A case presentation of pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung presenting as a small nodule with early cavitary change and rapid progression

Introduction

Pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung, a rare non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) subtype, has a low incidence of 0.1–0.4% according to the literature (1). It primarily affects male smokers over 60 years and is characterized by its rapid progression and poor prognosis (2-5). Previously described cases usually show pleomorphic carcinoma as a large peripheral mass with central low attenuation, often displaying cavitary changes in larger lesions (6,7). This report details a unique case of a small peripheral nodule with early cavitary change and rapid progression following surgery, accompanied by a literature review.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old male was referred to Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital after detection of a left upper lobe (LUL) nodule in a low-dose chest computed tomography (CT) scan performed as part of a national lung cancer screening program. He had a 15-pack-year smoking history and had ceased smoking two years prior. The patient had previously undergone transurethral resection for bladder cancer two years earlier, with no recurrence noted since then. He presented with mild cough and sputum but no other significant symptoms.

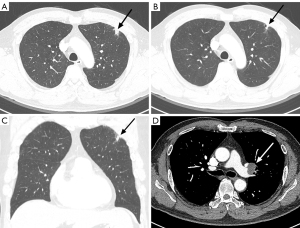

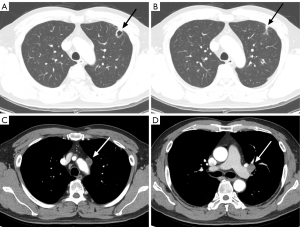

Contrast-enhanced chest CT showed a small nodular lesion approximately 1.3 cm in diameter in the subpleural area of the LUL on the lung window setting, with no significant change compared to lung cancer screening CT conducted three weeks earlier (Figure 1). On the mediastinal window setting, a 1.6 cm well-demarcated, minimally enhancing nodule was seen in the LUL intersegmental area, indicative of an enlarged lymph node (LN). Given the lesion’s subpleural location, its persistence, and the patient’s history of bladder cancer, we considered a malignant lesion in the differential diagnosis and proceeded with further evaluation.

Tumor marker evaluation revealed carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cytokeratin 19 fragment antigen 21-1 (CYFRA 21-1) levels within normal limits. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) displayed hypermetabolism with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 4.8 in the LUL nodule, making it challenging to differentiate between inflammatory and malignant pathology. No hypermetabolism was observed in the LUL intersegmental LN or the urinary bladder, effectively ruling out recurrence suspicions.

Given the nodule’s small size, subpleural location, and coverage by rib, we anticipated that percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy would be difficult. Instead, we performed endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) on the enlarged LUL intersegmental LN, which revealed no evidence of malignancy. Consequently, we decided on a short-term follow-up.

After approximately 1.5 months, repeat contrast-enhanced chest CT showed slight enlargement of the LUL nodule (1.5 cm) with new cavitary changes and mild eccentric wall thickening (Figure 2). Additionally, the mediastinal setting revealed new para-aortic LN enlargement with suspected central necrosis, while the enlarged LUL intersegmental LN showed no significant change. Given the high likelihood of malignancy, we proceeded with video-assisted surgical biopsy on the LUL cavitary nodule and LN.

Surgery was performed two weeks after the last CT scan. Intraoperatively, the cavitary nodule appeared firm and ring-like, adhering to the pleura, with LN enlargement also observed. Both the cavitary nodule and LN demonstrated malignancy on frozen section analysis, prompting a left upper lobectomy and ipsilateral hilar and mediastinal LN dissection.

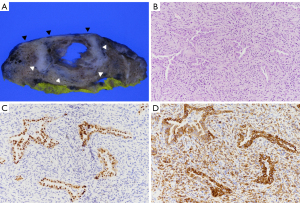

Final pathology revealed 85% spindle cell and 15% adenocarcinoma components, confirming pleomorphic carcinoma (Figure 3). Visceral pleural invasion was identified, and the lobectomy site resection margin was clear. While mediastinal LN metastasis was present, no additional LN metastases were detected (pT2aN2). Immunohistochemistry showed thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) positivity in the adenocarcinoma component, with pancytokeratin expression in both components. A high expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) was noted, with no evidence of Kirsten rat sarcoma virus (KRAS), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation, or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement.

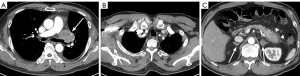

The patient was diagnosed with stage IIIA disease. Given the poor prognosis associated with pleomorphic carcinoma and mediastinal LN metastasis, we planned additional concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT). However, he developed right shoulder pain, and a contrast-enhanced chest CT on postoperative day 30 showed a large recurrent tumor along the lobectomy stump, new metastatic LNs in the mediastinum, and intramuscular metastases in the right subscapularis muscle, left chest wall, and neck, as well as metastases in the adrenal glands and pancreatic tail (Figure 4). A newly developed left cheek skin nodule was confirmed as metastatic via punch biopsy. The patient is currently undergoing CCRT.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Publication of this article and accompanying images was waived from patient consent according to the Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital institutional review board.

