Fat-separated T1 mapping for liver function analysis on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging: 2D two-point Dixon Look-Locker inversion recovery sequence for differentiation of Child-Pugh class B/C from Child-Pugh class A/chronic liver disease

Introduction

Evaluation of liver function in chronic liver disease (CLD) or liver cirrhosis (LC) is crucial for therapeutic decision-making and the prediction of prognosis (1).

Several methods are available for assessing hepatic functional capacity. Serologic tests, including liver enzymes, bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, and fibrogenesis-related biomarkers, represent simple yet conventional non-invasive methods. Hepatic parenchymal enhancement on gadoxetic acid (GA)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during the hepatobiliary phase (HBP) can accurately reflect hepatic function and has been studied as an alternative to indocyanine green kinetics and hepatobiliary scintigraphy (2-5). Visual assessment of HBP enhancement has been studied using categorical grading (6,7) whereas quantitative measurement of HBP enhancement can be confounded by several imaging parameters and technical factors (6,8).

Hepatic T1 relaxation time measured by magnetic resonance (MR) relaxometry is a tissue-specific parameter that correlates with the hepatic concentration of GA or hepatic fibrosis, and increases with the progression of cirrhosis, showing associations with other functional parameters (8-11). T1 mapping serves as a tool that can be implemented without additional hardware, and is not affected by an individual’s body habitus, including factors like obesity or ascites. However, T1 values can be influenced by histological components other than fibrosis, such as fat, iron, edema, and inflammation (12). Previous studies have shown that the T1 values decrease with iron overload and increase in the presence of edema and inflammation (12-18). In addition, T1 varies with echo time in the presence of liver fat (19). Alteration in fat content in the liver or coexisting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is relatively common in patients with CLD or LC; therefore, it is important to eliminate the influence of fat tissue for a precise quantitative assessment of hepatic function using T1 mapping.

The purpose of this study was to obtain fat-separated T1 values using a Look-Locker inversion recovery (LLIR) with Dixon sequence on GA-enhanced MRI, and to investigate the role of Dixon watermap T1 for the assessment of hepatic function. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-805/rc).

Methods

Patients

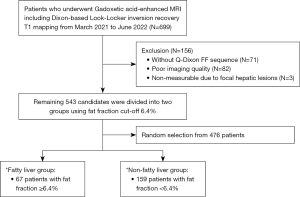

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyung Hee University Hospital (No. 2023-12-032). Individual consent for this retrospective study was waived. Between March 2021 and June 2022, 699 patients who underwent GA-enhanced liver MRI, including the Dixon-coupled LLIR sequence (prototype, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany), were enrolled in Kyung Hee University Hospital retrospectively. Among them, 156 patients were excluded for the following reasons: (I) absence of the Q-Dixon proton density fat fraction (PDFF) map sequence (n=71); (II) inability to define the hepatic contour due to poor image quality or incomplete coverage of the whole liver (n=82); and (III) non-measurable due to focal hepatic lesions (n=3). The remaining 543 patients were divided into two groups using a fat fraction (FF) cutoff 6.4% [according to previously determined cut-off for defining fatty liver (FL) (20)], and 67 patients were included in the FL group (FF ≥6.4%). To match the numbers between the fatty and non-fatty groups, random selection was performed among the 476 patients; 159 patients were included as the non-fatty liver (NFL) group (male-to-female ratio, 168:58, Figure 1). For these patients, the etiology of the underlying liver disease, serum albumin, total bilirubin (TB), prothrombin time, and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase levels were checked by reviewing electronic medical records. The Child-Pugh (CP) class was determined using a combination of clinical and imaging findings.

MR image acquisition

All imaging was performed using a 3T MRI (MAGNETOM Vida; Siemens Healthineers) with a 30-channel phased-array body coil. With a 6-point multi-echo Dixon volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination sequence (q-Dixon), the T2* corrected PDFF map and additional R2* map were automatically generated on the scanner. The scan parameters were as follows: echo time (TE), 0.9/1.77/2.64/3.51/4.38/5.25 ms; repetition time (TR), 6.3 ms; flip angle 3°; field-of-view (FOV), 440×303 mm2; matrix 128×88; slice thickness 3 mm; number of slices 60; acceleration factor 2×2; scan time 10 s.

T1 maps were obtained using LLIR (work in progress) sequences in two types; one is a composite T1 map without coupling with Dixon, and the other is a Dixon T1 map that allows obtaining a T1 map with fat and water separated. After the non-selective inversion pulse, a single-shot 2-dimensional spoiled fast low-angle shot readout for Look-Locker sampling were used to continuously sample the T1 magnetization recovery curve. Multiple inversion time (TI) images are then processed using a pixel-wise three parameter nonlinear least-squares fitting to estimate the T1 map (21).

Both composite and Dixon T1 maps were acquired twice, before and 20 minutes after GA administration, and one slice covering the largest area of liver parenchyma was acquired for scanning during expiratory breath-holding. The scan parameters for the Dixon T1 maps were as follows: TR/TE1/TE2 3.5/1.23/2.46 ms; flip angle, 8 degrees; FOV 350 mm; acquisition matrix, 128×64; acceleration factor, 2; slice thickness, 6 mm; receiver bandwidth 1,500 Hz/pixel; scan time 15 s. Composite T1 maps were acquired with single echo (TR/TE 3 ms/1.3 ms) and the other parameters were identical. For both composite and Dixon T1 map, a total of 30 images with different effective TI were acquired at 155.32 ms intervals, and the acquired TI range was 86.16–4,590.44 ms after a non-selective inversion pulse during single breath-hold. In the Dixon T1 map (hereafter, watermap T1), images were acquired at two echo times selected as out-phase and in-phase after the inversion recovery pulse. From these two corresponding inverted images, a fat-only and a water-only T1 map were calculated by the two-point Dixon algorithm (22,23).

