Improved prostate cancer diagnosis: upgraded prostate imaging reporting and data system (PI-RADS) scores by zoomed diffusion-weighted imaging enhance deep-learning-based computer-aided diagnosis accuracy

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a crucial tool for diagnosing and stratifying the risk of prostate cancer (PCa) due to its non-invasiveness, accuracy, and comprehensiveness (1). The integration of artificial intelligence algorithms has facilitated the development of deep-learning-based computer-aided diagnosis (DL-CAD) systems using MRI images to assist in detecting PCa. Research has demonstrated that deep-learning models enhance the performance and reproducibility of diagnosis, particularly for radiologists with limited or intermediate experience (2-5). The prostate imaging reporting and data system (PI-RADS) scores play a pivotal role in diagnostic performance (6). Accurate PI-RADS scores for suspected lesions provide valuable information for clinicians, aiding in risk assessment and informing decisions regarding biopsy and early surgical intervention.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is a key component of MRI and provides qualitative and quantitative information on detected lesions (6,7). Studies have shown a direct correlation between apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values derived from DWI and tumor aggressiveness (6,8,9). The image quality of DWI significantly impacts the diagnostic performance of DL-CAD (10,11). Conventional full-field-of-view single-shot echo-planar DWI (f-DWI), constrained by distortions, susceptibility artifacts, and spatial resolution, leads to a low true positive rate and ambiguous PI-RADS scores in DL-CAD detection (12). In contrast, the recently developed zoomed-field-of-view echo-planar DWI (z-DWI), utilizing a rotating field of excitation, complex averaging, and motion compensation, has been proposed to reduce geometric distortions and susceptibility artifacts and to achieve higher spatial resolution (13,14). z-DWI has demonstrated potential in enhancing the diagnostic performance of radiomic models and radiologists without computer-aided diagnosis (13,15,16). A prior study revealed that z-DWI improved PCa detection in MRI-based DL-CAD, attributed to its lower ADC values, higher signal-to-noise ratio, and higher contrast-to-noise ratio compared with conventional DWI techniques (17). Nonetheless, the diagnostic performance of radiologists using DL-CAD and their corresponding PI-RADS scores when using different DWI techniques has not been comprehensively analyzed.

Therefore, this study aims to compare the diagnostic performance and PI-RADS scores of DL-CAD in PCa detection using conventional f-DWI and advanced z-DWI and to extend this comparison to radiological clinical practice, in which radiologists use DL-CAD. We present this article in accordance with the STARD reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1263/rc).

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This retrospective study was approved by the local ethics committee at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine [approval No. 2022-KY-073 (K)-(1)]. This study expands upon the prior prospective studies that aimed to enhance the diagnostic ability of DL-CAD system for PCa. All patients provided informed consent before MRI scans and consented to the anonymized storage of their data to facilitate future studies.

Study population

There were 359 patients who underwent MRI examinations and subsequent biopsies due to clinically suspected PCa at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine between September 2019 and January 2021 included in the study. Biopsies encompassed ultrasound-guided-targeted biopsies, which involved the extraction of 2–4 cores from lesions deemed suspicious (PI-RADS ≥3), as well as systematic biopsies, consisting of 10–12 cores taken for comprehensive analysis. In total, 496 lesions were identified, among which 253 (51%) were malignant.

The inclusion criteria for the study population were as follows: (I) complete MRI sequences, including at least T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), f-DWI, and z-DWI; (II) comprehensive biopsy results, including the location and Gleason score (GS) for PCa; and (III) full clinical information. Exclusion criteria encompassed: (I) severe artifacts on MRI images; (II) history of PCa treatment, such as antihormonal, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy; (III) biopsy conducted within a 6-month period preceding the MRI examination; (IV) a gap ≥2 weeks between MRI examination and biopsy procedures. Twenty-eight men were excluded based on exclusion criteria, as shown in Figure 1. Detailed characteristics of participants and lesions are provided in Tables 1,2.

