Prospective comparisons of three interpretation methods of fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) has become the leading cause of death in developed countries, and the incidence and mortality of CHD in China are increasing. According to the 2017 to March 2020 data of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [comprising CHD, heart failure (HF), stroke, and hypertension] in adults ≥20 years of age is 48.6% overall (1). Therefore, exploring precise diagnosis and treatment methods, optimizing treatment strategies, and enabling early diagnosis of CHD are urgently needed. In recent years, coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) has been established as a noninvasive imaging modality for assessing CHD. However, CCTA does not always indicate myocardial ischemia in the presence of an obstructive artery (2). In addition, fractional flow reserve (FFR) has become the current standard for evaluating functional coronary stenosis (2). FFR refers to the maximum myocardial blood flow in a narrowed area, divided by normal maximum blood flow in that same area in the hypothetical case that the supplying coronary artery would be completely normal. In clinical practice, adenosine and other vasodilators are used to induce maximum congestion in myocardial microcirculation. FFR is assessed by measuring the ratio of the mean pressure (Pd) in the distal narrowed coronary artery to the mean pressure (Pa) in the aortic opening of the coronary artery using a pressure wire. FFR ≤0.80 is the reference standard for diagnosing myocardial ischemia. However, measurement of FFR is a costly, invasive procedure. Therefore, FFR derived from computed tomography (CT-FFR) has become a novel method for functional evaluation of non-invasive coronary stenosis, which is expected to achieve a “one-stop” method of non-invasive coronary anatomy and functional evaluation (3,4). In addition, recently, development in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and modeling have allowed more precise and faster estimation of coronary blood flow and pressure from CCTA datasets.

The selection of CT-FFR calculation locations is of particular importance when determining ischemic lesions for guiding therapeutic strategies. Most of the early studies, including the Prospective LongitudinAl Trial of FFRct: Outcome and Resource IMpacts (PLATFORM) (5) and the Assessing Diagnostic Value of Non-invasive FFRCT in Coronary Care (ADVANCE) (6), used the lowest CT-FFR values, which had high sensitivity but low specificity (7). In later studies, although CT-FFR was measured at the distal 2–3 cm of the lesion and remained consistent with the invasive FFR measurement location as far as possible, it was still difficult to ensure that the value was taken at the same point as the invasive FFR pressure guide wire. It is particularly important to find a precise CT-FFR calculation method that does not depend on the location of the invasive pressure guide wire. In recent years, some CT-FFR-related derivative indicators have emerged, such as lesion-specific CT-FFR (the value within 2 cm distal to the greatest stenotic lesion) and ΔCT-FFR (a difference of CT-FFR value between distal and proximal to anatomical stenosis), which do not depend on the position of invasive FFR pressure guide wire. Several retrospective studies have confirmed that such related derivative indicators have higher specificity in the detection of lesion-specific ischemia (8-14), indicating that they are more conducive to the early screening of functional ischemic stenosis. However, there has been no prospective research comparing different measured locations of CT-FFR. Therefore, we designed this prospective study to compare the diagnostic performance of three methods of CT-FFR (vessel-level CT-FFR, lesion-specific CT-FFR, and ΔCT-FFR) with invasive FFR as the reference standard to further explore the more precise location of CT-FFR measurement. We present this article in accordance with the STARD reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-600/rc).

Methods

Study design and population

This study was a prospective, single-center trial conducted in China that compared the diagnostic performance of three interpretation methods of CT-FFR calculation on an optimized CFD algorithm for the hemodynamic significance of coronary stenosis. CCTA and CT-FFR analyses were performed before invasive FFR measurement in a blind fashion. The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang Hospital [No. 2018(23K)]. All patients provided written informed consent. Consecutive participants who underwent CCTA with CT-FFR analysis followed by invasive FFR measurement in Zhejiang Hospital between January 2019 and June 2021 were included. Patients were not eligible if they had undergone prior stent implantation or coronary bypass surgery in the target artery, allergy to the contrast agent, nitrates, or adenosine, suspicion of acute coronary syndrome, chronic kidney disease [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 mL/kg/1.73 m2], severe HF, or were pregnant. The CCTA inclusion criteria were as follows: ≥1 stenosis with percent diameter stenosis between 40% and 70% in a vessel with diameter ≥2.0 mm. The CCTA exclusion criteria were as follows: significant arrhythmia, poor image quality. The angiographic exclusion criteria were as follows: ostial lesions, bifurcation lesions, severe vessel tortuosity, and vessel overlap. The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1. In addition, the study was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn); the trial registration number was ChiCTR2000034248, through which the trial protocol can be accessed.

