The diagnostic value of ultra-microangiography for biliary atresia

Introduction

Biliary atresia (BA) is a serious biliary disease in newborns and infants that leads to progressive liver fibrosis (1). If left untreated, most patients die before the age of 2 years (2). Thus, the early and accurate diagnosis of BA is crucial. Ultrasound (US) is the preferred imaging examination method for diagnosing BA, and plays an important role in the clinical diagnosis of and treatment plans for BA. BA has some specific US features, including a small gallbladder volume, a rigid gallbladder morphology, a triangular cord (TC) sign in front of the portal vein, an inability to display of the common bile duct, and an enlarged hepatic artery (HA) diameter (3).

There are a number of reasons for changes in the hepatic arterial system of BA patients. First, due to liver tissue fibrosis and active inflammatory activity, many inflammatory substances have vascular activity, causing vasodilation, increased blood flow velocity, and increased blood flow. Second, the HA is the only blood supply vessel to the biliary system. Patients with BA have severe inflammation and fibrosis of the bile duct, and the normal structure of the bile duct wall is damaged. The peripheral blood supply arteries are also damaged to varying degrees, resulting in increased circulation resistance, vasodilation, and increased blood flow velocity (4,5). Research (6,7) has shown that using color Doppler flow imaging (CDFI) to detect positive signs of blood flow under the liver capsule has certain diagnostic value for BA. However, the intensity of blood flow signals in microvessels is weak, and their flow velocity is very slow. Traditional CDFI technology is limited by its real-time imaging requirements and US system data processing capabilities, and its blood flow detection sensitivity cannot meet the imaging requirements of human microvascular structures.

Ultra-microangiography (UMA) is a new real-time US microvascular imaging technology, which has two core technologies: high frame rate plane wave imaging technology, and an adaptive spatiotemporal wall-filtering algorithm. It can obtain high-quality raw data with high sampling efficiency and preserve slow blood flow signals to a great extent. These two core technologies have enabled it surpassing traditional CDFI imaging, greatly improving the sensitivity and spatial resolution of blood flow detection, and enabling it to display microvascular structures that CDFI cannot display. Xu et al. (8) confirmed that US elastography combined with UMA has high diagnostic value for primary Sjogren’s syndrome, but there are currently no reports on UMA in children with BA at home and abroad. Therefore, this study aimed to detect and quantify the subcapsular microvessels in the livers of pediatric patients by fixing the imaging parameters of CDFI and UMA, and to analyze and compare the results, thereby exploring the diagnostic value of UMA in BA. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1586/rc).

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (No. SWYX2024-338), and the requirement of individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

The data of 52 patients diagnosed with BA via intraoperative cholangiography or surgical exploration at Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University from January 2022 to February 2024 were retrospectively collected. Among the 52 patients, 5 were excluded due to incomplete US examination data, 2 due to unclear US images, and 3 due to incomplete clinical data. Thus, ultimately, 42 patients were included in the study as the BA group. These patients had an average age of 67.3±51.5 days (range, 6–160 days), and 22 were male and 20 were female. An additional 105 newborns and infants admitted to the Pediatric Surgery and Neonatology Department of the Hospital for jaundice with similar gender ratios and ages were enrolled in the study as control subjects. However, 12 of these subjects were excluded due to non-conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, which is related to breastfeeding or premature birth, 3 due to histologically confirmed Alagille syndrome, 7 due to incomplete US examination data, 3 due to unclear US images, and 4 due to incomplete clinical data. Thus, ultimately, 76 infants were included as the control group (Figure 1). These patients had an average age of 25.4±33.8 days (range, 1–124 days), and 40 were male and 36 were female. Due to the retrospective observational nature of this study, which only collected existing medical records for analysis and did not intervene in the treatment processes and plans of patients, and as all the data analyzed were anonymous, written informed consent was not required.