Table 1

| Variables | Patients without PCa (n=183) | Patients with PCa (n=176) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 (65–75) | 72 (66–78) | 0.001* |

| Total PSA (ng/mL) | 8.9 (5.1–13.1) | 13.9 (6.7–32.0) | <0.001* |

| Free PSA (ng/mL) | 1.32 (0.8–2.3) | 1.57 (0.8–3.6) | 0.053 |

| Free PSA/total PSA | 0.17 (0.13–0.22) | 0.11 (0.07–0.16) | <0.001* |

| No. of patients with MRI-detected lesions | – | ||

| 1 lesion | 153 [84] | 113 [64] | |

| 2 lesions | 17 [9] | 53 [30] | |

| 3 lesions | 7 [4] | 8 [5] | |

| More than 3 lesions | 6 [3] | 2 [1] | |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n [%]. *, statistically significant. PCa, prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 2

| Variables | Benign lesions (n=243) | PCa lesions (n=253) |

|---|---|---|

| Lesion location | ||

| Transition zone | 169 [70] | 117 [46] |

| Peripheral zone | 74 [30] | 136 [54] |

| GGG | ||

| GGG 1 (GS 3+3) | NA | 18 [7] |

| GGG 2 (GS 3+4) | NA | 34 [13] |

| GGG 3 (GS 4+3) | NA | 82 [32] |

| GGG 4 (GS =8) | NA | 41 [17] |

| GGG 5 (GS >8) | NA | 78 [31] |

Data are presented as n [%]. PCa, prostate cancer; GGG, Gleason grade group; NA, not applicable; GS, Gleason score.

MRI

MRI images were obtained using a 3-T MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a phased-array 18-channel body coil and an integrated 32-channel spine coil for signal acquisition. The scan protocol for all patients included T2WI, f-DWI, and z-DWI, with b values of 50, 1,000, and 1,500 s/mm2, respectively. f-DWI was conducted using a single-shot echo-planar imaging sequence, while z-DWI employed a research zoomed field-of-view echo-planar imaging sequence with a rotating field of excitation (18), complex averaging (19), and motion compensation (20). Detailed parameters of institutional prostate MRI sequences are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3

| Sequence parameters | T2WI | f-DWI | z-DWI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Turbo spin echo | SS-EPI | Zoomed SS-EPI |

| FOV (mm2) | 200×200 | 380×280 | 190×109 |

| Matrix | 320×256 | 178×132 | 100×56 |

| Voxel size (mm3) | 0.6×0.6×3.5 | 2.1×2.1×3.0 | 1.9×1.9×3.0 |

| Echo time (ms) | 101 | 79 | 76 |

| Repetition time (ms) | 6,000 | 4,200 | 3,800 |

| Phase-encoding direction | L-R | A-P | L-R |

| b-value (s/mm2) | NA | 50, 1,000, 1,500 | 50, 1,000, 1,500 |

| Bandwidth (Hz/px) | 200 | 1,870 | 1,612 |

| Fat suppression | NA | FatSat | FatSat |

| Number of excitation | 2 | 1, 3, 6 | 1, 3, 6 |

| Acceleration factor | 2 (GRAPPA) | 2 (GRAPPA) | NA |

| Acquisition time (min:s) | 2:08 | 3:05 | 2:37 |

This table is adapted from Tab. 1 by Hu et al. (17), used under CC BY 4.0. Permission file is not needed under an open access Creative Commons CC BY license. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T2WI, T2-weighted imaging; f-DWI, full-field-of-view single-shot echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging; z-DWI, zoomed-field-of-view echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging; SS-EPI, single-shot echo-planar imaging; FOV, field of view; L-R, left-right; A-P, anterior-posterior; NA, not applicable; GRAPPA, generalized autocalibrating partial parallel acquisition.

Ground truth and image annotation

The nature of lesions was confirmed through pathologic results from the biopsy. Lesions were precisely localized using the prostate’s sextant scheme, which entailed dividing the prostate contours into six segments along the midsagittal plane and four additional angulated planes (21,22). A genitourinary pathologist with 20 years of experience, blinding to all clinical information, such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA), reviewed all biopsies and established pathologic sextants for cancer areas, documenting GS for all cancer foci. Subsequently, a genitourinary radiologist with 20 years of experience reviewed all the MRI images, creating T2WI sextants and visually aligning them with pathologic sextants in the lesion locations. Both experts held weekly discussions to ensure precise matching between MRI images and pathologic sections. The lesion location, pathologic results, and corresponding GS were recorded. International Society of Urological Pathology grade groups of 2 and higher (range, 1–5) were considered clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa) (23).

Deep-learning-based computer‑aided diagnosis

A research DL-CAD system (MR Prostate AI v1.2.5; October 2020; Siemens Healthineers) was used to evaluate the performance of z-DWI and f-DWI in detecting and classifying prostate lesions (24). The DL-CAD system was trained on T2WI and f-DWI images derived from 2,170 bp-MRI prostate examinations across 7 institutions, consisting of 944 cases without lesions and 1,226 cases with at least one clinically significant lesion, as indicated by a PI-RADS score ≥3. The 359 cases in this paper were not included in the training dataset.