Image analysis

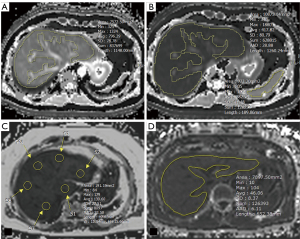

For measurement of T1 values, two independent reviewers (Y.R.H., 5 years of experience in MR; M.S., 1-year of experience in MR) drew free-hand regions of interest (ROIs) on each slice of conventional pre-enhanced and post-enhanced T1 and watermap preT1 and postT1 maps (mean area, 7,743.37 mm2) blinded to clinical data and CP classes. ROIs were placed on the preT1 maps, and then copied and pasted onto the watermap preT1, postT1, and watermap postT1 maps. During the procedure, ROIs were adjusted according to the outer edge of the liver if the contour or level of the liver parenchyma did not match the original images. Focal lesions and major branches of hepatic vessels were carefully avoided. Two reviewers repeated the T1 measurement with a 2-week interval to assess reproducibility. The mean values of the ROIs were considered the representative T1 relaxation times of the liver and spleen (Figure 2). Two additional parameters were obtained; deltaT1 liver was defined as (preT1 − postT1)/preT1 to assess the GA uptake by functioning hepatocytes, and adjusted T1 was defined as [(postT1 liver − postT1 spleen)/postT1 spleen] to assess the degree of HBP enhancement without the effect of extracellular enhancement (8,24).

One of the two reviewers (Y.R.H.) drew two circular ROIs in each segment of liver on the Q-Dixon PDFF map, and the mean liver FF was calculated by averaging the FFs in a total of 18 ROIs in nine hepatic segments, according to the Couinaud classification (25). The same reviewer drew a freehand ROI with the same method of T1 measurement at the level where the liver appeared widest on the R2* map, to assess liver iron content.

The two reviewers visually assessed the liver morphology and liver parenchymal enhancement on HBP by consensus. Liver morphology was classified as normal, CLD, or LC according to previously defined criteria (26,27). HBP enhancement grade was categorized into three; Grade 1 marked hypointense vessels compared to liver parenchyma, Grade 2 mild hypointense vessels, and Grade 3 isointense vessels (6,7).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as percentages, and numerical data were presented as means with standard deviations or medians with range, depending on whether or not they were Gaussian distributions. Comparison of clinical data and T1 parameters between the fatty and non-fatty groups was performed using the independent t-test. We used the t-test to compare two groups because the study population was greater than 30 in each group, although there were deviations from the normal distribution of the data. Reproducibility of T1 measurement was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) >0.81, almost perfect, 0.61–0.81, substantial, 0.41–0.60, moderate, 0.21–0.40, fair; and Bland-Altman plots. The correlation between T1 parameters and liver FF was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficient (r), and multivariable linear regression analysis was performed to determine predictive factors for T1 parameters; the determination coefficient (R2) and adjusted R2 were generated. All the results are presented with 95% confidence intervals and standard errors (SEs). Data are assumed to be missing at random, and all analysis was restricted to cases with complete data on all variables. We didn’t use multiple imputation or sensitivity analysis to deal with missing data. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to assess the diagnostic performance of T1 values in differentiating CP class B/C from CP class A/CLD. All statistical analyses were performed using Medcalc ver.20.111 (Medcalc software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium) and P<0.05 was defined as clinically significant.

Results

Clinical data and T1 parameters of included patients

Table 1 shows the descriptive data of the included patients. Mean age was 63.96±10.74, and most of the patients had viral B or viral C hepatitis (121/226, 53.5%). Mean preT1, postT1, and deltaT1 were 875.58±131.58 ms, 290.36±109.81 ms, and 0.668±0.113, respectively, and mean watermap preT1, watermap postT1, and watermap deltaT1 were 774.39±162.11 ms, 283.15±114.47 ms, and 0.625±0.149, respectively. Adjusted T1 and watermap adjusted T1 did not show any significant difference from postT1 or fat correction effect.

Table 1

| Patients’ data | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.96±10.74 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 168 (74.3) |

| Female | 58 (25.7) |

| Underlying disease | |

| Viral B hepatitis | 113 (50.0) |

| Viral C hepatitis | 8 (3.5) |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 37 (16.4) |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 5 (2.2) |

| NonB nonC hepatitis | 8 (3.5) |

| Unknown | 55 (24.3) |

| PreT1 (ms) | 875.58±131.58 |

| Watermap preT1 (ms) | 774.39±162.11 |

| PostT1 (ms) | 290.36±109.81 |

| Watermap postT1 (ms) | 283.15±114.47 |

| DeltaT1 | 0.668±0.113 |

| Watermap deltaT1 | 0.625±0.149 |

| Adjusted T1 | 0.676±0.128 |

| Watermap adjusted T1 | 0.653±0.164 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | 44.9 [12.7–392.3] |

| Fat fraction (%) | 3.22 [0.81–34.53] |

| Spleen (cm) | 10.15±2.00 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.2 [2.2–5.0] |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 27 [6–368] |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 35 [12–426] |

| Prothrombin time international normalized ratio | 1.02 [0.85–1.91] |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.86 [0.21–35.62] |

| Hepatobiliary phase enhancement grade | |

| Grade 1: marked hypointense vessel | 161 (72.5) |

| Grade 2: mild hypointense vessel | 38 (17.1) |

| Grade 3: isointense vessel | 23 (10.4) |

| Liver morphology | |

| Normal | 61 (26.9) |

| Chronic liver disease | 25 (11.1) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 140 (61.9) |

| CP class | |

| Normal/chronic liver disease | 86 (38.1) |

| CP class A | 131 (58.0) |

| CP class B | 8 (3.5) |

| CP class C | 1 (0.4) |

Values are presented as mean ± SD, n (%) or median [range]. IU, international unit; CP, Child-Pugh; SD, standard deviation.