This study used the Mindray Resona R9Q ultrasound scanner (Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) with the L15-3WU probe. The probe is equipped with a two-dimensional (2D) imaging mode for the pediatric abdomen, and also has UMA and CDFI detection functions. The 2D US imaging mode has a frequency of 3.8–9 MHz and a gain of 50–65 dB. Both the UMA and CDFI were equipped with a color pixel percentage (CPP) measurement kit. The CPP measurement frame had a fixed size (i.e., width of 2 cm, a height of 0.5 cm), and the parameters were set to a frequency of 7.2 MHz, a gain of 40 dB, and a pulse repetition frequency of 0.5 kHz.

All the subjects were fasted for 4 hours, and placed in a supine position in a quiet state to undergo the 2D US, CDFI, and UMA examinations. 2D US was used to measure the maximum length (L) and width (W) of the gallbladder. The inner diameter of the right HA was measured in front of the right portal vein, and the thickest part of the TC was measured in front of the transverse part of the left portal vein. To avoid the influence of liver edge curvature and respiratory motion on measurement data, we tried to employ CDFI and UMA detection at the end of exhalation in the flatter edge of the right lobe of the liver. CDFI and UMA quantitative tests were performed on the region of interest (ROI), with 10 sets of data measured for each subject using both tests, and the average taken. All procedures were independently performed by two physicians with experience in pediatric abdominal US examination (S.L. had 18 years of experience, and L.D. had 8 years of experience). Simultaneously, the clinical information (age and weight) and laboratory indicators, such as gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), total bilirubin (TB), and direct bilirubin (DB), of the subjects were collected.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normally distributed measurement data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and were compared using the t test. The non-normally distributed continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and the categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the CPPUMA in the diagnosis of BA, and to calculate the optimal critical value of the CPPUMA for the diagnosis of BA. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The intragroup correlation coefficient was used to determine the consistency of the evaluations between the observers.

Results

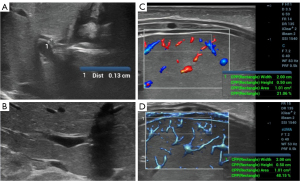

Within the same ROI, UMA displayed more microvessels than CDFI. Both the BA and control groups had higher CPPs measured by UMA (CPPUMA) than CPPs measured by CDFI (CPPCDFI). The comparison of the CPPUMA values between the BA and control groups, the comparison of the CPPUMA and CPPCDFI values within the BA group, and the comparison of the CPPUMA and CPPCDFI values within the control group all showed statistically significant differences (P=0.001), but no statistically significant difference was observed in the CPPCDFI values between the BA and control groups (P=0.055) (Table 1, Figures 2-4).

Table 1

| Ultrasound parameter | Control (n=76) | Biliary atresia (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPPUMA (%) | 60.7±5.7 (47.6–66.8) | 72.2±5.6 (64.6–88.6) | 0.001* |

| CPPCDFI (%) | 22.1±4.1 (15.4–28.7) | 24.9±4.4 (18.7–39.9) | 0.055 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Unless otherwise noted, the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, with the range in parentheses. *, an unpaired t-test was used for the statistical comparison; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for the statistical comparison. UMA, ultra-microangiography; CDFI, color Doppler flow imaging; CPPUMA, color pixel percentage measured by ultra-microangiography; CPPCDFI, color pixel percentage measured by color Doppler flow imaging.

There was no significant difference between the BA and control groups in terms of age and weight (P>0.05). However, there were statistically significant differences between the BA and control groups in terms of the HA diameter, GGT, TB, DB, L, and W (P<0.05) (Tables 2,3).

Table 2

| Variable | Control (n=76) | Biliary atresia (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male:female (n) | 40:36 | 22:20 | 0.492* |

| Age (days) | 25.4±33.8 (1–124) | 67.3±51.5 (6–160) | 0.057 |

| TB (mg/dL) | 93.2±69.2 (8.2–270.9) | 220.0±115.1 (72.8–425.3) | 0.003 |

| DB (mg/dL) | 10.5±12.8 (0.8–89.1) | 108.6±58.7 (36.4–230.2) | 0.001 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 193.0±209.5 (38–1,374) | 526.9±329.5 (65–1,139) | 0.005 |

| Weight (g) | 3,249.5±786.6 (1,870–5,160) | 4,323.3±902.6 (3,150–6,250) | 0.613 |

Unless otherwise noted, the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, with the range in parentheses. *, Fisher’s exact test was used for the statistical comparison; otherwise, an unpaired t-test was used for the statistical comparison. TB, total bilirubin; DB, direct bilirubin; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase.