The MRI images in this study were divided into two groups: T2WI + f-DWI and T2WI + z-DWI. Each group of images was uploaded separately to DL-CAD. DL-CAD then used the input data to generate ADC maps and DWI at b=2,000 s/mm2. Additionally, DL-CAD performed whole-gland segmentation on T2WI volumes and aligned synthetic DWI and ADC maps to the T2WI. The DL-CAD system automatically detected potential malignant lesions, providing lesion localizations and PI-RADS scores (3, 4, or 5) based on f-DWI and z-DWI, respectively. If the detected lesions were considered benign, DL-CAD would not display any results. In this study, the PI-RADS scores of benign lesions detected by DL-CAD were artificially assigned a score of 2.

Readers and image interpretation

Two genitourinary radiologists, with 3 and 8 years of experience, participated in the consensus reading of MRI images. They were tasked with using DL-CAD to assign PI-RADS scores (ranging from 1 to 5) to each lesion based on T2WI and f-DWI images. Subsequently, they were instructed to re-evaluate the T2WI and z-DWI images of all patients using DL-CAD after a 4-week interval. PI-RADS v2.1 was utilized for scoring (6). The two radiologists were blinded to all pathologic results and clinical information to ensure that the PI-RADS scores were solely based on radiological experience and DL-CAD output. In cases where the two radiologists could not reach a consensus on the score of a particular lesion, a third senior radiologist was consulted to make the final decision. A PI-RADS score was considered an upgrade when the following conditions were met: (I) malignant lesions confirmed by pathology; (II) under the same condition, the PI-RADS score of a lesion was higher when using z-DWI than that when using f-DWI; (III) the PI-RADS score based on z-DWI ≥3.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 23.0) and R statistical software (version 4.2.1; https://www.R-project.org/). The one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the data’s conformity to a normal distribution. The independent-sample t-test was applied to continuous data that exhibited normal distribution. The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to evaluate continuous variables that deviated from normal distribution, as well as categorical variables. The diagnostic performance based on different DWI techniques in detecting and classifying prostate lesions was evaluated using free-response receiver operating characteristics (FROC) and alternative free-response receiver operating characteristics (AFROC) analyses. The FROC and AFROC curves were plotted using the “BayesianFROC” packages. Interobserver agreement for PI-RADS scores was evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) statistics. The ICC values were interpreted as follows: 0–0.20 as slight, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41–0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as substantial, and 0.81–1 as almost perfect agreement. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the association between clinical factors, PI-RADS score upgrade, and the risk of csPCa. Multicollinearity among variables in the multivariable analysis was identified using a variance inflation factor threshold greater than 10. Results with P≤0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Patients and lesion characteristics

A total of 359 patients were included in the study, with a median age of 69 years (interquartile range, 65–75 years), and a total of 496 lesions (253 PCa lesions and 243 benign lesions) were identified. Patients with PCa were found to have a higher median age (72 vs. 69 years, P=0.001), an elevated level of total PSA (tPSA) (13.9 vs. 8.9 ng/mL, P<0.001), and a lower free/total PSA (f/t PSA) ratio (0.11 vs. 0.17 ng/mL, P<0.001) compared to those without PCa. No significant difference was found in free PSA level between the two groups (1.57 vs. 1.32, P=0.053).

The detailed clinical characteristics of participants, stratified by pathological results, are summarized in Table 1. Detailed information on lesions, including location and pathologic results, is shown in Table 2.

Diagnostic performance

The diagnostic performance of DL-CAD and radiologists using DL-CAD, based on z-DWI and f-DWI, respectively, is presented in Figure 2. The true positive and false positive detections of PCa lesions using different DWI techniques are summarized in Table 4. The diagnosis index of PCa lesions detection using different DWI techniques are summarized in Table 5.