CCTA acquisition and analysis

CCTA was performed using a dual-source computed tomography (CT) scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). All patients underwent breath-holding training before the examination, and their heart rate was controlled below 60 beats/minute as far as possible to avoid artifacts affecting image quality. Iopromide (350 mgI/mL) was used as a contrast agent, with an injection rate of 4 mL/s and the total amount was about 40–50 mL. At the same time, about 40 mL of physiological saline was injected after the contrast agent was injected. According to the actual situation, different electrocardiogram (ECG) gating technology was adopted to obtain the original image, mainly using prospective ECG gating technology, and using Siemens post-processing workstation to further process the image. CCTA scanning protocols were performed with a tube voltage of 120 kVp, tube current of 400 mAs, gantry rotation time of 330 ms, detector collimation of 32×0.6 mm combined with z-flying focal spot technology, and a craniocaudal scan direction. CCTA images were reconstructed with an increment of 0.5 mm. All images were analyzed independently by two senior attending radiologists in a blinded fashion. If these two physicians disagreed, a third, more senior radiologist (associate chief or chief) would re-analyze the images and make a decision.

ICA and FFR measurement

Standard protocols were followed for the measurement of invasive coronary angiography (ICA) and FFR. FFR was measured with a 0.014-inch pressure sensor-tipped guide wire (Pressure Wire; St Jude Medical Systems, St. Paul, MN, USA). To measure FFR, a pressure sensor guide wire was placed at 2–3 cm of the distal end of the stenotic lesion after zeroing and equalizing the aortic pressure. To induce maximum hyperemia of the coronary microvascular system, the concentration of intravenous adenosine triphosphate was 150–180 µg/kg/min. After getting the maximum hyperemia of the coronary microvascular system, the distal coronary artery pressure at the pressure sensor (Pd) and the proximal pressure at the coronary ostium (Pa) was recorded. FFR was the ratio of Pd to Pa, and the FFR value ≤0.80 was considered myocardial ischemia.

Three CT-FFR calculation methods

We used a novel CFD-based model (AccuFFRct, ArteryFlow Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) which has obtained Conformite Europeenne (CE) certification and China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) medical device registration certificate, and has undergone a prospective, multicenter validation clinical trial involving 339 cases (15), as well as multiple retrospective validation clinical studies (16,17). Clinical trials have demonstrated that, compared to invasive wire-based measurement of FFR, the AccuFFRct software calculates FFR values with an accuracy of around 90%. AccuFFRct can shorten the calculation time of CT-FFR while improving the diagnostic performance by incorporating patient-specific physiological parameters such as blood pressure and age into the algorithm optimization described in our study (17).

Firstly, we reconstructed a patient-specific three-dimensional (3D) anatomical model including the coronary tree, aorta, and heart from CCTA data semi-automatically. In the process of model reconstruction, a convolutional neural network (CNN)-based algorithm was used to segment the coronary artery, a U-Net based model was used to segment the aortic image, and the Mask R-CNN segmentation method was used to extract the left ventricle. The final anatomical model was reconstructed according to the optimized vessel boundary. Then, we preprocessed the 3D segmentation geometric model, and divided it into a mesh model. Next, the volume mesh model of the coronary artery tree was generated by the finite volume method of CFD simulation. The total coronary flow was calculated from the left ventricular myocardial mass, which could be easily obtained from the cardiac volume extracted by CCTA. The mean flow rate and aortic pressure relationships between baseline and hyperemic values were established and used for the assessment of hyperemia. For the outlet, the lumen diameter of each outlet vessel was used to determine the blood flow distribution according to Murray’s law. The arterial wall was assumed to be rigid with no-slip boundary conditions. In CFD simulations, blood was simulated as an incompressible viscous Newtonian fluid (density ρ=1,056 kg/m3, viscosity µ=0.0035 Pa·s). Numerical results of the coronary flow and pressure fields can be obtained and visualized on a 3D anatomical model by solving the Navier-Stokes equations on a standard desktop workstation. AccuFFRct values were calculated as the ratio of the distal pressure at the FFR measurement point to the aortic pressure. The simulation time for each case was approximately 35 minutes using standard operating procedures, including 3D coronary reconstruction and CFD calculations using AccuFFRct software (17).

