Prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis in T1 breast cancer using diffuse optical tomography, strain elastography and molecular markers

Introduction

Axillary lymph node (ALN) status has a significant prognostic impact in breast cancer (BC) (1,2). The incidence of T1 BCs has markedly increased from 36% to 68% with the implementation of cancer screening programs (3). Evidence suggests that even small tumors can metastasize, indicating that metastatic ability is an inherent genetic trait (4). Approximately 27% of T1 BC is node positive (4). Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is widely performed to identify ALN status, especially in clinically node-negative BC (5). However, although SLNB is a minimally invasive procedure, some patients experience upper limb edema and pain, which also increases operative time and cost (6). In addition, a small percentage of patients have false-negative SLNB in BC (7). Therefore, preoperative non-invasive prediction of ALN status is of great significance for avoiding ineffective axillary surgery.

Studies have indicated that the pathological features (8) and imaging features (9,10) of primary tumors are helpful in evaluating the possibility of axillary lymph node metastasis (ALNM). The histological tumor size, grade, lymphovascular invasion, hormone receptor status, and Ki-67 expression are clinically validated parameters that serve as reliable predictors of ALNM. However, lymphovascular invasion can only be determined from postoperative surgical resection and thus cannot be applied as preoperative assessment. Two-dimensional ultrasonography is valuable for diagnosing ALN status. However, the morphological changes in the lymph nodes occur later than the pathological changes, which may lead to false-negative results (11). Radiological examinations are more sensitive in identifying ALNM; however, they have several limitations, including being time consuming, costly, inapplicability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to some patients, and ionizing radiation from computed tomography. Currently, there is still no completely satisfactory method for the preoperative prediction of ALN status in early BC.

ALNM is determined by complex bidirectional interactions between tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment (12). The Ki-67 protein reflects the proliferative ability of tumor cells, and higher Ki-67 expression is associated with a worse prognosis (13). Several studies have indicated that Ki-67 expression is an independent risk factor for ALNM in BC (14,15). Nonetheless, the predictive ability of a single factor for ALNM remains limited, particularly for T1 BC. Tumor angiogenesis, a pivotal factor in the tumor microenvironment, is also involved in tumor progression (16). Ultrasound-guided diffuse optical tomography (DOT) is a functional imaging technique. Its main functional parameter is the tumor total hemoglobin concentration (TTHC), which is obtained by emitting near-infrared light and quantitatively reflects the blood supply to the tumor. A previous study has found that high TTHC measured by the DOT system in breast lesions with ALNM (17).

Tumor stromal stiffness is another essential factor in the microenvironment and has been reported to correlate with tumor aggression, invasion, and metastasis (18,19), suggesting that tumor stiffness may be helpful in assessing ALNM. The strain ratio (SR), as measured by strain elastography (SE), is a semi-quantitative measurement that reflects the relative stiffness of the tumor. A previous study has shown that tumor SR was associated with ALN status in BC (20). In general, TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression have all been reported to be associated with ALNM in BC. However, relatively few studies have focused on T1 BC.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the significance of TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression in predicting ALN status in T1 BC. However, due to the inherent heterogeneity of BC, relying on a single factor may be insufficient to accurately reflect prognosis. Consequently, we sought to investigate the combined predictive utility of these indicators. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1664/rc).

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The ethics committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University approved the study (No. 2020PS748K). Informed consent was taken from all individual participants. The study enrolled consecutive female patients with breast lesions who underwent surgical resection between March 2012 and August 2012. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) single lesion suspected of BC on ultrasound; (II) lesions ≤2.00 cm in maximum diameter on ultrasound; (III) complete preoperative imaging assessment (DOT and SE); (IV) pathologic diagnosis of invasive BC; and (V) pathologic diagnosis of ALN. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) resection biopsy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy before ultrasound evaluation; (II) distant metastases, previous BC, or history of other malignant tumors; (III) unsatisfactory imaging quality; and (IV) benign breast lesions or carcinoma in situ. A total of 122 eligible patients were included in the analysis. The patient selection flowchart is shown in Figure 1. The patients were divided into two groups, namely ALN-positive and ALN-negative, based on the pathological results of the ALN.

Evaluation of TTHC and SR

Two radiologists, each with over 5 years of experience in breast imaging, conducted independent double-blind SE and ultrasound-guided DOT evaluations. The SE and DOT examinations and data analyses commenced with a training phase involving the examination of images from at least 20 cases.