Table 4

| PCa lesions detection | PI-RADS | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| True-positive lesions | ||||

| DL-CAD | 0.074 | |||

| f-DWI (n=189) | 19 | 42 | 128 | |

| z-DWI (n=227) | 18 | 73 | 136 | |

| Radiologists using DL-CAD | 0.004* | |||

| f-DWI (n=230) | 33 | 75 | 122 | |

| z-DWI (n=239) | 13 | 93 | 133 | |

| False-positive lesions | ||||

| DL-CAD | 0.58 | |||

| f-DWI (n=60) | 9 | 25 | 26 | |

| z-DWI (n=78) | 13 | 38 | 27 | |

| Radiologists using DL-CAD | 0.43 | |||

| f-DWI (n=54) | 35 | 11 | 8 | |

| z-DWI (n=56) | 30 | 17 | 9 | |

*, statistically significant. PCa, prostate cancer; DL-CAD, deep-learning-based computer-aided diagnosis; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; f-DWI, full-field-of-view single-shot echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging; z-DWI, zoomed-field-of-view echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging; PI-RADS, prostate imaging reporting and data system; FPR, false positive rate; FNR, false negative rate; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Table 5

| Mode | MRI sequence | FPR | FNR | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL-CAD | f-DWI | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 0.74 |

| z-DWI | 0.32 | 0.1 | 0.74 | 0.86 | |

| Radiologists using DL-CAD | f-DWI | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| z-DWI | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.93 |

DL-CAD, deep-learning-based computer-aided diagnosis; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; f-DWI, full-field-of-view single-shot echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging; z-DWI, zoomed-field-of-view echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging; FPR, false positive rate; FNR, false negative rate; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

In comparison to f-DWI, z-DWI enables DL-CAD to demonstrate a lower false positives number per patient at the same sensitivity and to exhibit better diagnostic performance in detecting PCa lesions {area under the curve (AUC), 0.857 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.842–0.870] vs. 0.841 (95% CI: 0.824–0.856); P=0.02} (Figure 2A,2B). There was no statistical difference in true positive and false positive detections between DL-CAD based on f-DWI and z-DWI, respectively (both P>0.05).

When radiologists use DL-CAD, z-DWI enables radiologists to demonstrate a lower false positives number per patient at the same sensitivity compared with f-DWI (Figure 2C). A statistically significant difference was found in true positive detections (P=0.004) but not in false positive detections (P=0.43) between f-DWI and z-DWI. However, the usage of z-DWI did not significantly increase the diagnostic performance of radiologists [AUC, 0.887 (95% CI: 0.873–0.901) vs. 0.881 (95% CI: 0.864–0.895); P=0.16] (Figure 2D).

PI-RADS scores analysis

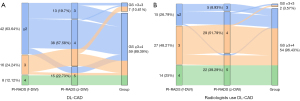

Table 6 shows the number of detected PCa lesions with upgraded PI-RADS scores and the proportion of csPCa among them, categorized by location. The changes in PI-RADS scores of PCa lesions after applying z-DWI are depicted in Figure 3. Corresponding examples with upgraded scores are presented in Figure 4.

Table 6

| PI-RADS scores change | DL-CAD | Radiologists using DL-CAD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCa, n | csPCa, n | csPCa (%) | PCa, n | csPCa, n | csPCa (%) | ||

| ≤2 upgraded to 3/4/5 | 42 [18, 24] | 39 [17, 22] | 93 | 15 [7, 8] | 14 [6, 8] | 93 | |

| 3 upgraded to 4 | 14 [3, 11] | 10 [1, 9] | 71 | 20 [5, 15] | 19 [5, 14] | 95 | |

| 3 upgraded to 5 | 2 [1, 1] | 2 [1, 1] | 100 | 7 [3, 4] | 7 [3, 4] | 100 | |

| 4 upgraded to 5 | 8 [6, 2] | 8 [6, 2] | 100 | 14 [0, 14] | 14 [0, 14] | 100 | |

| Total | 66 [30, 36] | 59 [25, 34] | 89 | 56 [15, 41] | 54 [14, 40] | 96 | |

Data in square brackets are numbers of PCa located in TZ and PZ, respectively. PCa, prostate cancer; csPCa, clinically significant prostate cancer; PI-RADS, prostate imaging reporting and data system; DL-CAD, deep-learning-based computer-aided diagnosis; TZ, transition zone; PZ, peripheral zone.

In comparison to f-DWI, z-DWI enables DL-CAD to yield a higher mean PI-RADS score for PCa lesions (4.26 vs. 3.92; P<0.001). A substantial agreement was found between DL-CAD assessments using f-DWI and z-DWI (0.653, 0.600–0.701; P<0.001). Employing z-DWI led to an upgrade in PI-RADS scores for 66 PCa lesions compared to f-DWI. Specifically, the scores of 42 lesions were upgraded from ≤2 to ≥3, 16 lesions were upgraded from 3 to ≥4, and 8 lesions were upgraded from 4 to 5. The csPCa accounts for 89% (59/66) of PCa lesions with upgraded PI-RADS scores.

