A case description of mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma, which, as an unusual neoplasm, was removed using the standard cold snare polypectomy method

Introduction

Mucosal Schwann cell hamartomas (MSCH) are rare neurogenic tumors located in the lamina propria of the gastrointestinal tract (1). They most commonly appear in the distal colon, usually presenting as small, solitary, sessile polyps measuring between 1 to 6 mm (2,3). These polyps are asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally during screening colonoscopies (2,3). MSCH have also been detected in the gastroesophageal junction, gastric antrum, and gallbladder (4-8). MSCH of the gastrointestinal tract are most frequently found in middle-aged women. Histological analysis of these polyps shows spindle-shaped cells without ganglion cells within their specific layer of the mucous membrane (1,9). Immunohistochemical testing indicates strong and widespread immunoreactivity with antibodies targeting the S100 protein (9). Given the rarity of mucosal Schwann cell hamartomas, we present one such case to contribute to the existing literature.

Case presentation

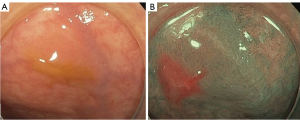

A 43-year-old patient was admitted to the hospital for screening gastroscopy and colonoscopy at their own request. The patient had no chronic diseases, and there was no evidence of a family history or allergies. Physical examination results were unremarkable. Colonoscopy revealed an oval neoplasm measuring up to 3 mm × 2 mm with a smooth surface and no capillary pattern in the distal third of the sigmoid colon (Figure 1A,1B). Cold snare polypectomy within healthy tissue was performed without postoperative complications (Video 1). The patient was discharged with recommendations for follow-up.

Examination of the biopsy specimen revealed fragments of mucosa with a smooth surface and uniform distribution of crypts. The resection margins were negative. The upper layers of the mucosal lamina propria contained proliferating cells with morphologic characteristics indicating a perineural origin. The cells had elongated spindle-shaped nuclei with pointed ends; the cytoplasm was slightly eosinophilic and lacked clear borders, forming short, barely visible multidirectional bundles. The density and composition of the lamina propria cellular infiltrate were within normal limits. The epithelium covering the lesion area appeared somewhat flattened, with no alterations in the crypt epithelium. Immunohistochemical examination showed diffuse positive nuclear and cytoplasmic staining of tumor cells for S100 (Figure 2A,2B). Perineuroma was ruled out as the tumor cells did not react positively with EMA staining, confirming the diagnosis of mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma. At the one-year follow-up colonoscopy, the mucosa in the distal third of the sigmoid colon showed localized postoperative scar changes without evidence of residual neoplasia.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

The term “Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma” was coined by Gibson et al. in their landmark 2009 paper identifying “26 Neural Colon Polyps Distinct From Neurofibromas and Mucosal Neuromas” (1). MSCHs are benign tumors of neurogenic origin, typically observed during screening colonoscopies as sessile polyps that are often, but not always, solitary. These polyps do not have any association with hereditary syndromes, although MSCHs have been observed in patients with ulcerative colitis (2,3,10).

Furthermore, endosonography results indicate that the pathological process demonstrates homogeneous hypoechogenicity and is confined to the superficial layers of the mucosa (2). MSCHs are frequently found in the distal parts of the colon and are less commonly located in the gallbladder, duodenum, esophageal-gastric junction, and stomach (4-8). The differential diagnosis for neurogenic tumors in the colon includes mucosal neuroma, which is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B (MEN 2B), neurofibroma linked to neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), schwannoma, ganglioneuroma, intramucosal perineuroma, and mucosal benign epithelioid nerve sheath tumor. Immunohistochemical analysis typically reveals Schwann cells positive for S-100 protein, negative for neurofilament protein (NFP), and without staining for CD34, smooth muscle actin (2). In practice, a number of features are also utilized to exclude other lesions that may microscopically resemble MSCH, such as neurofibroma (e.g., the absence of clinical signs and the lack of fibroblasts or perineural cells in histopathology), schwannoma (e.g., absence of collagenous stroma or specific patterns related to Antoni A and B), and especially GIST, which may present with spindle-shaped cells and positive S100 protein, but also show positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 and C-kit/CD117 (2).

The cause of MSCH is poorly understood. The diverse distribution of MSCHs in various anatomic locations may suggest that they develop as a response to ongoing damage to the mucosa (2). Clinical presentation of MSCH may range from asymptomatic to pain with hematochezia. Regular follow-up is recommended as prognostic factors are still being studied. Less than 100 cases have been described in the literature (11).

Currently, due to the rarity of these types of unusual polyps, there is insufficient data on treatment outcomes and monitoring recommendations. This is why we aim to contribute additional information to raise awareness.

These polyps are not associated with an inherited syndrome and present no risk of malignancy (1,7). Considering the superficial location of the neoplasm in the lamina propria of the gastrointestinal tract, it can be removed using the cold snare polypectomy technique. Therefore, according to the literature, a follow-up colonoscopy is unnecessary (1,7). In our view, a follow-up colonoscopy is not required if the margins of resection are negative based on morphological examination.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1597/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gibson JA, Hornick JL. Mucosal Schwann cell "hamartoma": clinicopathologic study of 26 neural colorectal polyps distinct from neurofibromas and mucosal neuromas. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:781-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okamoto T, Yoshimoto T, Fukuda K. Multiple non-polypoid mucosal Schwann cell hamartomas presenting as edematous and submucosal tumor-like lesions: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 2021;21:29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bae JM, Lee JY, Cho J, Lim SA, Kang GH. Synchronous mucosal Schwann-cell hamartomas in a young adult suggestive of mucosal Schwann-cell harmatomatosis: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 2015;15:128. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ismael F, Khawar S, Hamza A. Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma of the gallbladder. Autops Case Rep 2021;11:e2021338. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khanna G, Ghosh S, Barwad A, Yadav R, Das P. Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma of gall bladder: a novel observation. Pathology 2018;50:480-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oguntuyo KY, Donnangelo LL, Zhu G, Ward S, Bhattacharaya A. A Rare Case of Schwann Cell Hamartoma in the Duodenum. ACG Case Rep J 2022;9:e00894. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Beizai P, Russell JW, Westbrook L, Nowain A, Wang HL. Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma of the gastroesophageal junction: A series of 6 cases and comparison with colorectal counterpart. Ann Diagn Pathol 2020;47:151531. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hytiroglou P, Petrakis G, Tsimoyiannis EC. Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma can occur in the stomach and must be distinguished from other spindle cell lesions. Pathol Int 2016;66:242-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chintanaboina J, Clarke K. Case of colonic mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma and review of literature on unusual colonic polyps. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr-2018-224931. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neis B, Hart P, Chandran V, Kane S. Mucosal schwann cell hamartoma of the colon in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9:183-5.

- Mauriz Barreiro V, Ramos Alonso M, Fernández López M, Rivera Castillo DA, Durana Tonder C, Pradera Cibreiro C. Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma: a benign and little-known entity. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2024;116:223-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]