The vessel-level AccuFFRct was the AccuFFRct value corresponding to the measurement point where the invasive FFR pressure guide wire sensor was placed distal to the stenosis of the target diseased vessel. The lesion-specific AccuFFRct value was measured at the distal 2 cm of the maximum stenosis adjacent to the target vessel. The ΔAccuFFRct value was the difference between AccuFFRct measured at the proximal and distal points adjacent to the maximum stenosis of the target lesion vessel (Figure 2).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range according to the data distribution, and categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used for correlation analysis between CT-FFR and invasive FFR, and the Bland-Altman method was used for consistency analysis. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct for the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia were calculated using invasive FFR ≤0.8 as the reference standard. NPV, PPV, diagnostic accuracy, and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were plotted by MedCalc statistical software (MedCalc, Ostend, Belgium) based on per-patient and per-vessel basis, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) was also calculated, and the Delong test was used to compare the AUC values. The vessel-level AccuFFRct ≤0.8 and lesion-specific AccuFFRct ≤0.8 were defined as myocardial ischemia (7). The optimal threshold of the ΔAccuFFRct value was defined as the value corresponding to the maximum Youden index in the ROC curve. We conducted subgroup analyses according to CCTA stenosis and coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of diagnostic efficiency of vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct. A multivariate logistic regression model that included factors identified as potentially significant (P<0.15) in the univariate analysis was used to analyze the factors influencing inconsistency between vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, ΔAccuFFRct, and invasive FFR. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient and lesion characteristics

A total of 124 patients (70.2% men, mean age 67±9 years) with 143 vessels were prospectively enrolled, and there were 83 (66.9%) patients with hypertension, 19 (15.3%) patients with hyperlipidemia, and 30 (24.2%) patients with diabetes. Among the 143 vessels, the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) accounted for 92 (64.3%) of the total lesion vessels. The baseline data of patients’ and lesions’ characteristics are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Data |

|---|---|

| Male | 87 (70.2) |

| Age (years) | 67±9 |

| Height (cm) | 165.13±7.30 |

| Weight (kg) | 67.06±11.66 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.31 [21.95–26.78] |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 134 [125–148] |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76±10 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 72 [65–80] |

| Laboratory profiles | |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.465 [0.993–1.820] |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.233 [3.448–5.015] |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.100 [0.940–1.270] |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.455 [1.7625–3.14] |

| TG/HDL-C | 1.383 [0.831–1.971] |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 72 [62–82] |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 92.668±20.800 |

| Risk factors | |

| Current smoking | 52 (41.9) |

| Hypertension | 83 (66.9) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 19 (15.3) |

| Diabetes | 30 (24.2) |

| History of stroke | 14 (11.3) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 42 (33.9) |

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation values or median [interquartile range] values, and categorize variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Scr, serum creatinine; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Table 2

| Characteristics | Data |

|---|---|

| Lesion location | |

| LAD | 92 (64.3) |

| LCX | 18 (12.6) |

| RCA | 33 (23.1) |

| FFR | 0.83 (0.75–0.87) |

| FFR ≤0.8 | 61 (42.7) |

| Vessel-level AccuFFRct | 0.82 (0.75–0.87) |

| Vessel-level AccuFFRct ≤0.8 | 66 (46.2) |

| Lesion-specific AccuFFRct | 0.85 (0.78–0.91) |

| Lesion-specific AccuFFRct ≤0.8 | 44 (30.8) |

| ΔAccuFFRct | 0.08 (0.04–0.12) |

| ΔAccuFFRct ≥0.105 | 44 (30.8) |

| CCTA stenosis ≥50% | 99 (69.2) |

| Coronary artery calcium score | 86.8 (3.5–187.8) |

| <100 | 74 (51.7) |

| 100–400 | 56 (39.2) |

| >400 | 13 (9.1) |

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) values, and categorize variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). ΔAccuFFRct, the difference between AccuFFRct measured at the proximal and distal points adjacent to the maximum stenosis of the target lesion vessel; AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; FFR, fractional flow reserve; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