When radiologists use DL-CAD, using z-DWI also led to a higher mean PI-RADS score for PCa lesions (4.31 vs. 4.02; P<0.001) compared to f-DWI. A substantial agreement was found among radiologists using DL-CAD based on different DWI techniques (0.742, 0.699–0.779; P<0.001). Employing z-DWI led to an upgrade in PI-RADS scores for 56 PCa lesions compared to f-DWI. Specifically, the scores of 15 lesions were upgraded from ≤2 to ≥3, 27 lesions were upgraded from 3 to ≥4, and 14 lesions were upgraded from 4 to 5. The csPCa accounts for 96% (54/56) of PCa lesions with upgraded PI-RADS scores. The upgrade for the 14 PCa lesions of 4-score was due to manual measurements showing maximum diameters of ≥1.5 cm in z-DWI/ADC, in contrast to that of <1.5 cm in f-DWI/ADC. No extracapsular tumor extension was newly identified in radiologists using DL-CAD with z-DWI.

Risk factors evaluation

As shown in Figure 5, age, tPSA, f/t PSA, PI-RADS upgrade (DL-CAD) and PI-RADS upgrade (R + DL-CAD) were independent risk factors associated with csPCa [odds ratio (OR)age =1.033, 95% CI: 1.001–1.065, P=0.042; ORtPSA =1.035, 95% CI: 1.014–1.057, P=0.001; ORf/tPSA =4.521, 95% CI: 1.000–20.434, P=0.05; ORPI-RADS upgrade (DL-CAD) =7.307, 95% CI: 2.826–18.892, P<0.001; ORPI-RADS upgrade (R + DL-CAD) =18.781, 95% CI: 4.22–83.585, P<0.001].

Discussion

In this study, we compared the diagnostic performance and PI-RADS scores of DL-CAD based on advanced z-DWI and conventional f-DWI and extended this comparison to radiological clinical practice, in which radiologists use DL-CAD. In addition, we analyzed the relationship between clinical factors, PI-RADS upgrade, and the risk of csPCa. Our findings demonstrate that z-DWI enables DL-CAD to exhibit better diagnostic performance, with a higher mean PI-RADS score for PCa lesions, and improved scores of 66 PCa lesions compared to f-DWI. When radiologists use DL-CAD, z-DWI also enables radiologists to exhibit a higher mean PI-RADS score for PCa lesions with improved scores of 56 PCa lesions compared to f-DWI. However, employing z-DWI did not significantly increase the diagnostic performance of radiologists. Lastly, the PI-RADS score upgrade achieved by using z-DWI was significantly correlated with the risk of csPCa.

The foremost role of the PI-RADS scores in clinical practice is to establish a consistent correlation between MRI-detected lesions and csPCa identified through biopsy. The main challenge lies in improving PCa detection while reducing unnecessary biopsies, therefore, the precision of PI-RADS scores holds paramount significance in clinical practice. For PCa lesions, particularly those indicative of csPCa, a score of 4 or 5 can facilitate timely biopsy and subsequent treatment. Conversely, a score of 3 suggests a potentially malignant lesion, posing a major dilemma for clinical decision-making. A previous study reported that the overall PCa detection rate in the PI-RADS score 3 was about 35%, much lower than that of 4 and 5, 60% and 90%, respectively (25). It could be managed by follow-up MRI to avoid unnecessary biopsies and potential adverse effects (26). In our study, 75% (12/16) of the PCa lesions upgraded from PI-RADS 3 to 4/5 by DL-CAD using z-DWI were csPCa. This proportion increased to 96% (26/27) when combined with radiologists. Without the assistance of z-DWI, these csPCa lesions would have been classified as PI-RADS 3, potentially delaying the detection and biopsy until they progressed or metastasized.

It was reported that z-DWI is characterized by better image quality with less image deformation and artifacts compared to conventional DWI images. Previous studies have highlighted the advantages of z-DWI in PCa detection, attributed to its lower average ADC values, higher contrast-to-noise ratio, and improved signal-to-noise ratio for lesions compared to f-DWI (17,27,28). These advantages have been linked to the enhanced performance of radiologists, radiomic models, and deep-learning models in PCa detection (13,15,17,27,29). In contrast to previous research, our study compared the PI-RADS scores when using different DWI techniques and extended the comparison to radiological practice. Our findings indicate that employing z-DWI in deep learning models leads to higher PI-RADS scores for PCa lesions, a result also observed in the diagnoses made by radiologists using DL-CAD. Furthermore, PI-RADS upgrade is significantly associated with csPCa risk. This suggests that z-DWI is more sensitive to PCa lesions compared to f-DWI.

