Clinical success and safety of N-butyl cyanoacrylate in emergency embolization: is operator experience a key factor?

Introduction

N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) is a synthetic biodegradable cyanoacrylate basis glue, modified by the addition of a monomer with adhesive, hemostatic, and antiseptic properties. It is commonly used in various clinical situations: portal embolization (1), varicocele embolization (2), pelvis insufficiency (3), and hemostasis transarterial embolization (TAE) (4-6). In emergency settings, NBCA can either be used for endovascular (7) or percutaneous approaches (8). NBCA is considered as difficult to use (9) and remains less popular than coils (10,11). The injection of NBCA/lipiodol mixture requires a steep learning curve to avoid non-target embolization. The liquid proprieties of NBCA provide several advantages in emergency settings, including its efficacy in small vessel occlusion (<1.5 mm), cases of coagulation disorders (12), and occlusion of target artery beyond the distal site of microcatheter advancement (7). Conducting comparative prospective studies of embolic agents is challenging in emergency settings. There are currently no prospective randomized trials comparing the clinical efficacy of one embolic agent to another. Previous studies have investigated the safety and efficacy profile in a particular location or a particular context. NBCA has proven to be efficient to treat peptic upper gastrointestinal ulcers (13), upper gastrointestinal bleeding (7), lower gastrointestinal bleeding (14), renal bleeding (12) and soft-tissue bleeding (15). These monocentric retrospective studies reported on the safety and efficacy of NBCA but included a limited number of patients. To our knowledge, the larger evaluation of NBCA efficacy is limited to one retrospective study in a tertiary center, including 104 patients (16). This study reported 76% clinical success and 21% 30-day mortality, without ischemic complications requiring further treatments. However, most of the procedures were performed by experienced interventional radiologists. Other retrospective studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety profile in real-life settings and on a larger scale.

This retrospective, single-centre study aimed to review our experience with TAE using NBCA as an embolic agent in a tertiary care setting. The objectives of the study were: (I) to assess the clinical outcomes and complications of TAE with NBCA in emergency situations, comparing results based on the operator’s experience; and (II) to evaluate the factors associated with early mortality following TAE with NBCA. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1767/rc).

Methods

Study population

All patients referred to University Hospital of Saint-Etienne and treated by TAE with NBCA between January 1, 2016 and January 1, 2024 were retrospectively reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: all patients ≥18 years old treated for non-cerebral bleeding by TAE in emergency settings with NBCA, alone or with another embolic agent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) patients treated by percutaneous approach; (II) patients <18 years old; (III) patients without long-term follow-up (i.e., follow-up <30 days); and (IV) no-available preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan. A study flow chart is detailed in Figure 1.

Clinical data

The following data were collected from electronic medical records. Patient demographics included age, gender, and comorbid conditions before TAE. Comorbid conditions included high blood pressure (HBP), ischemic cardiopathy, diabetes mellitus, anticoagulation or antiplatelet treatments. Biological data included hemoglobin level just before TAE, international normalized ratio (INR), transfusion requirements and the number of red blood cell (RBC) and platelet units transfused. Only the transfusions performed within the previous 24 hours or on the day of the embolization were taken into account. The etiology of bleeding was based on the clinical history and preoperative CT scan data. Hemodynamic instability was defined as a decrease in blood pressure requiring the use of amines.

Pre-procedure

All patients underwent an abdominal CT scan (SOMATOM DEFINITION AS 64, Siemens AG, Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany). Patients received ≥80 mL contrast medium (Xenetix 350, Guerbet, Villepinte, France) with a flow rate ≥3 mL/s. Unenhanced and contrast-enhanced CT of the interest region at the arterial (35 seconds) and portal phases (80 seconds) were performed according to the standard-of-care protocol of University Hospital of Saint-Etienne. Active bleeding was considered when iodine extravasation was present at the arterial phase and increased at portal phase. A pseudoaneurysm was considered as an enlargement of the arterial calibre, without an increase in size at the portal phase.