Median liver FF was 3.22% (0.81–34.53%). Most of the patients had liver cirrhosis (61.9%, 140/226), 11.1% had CLD (25/226), and 26.9% had normal liver (61/226). Most of the patients with liver cirrhosis had CP class A (131/140), followed by CP class B (8/140) and CP class C (1/140). The majority of the patients showed normal HBP enhancement (72.5%, 161/226).

Comparison of T1 parameters between the FL and NFL groups

Mean preT1 was significantly longer in the FL group than that in the NFL group (926.38±133.48 vs. 855.26±125.58 ms, P<0.0001); however, watermap preT1 in the FL group decreased and showed no significant difference with that in the NFL group (736.66±177.11 vs. 789.33±153.83 ms, P=0.272) after fat separation. Likewise, deltaT1 in the FL group was significantly higher than that in the NFL group (0.70±0.01 vs. 0.66±0.12, P=0.033) while watermap deltaT1 in the FL group and the NFL group showed no significant difference (0.62±0.16 vs. 0.63±0.14, P=0.779). PostT1 showed no differences between the FL and NFL groups, as did watermap postT1 (P>0.05, Table 2).

Table 2

| Patients’ data | Fatty liver group (n=67) | Non-fatty liver group (n=159) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PreT1 (ms) | 926.38 (133.48) | 855.26 (125.58) | <0.0001 |

| Watermap preT1 (ms) | 736.66 (177.11) | 789.33 (153.83) | 0.272 |

| PostT1 (ms) | 278.06 (96.12) | 295.23 (114.71) | 0.303 |

| Watermap postT1 (ms) | 265.2 1(71.11) | 290.14 (126.94) | 0.071 |

| DeltaT1 | 0.70 (0.01) | 0.66 (0.12) | 0.033 |

| Watermap deltaT1 | 0.62 (0.16) | 0.63 (0.14) | 0.779 |

| Adjusted T1 | 0.70 (0.10) | 0.67 (0.14) | 0.110 |

| Watermap adjusted T1 | 0.66 (0.15) | 0.65 (0.169) | 0.701 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | 62.8 (4.731) | 53.0 (3.988) | 0.116 |

| Fat fraction (%) | 10.81 (1.57) | 2.76 (1.33) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.29 (0.39) | 4.06 (0.53) | 0.001 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 38.6 (44.86) | 33.8 (36.54) | 0.404 |

| AST (IU/L) | 47.54 (51.38) | 43.24 (39.12) | 0.494 |

| PT INR | 1.03 (0.14) | 1.04 (0.12) | 0.490 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.99 (0.60) | 1.43 (3.21) | 0.280 |

Values are presented as mean (SD). ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; IU, international unit; PT INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; SD, standard deviation.

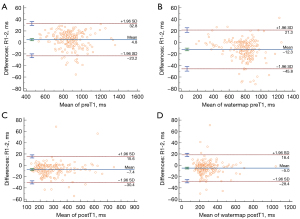

Repeatability and reproducibility of the measurement of T1 values on T1 mapping

Interobserver and intraobserver agreements were assessed for T1 parameters and are presented in Table 3 and Figure 3. All T1 parameters, including preT1, watermap preT1, postT1, and watermap postT1 showed almost perfect agreement (interobserver 0.980–0.995; Reader 1 0.998–0.999; Reader 2 0.929–0.996). Bland-Altman plot shows mean bias of preT1 4.8 ms [95% limit of agreement (LOA): −23.2 to 32.8], watermap preT1 −12.3 ms (95% LOA: −45.8 to 21.3), postT1 −7.4 ms (95% LOA: −30.4 to 15.6), and watermap postT1 −5 ms (95% LOA: −28.4 to 18.4) between the two reviewers.

Table 3

| Reproducibility and repeatability | Composite preT1 map | Watermap preT1 | Composite postT1 map | Watermap postT1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interobserver reproducibility | 0.986 (0.964–0.989) | 0.987 (0.984–0.989) | 0.980 (0.975–0.984) | 0.995 (0.994–0.996) |

| Repeatability | ||||

| Reader 1 | 0.998 (0.998–0.999) | 0.999 (0.999–0.999) | 0.999 (0.998–0.999) | 0.999 (0.999–1.000) |

| Reader 2 | 0.979 (0.972–0.984) | 0.996 (0.995–0.997) | 0.929 (0.907–0.946) | 0.986 (0.982–0.989) |

Values are presented as ICC (95% CI). ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

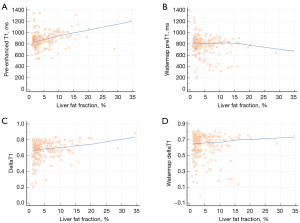

Correlation between T1 parameters and fat fraction

Changes in the correlation between T1 parameters and FF after fat correction are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4. PreT1 and deltaT1 showed significant positive correlations with FF (P<0.0001, 0.0002) while watermap preT1 and watermap deltaT1 showed no correlation with FF (P=0.068, 0.414). PostT1 showed no significant correlation with FF, with or without fat correction.