Ultrasound-guided DOT was performed using the Optimus type II breast imaging system (XinAo-MDT Technology Corporation, Langfang, Hebei, China). It consists of routine ultrasound (Terason T3000, 7–12 MHz linear probe, Teratech, Burlington, MA, USA) and near-infrared optical tomography. The near-infrared wavelengths were 785 and 830 nm. First, the lesion was located by ultrasound. Briefly, DOT emitted near-infrared light to scan the lesion horizontally and vertically and then scanned the symmetric part of the contralateral breast. Second, the boundary of the lesion was traced, and the system automatically generated the optical parameters and optical function image. Further, tissue absorption and scattering at different depths were evaluated. The color and brightness in DOT images indicate different intensities of light absorption. Redder and brighter colors indicate greater photon absorption, higher hemoglobin concentration, and more tissue blood supply. Meanwhile, bluer and darker colors indicate lesser photon absorption, lower hemoglobin concentration, and lesser tissue blood supply. The data were measured four times and averaged.

Elastography was performed using HV-900 ultrasonography (Hitachi Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and a linear probe (6–13 MHz). B-mode breast ultrasound was performed to determine the lesion, and then the elastic imaging procedure was started. The elastography sampling frame included the lesion and surrounding tissues, with the depth ranging from the subcutaneous fat to the pectoral muscle and the width covering the entire examination range. SE images were obtained by compressing the breast gently and considered optimal when the quality indicator ranging from 3 to 4. The subcutaneous fat layer was a mixture of red and green, the gland was green or mainly green, and the muscle layer was blue. Region of interest (ROI) A was drawn on the lesion, and ROI B was drawn on subcutaneous fat tissue and exclude the lesion. The SR, defined as the fat-to-mass SR, was automatically calculated. All measurements were performed four times and averaged.

Pathology and immunohistochemistry

All lesions were surgically removed and analyzed by histological and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. Two pathologists independently reviewed each case, and disagreements were resolved by discussion to achieve consensus. Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor were considered positive when ≥1% of tumor cells showed nuclear staining (21). Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positivity was defined as the tumor cell membrane having (I) a score of 3+ on IHC staining or (II) 2+ on IHC staining and HER2 amplification on fluorescence in situ hybridization (22). For Ki-67 staining, tumor image areas were examined under ×400 magnification, and the proportion of positively stained nuclei was determined randomly for a minimum of 10 fields of view. High Ki-67 expression was defined as a nuclear staining of ≥20% (23). BC was classified as luminal A, luminal B, HER2-positive, and triple negative (23). Histological classification, grading, and staging were performed according to internationally accepted guidelines (24,25).

Statistical analysis

The means and standard deviations (SDs) of continuous variables, as well as the medians and interquartile ranges, were analyzed using Student’s t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. Meanwhile, categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentages) and were compared using the χ2 (Chi-squared) test, Fisher’s exact test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Tertiles were categorized based on the distribution of TTHC and SR values and were used for further analyses. Tests of linear trend across tertiles of TTHC and SR were performed using the median value from each tertile. To predict the risk of ALNM, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using binary logistic regression analysis after adjusting for confounders. No adjustments were made to the crude model when calculating the crude OR (95% CI). Model 1 was adjusted for age. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for Ki-67 expression and grade based on model 1.

The predictors of ALNM were screened using univariate analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were drawn to evaluate the predictive performance of variables that were statistically significant for ALNM in previous analysis. The optimal cut-off values were analyzed using the Youden index. To facilitate clinical application and interpretation, the continuous variables (TTHC and SR) were converted into categorical variables according to the optimal cut-off based on the ROC curves. Collinearity among variables (TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression) was investigated using tolerance and variance inflation factors. Finally, an integrated prediction model was established by combining the imaging predictors (TTHC and SR) and the traditional biomarker (Ki-67) using binary logistic regression with the procedure “Enter”.

Differences in the predictive capability for ALNM were analyzed by comparing the areas under the curves (AUCs) using the Z test. Precision-recall curves were drawn, and the precision, recall, and F1-score were calculated to evaluate the model. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was conducted to assess the reliability, with P>0.05 indicating good agreement (adequate calibration). A calibration plot was constructed to assess the agreement between predicted and observed risks. Internal verification was performed using the 1,000-sample bootstrap method. Subgroup analyses were also performed to further investigate the predictive ability of the model based on different clinicopathological features (molecular subtype, pathological type, and grade). Interobserver agreement of TTHC and SR was calculated with the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC).

