PubMed]