However, when radiologists use DL-CAD, no statistically significant difference in terms of diagnostic performance was observed between f-DWI and z-DWI. This may partly indicate the limited benefits that z-DWI offers to radiologists compared to f-DWI. A previous study by Brendle et al. (16) reported a similar finding, showing no significant difference in sensitivity, specificity, and AUC (all P>0.05) between radiologists using z-DWI and conventional DWI to evaluate PCa lesions by scoring all images. Additionally, the substantial experience of the radiologists and the consensus reading in our study may also contribute to this result. Hambrock et al. (30) previously reported that there was no substantial improvement in diagnostic performance between experienced observers with computer-aided detection and those without [0.91 (95% CI: 0.86–0.97) vs. 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85–0.93); P=0.17]. The improvement in diagnostic performance brought by CAD was mainly observed in inexperienced readers. However, it remains unclear whether z-DWI can enhance the diagnostic performance of less experienced radiologists when using DL-CAD, and further investigation is warranted in the future.

Moreover, another important finding should be noted. Employing z-DWI in DL-CAD was associated with a lower false negative rate (0.10 vs. 0.25) and a higher false positive rate (0.32 vs. 0.25) compared to f-DWI. In other words, z-DWI decreased the rate of missed PCa diagnoses while simultaneously increasing the likelihood of performing unnecessary biopsies. After extending the comparison to radiological practice, the pattern persisted, albeit with a notably reduced gap in false negative rate (0.06 vs. 0.09), as well as in false positive rate (z-DWI vs. f-DWI, 0.23 vs. 0.22). This trade-off can be attributed to z-DWI’s enhanced visualization of mild/moderate or heterogeneous hyperintense and hypointense displayed by f-DWI. Although the diagnostic performance of radiologists using z-DWI and f-DWI showed no statistical difference (AUC, 0.887 vs. 0.881; P=0.16), z-DWI allowed for a higher negative predictive value (0.93 vs. 0.89) at the same positive predictive value compared to f-DWI. This indicates a subtle advantage of z-DWI in radiological practice. Furthermore, z-DWI also demonstrated a clearer delineation of lesion boundaries compared to f-DWI. Radiologists upgraded 14 csPCa lesions in the peripheral zone from score 4 to 5, as their maximum diameter in z-DWI/ADC exceeded 1.5 cm, contrasting with <1.5 cm in f-DWI/ADC. However, z-DWI did not show any superiority over f-DWI in identifying extracapsular tumor extension. In summary, we advocate employing both DWI techniques for scoring in radiological practice whenever z-DWI is accessible. Concordant scores from both enhance diagnostic reliability. In cases of discrepancies, z-DWI scores can be prioritized due to their lower false negative rate and higher negative predictive value, leading to reduced missed diagnoses and increased confidence in ruling out PCa.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this is a retrospective analysis, and all MRI scans were obtained using a single scanner from one manufacturer with identical imaging parameters in a single medical center. Additionally, the training sample volume in DL-CAD is not so large, and the DL-CAD system was trained with f-DWI images, therefore, whether the results are affected by lacking training for z-DWI remains unclear. Lastly, while systematic transrectal ultrasound-guided combined with targeted biopsy has shown high sensitivity and accuracy for PCa detection, there is still the possibility that certain lesions could be missed compared to radical prostatectomy specimens. If these lesions were detectable in DL-CAD, it could potentially increase the false positive rate. In future research, it will be important to validate these findings in a prospective and multi-center study.

Conclusions

z-DWI, in comparison to f-DWI, enhances the diagnostic performance of DL-CAD for PCa, assigning higher PI-RADS scores to malignant lesions. Despite offering limited improvement for radiologists using DL-CAD, z-DWI shows promise in enhancing the detection of csPCa.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STARD reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1263/rc

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1263/coif). C.F., Y.L., and C.X. are MR collaborating scientists from Siemens Shenzhen Magnetic Resonance Ltd., Siemens Healthcare, and Siemens Digital Medical Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., respectively, providing technical support for the DL-CAD system under Siemens collaboration regulations. Z.H. and L.W. are MR collaborating scientists from Siemens Shanghai Medical Equipment Ltd., providing technical support for the DL-CAD system under Siemens collaboration regulations. Z.X. is a collaborating scientist from Siemens Healthineers, providing technical support under Siemens collaboration regulations. R.G., H.v.B., T.B., A.K., and B.L. are developers from Siemens Healthineers and are responsible for developing the DL-CAD system. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This retrospective study was approved by the local ethics committee at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine [approval No. 2022-KY-073 (K)-(