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 9.0; GraphPad Software, USA). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Histopathological analysis revealed that 56 patients (45.9%) had ALNM. Among the 122 patients, 39 (32.0%) were histologic grade I, 79 (64.8%) were grade II, and 4 (3.3%) were grade III. The associations between clinicopathological features and ALN status are summarized in Table 1. In univariate analysis, ALNM was significantly correlated with Ki-67 expression (P=0.002), clinical stage (P<0.001), TTHC (P<0.001), and SR (P<0.001), suggesting that these factors may have predictive value. The interobserver reliabilities of TTHC (ICC =0.83, P<0.001) and SR (ICC =0.82, P<0.001) were excellent. Representative preoperative DOT and SE images from one case with ALNM and one case without ALNM are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Total (n=122) | ALN-positive (n=56) | ALN-negative (n=66) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.66±10.16 | 50.38±8.88 | 50.91±11.20 | 0.774 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.50 (1.3–2.0) | 1.65 (1.3–2.0) | 1.50 (1.3–2.0) | 0.679 |

| Menstrual status | 0.209 | |||

| Pre- and perimenopause | 60 (49.2) | 31 (55.4) | 29 (43.9) | |

| Post-menopause | 62 (50.8) | 25 (44.6) | 37 (56.1) | |

| Immunohistochemical marker | ||||

| Ki-67 high expression | 51 (41.8) | 32 (57.1) | 19 (28.8) | 0.002* |

| ER-positive | 90 (73.8) | 45 (80.4) | 45 (68.2) | 0.128 |

| PR-positive | 101 (82.8) | 47 (83.9) | 54 (81.8) | 0.758 |

| HER2-positive | 37 (30.3) | 20 (35.7) | 17 (25.8) | 0.233 |

| Molecular subtype | 0.661 | |||

| Non-triple negative | 113 (92.6) | 53 (94.6) | 60 (90.9) | |

| Triple negative | 9 (7.4) | 3 (5.4) | 6 (9.1) | |

| Pathological type | 0.283 | |||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 115 (94.3) | 55 (98.2) | 60 (90.9) | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 4 (3.3) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (4.5) | |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 3 (2.5) | 0 | 3 (4.5) | |

| Clinical stage | <0.001* | |||

| I | 66 (54.1) | 0 | 66 (100.0) | |

| II | 41 (33.6) | 41 (73.2) | 0 | |

| III | 15 (12.3) | 15 (26.8) | 0 | |

| Grade | 0.108 | |||

| Grade I | 39 (32.0) | 15 (26.8) | 24 (36.4) | |

| Grade II | 79 (64.8) | 37 (66.1) | 42 (63.6) | |

| Grade III | 4 (3.3) | 4 (7.1) | 0 | |

| TTHC (μmol/L) | 193.78 (163.34–251.41) | 231.77±66.27 | 179.06 (148.4–213.35) | <0.001* |

| SR | 3.93 (3.21–5.38) | 4.55 (3.83–6.31) | 3.52 (2.9–4.56) | <0.001* |

For continuous variables, normal distributions are shown as mean ± standard deviation, and non-normal distributions as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are shown as numbers (percentages). Student’s t-test was used to calculate age; Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate tumor size, TTHC, and SR; Chi-squared test was used to calculate menstrual status, Ki-67 expression, ER expression, PR expression, HER2 expression, molecular subtype, and grade; Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate pathological type; Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to calculate clinical stage. *, P<0.05. ALN, axillary lymph node; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PR, progesterone receptor; SR, strain ratio; TTHC, tumor total hemoglobin concentration.

Association of the incidence of ALNM with TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression

The association between the incidence of ALNM and TTHC in patients with T1 BC is presented in Table 2. TTHC was positively associated with the incidence of ALNM before (P for trend <0.001) and after (P for trend <0.01) multivariate adjustments. The multivariate adjusted ORs (95% CIs) for ALNM incidence across the tertiles of TTHC were 1 (reference), 2.57 (0.97–6.85), and 5.60 (2.03–15.46). The OR (95% CI) for ALNM incidence per one SD increase in TTHC was 1.94 (1.28–2.96) after multivariate adjustments. The association between the incidence of ALNM and SR is shown in Table 2. A higher SR was associated with a higher incidence of ALNM before (P for trend <0.001) and after (P for trend <0.001) adjustment for confounders. The multivariate adjusted ORs (95% CIs) for ALNM incidence across the tertiles of SR were 1 (reference), 8.02 (2.64–24.40), and 10.95 (3.53–34.03). The multivariate adjusted OR (95% CI) for ALNM incidence per one SD increase in SR was 2.38 (1.46–3.89).