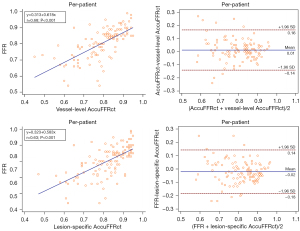

Correlation and consistency analysis of vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and invasive FFR

Vessel-level AccuFFRct demonstrated a moderate correlation with invasive FFR (r = 0.70 and r=0.68, P<0.001) on a per-vessel basis and per-patient basis. Bland-Altman analysis showed good consistency between vessel-level AccuFFRct and invasive FFR on both a per-patient basis [mean difference: 0.01±0.08, 95% limits of agreement (LOA): −0.14 to 0.16] and a per-vessel basis (mean difference: 0.01±0.07, 95% LOA: −0.13 to 0.16) (Figures 3,4).

Spearman correlation coefficients of lesion-specific AccuFFRct and invasive FFR on a per-vessel basis and a per-patient basis were 0.66 (P<0.001) and 0.63 (P<0.001), respectively. The good agreement between lesion-specific AccuFFRct and invasive FFR was also found on both a per-patient basis (mean difference: −0.02±0.08, 95% LOA: −0.18 to 0.14) and a per-vessel basis (mean difference: −0.02±0.08, 95% LOA: −0.18 to 0.14) (Figures 3,4).

Diagnostic performance of vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct on myocardial ischemia

On a per-vessel basis, with invasive FFR ≤0.8 as the reference standard for the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, diagnostic accuracy, and AUC values of CCTA, vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct in the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia were 82.0%, 40.2%, 50.5%, 75.0%, 58.0%, 0.611; 93.4%, 89.0%, 86.4%, 94.8%, 90.9%, 0.937; 62.3%, 92.7%, 86.4%, 76.8%, 79.7%, 0.880; and 62.3%, 92.7%, 86.4%, 76.8%, 79.7%, 0.854, respectively (Table 3). On a per-patient basis, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, diagnostic accuracy, and AUC values of CCTA, vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct in the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia were 84.5%, 34.8%, 53.3%, 71.9%, 58.1%, 0.597; 93.1%, 87.9%, 87.1%, 93.5%, 90.3%, 0.927; 62.1%, 92.4%, 87.8%, 73.5%, 78.2%, 0.884, and 65.5%, 92.4%, 88.4%, 75.3%, 79.8%, 0.873, respectively (Table 4).

Table 3

| Diagnostic characteristics | CCTA | Vessel-level AccuFFRct | Lesion-specific AccuFFRct | ΔAccuFFRct |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True positive | 50 | 57 | 38 | 38 |

| True negative | 33 | 73 | 76 | 76 |

| False positive | 49 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| False negative | 11 | 4 | 23 | 23 |

| Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | 82.0 (70.5–89.6) | 93.4 (84.3–97.4) | 62.3 (49.7–73.4) | 62.3 (49.7–73.4) |

| Specificity (%) (95% CI) | 40.2 (30.3–51.1) | 89.0 (80.4–94.1) | 92.7 (84.9–96.6) | 92.7 (84.9–96.6) |

| PPV (%) (95% CI) | 50.5 (40.8–60.1) | 86.4 (76.1–92.7) | 86.4 (73.3–93.6) | 86.4 (73.3–93.6) |

| NPV (%) (95% CI) | 75.0 (60.6–85.4) | 94.8 (87.4–98) | 76.8 (67.5–84) | 76.8 (67.5–84) |

| Accuracy (%) (95% CI) | 58.0 (49.8–65.8) | 90.9 (85.1–94.6) | 79.7 (72.4–85.5) | 79.7 (72.4–85.5) |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.611 (0.526–0.691) | 0.937 (0.884–0.971) | 0.880 (0.815–0.928) | 0.854 (0.785–0.907) |