TAE methods and techniques

All TAEs were performed by one of the 10 interventional radiologists at the University Hospital of Saint-Etienne, whose experience ranged from 2 to 25 years, after multidisciplinary consultation (surgeon, anaesthetist, radiologist). The right common femoral artery was accessed routinely. Selective catheterization was performed to determine active bleeding using a 4F Cobra catheter (Glidecath, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and a hydrophilic guidewire (Terumo®, Tokyo, Japan). Superselective catheterization was systematically performed, using a 2.7-F Progreat®, microcatheter (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). TAE were performed using a NBCA (Glubran2®, GEM, Viareggio, Italy) Lipiodol® (Guerbet, Villepinte, France) mixture. After flushing the microcatheter with Glucose 5% in a 3-mL syringe, the NBCA/lipiodol mixture was made using 5 mL luer lock syringes and a 3-way tap, and then loaded into a 3-mL syringe. The mixture was then injected under fluoroscopic guidance. Once the mixture is injected, the microcatheter was removed approximately 30 seconds after the injection to prevent the mixture from adhering to the microcatheter. The ratio of NBCA/lipiodol depended on the distance between the tip of the microcatheter and the target, the location of the artery, the presence or absence of anastomosis, the diameter of the target artery, all of which were determined at the discretion of the interventional radiologist. In two situations, another embolic agent was used: either to limit the risk of non-target embolization when occluding gastroduodenal artery, or to occlude multiple target arteries during the same procedure. The choice of embolic agent, as well as the decision to use it was at the operator’s discretion. After the procedure, a complete angiogram using 4F catheters was performed to confirm that target artery and bleeding had been successfully controlled. No spasmolytic agents to reduce bowel peristalsis were administered, and no provocation test was conducted. Procedure data included documenting the embolized vessel, the embolic agent used, NBCA/lipiodol ratio, and the duration of the procedure. The duration of procedure was calculated based on the time of the first and last recorded images.

Patient follow-up

After TAE, all patients were closely monitored for clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of ischemic complication or recurrent bleeding until discharge or death.

Patients’ long-term outcomes, specifically incidence of rebleeding, mortality, and procedure-related complications were collected from patient charts. CT follow-up was not a routine practice performed following TAE in University Hospital of Saint-Etienne. Suspicion of rebleeding was based on acute decrease in hemoglobin levels. A rebleeding was confirmed if the hematoma had unequivocally increased in size on the CT scan and/or if active bleeding was visible on the CT scan and/or endoscopy. Ischemic complication was defined as necrosis of >25% of solid parenchymal tissue (kidney, liver, spleen) secondary to target or non-target embolization, or devascularization of a digestive wall diagnosed by imaging, endoscopy or surgery.

Definitions

Technical success was defined as the cessation of angiographic extravasation immediately after TAE based on angiographic findings. Clinical success was defined as the resolution of signs and symptoms of bleeding during the 30-day follow-up period after TAE and without endoscopic treatment, surgery, repeat TAE, or death of any cause. Clinical outcomes of procedures performed by operators with less than and more than 3 years of experience in TAE were evaluated. This 3-year period corresponds to the duration of the assistantship.

Complications were defined as per operative complications if they occurred during the TAE and post-operative complications if they occurred during the follow-up period. Rebleeding events were classified as early events if they occurred ≤3 days following TAE and as late events if they occurred >3 days following TAE. Minor and major complications were separated using the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE) classification (17), and complications scored ≥3 were considered as major complications. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the number of days from the procedure to the date of last news or death.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as medians and inter-quartiles for continuous variables and as numbers and frequencies for categorical variables. Odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed. A univariate and multivariate logistic regression model was used to explore the association between clinically relevant variables and early death. Multicollinearity among explanatory variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). All covariates had VIF values under 1.5, below the acceptable threshold (18). A comparison of OS regarding covariates subgroups was made using Kaplan-Meyers curves and log-rank test. Significance was considered for P<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software (version 8.4.2).

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethics board of University Hospital of Saint-Etienne (No. IRBN042024), and informed consent statement was obtained from all participants.

Results

Between January 1, 2016 and January 1, 2024, 122 patients underwent 122 procedures by TAE with NBCA in emergency settings in University Hospital of Saint-Etienne. A flowchart of the patient sample population is presented in Figure 1. Nine patients were excluded, leaving 113 patients included in the present study.

Patient characteristics

Detailed patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 64.1±14.1 years, including 75 (66.4%) males. Regarding previous treatments, 12 (10.6%) patients received antiplatelet therapy and 23 (20.4%) received anticoagulant therapy. There were 20 (17.8%) patients with active cancer, and 58 (51.3%) patients had HBP. The mean hemoglobin level was 9.11±2.0 g/dL, and 49 (43.4%) had hemodynamic instability before TAE. RBC and plasma transfusions were required in 73 (64.6%) and 38 (33.6%), respectively. The clinical characteristics did not significantly differ based on the operators’ experience (P>0.05).

Table 1

| Variables | Total | <3 years’ experience in TAE | ≥3 years’ experience in TAE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of procedures | 113 | 58 | 55 | – |

| Age (years) | 64.1±14.1 | 64.1±13.9 | 64.1±14.3 | 0.99 |

| Male | 75 (66.4) | 35 (65.5) | 40 (72.7) | 0.17 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 25 (22.1) | 15 (25.9) | 10 (18.2) | 0.43 |