Discussion

Pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung is classified as a sarcomatoid carcinoma by the World Health Organization (WHO) and is a poorly differentiated NSCLC subtype with both epithelial and sarcomatoid features (1,8). Histologically, it consists of at least 10% spindle or giant cells, along with components of mixed adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or large cell carcinoma (2). It predominantly affects older male smokers, has an incidence of 0.1–0.4%, and manifests with nonspecific symptoms that range from asymptomatic to cough, sputum, hemoptysis, chest pain, and weight loss (1).

Radiologically, pleomorphic carcinoma often appears as a large peripheral mass (6,7). Masses larger than 5 cm usually show central low attenuation due to hemorrhage or necrosis, correlated with a poor prognosis. Central necrosis may also cause cavitary changes, and pleural invasion is commonly seen.

Due to the tumor’s mixture of cancer types, a definitive diagnosis can be challenging with small biopsy and cytology specimens, often necessitating resection specimens for accuracy (8). This histologic complexity might lead to an underestimation of the incidence of pleomorphic carcinoma. In several cases, the percutaneous biopsy was initially interpreted as a malignant epithelial tumor, and a definitive diagnosis of pleomorphic carcinoma was made only upon surgical resection. Generally, pleomorphic carcinoma is known to be composed of intermingled sarcomatoid and NSCLC components. Thus, its diagnosis is usually straightforward. However, if the biopsy specimen is too small or if there is a prominent desmoplastic reaction as seen in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, spindle cells may be observed reactively within the desmoplastic stroma, potentially leading to an underestimation of pleomorphic carcinoma. The tumor’s diverse histologic characteristics are also evident in immunohistochemistry, which reveals both epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. Carcinoma components typically exhibit positivity for cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen, while mesenchymal differentiation is indicated by vimentin staining (9). Given these diagnostic challenges, immunostaining with cytokeratin, especially pancytokeratin, which robustly stains both tumor components, should be performed to minimize the risk of underestimating pleomorphic carcinoma when aggressive features are present.

Our case initially presented as a small peripheral lung nodule. Although the overall size did not increase dramatically, it exhibited cavitary changes within a short period. Radiologic-pathologic correlation revealed that approximately half of the solid tumor underwent cavitary transformation and a substantial amount of the spindle cell carcinoma component around the cavity that displayed high-grade pleomorphism and marked nuclear atypia. These findings suggested that early tumor necrosis was induced even while the lesion was small, leading to early cavitary change. This was further supported by high proliferative indices, including a Ki-67 index of 35% and a high mitotic count. Moreover, as seen in our case where the sarcomatoid (spindle cell) component constituted 85% of the tumor, a predominance of sarcomatoid features was associated with a poor prognosis (10). A careful retrospective review of the imaging of our case revealed that this peripheral small lung nodule demonstrated subtle signs of pleural tagging such as subpleural linear opacities and retraction not usually observed in infection or inflammation. This suggests that when pleural tagging is present, a more proactive diagnostic plan should be considered. Moreover, when additional findings such as LN enlargement, as observed in our patient, are present, an earlier diagnosis might be possible.

Clinically, pleomorphic carcinoma shows more aggressive behavior than other NSCLCs, characterized by rapid growth and high metastatic potential. This aggressiveness results in a poorer response to treatment and a prognosis that is less favorable than other NSCLCs. Median survival ranges from 8–19 months, and cases often reveal distant metastasis shortly after surgical resection, affecting the bones, brain, adrenal glands, esophagus, kidneys, small intestine, and colon (1,10,11). Due to its propensity for early metastasis and a high recurrence rate, aggressive treatment is usually required. Whenever possible, complete resection is pursued, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy as necessary. However, responses to cytotoxic agents and radiation therapy have generally been poor (12).

Recently, cases have demonstrated responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), offering hope for better therapeutic outcomes (13). PD-L1 expression is commonly observed in pleomorphic carcinoma, and studies have shown that patients with PD-L1 expression may experience prolonged survival following ICI therapy, indicating that PD-L1 might be a favorable biomarker for ICI efficacy. Nonetheless, even in PD-L1-positive cases, some patients fail to respond to ICIs, indicating that additional complex factors may affect treatment responses.

Radiomics analyses have been conducted to identify prognostic factors in pleomorphic carcinoma. In one study, prognostic models for pleomorphic carcinoma patients were analyzed using both semantic and radiomics features (14). Semantic analysis revealed that peripherally located tumors with cavitary changes and high SUVmax on PET-CT were associated with a poorer prognosis. Conversely, patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy post-surgery demonstrated improved survival rates. From a radiomics perspective, higher CT first-order energy values were correlated with a poorer prognosis. However, risk estimation based solely on a single feature is limited. Combining semantic and radiomics characteristics resulted in the highest predictive accuracy, particularly in cases with high SUVmax and high CT first-order energy values. Although CT radiomics was not performed in our case, the SUVmax on PET-CT was 4.8, which is not exceedingly high.

