Multidisciplinary treatment of internal iliac pseudoaneurysm-sigmoid fistula: a case description

Introduction

Iliac artery-enteric fistula represents a rare form of aortoenteric fistula (AEF). AEF can be categorized into primary and secondary types. Primary AEF is particularly uncommon and more severe, with an incidence ranging from 0.04% to 0.07% (1). The most frequent site for AEF development is duodenum, followed by the jejunum, ileum, colon, and stomach. Primary AEF is predominantly associated with pseudoaneurysms, primarily stemming from atherosclerosis, with a few cases attributed to tumors, diverticulosis, sepsis, syphilis, tuberculosis, and radiation therapy (2). Conversely, secondary AEF typically arises from aortic reconstruction or graft infection, with an incidence of 1% in aortic reconstruction patients. In contrast, iliac artery-intestinal fistulas are most primary, with secondary occurrences being less common (3-5). This paper reports a case of left internal iliac artery pseudoaneurysm-intestinal fistula with massive hemorrhage admitted to the General Hospital of Western Theater Command from November, 2019. Following prompt treatment, the patient underwent a 5-year follow-up, revealing a favorable prognosis.

Case presentation

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

A 65-year-old male presented with persistent hematochezia lasting over four months, which acutely worsened prior to admission. The patient reported episodes of bloody stool, with an estimated volume of 800 mL per episode and a cumulative blood loss exceeding 2,000 mL over the preceding three days. He denied associated symptoms such as chills, fever, or abdominal pain.

Past medical history

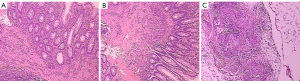

Two months ago, a colonoscopy identified a rectal mass characterized by chronic active inflammation with erosive ulceration. Subsequent laparotomy confirmed abdominal tuberculosis, revealing miliary nodules and positive acid-fast staining (Figure 1). The patient is currently receiving anti-tuberculosis therapy.

Physical examination

The patient had a body temperature of 36.5 ℃, heart rate of 70 bpm, respiratory rate of 20/min, blood pressure 120/74 mmHg, and blood oxygen saturation at 98%. No abnormal cardiopulmonary findings. Abdominal exam showed flat abdomen, soft wall, mild tenderness below xiphoid process, and no palpable mass.

Admission laboratory findings and imaging results

On the first day of admission, laboratory tests revealed brown loose stools with positive occult blood, accompanied by mild anemia [red blood cell (RBC) 2.39×1012/L, hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL, hematocrit 28.4%] and normal coagulation parameters. By the fourth day, chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated scattered pulmonary nodules (largest 0.7 cm in the left lung), opacities, enlarged lymph nodes, and left pleural thickening with minimal effusion. Abdominal CT findings included intestinal wall thickening, enhancement of the descending and sigmoid colon, small pelvic effusion, and focal dilation of the left internal iliac artery (Figure 2). These findings collectively suggest gastrointestinal bleeding with possible inflammatory or infectious involvement, warranting further investigation.

Treatment procedure

On the fifth day of admission, the patient experienced a sudden episode of hematochezia amounting to an estimated 1,000 mL, leading to hemorrhagic shock and a decline in blood pressure to 50/30 mmHg. Immediate interventions comprised the intravenous administration of 500 mL of hydroxyethyl starch and 3 mg of somatostatin. and an urgent request for cross-matching and the transfusion of 3 units of leukocyte-depleted red blood cells.

Following discussions among the Radiology, Gastrointestinal Surgery, and Infectious Disease multidisciplinary teams (MDT). Firstly, the patient’s life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding and severe abdominal tuberculosis with extensive adhesions posed significant challenges for any repeat surgical exploration. Additionally, surgical hemostasis might delay critical care and raise risk peritoneal infection disseminating to diffuse peritonitis. The last but the most important point is that the radiologist reviewed images again, indicating a high suspicion internal iliac pseudoaneurysm-sigmoid fistula formation. Thus, an emergency interventional treatment was recommended as the initial approach.