Table 3

| Ultrasound parameter | Control (n=76) | Biliary atresia (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPPUMA (%) | 60.7±5.7 (47.6–66.8) | 72.2±5.6 (64.6–88.6) | 0.001 |

| CPPCDFI (%) | 22.1±4.1 (15.4–28.7) | 24.9±4.4 (18.7–39.9) | 0.055 |

| HA (mm) | 1.16±0.29 (0.7–1.6) | 2.59±0.25 (2.1–3) | 0.007 |

| TC (mm) | 0 | 3.5±1.4 (2.4–7.8) | 0.001 |

| L (mm) | 27.8±3.5 (19–37) | 15.2±6.7 (0–28) | 0.005 |

| W (mm) | 8.1±1.7 (5–12) | 3.5±1.3 (0–6) | 0.001 |

Unless otherwise noted, the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, with the range in parentheses. An unpaired t-test was used for the statistical comparison. CPPUMA, color pixel percentage measured by ultra-microangiography; CPPCDFI, color pixel percentage measured by color Doppler flow imaging; HA, hepatic artery; TC, triangular cord; L, maximum length of gallbladder; W, maximum width of gallbladder.

The CPPUMA values in the BA group were significantly correlated with HA, TC, L, and DB, but were not significantly correlated with age, weight, GGT, TB, and W (Table 4).

Table 4

| Ultrasound parameter | Analysis | GGT | TB | DB | Weight | Age | HA | TC | L | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPPUMA | Pearson correlation | 0.178 | 0.216 | 0.375** | 0.247 | 0.247 | 0.760** | 0.736** | −0.654* | −0.381 |

| Sig (bilateral) | 0.189 | 0.110 | 0.004 | 0.066 | 0.066 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.021 | 0.222 |

*, a significant correlation at the 0.05 level (bilateral); **, a significant correlation at the 0. 01 level (bilateral). CPP, color pixel percentage; UMA, ultra-microangiography; CPPUMA, color pixel percentage measured by ultra-microangiography; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; TB, total bilirubin; DB, direct bilirubin; HA, hepatic artery; TC, triangular cord; L, maximum length of gallbladder; W, maximum width of gallbladder.

We also analyzed the effect of gender on blood flow in patients with BA and found no statistically significant difference in blood flow based on gender (P>0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5

| Variable | Male | Female | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 22 | 20 | |

| CPPUMA (%) | 70.1±7.7 (57.1–82.5) | 72.8±5.8 (64.2–88.6) | 0.419 |

| CPPCDFI (%) | 24.3±3.8 (20.7–39.9) | 23.9±3.7 (18.7–29.7) | 0.849 |

Unless otherwise noted, the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, with the range in parentheses. An unpaired t-test was used for the statistical comparison. CPPUMA, color pixel percentage measured by ultra-microangiography; CPPCDFI, color pixel percentage measured by color Doppler flow imaging.

The areas under the ROC curves of the CPPUMA and CPPCDFI for BA diagnosis were 0.854 and 0.666, respectively. The optimal critical values for the CPPUMA in BA diagnosis were 66.28%, the Se was 92%, the Sp was 71%, the PPV was 85.7%, and the NPV was 95.4% (Figure 5).

The diagnostic results of the two US doctors showed good consistency, and the P values all >0.9.