| Coronaropathy | 33 (29.2) | 15 (25.9) | 18 (32.7) | 0.42 |

| HBP | 58 (51.3) | 30 (51.7) | 28 (50.9) | 0.93 |

| CKD | 13 (11.5) | 5 (8.6) | 8 (14.5) | 0.33 |

| Active cancer | 20 (17.7) | 11 (19.0) | 9 (16.4) | 0.72 |

| Anticoagulation therapy | 23 (20.4) | 12 (20.7) | 11 (20.0) | 0.93 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 12 (10.6) | 8 (13.8) | 4 (7.3) | 0.26 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Hemodynamic instability | 49 (43.4) | 22 (37.9) | 27 (49.1) | 0.24 |

| Melena | 11 (9.7) | 5 (8.6) | 6 (10.9) | 0.68 |

| Rectorragia | 4 (3.5) | 3 (5.2) | 1 (1.8) | 0.33 |

| Hematemesis | 10 (8.8) | 3 (5.2) | 7 (12.7) | 0.16 |

| Biology† | ||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 9.11±2.0 | 9.5±2.19 | 8.8±1.8 | 0.15 |

| INR | 1.19±0.28 | 1.32±0.24 | 1.30±0.32 | 0.79 |

| Pre-operative CT | ||||

| Active bleeding | 77 (68.1) | 36 (62.1) | 41 (74.5) | 0.16 |

| Number of pseudoaneurysm | 50 | 28 | 22 | |

| ≥1 pseudoaneurysm | 38 (33.6) | 25 (43.1) | 13 (23.6) | 0.03 |

| Number of pseudoaneurysm/patient | ||||

| 1 | 31 (81.6) | 23 (92.0) | 8 (61.5) | 0.51 |

| 2 | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | |

| 3 | 3 (7.9) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| 4 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Size of pseudoaneurysm (mm) | 18.4±12.7 | 20.1±14.3 | 16.2±10.4 | 0.51 |

| True aneurysm | 4 (3.5) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (5.4) | 0.29 |

| RBC transfusion | 73 (64.6) | 34 (58.6) | 39 (70.9) | 0.17 |

| Number of RBC units/patient | 4.18±2.25 | 4.94±2.56 | 3.51±1.94 | 0.05 |

| Plasma unit transfusion | 38 (33.6) | 22 (37.9) | 16 (29.0) | 0.32 |

| Number of plasma units/patient | 2.47±1.00 | 2.64±1.02 | 2.25±0.87 | 0.38 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, n (%) or n. †, data are missing for 10 patients. HBP, high blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; CT, computed tomography; RBC, red blood cell; TAE, transarterial embolization.

Imaging

All patients had a pre-operative angiographic CT. Active bleeding was detected in 77 (68.1%) patients and ≥1 pseudoaneurysm in 38 (33.6%) patients. The mean size of pseudoaneurysms was 18.4±12.7 mm. Four (3.5%) true aneurysms were detected included one renal artery aneurysm and 3 high-flow pancreaticoduodenal aneurysms related to a median arcuate ligament. Etiologies are detailed in Table 2. Main bleedings were related to blunt trauma [24 (21.2%)], iatrogenic origin [24 (21.2%)], spontaneous [21 (18.6%)], cancer [16 (14.1%)], and peptic gastroduodenal ulcers [12 (10.6%)].

Table 2

| Variables | Value (N=113) |

|---|---|

| Blunt trauma | 24 (21.2) |

| Iatrogenic | 24 (21.2) |

| Cephalic duodenopancreatectomy | 7 |

| Percutaneous renal biopsy | 3 |

| Sphincterotomy/biliary drainage | 3 |

| Drainage | 2 |

| Arterial puncture | 2 |

| Embolectomy | 1 |

| Partial nephrectomy | 1 |

| Adrenalectomy | 1 |

| Colonoscopy | 1 |

| Femoral prosthesis | 1 |

| Ureteral stent | 1 |

| Splenectomy | 1 |

| Spontaneous hematoma | 21 (18.6) |

| Cancer | 16 (14.1) |

| Hepatocarcinoma | 4 |

| Angiomyolipoma | 3 |

| Clear-cell carcinoma | 2 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2 |

| Rectum cancer | 1 |

| NET liver metastases | 1 |

| Gastric cancer | 1 |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 1 |

| Sarcoma | 1 |

| Peptic gastroduodenal ulcer | 12 (10.6) |

| Pancreatitis | 6 (5.3) |

| Median arcuate ligament | 3 (2.7) |

| Infection | 3 (2.7) |

| Diverticulosis | 1 (0.9) |

| Hydatidiform mole | 1 (0.9) |

| Aneurismal rupture | 1 (0.9) |

| Idiopathic | 1 (0.9) |

Data are presented as n (%) or n. NET, neuroendocrine tumor.