Interventional angiography and treatment

The angiography revealed a tumor-like dilation at the proximal portion of the left internal iliac artery with contrast agent spillover. Subsequent embolization with 7 pushable embolization coils effectively controlled the contrast agent leakage (Figure 3). The equipment utilized comprised an Angiographic Catheter, 5F, from Terumo (model RF*dg35008M, Japan), 5 Nester® Embolization Coils (MWCE-35-14-10-NESTER), 1 MReye® Embolization Coil (IMWCE-35-5-8) and 1 MReye® Embolization Coil (IMWCE-35-5-10) from Cook Incorporated (USA). The patient experienced hemorrhagic shock during the procedure but responded well to symptomatic and supportive care, including rehydration, and blood transfusion. The patient’s blood pressure improved to 106/70 mmHg, the red blood cell count was 2.32×1012/L, and the hemoglobin concentration was 6.4 g/dL after interventional treatment 12 hours.

Follow-up

During the 5-year post-discharge follow-up, the patients achieved good results after systemic anti-tuberculosis treatment. no hematochezia was recorded.

Discussion

The patient in this case did not present with noticeable bleeding points during the initial colonoscopy, nor were a pseudoaneurysm and related lesions discovered during exploratory laparotomy. Based on biopsy results, the diagnosis was undiagnosed of the potential abdominal (peritoneal and intestinal) tuberculosis. Systemic anti-tuberculosis therapy was administered, but the patient’s lower gastrointestinal bleeding symptoms were not adequately addressed. Upon transfer to our hospital, comprehensive thoracoabdominal CT with contrast enhancement highlighted a pseudoaneurysm dilation of the left internal iliac artery during the arterial phase scan. However, the anatomical relationship between the arterial wall and intestine was unclear, with adhesions. Initial radiological imaging report did not reveal the presence of a small fistula. Due to the rare nature of this case, the radiologist failed to integrate the clinical history with the imaging findings, resulting in an unnoticed potential association between the pseudoaneurysm and lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Following emergency interventional therapy, we conducted multiplanar reconstruction of the original CT image in this case, revealing a small fistula about 2 mm between the pseudoaneurysm and sigmoid colon. Timely identification of the pseudoaneurysm on CT imaging and provision of a detailed report could have prevented the severe hemorrhage on the fifth day of admission, thereby significantly reducing patient risk. This case suggests that radiologists should not overlook abnormal findings and details when interpreting image, emphasizing the crucial need to integrate imaging findings with the patient’s medical history, for a comprehensive analysis and correlation to make informed judgments. Furthermore, this case underscores the pivotal role of CT examinations and multiplanar reconstructions in diagnosing challenging conditions.

Internal iliac artery pseudoaneurysm with sigmoid colon fistula presents as a severe gastrointestinal bleeding condition caused by an abnormal connection between the internal iliac artery and sigmoid colon (3). In this case, the patient was diagnosed with tuberculosis, chest CT revealing imaging findings consistent with pulmonary tuberculosis, including numerous miliary nodules in the abdominal cavity, and positive acid-fast staining on biopsy, thus confirming the diagnosis abdominal tuberculosis. Tuberculous AEF carries a significantly high mortality rate, with a rate as high as 50% within 30 days after surgical repair (6).

The CT image in this case depicted thickening of the pseudoaneurysm wall with an indistinct boundary with the intestine, raising the suspicion for intestinal or adjacent the pseudoaneurysm walls tuberculosis. The pressure exerted by the pseudoaneurysm on the lateral wall can result in necrosis and inflammatory adhesion of intestinal tissues, culminating in the development of an arterial-intestinal fistula, specifically a primary iliac artery-intestinal fistula. The process is characterized by lower gastrointestinal bleeding, initially manifesting as a small amount of blood in the stool, potentially progressing to life-threatening massive bleeding. This hypothesis may be the mechanism underlying lower gastrointestinal bleeding in our reported case.