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2020 Update. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur Urol 2021;79:243-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Youn SY, Choi MH, Kim DH, Lee YJ, Huisman H, Johnson E, Penzkofer T, Shabunin I, Winkel DJ, Xing P, Szolar D, Grimm R, von Busch H, Son Y, Lou B, Kamen A. Detection and PI-RADS classification of focal lesions in prostate MRI: Performance comparison between a deep learning-based algorithm (DLA) and radiologists with various levels of experience. Eur J Radiol 2021;142:109894. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Labus S, Altmann MM, Huisman H, Tong A, Penzkofer T, Choi MH, Shabunin I, Winkel DJ, Xing P, Szolar DH, Shea SM, Grimm R, von Busch H, Kamen A, Herold T, Baumann C. A concurrent, deep learning-based computer-aided detection system for prostate multiparametric MRI: a performance study involving experienced and less-experienced radiologists. Eur Radiol 2023;33:64-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rouvière O, Jaouen T, Baseilhac P, Benomar ML, Escande R, Crouzet S, Souchon R. Artificial intelligence algorithms aimed at characterizing or detecting prostate cancer on MRI: How accurate are they when tested on independent cohorts? - A systematic review. Diagn Interv Imaging 2023;104:221-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Twilt JJ, van Leeuwen KG, Huisman HJ, Fütterer JJ, de Rooij M. Artificial Intelligence Based Algorithms for Prostate Cancer Classification and Detection on Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:959. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turkbey B, Rosenkrantz AB, Haider MA, Padhani AR, Villeirs G, Macura KJ, Tempany CM, Choyke PL, Cornud F, Margolis DJ, Thoeny HC, Verma S, Barentsz J, Weinreb JC. Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2.1: 2019 Update of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2. Eur Urol 2019;76:340-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiavina R, Chessa F, Borghesi M, Gaudiano C, Bianchi L, Corcioni B, Castellucci P, Ceci F, Ceravolo I, Barchetti G, Del Monte M, Campa R, Catalano C, Panebianco V, Nanni C, Fanti S, Minervini A, Porreca A, Brunocilla E. State-of-the-art imaging techniques in the management of preoperative staging and re-staging of prostate cancer. Int J Urol 2019;26:18-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vargas HA, Akin O, Franiel T, Mazaheri Y, Zheng J, Moskowitz C, Udo K, Eastham J, Hricak H. Diffusion-weighted endorectal MR imaging at 3 T for prostate cancer: tumor detection and assessment of aggressiveness. Radiology 2011;259:775-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hötker AM, Mazaheri Y, Aras Ö, Zheng J, Moskowitz CS, Gondo T, Matsumoto K, Hricak H, Akin O. Assessment of Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness by Use of the Combination of Quantitative DWI and Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;206:756-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirano H, Minagi A, Takemoto K. Universal adversarial attacks on deep neural networks for medical image classification. BMC Med Imaging 2021;21:9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allyn J, Allou N, Vidal C, Renou A, Ferdynus C. Adversarial attack on deep learning-based dermatoscopic image recognition systems: Risk of misdiagnosis due to undetectable image perturbations. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e23568. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kozlowski P, Chang SD, Goldenberg SL. Diffusion-weighted MRI in prostate cancer -- comparison between single-shot fast spin echo and echo planar imaging sequences. Magn Reson Imaging 2008;26:72-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu L, Wei L, Wang S, Fu C, Benker T, Zhao J. Better lesion conspicuity translates into improved prostate cancer detection: comparison of non-parallel-transmission-zoomed-DWI with conventional-DWI. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021;46:5659-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Attenberger UI, Rathmann N, Sertdemir M, Riffel P, Weidner A, Kannengiesser S, Morelli JN, Schoenberg SO, Hausmann D. Small Field-of-view single-shot EPI-DWI of the prostate: Evaluation of spatially-tailored two-dimensional radiofrequency excitation pulses. Z Med Phys 2016;26:168-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu L, Zhou DW, Fu CX, Benkert T, Jiang CY, Li RT, Wei LM, Zhao JG. Advanced zoomed diffusion-weighted imaging vs. full-field-of-view diffusion-weighted imaging in prostate cancer detection: a radiomic features study. Eur Radiol 2021;31:1760-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brendle C, Martirosian P, Schwenzer NF, Kaufmann S, Kruck S, Kramer U, Notohamiprodjo M, Nikolaou K, Schraml C. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the assessment of prostate cancer: Comparison of zoomed imaging and conventional technique. Eur J Radiol 2016;85:893-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu L, Fu C, Song X, Grimm R, von Busch H, Benkert T, et al. Automated deep-learning system in the assessment of MRI-visible prostate cancer: comparison of advanced zoomed diffusion-weighted imaging and conventional technique. Cancer Imaging 2023;23:6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finsterbusch J. Improving the performance of diffusion-weighted inner field-of-view echo-planar imaging based on 2D-selective radiofrequency excitations by tilting the excitation plane. J Magn Reson Imaging 2012;35:984-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kordbacheh H, Seethamraju RT, Weiland E, Kiefer B, Nickel MD, Chulroek T, Cecconi M, Baliyan V, Harisinghani MG. Image quality and diagnostic accuracy of complex-averaged high b value images in diffusion-weighted MRI of prostate cancer. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:2244-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jolly MP, Guetter C, Guehring J. Cardiac segmentation in MR cine data using inverse consistent deformable registration. 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro. Rotterdam: IEEE; 2010:484-7.