Table 2

| Variables | Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 | P for trend† | Per SD‡ increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTHC (μmol/L) | |||||

| Level, median (IQR) | 142.35 (120.40–164.18) |

194.11 (184.18–212.69) |

284.13 (251.41–323.92) |

– | – |

| No. of patients | 41 | 41 | 40 | – | – |

| No. of ALNM cases | 10 | 20 | 26 | – | – |

| Crude model, OR (95% CI) | Ref | 2.95 (1.15–7.56) | 5.76 (2.20–15.10) | <0.001 | 1.98 (1.32–2.97) |

| Adjusted model 1, OR (95% CI)§ | Ref | 2.95 (1.15–7.55) | 5.75 (2.19–15.09) | <0.001 | 1.98 (1.32–2.97) |

| Adjusted model 2, OR (95% CI)¶ | Ref | 2.57 (0.97–6.85) | 5.60 (2.03–15.46) | <0.01 | 1.94 (1.28–2.96) |

| SR | |||||

| Level, median (IQR) | 2.75 (2.15–3.29) | 3.95 (3.75–4.37) | 6.61 (5.38–7.85) | – | – |

| No. of patients | 42 | 40 | 40 | – | – |

| No. of ALNM cases | 8 | 23 | 25 | – | – |

| Crude model, OR (95% CI) | Ref | 5.75 (2.13–15.52) | 7.08 (2.60–19.28) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.37–3.31) |

| Adjusted model 1, OR (95% CI)§ | Ref | 5.77 (2.13–15.59) | 7.144 (2.62–19.49) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.37–3.32) |

| Adjusted model 2, OR (95% CI)¶ | Ref | 8.02 (2.64–24.40) | 10.95 (3.53–34.03) | <0.001 | 2.38 (1.46–3.89) |

Tertiles were categorized based on the distribution of TTHC and SR values. Tertile 1: 0th–33.3rd percentile; Tertile 2, 33.3rd–66.7th percentile; Tertile 3, 66.7th–100th percentile. †, multiple logistic regression analysis; ‡, SD of TTHC: 68.13 μmol/L, SD of SR: 2.09; §, adjusted for age; ¶, additionally adjusted for Ki-67 status and grade based on model 1. ALNM, axillary lymph node metastasis; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference; SD, standard deviation; SR, strain ratio; TTHC, tumor total hemoglobin concentration.

The association between the incidence of ALNM and Ki-67 expression is shown in Table 3. The results before (P for trend =0.002) and after (P for trend=0.004) adjustment for confounders indicated that high Ki-67 expression was associated with ALNM, even after adjusting for age and tumor grade. According to the fully adjusted model, Ki-67 expression had an OR (95% CI) of 3.40 (1.49–7.77) for predicting the risk of ALNM. Overall, these results indicated that TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression are independent risk factors of ALNM.

Table 3

| Variables | Ki-67 expression (n=122) | P† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<20%) | High (≥20%) | ||

| No. of patients | 71 | 51 | – |

| No. of ALNM cases | 24 | 32 | – |

| Crude model, OR (95% CI) | Ref | 3.30 (1.56–6.99) | 0.002 |

| Adjusted model 1, OR (95% CI)§ | Ref | 3.30 (1.56–6.99) | 0.002 |

| Adjusted model 2, OR (95% CI)¶ | Ref | 3.40 (1.49–7.77) | 0.004 |

†, multiple logistic regression analysis; §, adjusted for age; ¶, additionally adjusted for grade based on model 1. ALNM, axillary lymph node metastasis; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference.

Predictive performance of TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression for ALNM

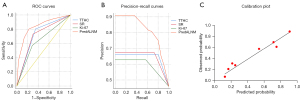

The predictive ability of TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression for ALNM was further analyzed using ROC curve analysis based on the pathological results. The AUCs of TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression for predictive ALNM (predALNM) were 0.707 (95% CI: 0.61–0.80), 0.718 (95% CI: 0.63–0.81) and 0.642 (95% CI: 0.56–0.73), respectively. The ROC curves showed that the optimal cut-off values for TTHC and SR were 185.75 µmol/L and 3.93, respectively. The Z-test indicated AUCs of these predictors were not significantly different (P>0.05), which supported that TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression had comparable predictive power.

Predictive performance of combination of TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression

The variance inflation factors for TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression were 1.155, 1.100, and 1.054, respectively, and the tolerance values were 0.866, 0.909, and 0.949, respectively. These results indicated that the three variables were independent of each other. A new model combining TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression was established using multivariate logistic analysis (Table S1). The new model for predALNM probability is generated according to the following mathematic expression: predALNM = −2.583 + 1.628 × TTHC + 1.786 × SR + 1.255 × Ki-67, where TTHC is ≥185.75 µmol/L, SR is ≥3.93, and Ki-67 expression is ≥20%, respectively.

The predictive performance of categorical variables TTHC and SR, Ki-67 expression, and predALNM were summarized in Table 4. The new model exhibited an AUC of 0.837 (95% CI: 0.76–0.91), demonstrating superior predictive performance compared to individual parameters alone (Z-test P<0.05) (Figure 4A).