Table 4

| T1 value | Fat fraction (%), r (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| PreT1 | 0.277 (0.158 to 0.404) | <0.0001 |

| Watermap preT1 | −0.125 (−0.288 to 0.027) | 0.068 |

| PostT1 | 0.159 (−0.286 to −0.026) | 0.018 |

| Watermap postT1 | 0.153 (−0.280 to −0.019) | 0.024 |

| DeltaT1 | 0.245 (0.123 to 0.374) | 0.0002 |

| Watermap deltaT1 | 0.055 (−0.112 to 0.157) | 0.414 |

| Adjusted T1 | 0.134 (−0.006 to 0.268) | 0.060 |

| Watermap adjusted T1 | 0.06 (−0.075 to 0.203) | 0.362 |

r, Pearson correlation coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

Multivariate linear regression analyses for variables affecting liver T1

Tables 5-10 present the predictive factors for T1 values and the changes in related factors after fat correction. FF, R2* values, HBP enhancement grade, and TB were significant factors in predicting preT1, whereas R2* values and HBP enhancement grade were the only remaining factors in predicting watermap preT1. Similarly, FF, HBP enhancement grade, TB, and albumin were significant factors in predicting deltaT1, while FF was eliminated after fat correction. R2* values, HBP enhancement grade, and albumin were the significant factors in predicting both adjusted T1 and watermap adjusted T1, however FF was not the significant factors for both.

Table 5

| Variables | Regression coefficient (standard error) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Fat fraction (%) | 10.710 (1.367) | <0.0001 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | −1.962 (0.148) | <0.0001 |

| HBP enhancement, grade (per grade) | 59.254 (12.937) | <0.0001 |

| AST (IU/L) | −0.113 (0.257) | 0.662 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 0.554 (0.283) | 0.052 |

| PT INR | 40.945 (51.918) | 0.431 |

| TB (mg/dL) | −9.418 (2.370) | 0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | −37.985 (15.431) | 0.015 |

| CP class (per score class) | 11.446 (11.365) | 0.315 |

The determination coefficient was R2=0.581, and the adjusted determination coefficient was R2a=0.565. HBP, hepatobiliary phase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IU, international unit; PT INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; CP, Child-Pugh.

Table 6

| Variables | Regression coefficient (standard error) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Fat fraction (%) | −2.376 (2.289) | 0.301 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | −1.759 (0.276) | <0.0001 |

| HBP enhancement, grade (per grade) | 60.139 (21.594) | 0.006 |

| AST (IU/L) | −0.335 (0.429) | 0.437 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 0.079 (0.473) | 0.867 |

| PT INR | 116.265 (86.798) | 0.182 |

| TB (mg/dL) | −3.008 (3.959) | 0.448 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | −0.333 (25.772) | 0.989 |

| CP class (per score class) | 2.968 (18.962) | 0.876 |

The determination coefficient was R2=0.219, and the adjusted determination coefficient was R2a=0.184. HBP, hepatobiliary phase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IU, international unit; PT INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; CP, Child-Pugh.

Table 7

| Variables | Regression coefficient (standard error) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Fat fraction (%) | 0.005 (0.001) | <0.0001 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | 0.00004 (0.0001) | 0.725 |

| HBP enhancement, grade (per grade) | −0.073 (0.011) | <0.0001 |

| AST (IU/L) | −0.0004 (0.0002) | 0.069 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 0.0001 (0.0002) | 0.498 |

| PT INR | −0.077 (0.043) | 0.077 |

| TB (mg/dL) | −0.012 (0.002) | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.031 (0.013) | 0.018 |

| CP class (per score class) | 0.010 (0.009) | 0.286 |

The determination coefficient was R2=0.627, and the adjusted determination coefficient was adjusted R2a=0.609. HBP, hepatobiliary phase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IU, international unit; PT INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; CP, Child-Pugh.

Table 8

| Variables | Regression coefficient (standard error) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Fat fraction (%) | −0.0001 (0.002) | 0.918 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | −0.00004 (0.0003) | 0.875 |

| HBP enhancement, grade (per grade) | −0.061 (0.018) | 0.001 |

| AST (IU/L) | −0.008 (0.0004) | 0.028 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 0.0003 (0.0003) | 0.445 |

| PT INR | −0.042 (0.073) | 0.570 |

| TB (mg/dL) | −0.009 (0.003) | 0.006 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.060 (0.022) | 0.006 |

| CP class (per score class) | 0.003 (0.016) | 0.869 |

The determination coefficient was R2=0.373, and the adjusted determination coefficient was R2a=0.344. HBP, hepatobiliary phase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IU, international unit; PT INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; CP, Child-Pugh.

Table 9

| Variables | Regression coefficient (standard error) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Fat fraction (%) | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.164 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | 0.0005 (0.0002) | 0.009 |

| HBP enhancement, grade (per grade) | −0.104 (0.014) | <0.001 |

| AST (IU/L) | 0.00002 (0.0003) | 0.929 |

| ALT (IU/L) | −0.0002 (0.0003) | 0.438 |

| PT INR | −0.098 (0.055) | 0.071 |

| TB (mg/dL) | −0.006 (0.002) | 0.023 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.038 (0.017) | 0.023 |

| CP class (per score class) | −0.009 (0.012) | 0.471 |

The determination coefficient was R2=0.552, and the adjusted determination coefficient was R2a=0.530. HBP, hepatobiliary phase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IU, international unit; PT INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; CP, Child-Pugh.