Procedure data

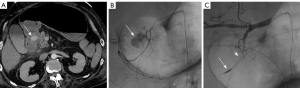

Regarding the 113 procedures, 58 (51.3%) were performed by operators with <3 years’ experience and 55 (48.7%) by operators with ≥3 years’ experience. Ninety-four (83.2%) patients were treated with NBCA alone and 19 (16.8%) patients were treated with another embolic agent, including coils (n=15) (Figure 2), gelatin sponge (n=2), microparticles (n=1) and plug (n=1). Technical success was achieved in all patients. The main embolized artery were renal (n=25), upper mesenteric (n=16), lumbar (n=12), gastroduodenal (n=11) and splenic arteries (n=8). The mean size of target artery was 2.1±0.8 mm, including 28 (24.8%) <1.5 mm. The mean duration of the procedure was 47.8±22.4 minutes. Procedural data are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3

| Variables | Value (N=113) |

|---|---|

| Experience of interventional radiologists (years) | 2–25 |

| Arteries embolized | |

| Renal | 25 (22.1) |

| Upper mesenteric | 16 (14.2) |

| Lumbar | 12 (10.6) |

| Gastroduodenal | 11 (9.7) |

| Splenic | 8 (7.1) |

| Internal iliac branch | 7 (6.2) |

| Right hepatic | 6 (5.3) |

| Pancreaticoduodenal | 6 (5.3) |

| Deep femoral | 4 (3.5) |

| Left hepatic | 3 (2.6) |

| Epigastric | 3 (2.6) |

| Cervicovaginal | 2 (1.8) |

| Left gastric | 2 (1.8) |

| Dorsal pancreatic artery | 2 (1.8) |

| Right gastric | 1 (0.9) |

| Bronchial | 1 (0.9) |

| Intercostal | 1 (0.9) |

| Rectal | 1 (0.9) |

| Superficial femoral | 1 (0.9) |

| Uterine | 1 (0.9) |

| Embolic agents | |

| NBCA/lipiodol alone | 94 (83.2) |

| NBCA and other agent | 19 (16.8) |

| Coils | 15 (13.2) |

| Internal iliac branch | 3 |

| Gastroduodenal | 3 |

| Renal | 3 |

| Pancreaticoduodenal | 1 |

| Left hepatic | 1 |

| Epigastric | 1 |

| Splenic | 1 |

| Upper mesenteric | 1 |

| Cervicovaginal | 1 |

| Gelatin sponge | 2 (1.8) |

| Internal iliac branch | 1 |

| Lumbar | 1 |

| Microparticles | 1 (0.9) |

| Upper mesenteric | 1 |

| Plug | 1 (0.9) |

| Splenic | 1 |

| NBCA/lipiodol ratio | |

| 1/1 | 51 (45.1) |

| 1/2 | 17 (15.1) |

| 1/3 | 20 (17.7) |

| 1/4 | 5 (4.4) |

| 1/5 | 4 (3.5) |

| Not reported | 16 (14.2) |

| Size of target artery (mm) | 2.1±0.8 |

| Target artery <1.5 mm | 28 (24.8) |

| Duration of procedure (min) | 47.8±22.4 |

Data are presented as range, n (%), n or mean ± SD. NBCA, N-butyl cyanoacrylate; SD, standard deviation.

Clinical outcomes

The mean follow-up time was 9.5±2.9 months. During the follow-up period, 25 (22.1%) patients died, including 15 (13.3%) patients who died within 30 days following the procedure. Clinical success was achieved in 93 (82.3%) patients. The origins of the 15 early deaths were as follows: 4 blunt traumas, 2 pancreatic cancers, 3 spontaneous bleedings, 2 gastroduodenal ulcers, 3 iatrogenic bleedings (1 adrenalectomy, 1 embolectomy, 1 biliary drainage), and 1 acute pancreatitis.

Five patients (4.4%) had early recurrent bleeding. A patient treated for splenic bleeding presented with hemorrhagic shock 6 hours after distal TAE with NBCA/lipiodol mixture. The CT scan showed an increase in the size of the hemoperitoneum. The patient underwent emergency salvage splenectomy, which confirmed persistent active bleeding. Another patient with a retroperitoneal hematoma under anticoagulant therapy experienced a 3-point drop in hemoglobin the day after TAE with NBCA alone. The CT scan showed a significant increase in retroperitoneal hemorrhage without active bleeding. The patient was monitored without additional treatment and did not experience any further recurrence. Three patients underwent repeat TAE for early rebleeding. Among these patients, a 91-year-old female died from a peptic ulcer one week after the repeat TAE, despite 2 additional attempts of endoscopic hemostasis. The remaining two recurrences were successfully treated with repeat TAE: one with a gelatin sponge to treat recurrent retroperitoneal bleeding from another lumbar artery, and the other with 2 coils to treat recurrent gastric bleeding from a peptic gastroduodenal ulcer. Outcomes are detailed in Table 4. The clinical success, mortality during follow-up, day-30 mortality, complications and recurrence of bleeding were not significantly different based on the operators’ experience (P>0.05).