Table 4

| Variables | Cut-offs | AUC (95% CI) | P | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | ||||||||

| TTHC (μmol/L) | ≥185.75 | 0.728 (0.65–0.81) | <0.001 | 80.4 | 65.2 | 72.1 | 66.2 | 79.6 |

| SR | ≥3.93 | 0.715 (0.63–0.80) | <0.001 | 73.2 | 69.7 | 71.3 | 67.2 | 75.4 |

| Traditional | ||||||||

| Ki-67 | ≥20% | 0.642 (0.56–0.73) | <0.01 | 57.1 | 71.2 | 64.8 | 62.7 | 66.2 |

| Combined | ||||||||

| PredALNM | ≥0.44 | 0.837 (0.76–0.91) | <0.001 | 80.4 | 77.3 | 78.7 | 75 | 82.3 |

ALNM, axillary lymph node metastasis; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; predALNM, predictive ALNM; PPV, positive predictive value; SR, strain ratio; TTHC, tumor total hemoglobin concentration.

Evaluation of the new model predALNM

Precision-recall curves of TTHC, SR, Ki-67 expression, and predALNM to further evaluate the prediction performance of the proposed model are shown in Figure 4B. PredALNM showed better performance than other individual factors. The precision, recall, and F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) were 0.750, 0.804, and 0.776, respectively. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test P value was 0.880, demonstrating good calibration. The calibration plot showed good and acceptable consistency between the actual observations and predictions (Figure 4C). Further verification using 1,000 resampling bootstrap analyses yielded an AUC of 0.837, which also demonstrated good accuracy of the prediction model.

Predictive performance of predALNM by subtype

Table S2 presents the results of the subgroup analyses. Positive predictive capabilities were demonstrated (AUC >0.75) within the subgroups of molecular subtype, pathological type, and grade. In particular, predALNM performed better in patients with invasive lobular carcinomas and triple-negative BC (AUC >0.90 for both).

Discussion

In the current study, higher TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression correlated with a higher risk of ALNM in T1 BC. The combination of imaging parameters (TTHC and SR) and pathological parameter (Ki-67 expression) demonstrated superior predictive performance than individual factor alone. As a simple and non-invasive method, the model can be used to rapidly assess the risk of ALNM and making individualized treatment decisions. To our best knowledge, this study provides the first systematic assessment of the relationship between TTHC, SR, and Ki-67 expression and ALNM in T1 BC.

The incidence of T1 BCs has increased with the implementation of BC screening programs (3). Notably, small tumors are associated with a certain risk of metastasize or recurrence (4). Some studies have indicated that small tumors with four or more metastatic lymph nodes are more aggressive and have higher BC-specific mortality than larger tumors (26,27). Early-stage BC patients have longer survival; therefore, they have higher requirements for postoperative quality of life. SLNB is the routine procedure for clinically lymph node-negative patients, but it has some limitations. Therefore, the development of an individualized diagnostic approach using non-invasive biomarkers to predict ALN status has become a research priority.

The mechanisms underlying ALNM in BC are not completely understood, but it may be the result of multiple factors. Current evidence indicates that tumor progression involves tumor cell proliferation and the extracellular microenvironment (28). Ki-67, a cellular marker for proliferation, is available from core needle biopsy of primary breast tumors, which is a standard procedure performed in patients with suspected BC. Consistent with previous research (29), the Ki-67 index was a predictor of ALNM in our study. In tumors, the homeostasis that governs extracellular matrix synthesis is disrupted, leading to abnormal vasculature formation and excessive fibrillar collagen accumulation (30). TTHC, a pivotal factor in the tumor microenvironment, reflects the functional and metabolic status of tumors. The current study found a close association between TTHC and ALNM in T1 BC, and this may be attributed to the abundant neovascularization in the tumor, which leads to increased tumor hemoglobin concentration.