Table 10

| Variables | Regression coefficient (standard error) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Fat fraction (%) | −0.0001 (0.002) | 0.954 |

| R2* (s−1 Hz) | 0.0005 (0.0002) | 0.035 |

| HBP enhancement, grade (per grade) | −0.099 (0.019) | <0.0001 |

| AST (IU/L) | −0.0002 (0.0004) | 0.646 |

| ALT (IU/L) | −0.0004 (0.0004) | 0.297 |

| PT INR | −0.114 (0.077) | 0.140 |

| TB (mg/dL) | −0.002 (0.003) | 0.490 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.092 (0.023) | 0.0001 |

| CP class (per score class) | 0.001 (0.017) | 0.934 |

The determination coefficient was R2=0.476, and the adjusted determination coefficient was R2a=0.449. HBP, hepatobiliary phase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IU, international unit; PT INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; TB, total bilirubin; CP, Child-Pugh.

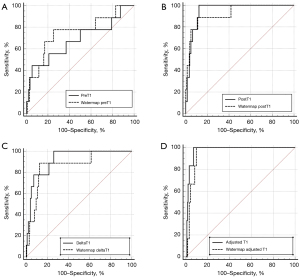

ROC curve analysis of liver T1 for diagnosing hepatic decompensation

Figure 5 shows the diagnostic performance of liver T1 in differentiating patients with CP classes of B/C from others. The area under the curve (AUC) of fat-separated watermap preT1 was slightly higher (0.748, SE 0.098) than that of preT1 (0.681, SE 0.114), although there was no statistically significant difference (P=0.098). The AUC of postT1 (0.951, SE 0.018) and deltaT1 (0.921, SE 0.033) were similar but slightly higher than watermap postT1 (0.925, SE 0.045) and watermap deltaT1 (0.866, SE 0.063), without statistically significant differences (P>0.05). Both adjusted T1 (0.973, SE 0.013) and watermap adjusted T1 (0.950, SE 0.018) showed the highest AUCs along with postT1 (0.951, SE 0.018), followed by watermap postT1 (0.925, SE 0.045) and deltaT1 (0.921, SE 0.033).

Discussion

Liver function assessment using MR images allows a multi-dimensional approach including hepatic morphologic changes, qualitative or semi-quantitative parenchymal signal intensity (SI) assessment in HBP, and T1 relaxometry. SI-based indices on GA-enhanced MR are known to be useful parameters for estimating liver function. It can be performed with visual assessment by grading or with more objective and quantitative assessment by ROI measurement of SI and calculation of liver-spleen contrast ratio. Several studies investigated and compared the correlation of GA-enhanced MR SI-based indices and T1 relaxometry parameters with liver function, and reported the superiority of T1 map (24,28-30). T1 mapping on GA-enhanced MR correlates with quantitative assessment of liver HBP enhancement. In addition, T1 relaxometry provides a non-invasive and quantitative assessment of liver function that can be obtained within a single breath hold and independent of GA enhancement.

In our study, preT1 and deltaT1 on Dixon watermap images demonstrated significant correlation with TB, albumin, and qualitative HBP enhancement grade with eliminated confounding effect of fat. Higashi et al. also reported the reduced effect of fat on T1 value using Dixon water images compared with in-phase and out-of-phase based T1 values (19). Our study further explored fat-separated T1 values in both pre- and post-GA-enhanced MR using Dixon-coupled LLIR, and found that the fat correction effect was more pronounced in watermap preT1 than postT1.

Previous studies have reported that fat influences liver T1 values; therefore, fat must be corrected when using T1 mapping (18,19,31,32). Composite preT1 without fat separation was generated using a single exponential fit, producing an apparent T1 from the different T1-values of the fat and water signals (19,33). Depending on the echo time, the composite T1 can be longer or shorter than the watermap T1 as the fat signal changes from being in-phase to out-of-phase to the water signal, according to the echo time changes (34). Ahn et al. demonstrated that the liver T1 value increases as the steatosis grade increases and correlates with the fat fraction (31), which is consistent with our study. The elevated T1 value in steatotic liver decreases with fat correction because hepatic steatosis is a common response to injury, and is therefore usually associated with edema and inflammation caused by various conditions such as alcohol, toxin, infection, or metabolic steatotic liver disease (18,35). As hepatic steatosis may coexist in patients with CLD or LC, T1 relaxometry using Dixon-coupled LLIR allows the isolated T1 measurement of the water fraction, and may be a useful quantitative biomarker for non-invasive assessment of liver function.

Many previous studies have reported that hepatic T1 mapping using MR relaxometry is associated with liver fibrosis (13), CP classes (10,29,36), esophageal varices (8), and hepatic insufficiency and decompensation (34,37). In our study, T1 parameters using Dixon-coupled LLIR can discriminate higher CP class group (B/C) from normal and lower CP class group (A) with favorable diagnostic performance (AUC ranging 0.68–0.97). According to previous studies, pre- and postT1 were significantly prolonged with increasing CP class (9,38), as shown in our study. In addition, adjusted T1 and postT1 showed the highest diagnostic performance for advanced cirrhosis (CP class B/C), followed by deltaT1 and preT1, which is consistent with previous studies that reported the superior correlation effect of postT1 compared with preT1 (29,37,39). Both pre- and postT1 are associated with liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, however, the change in preT1 is rather nonspecific and may be influenced by other factors (11,40,41). On the other hand, postT1 is associated with preT1 and reflects decreased hepatic uptake of contrast media due to decreased organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1, which is related to hepatocyte function. We studied T1 relaxometry in both pre- and post-enhanced scans and found that the fat separation effect was dominant on preT1 and deltaT1 while post-enhanced T1 parameters (postT1 and adjusted T1) showed little difference between composite and watermap T1 and were less affected by fat fraction. GA enhancement shortens the T1 relaxation time in the liver, which is similar to the T1 of subcutaneous and liver fat (371 ms at 3T) (33). The reduced difference between T1 and watermap T1 after contrast injection may be due to the similar range of fat T1 and watermap T1 after contrast injection. This may explain the less pronounced fat-separation effect of postT1, as postT1 approaches a similar value to fat T1 itself.