- Hansen N, Patruno G, Wadhwa K, Gaziev G, Miano R, Barrett T, Gnanapragasam V, Doble A, Warren A, Bratt O, Kastner C. Magnetic Resonance and Ultrasound Image Fusion Supported Transperineal Prostate Biopsy Using the Ginsburg Protocol: Technique, Learning Points, and Biopsy Results. Eur Urol 2016;70:332-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuru TH, Wadhwa K, Chang RT, Echeverria LM, Roethke M, Polson A, Rottenberg G, Koo B, Lawrence EM, Seidenader J, Gnanapragasam V, Axell R, Roth W, Warren A, Doble A, Muir G, Popert R, Schlemmer HP, Hadaschik BA, Kastner C. Definitions of terms, processes and a minimum dataset for transperineal prostate biopsies: a standardization approach of the Ginsburg Study Group for Enhanced Prostate Diagnostics. BJU Int 2013;112:568-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B, Srigley JR, Humphrey PA. Grading Committee. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of Grading Patterns and Proposal for a New Grading System. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:244-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu X, Lou B, Shi B, Winkel D, Arrahmane N, Diallo M, Meng T, von Busch H, Grimm R, Kiefer B, Comaniciu D, Kamen A, Huisman H, Rosenkrantz A, Penzkofer T, Shabunin I, Choi MH, Yang Q, Szolar D. False Positive Reduction Using Multiscale Contextual Features for Prostate Cancer Detection in Multi-Parametric MRI Scans. 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). Iowa City, IA, USA: IEEE; 2020:1355-9.

- Venderink W, van Luijtelaar A, Bomers JGR, van der Leest M, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa C, Barentsz JO, Sedelaar JPM, Fütterer JJ. Results of Targeted Biopsy in Men with Magnetic Resonance Imaging Lesions Classified Equivocal, Likely or Highly Likely to Be Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 2018;73:353-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ullrich T, Quentin M, Arsov C, Schmaltz AK, Tschischka A, Laqua N, Hiester A, Blondin D, Rabenalt R, Albers P, Antoch G, Schimmöller L. Risk Stratification of Equivocal Lesions on Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Prostate. J Urol 2018;199:691-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma S, Xu K, Xie H, Wang H, Wang R, Zhang X, Wei J, Wang X. Diagnostic efficacy of b value (2000 s/mm(2)) diffusion-weighted imaging for prostate cancer: Comparison of a reduced field of view sequence and a conventional technique. Eur J Radiol 2018;107:125-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng Y, Li Z, Tang H, Wang Y, Hu X, Shen Y, Hu D. Comparison of reduced field-of-view diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and conventional DWI techniques in the assessment of rectal carcinoma at 3.0T: Image quality and histological T staging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018;47:967-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warndahl BA, Borisch EA, Kawashima A, Riederer SJ, Froemming AT. Conventional vs. reduced field of view diffusion weighted imaging of the prostate: Comparison of image quality, correlation with histology, and inter-reader agreement. Magn Reson Imaging 2018;47:67-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hambrock T, Vos PC, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa CA, Barentsz JO, Huisman HJ. Prostate cancer: computer-aided diagnosis with multiparametric 3-T MR imaging--effect on observer performance. Radiology 2013;266:521-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]