ΔAccuFFRct, the difference between AccuFFRct measured at the proximal and distal points adjacent to the maximum stenosis of the target lesion vessel; AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; AUC, area under the curve; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Table 4

| Diagnostic characteristic | CCTA | Vessel-level AccuFFRct | Lesion-specific AccuFFRct | ΔAccuFFRct |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True positive | 49 | 54 | 36 | 38 |

| True negative | 23 | 58 | 61 | 61 |

| False positive | 43 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| False negative | 9 | 4 | 22 | 20 |

| Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | 84.5 (73.1–91.6) | 93.1 (83.6–97.3) | 62.1 (49.2–73.4) | 65.5 (52.7–76.4) |

| Specificity (%) (95% CI) | 34.8 (24.5–46.9) | 87.9 (77.9–93.7) | 92.4 (83.5–96.7) | 92.4 (83.5–96.7) |

| PPV (%) (95% CI) | 53.3 (43.1–63.1) | 87.1 (76.6–93.3) | 87.8 (74.5–94.7) | 88.4 (75.5–94.9) |

| NPV (%) (95% CI) | 71.9 (54.6–84.4) | 93.5 (84.6–97.5) | 73.5 (63.1–81.8) | 75.3 (64.9–83.4) |

| Accuracy (%) (95% CI) | 58.1 (49.3–66.4) | 90.3 (83.8–94.4) | 78.2 (70.2–84.6) | 79.8 (71.9–86) |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.597 (0.505–0.684) | 0.927 (0.867–0.966) | 0.884 (0.814–0.934) | 0.873 (0.802–0.926) |

ΔAccuFFRct, the difference between AccuFFRct measured at the proximal and distal points adjacent to the maximum stenosis of the target lesion vessel; AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; AUC, area under the curve; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Subgroup analyses according to CCTA stenosis and CAC score of diagnostic efficiency of vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct showed that in a group with CCTA <50%, the AUCs of vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct were 0.934, 0.862, and 0.822 and those in the group with CCTA ≥50% were 0.938, 0.881, and 0.838, respectively. In addition, the AUCs of vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct were 0.951, 0.885, and 0.816 and 0.918, 0.870, and 0.880 among groups of CACs <100 and CACs ≥100, respectively (Table 5 and Figure 5).

Table 5

| Methods | CCTA stenosis | Coronary artery calcium score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50% (N=44) | ≥50% (N=99) | <100 (N=74) | ≥100 (N=69) | ||

| Vessel-level AccuFFRct | 0.934 (0.816–0.987) | 0.938 (0.871–0.976) | 0.951 (0.874–0.987) | 0.918 (0.827–0.97) | |

| Lesion-specific AccuFFRct | 0.862 (0.725–0.947) | 0.881 (0.800–0.937) | 0.885 (0.789–0.947) | 0.870 (0.767–0.939) | |

| ΔAccuFFRct | 0.822 (0.678–0.921) | 0.838 (0.751–0.905) | 0.816 (0.709–0.897) | 0.880 (0.779–0.946) | |

Data are expressed as AUC (95% CI). ΔAccuFFRct, the difference between AccuFFRct measured at the proximal and distal points adjacent to the maximum stenosis of the target lesion vessel; AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; AUC, area under the curve; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CI, confidence interval.

The multivariate logistic analysis for independent factors influencing inconsistency between vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, ΔAccuFFRct, and invasive FFR

To explore the factors of hemodynamics and lesion characteristics that influenced discordance between vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, ΔAccuFFRct, and invasive FFR, the patients were divided into a consistent group and inconsistent group according to their respective cutoff values.

Tables 6-8 show the baseline characteristics of the consistent and inconsistent groups between vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, ΔAccuFFRct, and invasive FFR, respectively. Table 6 showed that serum creatinine level in the inconsistent group of vessel-level AccuFFRct and invasive FFR was significantly higher than that in the consistent group. The discordance between ΔAccuFFRct and invasive FFR was present significantly more often in men (P=0.029).