PostT1 obtained at 20 minutes after GA-enhancement reflect HBP enhancement, and further enables quantitative measurement of liver parenchymal enhancement. SI measurement on HBP is simple and direct method to evaluate liver function, however it can be variable depending on several technical factors and scanning parameters (6,29). PostT1 can be a good complementary and quantitative tool for liver function assessment in one additional single breath-hold scan.

Recent studies have reported the effectiveness of fat separation for accurate assessment of liver T1 (19,32,42). Our study investigated the clinical application of fat-separated T1 using 2D two-point Dixon LLIR, and suggested that watermap T1 mapping can more accurately assess liver function and fibrosis with less influence of hepatic steatosis. Fellner et al. studied fat-separated T1 map using variable flip angle (VFA) sequence with Dixon water-fat separation and reported that the difference between in-phase T1 and water-only T1 correlated with fat fraction (32). We used Dixon watermap T1 LLIR, which is a prototype of fat-separated T1, and it was investigated for both pre- and post-GA-enhanced MR in this work. LLIR or modified LLIR is one of the actively used clinical technique for T1 mapping, and has several advantages in terms of speed, accuracy, and good reproducibility (42,43). It is timely efficient that is obtainable in a single breath hold, constant for image acquisition and analysis, less prone to B1 field inhomogeneity than VFA method, and less affected by field strength than SI measurement (8,19,37). Our Dixon watermap T1 LLIR can be a robust imaging biomarker for liver function assessment with elimination of the confounding effect of fat in addition to the advantages of LLIR compared to other T1 mapping such as VFA technique.

The intra- and inter-observer agreement for the measurement of T1 parameters was almost perfect, and mean bias of preT1 and water preT1 was within 13 ms, with a range of 95% LOA within 70 ms. Similar studies have reported good reproducibility of liver T1 measurements (31,44); however, there is a lack of data regarding reproducibility across vendors, field strengths, and temporal assessments. Future studies should investigate the thresholds for distinguishing true changes beyond the clinically acceptable range of reproducibility in T1 measurement to develop a more standardized imaging biomarker for liver function assessment.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study in which we selected the FL group with a predefined FF threshold, and there were several missing and incomplete clinical data. However, the reviewer who drew ROIs for liver fat measurement was blinded for the clinical information and the study results, and independent another author performed data comparison between FL and NFL groups. Second, the study cohort was heterogeneous and consisted of patients with normal livers, CLD, and LC. We consecutively collected MR exam with Dixon LLIR sequence for T1 mapping regardless of etiology and indication for liver MR. Third, liver function was assessed using laboratory data only. We did not perform MR elastography or biopsy to evaluate liver fibrosis. However, we aimed to develop an easily-obtainable and simple method to evaluate liver function without additional software implementation or invasive procedure. Fourth, only a small proportion of patients with CP class C were included, so the comparability between CP classes may be limited. Therefore, we combined CP class B and C as one group, and CP class A and CLD as another group to facilitate the comparability between the two groups. Fifth, ROIs from the composite preT1 map were copied and pasted onto the watermap T1 and postT1, so there could be errors in the fitting of the ROIs due to motion and different breath holding levels. However, the operator additionally adjusted the ROIs according to the outer edge of the liver in case of mismatch errors. Sixth, although R2* was a significant factor for all T1 parameters, we did not perform iron correction. Iron overload reduces T1 value and excess iron levels in the presence of fibrosis can lead to pseudo-normal T1. However, since our study population mostly showed iron level within normal limit (R2* 136/s > at 3T MR), we did not consider iron correction for T1 evaluation as shown in a previous study (45). Seventh, we did not evaluate clinical outcomes, such as the development of hepatic insufficiency or decompensation. Further longitudinal study to investigate whether T1 parameters can predict clinical outcome after follow-up would be recommended.

Conclusions

In conclusion, fat-separated T1 mapping using Dixon-coupled LLIR effectively eliminated the confounding effect of fat in preT1 and deltaT1. Dixon watermap T1 with or without GA enhancement correlated significantly with representative serologic and imaging biomarkers of liver function, and adjusted T1 and postT1 showed superior diagnostic performance in differentiating advanced CP classes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the nonfinancial technical support from Siemens Healthineers.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-805/rc