Table 4

| Variables | Total (N=113) | <3 years’ experience in TAE | ≥3 years’ experience in TAE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of procedures | 113 | 58 | 55 | |

| Technical success | 113 (100.0) | 58 (100.0) | 55 (100.0) | – |

| Clinical success | 93 (82.3) | 49 (84.5) | 44 (80.0) | 0.54 |

| Mortality during follow-up | 25 (22.1) | 12 (20.7) | 13 (23.6) | 0.14 |

| Day-30 mortality | 15 (13.3) | 5 (8.6) | 10 (18.2) | 0.71 |

| Etiology of early death | – | |||

| Blunt trauma | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| Spontaneous hematoma | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Iatrogenic | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Peptic gastroduodenal ulcer | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Duration of procedure (min) | 47.8±22.4 | 52.2±26.0 | 42.6±18.4 | 0.08 |

| Complications | 9 (8.0) | 4 (6.9) | 5 (9.1) | 0.94 |

| Per-operative complications | ||||

| Non-target embolization | 3 (2.7) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.53 |

| Post-operative complications | ||||

| Femoral pseudoaneurysm | 3 (2.7) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.53 |

| Post embolization syndrome | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | 0.97 |

| Renal ischaemia/arterial dissection | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.32 |

| CIRSE grading complication | ||||

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0.53 |

| 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0.95 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Recurrence of bleeding | ||||

| Early ≤3 days | 5 (4.4) | 3 (5.2) | 2 (3.6) | 0.69 |

| Delayed >3 days | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Management of recurrent bleeding | ||||

| Repeat TAE | 3 (2.7) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.53 |

| Monitoring | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.32 |

| Surgery | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.32 |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | 9.5±2.9 | 11.2±11.2 | 6.3±6.9 | 0.16 |

Data are presented as n (%), n or mean ± SD. CIRSE, Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe; TAE, transarterial embolization; SD, standard deviation.

In univariate analysis, hemodynamic instability [OR =25.2 (95% CI: 4.76–466.1), P<0.01], hemoglobin level <8 g/dL [OR =3.39 (95% CI: 1.11–11.70), P=0.04], INR >1.5 [OR =5.05 (95% CI: 1.54–16.59), P<0.01] and embolization of gastroduodenal artery [OR =4.73 (95% CI: 1.10–18.48), P=0.02] were associated with early death (Table 5 and Figure 3). In multivariate analysis, hemodynamic instability was independently associated with early death [OR =14.49 (95% CI: 2.33–282.1), P=0.01].

Table 5

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Demographics data | |||||

| Age >65 years | 3.40 (1.00–15.58) | 0.07 | – | – | |

| Male | 1.46 (0.46–5.58) | 0.54 | – | – | |

| Active cancer | 1.86 (0.47–6.26) | 0.26 | – | ||

| Iatrogenic origin | 0.97 (0.21–3.43) | 0.55 | – | – | |

| Hemodynamic instability | 25.2 (4.76–466.1) | <0.01* | 14.49 (2.33–282.1) | 0.01* | |

| Biological data | |||||

| INR >1.5 | 5.05 (1.54–16.59) | <0.01* | 1.96 (0.53–7.34) | 0.31 | |

| Hb <8 g/dL | 3.39 (1.11–11.70) | 0.04* | 1.39 (0.37–5.49) | 0.61 | |

| CT imaging data | |||||

| ≥1 pseudoaneurysm | 0.68 (0.18–2.2) | 0.62 | – | – | |

| Active bleeding on CT | 3.5 (0.89–22.9) | 0.11 | – | – | |

| TAE data | |||||

| Procedure duration >60 min | 1.28 (0.27–4.61) | 0.62 | – | – | |

| <3 years’ experience in TAE | 0.42 (0.12–1.29) | 0.14 | – | – | |

| Association with another embolic agent | 1.28 (0.27–4.61) | 0.72 | – | – | |

| Lumbar artery | 4.09 (0.97–15.45) | 0.05 | – | – | |

| Renal artery | 0.22 (0.01–1.19) | 0.15 | – | – | |

| Gastroduodenal artery | 4.73 (1.10–18.48) | 0.02* | 1.96 (0.41–8.81) | 0.38 | |

*, a statistically significant difference was considered for P<0.05. INR, international normalized ratio; Hb, hemoglobin; CT, computed tomography; TAE, transarterial embolization; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Complications

Minor complications were seen in 9 (8.0%) patients including 3 non-target embolizations, 1 renal dissection of renal artery, 2 cases of post-embolization syndrome requiring morphine intra-venous (IV) perfusion, and 3 femoral pseudoaneurysms at the puncture site. Non-target embolization involved gastro-duodenal artery (n=2) and splenic artery (n=1). These 3 non-target embolizations did not have any ischemic consequences or require further interventions. An arterial dissection of the renal artery during catheterization, followed by progressive renal atrophy, without any impact on renal function, was reported. No major complications were reported. Moreover, the complication rate did not significantly differ based on the operators’ experience (P>0.05).