Table 6

| Characteristics | Consistent groups (N=112) | Inconsistent groups (N=12) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 76 (67.9) | 11 (91.7) | 0.087 |

| Age (years) | 67±9 | 66±9 | 0.843 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.31 (21.66–26.59) | 25.61±3.15 | 0.308 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 134 (125–147) | 137±19 | 0.813 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76±10 | 77±9 | 0.643 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 73 (66–80) | 73±14 | 0.523 |

| hCRP (mg/L) | 1.08 (0.80–3.17) | 1.03 (0.51–2.85) | 0.608 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.40 (0.99–1.82) | 1.70±0.85 | 0.512 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.23 (3.45–5.02) | 4.25±1.03 | 0.823 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.46 (1.75–3.14) | 2.56±0.76 | 0.648 |

| TG/HDL-C | 1.38 (0.81–1.97) | 1.60±0.90 | 0.642 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.31 (4.64–5.95) | 5.38 (4.35–6.29) | 0.784 |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 70.50 (61.25–81.75) | 84.17±17.07 | 0.031 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 93.42±20.75 | 85.66±20.86 | 0.221 |

| Current smoker | 47 (42.0) | 5 (41.7) | 0.984 |

| Drinking history | 31 (27.7) | 5 (41.7) | 0.310 |

| Hypertension | 75 (67.0) | 8 (66.7) | 0.983 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 19 (17.0) | 0 | 0.121 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (23.2) | 4 (33.3) | 0.437 |

| Stroke | 13 (11.6) | 1 (8.3) | 0.733 |

| Peripheral arteriosclerosis obliterations | 39 (34.8) | 3 (25.0) | 0.494 |

| CCTA stenosis degree ≥50% | 83 (74.1) | 9 (75.0) | 0.946 |

| Coronary artery calcium score ≥100 | 55 (49.1) | 6 (50.0) | 0.953 |

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation values or median (interquartile range) values, and categorize variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; BMI, body mass index; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FFR, fractional flow reserve; hCRP, hypersensitive C-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Scr, serum creatinine; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Table 7

| Characteristics | Consistent groups (N=97) | Inconsistent groups (N=27) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 66 (68.0) | 21 (77.8) | 0.328 |

| Age (years) | 67±9 | 66±7 | 0.453 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.31 (21.98–26.93) | 23.93±2.69 | 0.453 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 134 (125–148) | 132 (126–155) | 0.785 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75±10 | 79±10 | 0.121 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 75±13 | 71±11 | 0.222 |

| hCRP (mg/L) | 1.20 (0.80–3.39) | 0.90 (0.72–1.43) | 0.108 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.40 (0.99–1.85) | 1.49±0.60 | 0.923 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.20 (3.36–4.99) | 4.46±1.03 | 0.289 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.40 (1.72–3.14) | 2.59±0.80 | 0.377 |

| TG/HDL-C | 1.39 (0.83–2.15) | 1.30±0.66 | 0.288 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.31 (4.69–5.93) | 5.40 (4.50–6.30) | 0.966 |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 70.00 (61.5–82.00) | 76.44±16.12 | 0.220 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 93.33±21.93 | 90.31±16.22 | 0.507 |

| Current smoker | 41 (42.3) | 11 (40.7) | 0.887 |

| Drinking history | 25 (25.8) | 11 (40.7) | 0.130 |

| Hypertension | 62 (63.9) | 21 (77.8) | 0.176 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 17 (17.5) | 2 (7.4) | 0.197 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (26.8) | 4 (14.8) | 0.198 |

| Stroke | 12 (12.4) | 2 (7.4) | 0.471 |

| Peripheral arteriosclerosis obliterations | 36 (37.1) | 6 (22.2) | 0.148 |

| CCTA stenosis degree ≥50% | 70 (72.2) | 22 (81.5) | 0.328 |

| Coronary artery calcium score ≥100 | 48 (49.5) | 13 (48.1) | 0.902 |

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation values or median (interquartile range) values, and categorize variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; BMI, body mass index; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FFR, fractional flow reserve; hCRP, hypersensitive C-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Scr, serum creatinine; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Table 8

| Characteristics | Consistent groups (N=99) | Inconsistent groups (N=25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 65 (65.7) | 22 (88.0) | 0.029 |

| Age (years) | 67±9 | 66±7 | 0.862 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.31 (21.93–26.81) | 23.93±2.69 | 0.842 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 134 (125–150) | 138±20 | 0.667 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75±10 | 76 (71–80) | 0.725 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 75±13 | 71±11 | 0.395 |