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-805/coif). M.P. is an employee of Siemens Healthineers, Korea. U.G. and M.B.K. are developers at Siemens Healthineers, USA. All authors report nonfinancial technical support from Siemens Healthineers. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyung Hee University Hospital (No. 2023-12-032) for reviewing medical records. Individual consent for this retrospective study was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:329-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jang HJ, Min JH, Lee JE, Shin KS, Kim KH, Choi SY. Assessment of liver fibrosis with gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI: comparisons with transient elastography, ElastPQ, and serologic fibrosis markers. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:2769-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thiele M, Madsen BS, Hansen JF, Detlefsen S, Antonsen S, Krag A. Accuracy of the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Test vs FibroTest, Elastography, and Indirect Markers in Detection of Advanced Fibrosis in Patients With Alcoholic Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1369-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Beers BE, Pastor CM, Hussain HK. Primovist, Eovist: what to expect? J Hepatol 2012;57:421-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Wang X, Miao Y, Hu C, Zhao W. Liver function correlates with liver-to-portal vein contrast ratio during the hepatobiliary phase with Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MR at 3 Tesla. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018;43:2262-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bae KE, Kim SY, Lee SS, Kim KW, Won HJ, Shin YM, Kim PN, Lee MG. Assessment of hepatic function with Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced hepatic MRI. Dig Dis 2012;30:617-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bastati N, Wibmer A, Tamandl D, Einspieler H, Hodge JC, Poetter-Lang S, Rockenschaub S, Berlakovich GA, Trauner M, Herold C, Ba-Ssalamah A. Assessment of Orthotopic Liver Transplant Graft Survival on Gadoxetic Acid-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using Qualitative and Quantitative Parameters. Invest Radiol 2016;51:728-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoon JH, Lee JM, Paek M, Han JK, Choi BI. Quantitative assessment of hepatic function: modified look-locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) sequence for T1 mapping on Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced liver MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2016;26:1775-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassinotto C, Feldis M, Vergniol J, Mouries A, Cochet H, Lapuyade B, Hocquelet A, Juanola E, Foucher J, Laurent F, De Ledinghen V. MR relaxometry in chronic liver diseases: Comparison of T1 mapping, T2 mapping, and diffusion-weighted imaging for assessing cirrhosis diagnosis and severity. Eur J Radiol 2015;84:1459-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heye T, Yang SR, Bock M, Brost S, Weigand K, Longerich T, Kauczor HU, Hosch W. MR relaxometry of the liver: significant elevation of T1 relaxation time in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur Radiol 2012;22:1224-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomsen C, Christoffersen P, Henriksen O, Juhl E. Prolonged T1 in patients with liver cirrhosis: an in vivo MRI study. Magn Reson Imaging 1990;8:599-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamdy A, Kitagawa K, Ishida M, Sakuma H. Native Myocardial T1 Mapping, Are We There Yet? Int Heart J 2016;57:400-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banerjee R, Pavlides M, Tunnicliffe EM, Piechnik SK, Sarania N, Philips R, Collier JD, Booth JC, Schneider JE, Wang LM, Delaney DW, Fleming KA, Robson MD, Barnes E, Neubauer S. Multiparametric magnetic resonance for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver disease. J Hepatol 2014;60:69-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henninger B, Kremser C, Rauch S, Eder R, Zoller H, Finkenstedt A, Michaely HJ, Schocke M. Evaluation of MR imaging with T1 and T2* mapping for the determination of hepatic iron overload. Eur Radiol 2012;22:2478-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Ulmenstein S, Bogdanovic S, Honcharova-Biletska H, Blümel S, Deibel AR, Segna D, Jüngst C, Weber A, Kuntzen T, Gubler C, Reiner CS. Assessment of hepatic fibrosis and inflammation with look-locker T1 mapping and magnetic resonance elastography with histopathology as reference standard. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2022;47:3746-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoad CL, Palaniyappan N, Kaye P, Chernova Y, James MW, Costigan C, Austin A, Marciani L, Gowland PA, Guha IN, Francis ST, Aithal GP. A study of T1 relaxation time as a measure of liver fibrosis and the influence of confounding histological factors. NMR Biomed 2015;28:706-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kellman P, Bandettini WP, Mancini C, Hammer-Hansen S, Hansen MS, Arai AE. Characterization of myocardial T1-mapping bias caused by intramyocardial fat in inversion recovery and saturation recovery techniques. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015;17:33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mozes FE, Tunnicliffe EM, Pavlides M, Robson MD. Influence of fat on liver T1 measurements using modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) methods at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging 2016;44:105-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higashi M, Tanabe M, Yamane M, Keerthivasan MB, Imai H, Yonezawa T, Nakamura M, Ito K. Impact of fat on the apparent T1 value of the liver: assessment by water-only derived T1 mapping. Eur Radiol 2023;33:6844-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang A, Tan J, Sun M, Hamilton G, Bydder M, Wolfson T, Gamst AC, Middleton M, Brunt EM, Loomba R, Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Sirlin CB. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: MR imaging of liver proton density fat fraction to assess hepatic steatosis. Radiology 2013;267:422-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deichmann R. Fast high-resolution T1 mapping of the human brain. Magn Reson Med 2005;54:20-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leporq B, Ratiney H, Pilleul F, Beuf O. Liver fat volume fraction quantification with fat and water T1 and T 2* estimation and accounting for NMR multiple components in patients with chronic liver disease at 1.5 and 3.0 T. Eur Radiol 2013;23:2175-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mozes FE, Tunnicliffe EM, Moolla A, Marjot T, Levick CK, Pavlides M, Robson MD. Mapping tissue water T(1) in the liver using the MOLLI T(1) method in the presence of fat, iron and B(0) inhomogeneity. NMR Biomed 2019;32:e4030. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamada A, Hara T, Li F, Fujinaga Y, Ueda K, Kadoya M, Doi K. Quantitative evaluation of liver function with use of gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 2011;260:727-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strasberg SM, Belghiti J, Clavien PA, Gadzijev E, Garden JO, Lau WY, Makuuchi M, Strong RW. The Brisbane 2000 Terminology of Liver Anatomy and Resections. HPB 2000;2:333-9.