A study examined tumor spread through air spaces (STAS) in patients with pleomorphic carcinoma (15). Approximately 40% of patients who underwent surgery for pleomorphic carcinoma had tumor STAS identified. These patients exhibited significantly lower overall and recurrence-free survival rates compared to those in the tumor STAS-negative group, indicating that tumor STAS may be a valuable prognostic indicator post-surgery. However, in our case, tumor involvement was limited to a localized area in the lung, and tumor STAS was negative.

To our knowledge, there have been no previous case reports of pleomorphic carcinoma that began as a small peripheral nodule, exhibited early cavitary changes and LN metastasis, and rapidly progressed to systemic dissemination after surgery. Even small pulmonary nodules that display subtle radiologic findings such as pleural tagging and/or LN enlargement require a more rigorous and proactive diagnostic evaluation. Furthermore, considering the absence of several poor prognostic factors identified in previous studies, this case suggests that additional factors may influence prognosis, warranting further research.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-2024-2475/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Publication of this article and accompanying images was waived from patient consent according to the Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital institutional review board.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chang YL, Lee YC, Shih JY, Wu CT. Pulmonary pleomorphic (spindle) cell carcinoma: peculiar clinicopathologic manifestations different from ordinary non-small cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer 2001;34:91-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki T, Ishii G, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Mizuno T, Yokose T, Suzuki K, Ochiai A. Pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung: clinicopathologic characteristics of 70 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1727-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuki T, Sakuma T, Ohbayashi C, Yoshimura M, Tsubota N, Okita Y, Okada M. Pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung: a surgical outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:399-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen F, Sonobe M, Sato T, Sakai H, Huang CL, Bando T, Date H. Clinicopathological characteristics of surgically resected pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:1037-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ito K, Oizumi S, Fukumoto S, Harada M, Ishida T, Fujita Y, Harada T, Kojima T, Yokouchi H, Nishimura MHokkaido Lung Cancer Clinical Study Group. Clinical characteristics of pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer 2010;68:204-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim TH, Kim SJ, Ryu YH, Lee HJ, Goo JM, Im JG, Kim HJ, Lee DY, Cho SH, Choe KO. Pleomorphic carcinoma of lung: comparison of CT features and pathologic findings. Radiology 2004;232:554-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim TS, Han J, Lee KS, Jeong YJ, Kwak SH, Byun HS, Chung MJ, Kim H, Kwon OJ. CT findings of surgically resected pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung in 30 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;185:120-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicholson AG, Tsao MS, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, Brambilla E, Cooper WA, Dacic S, Jain D, Kerr KM, Lantuejoul S, Noguchi M, Papotti M, Rekhtman N, Scagliotti G, van Schil P, Sholl L, Yatabe Y, Yoshida A, Travis WD. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:362-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhao L, Jing H, Sang S, Du J. Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7465. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossi G, Cavazza A, Sturm N, Migaldi M, Facciolongo N, Longo L, Maiorana A, Brambilla E. Pulmonary carcinomas with pleomorphic, sarcomatoid, or sarcomatous elements: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 75 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:311-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fishback NF, Travis WD, Moran CA, Guinee DG Jr, McCarthy WF, Koss MN. Pleomorphic (spindle/giant cell) carcinoma of the lung. A clinicopathologic correlation of 78 cases. Cancer 1994;73:2936-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bae HM, Min HS, Lee SH, Kim DW, Chung DH, Lee JS, Kim YW, Heo DS. Palliative chemotherapy for pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma. Lung Cancer 2007;58:112-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayashi K, Tokui K, Inomata M, Azechi K, Mizushima I, Takata N, Taka C, Okazawa S, Kambara K, Imanishi S, Miwa T, Hayashi R, Matsui S, Nomura S, Tobe K. Case Series of Pleomorphic Carcinoma of the Lung Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. In Vivo 2021;35:1687-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim C, Cho HH, Choi JY, Franks TJ, Han J, Choi Y, Lee SH, Park H, Lee KS. Pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung: Prognostic models of semantic, radiomics and combined features from CT and PET/CT in 85 patients. Eur J Radiol Open 2021;8:100351. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama S, Murakami T, Tao H, Onoda H, Hara A, Miyazaki R, Furukawa M, Hayashi M, Inokawa H, Okabe K, Akagi Y. Tumor Spread Through Air Spaces Identifies a Distinct Subgroup With Poor Prognosis in Surgically Resected Lung Pleomorphic Carcinoma. Chest 2018;154:838-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]