Discussion

The present retrospective study reported on a large cohort of patients who were treated by TAE in emergency settings with NBCA alone or with another embolic agent. Results showed how this procedure had a satisfactory safety profile without major complications and a low rebleeding rate 5 (5.5%), despite a significant 13.3% mortality rate due to patients’ severity upon admission. Even though non-target embolizations were documented in 3 (2.6%) patients, no clinical consequences were revealed. Rebleeding rate, early deaths, and complications did not significantly differ based on the operators’ experience (P>0.05).

Moreover, the results of procedures performed by operators with less than 3 years of experience show no statistical difference in terms of early mortality and complication rates. This finding challenges the common belief about the difficulties of using this embolic agent, regarding non-target embolization. The rates of rebleeding and early mortality are relatively low in the present study compared with previous studies (15,19-22). However, the comparison remains limited due to the small number of patients and the predominance of renal embolizations (22.1%) compared to gastrointestinal bleedings and soft tissue hematomas, which are associated with a higher mortality rate (15,20-22). Therefore, further validation is needed before actively recommending the use of NBCA by less experienced operators based on the current findings. The use of standardized protocols and the supervision of younger operators appear to be essential to ensure technical success without complications, particularly to prevent any off-target embolization. The present study highlights the importance of the patient’s biological and hemodynamic parameters in the clinical outcomes following TAE, which is in line with previous literature (23). Abdulmalak et al. reported that systolic pressure <90 mmHg was associated with early death (P<0.01) (16). The INR may reflect the use of anticoagulants but also a disseminated intravascular coagulation, secondary to the bleeding. The importance of these biological and hemodynamic parameters suggests that the operator’s experience, location of the bleeding, patient age, and comorbidities have a less significant impact on the patient outcomes.

NBCA offers several advantages that enhance its utility across various clinical scenarios. NBCA is a liquid agent whose monomers polymerize upon contact with the blood, enables distal occlusion, even in cases of coagulation disorders. This thereby theoretically reduces radiation exposure and procedural time as compared to coils. A meta-analysis reported 33.8% of clinical failure in patients with coagulopathy treated for gastrointestinal bleeding with NBCA, lower than that reported for TAE in general (24,25). NBCA is suitable to occlude small diameter target arteries. It is worth noting that 28 (24.8%) patients had a target artery <1.5 mm. In such cases, coil packing is limited, as most coil manufacturers offer coils with a diameter ≥2 mm. Additionally, NBCA follow the direction of blood flow, allowing occlusion at distance from the microcatheter. This property is particularly useful in cases of failure to catheterise the target artery, and to achieve simultaneous backdoor/frontdoor occlusion of pseudoaneurysms. Additionally, by varying the ratio of NBCA/lipiodol, the viscosity of the mixture can be adapted according to vessel flow, vessel diameter, and existence of collaterals. In the present study, the NBCA/lipiodol dilution was low, with >40% procedures performed using a 1/1 ratio. A high NBCA/lipiodol (>1/3 ratio) dilution appears useful in case of failure to catheterise the target vessel, or when a large volume of mixture is needed to achieve occlusion. To inject precisely the desired amount of mixture, we do not perform a ‘sandwich’ injection (dextrose-Glubran2®/Lipiodol® mixture-dextrose). In other words, the dead space of the catheter is not flushed after the vascular occlusion is completed. However, this requires removing the microcatheter once the mixture has been injected. Glubran2® offers several advantages over Histoacryl® as an embolic agent. First, Glubran2® has a slower polymerization time in low dilution ratio (1/1–1/3), allowing for more controlled injections, which reduces the risk of catheter entrapment (26). This is particularly useful when precise delivery is required in delicate vascular areas. Additionally, Glubran2® is less exothermic during polymerization, minimizing thermal damage to surrounding tissues. It also has better adhesive properties to vessel walls, leading to more effective occlusion (27).

On the other hand, gelatin sponge is a temporary embolic agent that requires delicate handling to avoid non-target embolization. A high dilution mixture with iodine contrast is needed to avoid microcatheter occlusion, but this limits its occlusion property. Microparticles are effective in achieving tumor devascularisation but may not be suitable for occluding proximal vessels or pseudoaneurysms. Moreover, assessing the endpoint of occlusion with microparticles can be challenging (1). The use of microcoils alone has been associated with a higher rate of recurrence in patients treated for gastrointestinal bleeding (28). We used a combination of coils and NBCA, which was performed to occlude high flow vessels, such as the gastroduodenal artery. Microcoils allow to avoid non-target embolization of NBCA, and NBCA allows for immediate vessel occlusion. The use of new liquid agents with higher viscosity will likely overcome the difficulties of high-flow TAE in emergency settings (29).