- Yoon JH, Lee JM, Han JK, Choi BI. Shear wave elastography for liver stiffness measurement in clinical sonographic examinations: evaluation of intraobserver reproducibility, technical failure, and unreliable stiffness measurements. J Ultrasound Med 2014;33:437-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kudo M, Zheng RQ, Kim SR, Okabe Y, Osaki Y, Iijima H, Itani T, Kasugai H, Kanematsu M, Ito K, Usuki N, Shimamatsu K, Kage M, Kojiro M. Diagnostic accuracy of imaging for liver cirrhosis compared to histologically proven liver cirrhosis. A multicenter collaborative study. Intervirology 2008;51:17-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haimerl M, Verloh N, Zeman F, Fellner C, Nickel D, Lang SA, Teufel A, Stroszczynski C, Wiggermann P. Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI for evaluation of liver function: Comparison between signal-intensity-based indices and T1 relaxometry. Sci Rep 2017;7:43347. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katsube T, Okada M, Kumano S, Hori M, Imaoka I, Ishii K, Kudo M, Kitagaki H, Murakami T. Estimation of liver function using T1 mapping on Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol 2011;46:277-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamimura K, Fukukura Y, Yoneyama T, Takumi K, Tateyama A, Umanodan A, Shindo T, Kumagae Y, Ueno S, Koriyama C, Nakajo M. Quantitative evaluation of liver function with T1 relaxation time index on Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI: comparison with signal intensity-based indices. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014;40:884-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn JH, Yu JS, Park KS, Kang SH, Huh JH, Chang JS, Lee JH, Kim MY, Nickel MD, Kannengiesser S, Kim JY, Koh SB. Effect of hepatic steatosis on native T1 mapping of 3T magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of T1 values for patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Magn Reson Imaging 2021;80:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fellner C, Nickel MD, Kannengiesser S, Verloh N, Stroszczynski C, Haimerl M, Luerken L. Water-Fat Separated T1 Mapping in the Liver and Correlation to Hepatic Fat Fraction. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023.

- Gold GE, Han E, Stainsby J, Wright G, Brittain J, Beaulieu C. Musculoskeletal MRI at 3.0 T: relaxation times and image contrast. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:343-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoon JH, Lee JM, Kim E, Okuaki T, Han JK. Quantitative Liver Function Analysis: Volumetric T1 Mapping with Fast Multisection B(1) Inhomogeneity Correction in Hepatocyte-specific Contrast-enhanced Liver MR Imaging. Radiology 2017;282:408-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klaus JB, Goerke U, Klarhöfer M, Keerthivasan MB, Jung B, Berzigotti A, Ebner L, Roos J, Christe A, Obmann VC, Huber AT. MRI Dixon Fat-Corrected Look-Locker T1 Mapping for Quantification of Liver Fibrosis and Inflammation-A Comparison With the Non-Fat-Corrected Shortened Modified Look-Locker Inversion Recovery Technique. Invest Radiol 2024;59:754-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Besa C, Bane O, Jajamovich G, Marchione J, Taouli B 3D. T1 relaxometry pre and post gadoxetic acid injection for the assessment of liver cirrhosis and liver function. Magn Reson Imaging 2015;33:1075-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JE, Kim HO, Bae K, Choi DS, Nickel D. T1 mapping for liver function evaluation in gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging: comparison of look-locker inversion recovery and B(1) inhomogeneity-corrected variable flip angle method. Eur Radiol 2019;29:3584-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haimerl M, Verloh N, Zeman F, Fellner C, Müller-Wille R, Schreyer AG, Stroszczynski C, Wiggermann P. Assessment of clinical signs of liver cirrhosis using T1 mapping on Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced 3T MRI. PLoS One 2013;8:e85658. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haimerl M, Fuhrmann I, Poelsterl S, Fellner C, Nickel MD, Weigand K, Dahlke MH, Verloh N, Stroszczynski C, Wiggermann P. Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced T1 relaxometry for assessment of liver function determined by real-time (13)C-methacetin breath test. Eur Radiol 2018;28:3591-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldberg HI, Moss AA, Stark DD, McKerrow J, Engelstad B, Brito A. Hepatic cirrhosis: magnetic resonance imaging. Radiology 1984;153:737-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stark DD, Bass NM, Moss AA, Bacon BR, McKerrow JH, Cann CE, Brito A, Goldberg HI. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of experimentally induced liver disease. Radiology 1983;148:743-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Le Y, Dale B, Akisik F, Koons K, Lin C. Improved T1, contrast concentration, and pharmacokinetic parameter quantification in the presence of fat with two-point Dixon for dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 2016;75:1677-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang YT, Yeung HN, Carson PL, Ellis JH. Experimental analysis of T1 imaging with a single-scan, multiple-point, inversion-recovery technique. Magn Reson Med 1992;25:337-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meloni A, Carnevale A, Gaio P, Positano V, Passantino C, Pepe A, Barison A, Todiere G, Grigoratos C, Novani G, Pistoia L, Giganti M, Cademartiri F, Cossu A. Liver T1 and T2 mapping in a large cohort of healthy subjects: normal ranges and correlation with age and sex. MAGMA 2024;37:93-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavlides M, Banerjee R, Sellwood J, Kelly CJ, Robson MD, Booth JC, Collier J, Neubauer S, Barnes E. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging predicts clinical outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease. J Hepatol 2016;64:308-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]