Patients with internal iliac pseudoaneurysm-sigmoid fistula typically present with abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, and pulsatile abdominal masses, with 94% experiencing gastrointestinal bleeding and approximately 11% exhibiting all three symptoms concurrently (7). In this case, the patient primarily exhibited lower gastrointestinal bleeding, accompanied by classical herald bleeding, which can progress to fatal hemorrhage within days if not promptly diagnosed and treated, posing a significant threat to the patient’s life.

The preoperative diagnosis of internal iliac pseudoaneurysm-sigmoid fistula poses significant challenges, with only 33% to 50% of patients receiving a clear diagnosis preoperatively (8). Endoscopy, CT, angiography, and radionuclide scanning contribute to the diagnostic process but lack specificity (9), with enhanced CT yielding superior diagnostic outcomes (10). If initial investigations remain inconclusive, surgical exploration is warranted for confirmation. A heightened suspicion of AEF is essential for patients with a history of abdominal aortic pseudoaneurysm and unexplained gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Surgery is vital in saving AEF patients’ lives, including open surgery and endovascular exclusion. Open surgery poses high risks, more challenges, and notable mortality and disability rates, with a postoperative mortality ranging from 36% to 77% (1,11,12). Endovascular exclusion can swiftly control bleeding, minimize surgical trauma, and is suitable for patients with compromised overall health or serious comorbidities (13). Compared to traditional open surgeries, endovascular reconstruction appears to decrease morbidity and mortality rates (14). Nevertheless, complications such as rebleeding and sepsis may impact long-term outcomes (15). Internal iliac arterio-enteric fistula and aorto-enteric fistula significantly differ in treatment and mortality. In the case of aorto-enteric fistula, treatment is only possible with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or surgery, and the mortality rate is high because it invades the great artery. In contrast, in the case of iliac arterio-fistula, not only covered stenting but also embolization can be an option, and the mortality rate may be relatively low because it is smaller than the aorta (16).

Patients with fistulae are at risk of retrograde infection and graft infection, hence requiring active anti-infective treatment postoperatively. If blood cultures show positive results, antibiotics should be administered for a minimum of 4 to 6 weeks to effectively reduce infection-related complications (3,17). Proactive anti-infective management can effectively alleviate the patient’s condition.

When using coil embolization to treat an arterial pseudoaneurysm, it is crucial to ensure that the coil remains inside the pseudoaneurysm to form a thrombus for hemostasis and to prevent migration into a fistula tract. This helps prevent inflammatory spread along the coil into the pseudoaneurysm during poorly controlled intra-abdominal inflammation, leading to tissue breakdown, abscess formation, and potential coil detachment, resulting in severe or even fatal gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

The elderly patient in this case had multiple organ pathologies, leading to a complex clinical condition with high treatment difficulty and risks. In managing this uncommon case, the MDT model plays a pivotal role in achieving a clear diagnosis, devising optimal treatment strategies, and ensuring successful outcomes. The MDT involves collaborative discussions among multiple clinical experts to analyze a clinical condition and recommend the most effective treatment approach. This collaborative framework facilitates the tailored and precise development of diagnosis and treatment plans for individual patients, enhancing survival rates and overall satisfaction (18). After assessing the CT findings and reviewing the previous pathological biopsy results, the gastrointestinal surgery team concluded that the severity of abdominal inflammation, extensive adhesions, and the patient’s unstable hemodynamics precluded the consideration of a repeat laparotomy for hemostasis. Eventually, an interventional treatment plan was established, streamlining the process and averting unnecessary examinations and surgical interventions. This plan included preoperative medical management, interventional procedures, and postoperative infection control measures, effectively preventing the need for secondary surgery due to misdiagnosis. The favorable outcome in the later stages was primarily attributed to the individualized treatment plan formulated under the MDT. The management of this case exemplifies the advantages of the MDT approach.