Even though non-target embolization was recorded in 3 (2.6%) patients in the present study, there were no ischemic complications with a clinical impact after long-term follow-up (9.5±2.9 months). This is similar to the previous findings of Abdulmalak et al. (16) and Yamakado et al. (23). Bowel ischemic complications following the use of NBCA are rare but require some precautions. Occlusion of more than 3 vasa recta seems to be associated with a higher risk of ischemic complications (30). A recent meta-analysis reporting efficacy of TAE of lower gastrointestinal bleeding reported a higher ischemic complications in patients treated by NBCA vs. microcoils (9.7% vs. 4.0% respectively), despite a lower rebleeding rate (9.3% vs. 20.8% respectively) (19). This study reported only 3 surgeries/245 patients who underwent routine colonoscopy after TAE. Ischemic complication reported in earlier studies on gastrointestinal TAE appears to be greatly overestimated, although endoscopy is not routinely performed postoperatively. Ischemic complications related to NBCA are theoretically similar to those of other permanent embolic agents, with the risk depending mainly on the location of the bleeding. An exceptional case of skin necrosis has been described in a patient with TAE of a spontaneous anterior abdominal wall hematoma (31).

The present study has some limitations. This was a retrospective monocentric study, with biases inherent to this type of study. Additionally, NBCA was used with another embolic agent in 19/113 (16.8%) procedures, mainly with coils [15 (13.2%)], which limits the evaluation of the real benefit of NBCA. However, the primary use of the other embolic agent was to reduce the risk of non-target embolization, with glue being used as the main agent. There was no systematic scanning or endoscopic follow-up to assess ischaemic complications. However, the lack of systematic follow-up with CT scans or endoscopy is not specific to NBCA embolization. Moreover, performing systematic CT scans or endoscopic checks is not clinically relevant in the absence of clinical symptoms. The results of the multivariate analysis should be interpreted with caution due to the very wide CIs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study shows a good efficacy profile, a low rebleeding rate (4.4%) and no ischemic complication with clinical impact in patients treated for emergency TAE with NBCA alone or with another embolic agent. The operator’s experience has no impact on clinical outcomes. Its use in clinical practice should be further explored.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michal Deml for English proofreading.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1767/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1767/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethics board of University Hospital of Saint-Etienne (No. IRBN042024), and informed consent statement was obtained from all participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Guiu B, Bize P, Gunthern D, Demartines N, Halkic N, Denys A. Portal vein embolization before right hepatectomy: improved results using n-butyl-cyanoacrylate compared to microparticles plus coils. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2013;36:1306-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vanlangenhove P, De Keukeleire K, Everaert K, Van Maele G, Defreyne L. Efficacy and safety of two different n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylates for the embolization of varicoceles: a prospective, randomized, blinded study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012;35:598-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gong M, He X, Zhao B, Kong J, Gu J, Su H. Ovarian Vein Embolization With N-butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate Glubran-2(®) for the Treatment of Pelvic Venous Disorder. Front Surg 2021;8:760600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yata S, Ihaya T, Kaminou T, Hashimoto M, Ohuchi Y, Umekita Y, Ogawa T. Transcatheter arterial embolization of acute arterial bleeding in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24:422-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee CW, Liu KL, Wang HP, Chen SJ, Tsang YM, Liu HM. Transcatheter arterial embolization of acute upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2007;18:209-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hur S, Yoon CJ, Kang SG, Dixon R, Han HS, Yoon YS, Cho JY. Transcatheter arterial embolization of gastroduodenal artery stump pseudoaneurysms after pancreaticoduodenectomy: safety and efficacy of two embolization techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:294-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chevallier O, Comby PO, Guillen K, Pellegrinelli J, Mouillot T, Falvo N, Bardou M, Midulla M, Aho-Glélé S, Loffroy R. Efficacy, safety and outcomes of transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue for non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagn Interv Imaging 2021;102:479-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grange R, Chevalier-Meilland C, Le Roy B, Grange S. Delayed superior epigastric artery pseudoaneurysm following percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy: Treatment by percutaneous embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Radiol Case Rep 2021;16:1459-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valji K. Cyanoacrylates for embolization in gastrointestinal bleeding: how super is glue? J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014;25:20-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spiliopoulos S, Inchingolo R, Lucatelli P, Iezzi R, Diamantopoulos A, Posa A, Barry B, Ricci C, Cini M, Konstantos C, Palialexis K, Reppas L, Trikola A, Nardella M, Adam A, Brountzos E. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization for Bleeding Peptic Ulcers: A Multicenter Study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2018;41:1333-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fontana F, Piacentino F, Ossola C, Coppola A, Curti M, Macchi E, De Marchi G, Floridi C, Ierardi AM, Carrafiello G, Segato S, Carcano G, Venturini M. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization in Acute Non-Variceal Gastrointestinal Bleedings: A Ten-Year Single-Center Experience in 91 Patients and Review of the Literature. J Clin Med 2021;10:4979. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gong M, He X, Zhao B, Kong J, Gu J, Su H. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization with N-Butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate Glubran 2 for the Treatment of Acute Renal Hemorrhage Under Coagulopathic Conditions. Ann Vasc Surg 2022;86:358-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loffroy R, Desmyttere AS, Mouillot T, Pellegrinelli J, Facy O, Drouilllard A, Falvo N, Charles PE, Bardou M, Midulla M, Aho-Gléglé S, Chevallier O. Ten-year experience with arterial embolization for peptic ulcer bleeding: N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue versus other embolic agents. Eur Radiol 2021;31:3015-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hur S, Jae HJ, Lee M, Kim HC, Chung JW. Safety and efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a single-center experience with 112 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014;25:10-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grange R, Grange L, Chevalier C, Mayaud A, Villeneuve L, Boutet C, Grange S. Transarterial Embolization for Spontaneous Soft-Tissue Hematomas: Predictive Factors for Early Death. J Pers Med 2022;13:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdulmalak G, Chevallier O, Falvo N, Di Marco L, Bertaut A, Moulin B, Abi-Khalil C, Gehin S, Charles PE, Latournerie M, Midulla M, Loffroy R. Safety and efficacy of transcatheter embolization with Glubran(®)2 cyanoacrylate glue for acute arterial bleeding: a single-center experience with 104 patients. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018;43:723-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filippiadis DK, Binkert C, Pellerin O, Hoffmann RT, Krajina A, Pereira PL. Cirse Quality Assurance Document and Standards for Classification of Complications: The Cirse Classification System. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017;40:1141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Midi H, Sarkar SK, Rana S. Collinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression model. Journal of Interdisciplinary Mathematics 2010;13:253-67.