Discussion

BA is a serious liver and gallbladder disease that endangers the lives of infants and young children. US is an important diagnostic method for BA. In addition to the TC sign and abnormal changes in the gallbladder, an enlarged HA diameter and positive blood flow under the liver capsule are the main features of BA (9,10). Research (6,7) has shown that using CDFI to detect positive signs of blood flow under the liver capsule has auxiliary diagnostic value for BA. However, the sensitivity of traditional CDFI blood flow detection cannot meet the imaging requirements of human microvascular architecture and the microcirculation vascular bed. UMA, a microvascular imaging technique that focuses on low-speed blood flow, can display microvascular structures that traditional color Doppler blood flow cannot display. This study used UMA and CDFI to detect and quantify the microvessels under the liver capsule of the subjects. The results showed that within the same ROI, UMA displayed more microvessels than CDFI. In the BA group and the control group, the CPPUMA values were higher than the CPPCDFI values.

According to domestic and foreign studies (11,12), the critical value of the HA diameter in infants for diagnosing BA is ≥1.5 mm. In our study, the HA diameter in all the patients in the BA group was increased. Specifically, the BA group had an average HA diameter of 2.59 (range, 2.1–3.0) mm, while the control group had an average HA diameter of 1.16 (range, 0.7–1.4) mm. Research (13,14) has shown that a TC thickness in front of the right portal vein branch ≥4 mm has certain auxiliary diagnostic value for BA as a standard. However, in this study, 14 patients with positive TC signs were assessed based on this standard, and the sensitivity was only 33.3%. This study found that all patients had clearly visible hyperechoic fibrous structures in front of the transverse part of the left portal vein, but some contained uniform echoes, while others contained scattered or bead-shape echoes. Therefore, this study used the disappearance of the parallel pipeline structure in front of the transverse part of the left portal vein as the standard, and 40 patients showed positive TC signs with an average TC thickness of 3.5 (range, 2.4–7.8) mm. Two patients presented with a parallel pipeline structure in front of the transverse part of the left portal vein, but with thickened walls and enhanced echogenicity, and fine punctate echogenicity filling inside the lumen, which was later confirmed to be BA. It may be that the patients had relatively short courses of illness (6 and 13 days, respectively), and the inflammation and fibrosis of the bile duct were mild, and had not yet caused structural damage to the bile duct wall.

In this study, the gallbladder display rate was 100% in the control group and 92.86% (39/42) in the BA group, and 3 patients had no gallbladder. In the BA group, 39 patients showed irregular and rigid gallbladder morphology, with an uneven thickening of the gallbladder wall, 37 had a gallbladder L <19 mm, and 2 had a normal gallbladder size. Among them, 1 patient showed uneven thickening and stiffness of the gallbladder wall, accompanied by an inability to display the common bile duct, and the other patient presented with a cystic mass in the porta hepatis area, and both patients were diagnosed with BA. Scholars (15) have reported that the absence of the common bile duct during US examination can be considered a positive criterion for BA. Nevertheless, evaluation based on the common bile duct alone has limitations. According to a previous study (16) of patients aged 3 months or less, the average diameter of the common bile duct is 0.69±0.48 mm, and it can contract or expand with fluctuations in bile flow. In our study, the common bile duct was detected in 4 patients in the BA group (9% false-negative results), but it was not detected in 17 patients in the control group (23% false-positive results), which is similar to the results reported by Kim et al. (11).

Research (17-19) reported that the older the age of BA patients, the higher the levels of GGT and TB. There were differences in the GGT and TB levels between the BA and control groups in this study; however, the Pearson correlation analyses between the CPPUMA values and GGT and TB were not significant (P>0.05). Due to the small number of cases in this study, there might be a bias in the age distribution, such that some indicators showed no significant correlation. We also analyzed the effect of gender on blood flow in patients with BA, but no statistically significant difference was found.

This study had some limitations. First, the dependence on surgery inevitably limits the reproducibility of the US findings. Second, this single-center retrospective study has potential bias in the population selection; thus, subsequent multicenter related research will be conducted. Finally, UMA has currently only been used in few cases to diagnose BA; thus, the sample size needs to be increased in further research.

Conclusions

Due to its high sensitivity and spatial resolution in detecting microvascular structures, UMA significantly improved the microvascular imaging compared to traditional CDFI. The quantification of the microvessels under the liver capsule in BA patients using UMA could help to improve the US diagnosis of BA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research group at the Department of Pediatric Surgery and the Department of Neonatology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University for their contribution.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1586/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1586/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (No. SWYX2024-338), and the requirement of individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Yang L, Du C, Chen W, Duan X, Zhou M, Wen H. Preliminary study on intelligent ultrasound diagnosis of biliary atresia based on deep learning. Chinese Journal of Ultrasound Imaging 2021;30:402-407.