Conclusions

For arterial pseudoaneurysms detected on CT, comprehensive observation and integrated clinical correlation are crucial to avoid misdiagnosis. Patients with suspected iliac artery-enteric fistulas should undergo early contrast-enhanced CT and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) examinations to confirm the diagnosis. In cases of hemodynamically unstable patients, initial intervention with coil embolization for pseudoaneurysm hemostasis can save lives and lead to improved prognosis.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Funding: This study was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1701/coif). F.D. reports that this study was supported by the Foundation of General Hospital of Western Command (Grant Nos. 2024-YGJS-A05 and 2024-YGJS-B01). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Georgeades C, Zarb R, Lake Z, et al. Primary Aortoduodenal Fistula: A Case Report and Current Literature Review. Ann Vasc Surg 2021;74:518.e13-518.e23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lukens ML, Cardella JF, Fox PS. Progressive arteriocolonic fistulization following pelvic irradiation. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1995;6:615-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Policha A, Baldwin M, Mussa F, Rockman C. Iliac Artery-Uretero-Colonic Fistula Presenting as Severe Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage and Hematuria: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Ann Vasc Surg 2015;29:1656.e1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu X, Yan L. A secondary abdominal aorta-duodenal fistula accompanied with acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome presented with recurrent sepsis: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2024;24:669. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kahlberg A, Rinaldi E, Piffaretti G, Speziale F, Trimarchi S, Bonardelli S, Melissano G, Chiesa R. MAEFISTO collaborators. Results from the Multicenter Study on Aortoenteric Fistulization After Stent Grafting of the Abdominal Aorta (MAEFISTO). J Vasc Surg 2016;64:313-320.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allins AD, Wagner WH, Cossman DV, Gold RN, Hiatt JR. Tuberculous infection of the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta: case report and literature review. Ann Vasc Surg 1999;13:439-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karthaus EG, Post IC, Akkersdijk GJ. Spontaneous aortoenteric fistula involving the sigmoid: A case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;19:97-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmad BS, Haq MU, Munir A, Abubakar Mohsin Ehsanullah SA, Ashraf P. Aortoenteric fistula - A fatal cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Can it be missed? - A case report. J Pak Med Assoc 2018;68:1535-7.

- Busuttil SJ, Goldstone J. Diagnosis and management of aortoenteric fistulas. Semin Vasc Surg 2001;14:302-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mathias J, Mathias E, Jausset F, Oliver A, Sellal C, Laurent V, Regent D. Aorto-enteric fistulas: a physiopathological approach and computed tomography diagnosis. Diagn Interv Imaging 2012;93:840-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beuran M, Negoi I, Negoi RI, Hostiuc S, Paun S. Primary Aortoduodenal Fistula: First you Should Suspect it. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2016;31:261-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nayeemuddin M, Pherwani AD, Asquith JR. Imaging and management of complications of open surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Clin Radiol 2012;67:802-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burks JA Jr, Faries PL, Gravereaux EC, Hollier LH, Marin ML. Endovascular repair of bleeding aortoenteric fistulas: a 5-year experience. J Vasc Surg 2001;34:1055-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindblad B, Holst J, Kölbel T, Ivancev KMalmö Vascular Centre Group. What to do when evidence is lacking--implications on treatment of aortic ulcers, pseudoaneurysms and aorto-enteric fistulae. Scand J Surg 2008;97:165-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung J. Management of Aortoenteric Fistula. Adv Surg 2018;52:155-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dimech AP, Sammut M, Cortis K, Petrovic N. Unusual site for primary arterio-enteric fistula resulting in massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding - A case report on presentation and management. Int J Surg Case Rep 2018;49:8-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh K, Guerges M, Rost A, Russo N, Aparajita R, Schor J, Deitch J. Endovascular Management of Bleeding Aortoenteric Fistula May be Feasible as a Definitive Repair. Ann Vasc Surg 2022;83:378.e1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bilfinger TV, Albano D, Perwaiz M, Keresztes R, Nemesure B. Survival Outcomes Among Lung Cancer Patients Treated Using a Multidisciplinary Team Approach. Clin Lung Cancer 2018;19:346-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]