The development of BC necessitates functional metabolic changes within the tissue, including microvessel formation. These functional alterations occur prior to the morphological changes detectable by conventional ultrasound (31). Concurrently, microstructures within BC, such as subcellular organelles, undergo significant alterations during tumor progression. An increase in both the number and density of subcellular organelles can enhance tissue scattering. Light scattering is particularly sensitive to angiogenesis and alterations in tissue microstructure (32), which may affect TTHC. As such, TTHC may have high sensitivity to metastasis. Niu et al. reported that ALNM is related to the microvessel density in primary BC (33), and consistent findings were observed in the current study. Tumor stiffness, another major factor in the tumor microenvironment, promotes tumor progression by β1 integrin signaling and TWIST1, high levels are also correlated with poor survival (34,35). Our results showed that SR ≥3.93 was an independent risk factor for ALNM, even after adjusting for clinicopathological confounding factors, consistent with a previous study (20). Additionally, another study has confirmed that the shear-wave elastography characteristics of breast tumors are significant predictors of axillary nodal burden (36).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate tumor cell features and multiple microenvironmental characteristics to predict ALNM in T1 BC. However, due to the inherent heterogeneity of BC, a single factor may be insufficient to accurately reflect prognosis. Accordingly, we developed a prediction model based on the combination of non-invasive imaging tools (DOT and SE) and Ki-67 expression to discriminate the risk of ALNM. The model showed adequate discrimination and yielded an AUC of 0.837. Notably, the high negative predictive value (82.3%) indicated that the model is beneficial for avoiding ineffective axillary surgery and reducing the adverse impact on quality of life. Additionally, both the calibration plot and internal validation confirmed repeatability and reliability. The predictive model for ALNM took into account tumor cell proliferation, tumor vascular distribution and relative tumor stiffness to provide a more effective and comprehensive approach. In addition, the model is applicable to non-sentinel lymph node metastases. Furthermore, all of these parameters are routinely available and therefore easy to use in the clinical setting. The model showed good predictive power (AUC >0.75) in different subgroups, emphasizing its stability and generalizability when applied to different patients. These results suggest that the model may help clinicians make more informed decisions. However, the underlying mechanisms require further investigation.

The current study has certain limitations. First, this was a single-center study comprising a relatively small sample size. The model should be validated in a multicenter study with a larger sample. Second, Ki-67 expression was determined from surgical specimens. This was because the data were collected earlier [2012], during which preoperative core needle biopsy was not yet widely available for T1 BC in our region. Although Ki-67 expression showed a high concordance rate (70.3–92.7%) between biopsy and pathological surgical specimens (37), this might also have resulted in some bias. We will further validate the performance of our model using Ki-67 expression obtained from preoperative biopsy. Third, the DOT technique has limitations. Lesions located <0.5 or >3.5 cm in depth cannot be measured owing to the limited penetration depth of near-infrared light. Optical image reconstruction requires the contrast of contralateral normal breast tissue; therefore, mirror-symmetric lesions of the contralateral breast were also excluded.

The combined approach presents several challenges, particularly in enhancing the accuracy and consistency of Ki-67 measurement and ultrasound assessment. Ki-67 measurement may be biased due to heterogeneity in specimen processing, measurement methods and statistical analyses (37). Therefore, the establishment of standardized international guidelines is essential for achieving satisfactory consistency. Furthermore, two essential measures should be implemented to ensure high quality and consistency of ultrasound results in clinical practice: first, the adoption of standardized operating procedures; and second, the utilization of the ‘quality indicator’ function available on the ultrasound device (38). Despite these challenges, Ki-67 remains a widely available and classic indicator commonly used in clinical practice. Concurrently, ultrasound imaging offers significant advantages, including broader accessibility, suitability for repeated examinations, higher spatial resolution, and real-time availability.

Artificial intelligence is advancing rapidly, deep learning combined with imaging and pathological parameters has achieved an AUC of 0.902 for ALNM prediction (10). However, this technique is still far from clinical application and warrants further exploration. Next-generation sequencing-based multigene assays are currently used to predict the risk of distant recurrence in ER-positive, HER2-negative BC (39). Additionally, ultrasound contrast-enhanced patterns of sentinel lymph nodes are utilized to assess lymph node metastatic burden (40). Radiomics methods are also used to identify patients at high risk of ALNM (41,42). The combination of genomics, histopathology, and radiomics shows promising predictive ability. In view of these findings, future research will focus on the integration of additional non-invasive techniques in large-scale multicenter studies, with the objective of enhancing the accuracy of ALNM prediction.

Conclusions

The study found that TTHC ≥185.75 µmol/L, SR ≥3.93 and Ki-67 expression ≥20% were strongly associated with ALNM in patients with T1 BC. The combined imaging–pathological parameter model might provide a convenient preoperative method for predicting ALN status, which can assist clinicians in individualizing management for patients with early-stage BC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank colleagues from the Departments of Breast surgery, Ultrasound, and Pathology for their help in data collection and technical support.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1664/rc