- Wang R, Li Y. Research progress on diagnostic methods for biliary atresia. Chinese Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2021;42:837-46.

- Yu P, Dong N, Pan YK, Li L. Ultrasonography is useful in differentiating between cystic biliary atresia and choledochal cyst. Pediatr Surg Int 2021;37:731-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mo J, Sun Z, Hu R. The diagnostic value of high-frequency ultrasound in pediatric biliary atresia. International Medical and Health News 2019;25:102-4.

- Sun C, Wu B, Pan J, Chen L, Zhi W, Tang R, Zhao D, Guo W, Wang J, Huang S. Hepatic Subcapsular Flow as a Significant Diagnostic Marker for Biliary Atresia: A Meta-Analysis. Dis Markers 2020;2020:5262565. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu C, Zhan J. Research advances in the changes of hepatic vascular system in biliary atresia. Chinese Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2019;40:466-70.

- Lee MS, Kim MJ, Lee MJ, Yoon CS, Han SJ, Oh JT, Park YN. Biliary atresia: color doppler US findings in neonates and infants. Radiology 2009;252:282-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu Z, Li R, Xia B, Jiang M, Wu X, Zhang X, Pan J, Chen J. Combination of ultra-micro angiography and sound touch elastography for diagnosis of primary Sjögren's syndrome: a diagnostic test. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023;13:7170-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- dos Santos JL, da Silveira TR, da Silva VD, Cerski CT, Wagner MB. Medial thickening of hepatic artery branches in biliary atresia. A morphometric study. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:637-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masuya R, Muraji T, Ohtani H, Mukai M, Onishi S, Harumatsu T, Yamada K, Yamada W, Kawano T, Machigashira S, Nakame K, Kaji T, Ieiri S. Morphometric demonstration of portal vein stenosis and hepatic arterial medial hypertrophy in patients with biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 2019;35:529-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim WS, Cheon JE, Youn BJ, Yoo SY, Kim WY, Kim IO, Yeon KM, Seo JK, Park KW. Hepatic arterial diameter measured with US: adjunct for US diagnosis of biliary atresia. Radiology 2007;245:549-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou Y, Jiang M, Tang ST, Yang L, Zhang X, Yang DH, Xiong M, Li S, Cao GQ, Wang Y. Laparoscopic finding of a hepatic subcapsular spider-like telangiectasis sign in biliary atresia. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:7119-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HJ, Lee SM, Park WH, Choi SO. Objective criteria of triangular cord sign in biliary atresia on US scans. Radiology 2003;229:395-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Guindi MA, Sira MM, Sira AM, Salem TA, El-Abd OL, Konsowa HA, El-Azab DS, Allam AA. Design and validation of a diagnostic score for biliary atresia. J Hepatol 2014;61:116-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Azuma T, Nakamura T, Nakahira M, et al. Pre-operative ultrasonographic diagnosis of biliary atresia--with reference to the presence or absence of the extrahepatic bile duct. Pediatr Surg Int 2003;19:475-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chau P, Moses D, Pather N. Normal morphometry of the biliary tree in pediatric and adult populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol 2024;176:111472. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou L, Shan Q, Tian W, Wang Z, Liang J, Xie X. Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Biliary Atresia: A Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;206:W73-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoon HM, Suh CH, Kim JR, Lee JS, Jung AY, Cho YA. Diagnostic Performance of Sonographic Features in Patients With Biliary Atresia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Ultrasound Med 2017;36:2027-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weng Z, Zhou W, Wu Q, Ma H, Fang Y, Dang T, Ling W, Liu M, Zhou L. Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase Combined With Conventional Ultrasound Features in Diagnosing Biliary Atresia: A Two-Center Retrospective Analysis. J Ultrasound Med 2022;41:2805-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]