| hCRP (mg/L) | 1.13 (0.80–3.23) | 1.01 (0.76–2.20) | 0.497 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.40 (0.97–1.87) | 1.49±0.60 | 0.281 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.27 (3.33–5.06) | 4.46±1.03 | 0.960 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.09 (0.94–1.27) | 1.27±0.36 | 0.820 |

| TG/HDL-C | 2.39 (1.70–3.14) | 2.59±0.80 | 0.665 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 1.368 (0.772–1.977) | 1.392 (1.135–1.950) | 0.499 |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 5.30 (4.62–5.95) | 5.64±1.59 | 0.474 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 93.33±21.94 | 90.31±16.22 | 0.068 |

| Current smoker | 39 (39.4) | 13 (52.0) | 0.254 |

| Drinking history | 27 (27.3) | 9 (36.0) | 0.390 |

| Hypertension | 65 (65.7) | 18 (72.0) | 0.547 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 17 (17.2) | 2 (8.0) | 0.255 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 25 (25.3) | 5 (20.0) | 0.584 |

| Stroke | 12 (12.1) | 2 (8.0) | 0.561 |

| peripheral arteriosclerosis obliterations | 32 (32.3) | 10 (40.0) | 0.469 |

| CCTA stenosis degree ≥50% | 70 (70.7) | 22 (88.0) | 0.077 |

| Coronary artery calcium score ≥100 | 47 (47.5) | 14 (56.0) | 0.446 |

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation values or median (interquartile range) values, and categorize variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). ΔAccuFFRct, the difference between AccuFFRct measured at the proximal and distal points adjacent to the maximum stenosis of the target lesion vessel; AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; BMI, body mass index; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FFR, fractional flow reserve; hCRP, hypersensitive C-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Scr, serum creatinine; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that neither clinical characteristics nor lesion characteristics were independent influencing factors of the inconsistent diagnosis between vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, ΔAccuFFRct, and FFR (all P>0.05) (Table 9).

Table 9

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel-level AccuFFRct | |||

| Male | 1.689 | 0.304–9.400 | 0.549 |

| Scr | 0.980 | 0.949–1.011 | 0.203 |

| Lesion-specific AccuFFRct | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.975 | 0.930–1.022 | 0.292 |

| hCRP (mg/L) | 1.061 | 0.915–1.229 | 0.435 |

| Drinking history | 2.407 | 0.908–6.380 | 0.077 |

| Peripheral arteriosclerosis | 0.429 | 0.141–1.303 | 0.135 |

| ΔAccuFFRct | |||

| Man | 0.418 | 0.069–2.530 | 0.343 |

| Scr | 0.970 | 0.911–1.033 | 0.339 |

| eGFR | 0.969 | 0.920–1.020 | 0.225 |

| CCTA stenosis degree ≥50% | 0.644 | 0.230–1.803 | 0.402 |

ΔAccuFFRct, the difference between AccuFFRct measured at the proximal and distal points adjacent to the maximum stenosis of the target lesion vessel; AccuFFRct, fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FFR, fractional flow reserve; hCRP, hypersensitive C-reactive protein; OR, odds ratio; Scr, serum creatinine.

Discussion

The main findings of our study are summarized in the following: (I) both vessel-level AccuFFRct and lesion-specific AccuFFRct were highly correlated with invasive FFR with good consistency on a per-patient and per-vessel basis; (II) using invasive FFR ≤0.8 as the reference standard for myocardial ischemia, compared with CCTA, vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct can significantly improve the diagnostic efficiency of myocardial ischemia at both per-patient and per-vessel basis. The AUC value of vessel-level AccuFFRct was the highest among these three methods, whereas lesion-specific AccuFFRct and ΔAccuFFRct had higher specificity than vessel-level AccuFFRct. Further subgroup analyses showed that ΔAccuFFRct was more effective in the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia with high calcification score than those with low calcification score; (III) multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that neither clinical characteristics nor lesion characteristics were independent influencing factors for the inconsistent diagnosis between vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, ΔAccuFFRct, and FFR (all P>0.05).