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1664/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the ethics committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (No. 2020PS748K) and informed consent was taken from all individual participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, Ahrendt GM, Wilke LG, Taback B, Leitch AM, Flippo-Morton TS, Kuerer HM, Bowling M, Hunt KKAlliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. Factors affecting sentinel lymph node identification rate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer patients enrolled in ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance). Ann Surg 2015;261:547-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Orr RK. The impact of prophylactic axillary node dissection on breast cancer survival--a Bayesian meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 1999;6:109-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Welch HG, Prorok PC, O'Malley AJ, Kramer BS. Breast-Cancer Tumor Size, Overdiagnosis, and Mammography Screening Effectiveness. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1438-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mook S, Knauer M, Bueno-de-Mesquita JM, Retel VP, Wesseling J, Linn SC, Van't Veer LJ, Rutgers EJ. Metastatic potential of T1 breast cancer can be predicted by the 70-gene MammaPrint signature. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1406-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, Meijnen P, van de Velde CJ, Mansel RE, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1303-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nori J, Vanzi E, Bazzocchi M, Bufalini FN, Distante V, Branconi F, Susini T. Role of axillary ultrasound examination in the selection of breast cancer patients for sentinel node biopsy. Am J Surg 2007;193:16-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeeravongpanich P, Chuangsuwanich T, Komoltri C, Ratanawichitrasin A. Histologic evaluation of sentinel and non-sentinel axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer by multilevel sectioning and predictors of non-sentinel metastasis. Gland Surg 2014;3:2-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu JL, Tseng HS, Yang LH, Wu HK, Kuo SJ, Chen ST, Chen DR. Prediction of axillary lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients based on pathologic information of the primary tumor. Med Sci Monit 2014;20:577-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu Y, Tan Y, Xie C, Hu Q, Ouyang J, Chen Y, et al. Development and Validation of a Preoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Radiomics-Based Signature to Predict Axillary Lymph Node Metastasis and Disease-Free Survival in Patients With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2028086. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng X, Yao Z, Huang Y, Yu Y, Wang Y, Liu Y, Mao R, Li F, Xiao Y, Wang Y, Hu Y, Yu J, Zhou J. Deep learning radiomics can predict axillary lymph node status in early-stage breast cancer. Nat Commun 2020;11:1236. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stachs A, Göde K, Hartmann S, Stengel B, Nierling U, Dieterich M, Reimer T, Gerber B. Accuracy of axillary ultrasound in preoperative nodal staging of breast cancer - size of metastases as limiting factor. Springerplus 2013;2:350. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang M, Tsimelzon A, Chang CH, Fan C, Wolff A, Perou CM, Hilsenbeck SG, Rosen JM. Intratumoral heterogeneity in a Trp53-null mouse model of human breast cancer. Cancer Discov 2015;5:520-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scarisbrick JJ, Prince HM, Vermeer MH, Quaglino P, Horwitz S, Porcu P, et al. Cutaneous Lymphoma International Consortium Study of Outcome in Advanced Stages of Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: Effect of Specific Prognostic Markers on Survival and Development of a Prognostic Model. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3766-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu X, Xue J, Peng S, Yang P, Yang Z, Yang L, Dong Y, Yuan L, Wang T, Bao G. Preoperative Nomogram for Predicting Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis Risk in Breast Cancer: A Potential Application on Omitting Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy. Front Oncol 2021;11:665240. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung MJ, Lee JH, Kim SH, Suh YJ, Choi HJ. Simple Prediction Model of Axillary Lymph Node Positivity After Analyzing Molecular and Clinical Factors in Early Breast Cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3689. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lam SW, Nota NM, Jager A, Bos MM, van den Bosch J, van der Velden AM, Portielje JE, Honkoop AH, van Tinteren H, Boven EATX Trial Team. Angiogenesis- and Hypoxia-Associated Proteins as Early Indicators of the Outcome in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer Given First-Line Bevacizumab-Based Therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:1611-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu Q, Xiao M, You S, Zhang J, Jiang Y, Lai X, Dai Q. Ultrasound-guided diffuse optical tomography (DOT) of invasive breast carcinoma: does tumour total haemoglobin concentration contribute to the prediction of axillary lymph node status? Eur J Radiol 2012;81:3185-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piersma B, Hayward MK, Weaver VM. Fibrosis and cancer: A strained relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2020;1873:188356. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Acerbi I, Cassereau L, Dean I, Shi Q, Au A, Park C, Chen YY, Liphardt J, Hwang ES, Weaver VM. Human breast cancer invasion and aggression correlates with ECM stiffening and immune cell infiltration. Integr Biol (Camb) 2015;7:1120-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JY, Shin JK, Lee SH. The Breast Tumor Strain Ratio Is a Predictive Parameter for Axillary Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients With Invasive Breast Cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;205:W630-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammond MEH, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, Fitzgibbons PL, Francis G, Goldstein NS, Hayes M, Hicks DG, Lester S, Love R, Mangu PB, McShane L, Miller K, Osborne CK, Paik S, Perlmutter J, Rhodes A. American Society of Clinical Oncology College of American Pathologists Guideline Recommendations for Immunohistochemical Testing of Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors in Breast Cancer (Unabridged Version). Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:e48-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sauter G, Lee J, Bartlett JM, Slamon DJ, Press MF. Guidelines for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing: biologic and methodologic considerations. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1323-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart M, Thürlimann B, Senn HJ. Panel members. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2206-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giuliano AE, Edge SB, Hortobagyi GN. Eighth Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2018;25:1783-5.