- Yu Q, Funaki B, Ahmed O. Twenty years of embolization for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis of rebleeding and ischaemia rates. Br J Radiol 2024;97:920-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barral M, Pellerin O, Tran VT, Gallix B, Boucher LM, Valenti D, Sapoval M, Soyer P, Dohan A. Predictors of Mortality from Spontaneous Soft-Tissue Hematomas in a Large Multicenter Cohort Who Underwent Percutaneous Transarterial Embolization. Radiology 2019;291:250-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dohan A, Sapoval M, Chousterman BG, di Primio M, Guerot E, Pellerin O. Spontaneous soft-tissue hemorrhage in anticoagulated patients: safety and efficacy of embolization. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;204:1303-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dohan A, Darnige L, Sapoval M, Pellerin O. Spontaneous soft tissue hematomas. Diagn Interv Imaging 2015;96:789-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamakado K, Nakatsuka A, Tanaka N, Takano K, Matsumura K, Takeda K. Transcatheter arterial embolization of ruptured pseudoaneurysms with coils and n-butyl cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2000;11:66-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loffroy R, Favelier S, Pottecher P, Estivalet L, Genson PY, Gehin S, Cercueil JP, Krausé D. Transcatheter arterial embolization for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Indications, techniques and outcomes. Diagn Interv Imaging 2015;96:731-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim PH, Tsauo J, Shin JH, Yun SC. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization of Gastrointestinal Bleeding with N-Butyl Cyanoacrylate: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Safety and Efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28:522-531.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuetting D, Kupczyk P, Dell T, Luetkens JA, Meyer C, Attenberger UI, Pieper CC. In Vitro Evaluation of Acrylic Adhesives in Lymphatic Fluids-Influence of Glue Type and Procedural Parameters. Biomedicines 2022;10:1195. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leonardi M, Barbara C, Simonetti L, Giardino R, Aldini NN, Fini M, Martini L, Masetti L, Joechler M, Roncaroli F. Glubran 2: a new acrylic glue for neuroradiological endovascular use. Experimental study on animals. Interv Neuroradiol 2002;8:245-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tipaldi MA, Orgera G, Krokidis M, Rebonato A, Maiettini D, Vagnarelli S, Ambrogi C, Rossi M. Trans Arterial Embolization of Non-variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Is the Use of Ethylene-Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer as Safe as Coils? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2018;41:1340-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pal K, Patel M, Chen SR, Odisio BC, Metwalli Z, Ahrar J, Irwin D, Sheth RA, Kuban JD. A Single-Center Experience with a Shear-Thinning Conformable Embolic. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2024;35:1215-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwon JH, Kim MD, Han K, Choi W, Kim YS, Lee J, Kim GM, Won JY, Lee DY. Transcatheter arterial embolisation for acute lower gastrointestinal haemorrhage: a single-centre study. Eur Radiol 2019;29:57-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Djaber S, Bohelay G, Moussa N, Déan C, Del Giudicce C, Sapoval M, Dohan A, Pellerin O. Cutaneous necrosis after embolization of spontaneous soft-tissue hematoma of the abdominal wall. Diagn Interv Imaging 2018;99:831-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]