- Tan PH, Ellis I, Allison K, Brogi E, Fox SB, Lakhani S, Lazar AJ, Morris EA, Sahin A, Salgado R, Sapino A, Sasano H, Schnitt S, Sotiriou C, van Diest P, White VA, Lokuhetty D, Cree IAWHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the breast. Histopathology 2020;77:181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Provencher L, Diorio C, Hogue JC, Doyle C, Jacob S. Does breast cancer tumor size really matter that much? Breast 2012;21:682-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wo JY, Chen K, Neville BA, Lin NU, Punglia RS. Effect of very small tumor size on cancer-specific mortality in node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2619-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giussani M, Merlino G, Cappelletti V, Tagliabue E, Daidone MG. Tumor-extracellular matrix interactions: Identification of tools associated with breast cancer progression. Semin Cancer Biol 2015;35:3-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Li B, Liu Z, Shang H, Jing H, Shao H, Chen K, Liang X, Cheng W. Prediction model of axillary lymph node status using automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) and ki-67 status in early-stage breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2022;22:929. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeltz C, Primac I, Erusappan P, Alam J, Noel A, Gullberg D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in desmoplastic tumors: emerging role of integrins. Semin Cancer Biol 2020;62:166-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heijblom M, Klaase JM, van den Engh FM, van Leeuwen TG, Steenbergen W, Manohar S. Imaging tumor vascularization for detection and diagnosis of breast cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2011;10:607-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tabassum S, Tank A, Wang F, Karrobi K, Vergato C, Bigio IJ, Waxman DJ, Roblyer D. Optical scattering as an early marker of apoptosis during chemotherapy and antiangiogenic therapy in murine models of prostate and breast cancer. Neoplasia 2021;23:294-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niu S, Zhu Q, Jiang Y, Zhu J, Xiao M, You S, Zhou W, Xiao Y. Correlations Among Ultrasound-Guided Diffuse Optical Tomography, Microvessel Density, and Breast Cancer Prognosis. J Ultrasound Med 2018;37:833-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, Weaver VM. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 2009;139:891-906. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei SC, Fattet L, Tsai JH, Guo Y, Pai VH, Majeski HE, Chen AC, Sah RL, Taylor SS, Engler AJ, Yang J. Matrix stiffness drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumour metastasis through a TWIST1-G3BP2 mechanotransduction pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2015;17:678-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Yang J, Tang YL, Chen YY, Luo J, Cui XW, Dietrich CF, Yi AJ. The value of microvascular Doppler ultrasound technique, qualitative or quantitative shear-wave elastography of breast lesions for predicting axillary nodal burden in patients with breast cancer. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2024;14:408-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalvala J, Parks RM, Green AR, Cheung KL. Concordance between core needle biopsy and surgical excision specimens for Ki-67 in breast cancer - a systematic review of the literature. Histopathology 2022;80:468-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barr RG. Breast Elastography: How to Perform and Integrate Into a "Best-Practice" Patient Treatment Algorithm. J Ultrasound Med 2020;39:7-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HB, Lee SB, Kim M, Kwon S, Jo J, Kim J, Lee HJ, Ryu HS, Lee JW, Kim C, Jeong J, Kim H, Noh DY, Park IA, Ahn SH, Kim S, Yoon S, Kim A, Han W. Development and Validation of a Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Multigene Assay to Predict the Prognosis of Estrogen Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:6513-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu Y, Jia Y, Pang W, Duan Y, Chen K, Nie F. Ultrasound contrast-enhanced patterns of sentinel lymph nodes: predictive value for nodal status and metastatic burden in early breast cancer. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023;13:160-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei W, Ma Q, Feng H, Wei T, Jiang F, Fan L, Zhang W, Xu J, Zhang X. Deep learning radiomics for prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis in patients with clinical stage T1-2 breast cancer. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023;13:4995-5011. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Nie L, Zhu Q, Zuo Z, Liu G, Sun Q, Zhai J, Li J. Artificial intelligence assisted ultrasound for the non-invasive prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2024;24:910. [Crossref] [PubMed]