The results of this study showed that AccuFFRct significantly improved diagnostic specificity compared to CCTA, which is consistent with latest studies (16-18). Vessel-level AccuFFRct showed good diagnostic accuracy at both per-patient (AUC =0.927) and per-vessel basis (AUC =0.937), compared with the Chinese Multicenter Study (18) (per-vessel AUC =0.92; per-patient AUC =0.92) and the latest study by Jiang et al. (16) (per-vessel AUC =0.927; per-patient AUC =0.935). Furthermore, vessel-level AccuFFRct showed higher diagnostic accuracy (90.9%) consist with the Chinese Multicenter Study (0.91) (18). Both correlation and consistency analysis showed high correlation and consistency between vessel-level AccuFFRct and invasive FFR on a per-vessel basis, comparable to the Jiang et al.’s study (r=0.65) (16). The good diagnostic performance of our CT-FFR calculation methods was preliminarily verified.

The selection of CT-FFR measurement location was of particular importance when determining ischemic lesions or guiding therapeutic strategies. CT-FFR could provide FFR values of the entire coronary tree at any location, therefore, the values of the distal stenosis lesion and the farthest coronary tree could be obtained. However, similar to invasive FFR, for vessels without coronary artery obstruction, even without focal stenosis, CT-FFR values would gradually decrease, and the CT-FFR difference from the coronary opening to the distal aspect was between 0.08 and 0.13 (7). For obstructive CHD, the CT-FFR value was usually lower than the invasive FFR value, with a deviation of 0.03–0.05 (7). Unlike invasive FFR, CT-FFR cannot accurately map the position of the FFR pressure guide wire sensor. Most of the early studies, including PLATFORM (5) and ADVANCE (6) studies, used the lowest CT-FFR value, which has high sensitivity but low specificity and may overestimate the degree of lesion ischemia (7). Researchers have suggested that it was not enough to only refer to the lowest CT-FFR value before ICA (19).

In recent years, some derivative indicators of CT-FFR, such as lesion-specific CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR have emerged. Kueh et al. (9) showed that lesion-specific CT-FFR could effectively reclassify 43.9% of the positive results of the lowest CT-FFR measured at distal vessel, especially in moderate stenosis. The incidence of ICA in lesion-specific CT-FFR-positive patients was significantly higher than that in the lowest CT-FFR-positive patients (35.8% vs. 29.3%, P<0.01). Similarly, the rate of revascularization at 60 days of follow-up in lesion-specific CT-FFR-positive patients was significantly higher in the lowest CT-FFR-positive patients (53% vs. 44%, P<0.01). In a retrospective study, Takagi et al. (12) compared the diagnostic performance of the lowest CT-FFR, lesion-specific CT-FFR, and ΔCT-FFR of 73 vessels in 50 patients with Heart Flow software (HeartFlow Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA). The results showed that 40 vessels (55%) were diagnosed as myocardial ischemia, and with invasive FFR as the reference standard, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and AUC values of the lowest CT-FFR were 90%, 39%, 67%, and 0.65, respectively; the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and AUC values of lesion-specific CT-FFR were 78%, 64%, 71%, and 0.71, respectively; the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and AUC values of ΔCT-FFR were 80%, 82%, 81%, and 0.86, respectively. The results showed that ΔCT-FFR has the highest AUC value among these three, suggesting that ΔCT-FFR has better diagnostic efficiency in myocardial ischemia than the lowest CT-FFR and lesion-specific CT-FFR. Recently, Yan et al. (14) compared the diagnostic performance of CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR in myocardial ischemia based on ML-based software (cFFR 3.0, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany). The results showed that compared with CCTA alone, both lesion-specific CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR could improve the diagnostic efficiency of myocardial ischemia, and ΔCT-FFR (AUC =0.803) had superior diagnostic efficiency than lesion-specific CT-FFR (AUC =0.743). These results suggested that lesion-specific CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR were also worthy of more attention in clinical application.

Takagi et al. (12) adopted the lowest CT-FFR (the value measured at the distal end of the coronary vessel) to compared with lesion-specific CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, diagnostic accuracy, and AUC values of the lowest CT-FFR were 90%, 39%, 64%, 77%, 67%, and 0.65, respectively. However, it was not completely reliable to diagnose myocardial ischemia simply using the lowest CT-FFR. Therefore, we calculated the vessel-level AccuFFRct, which corresponds to the measurement point of the invasive FFR pressure guide wire sensor at the distal end of the target vessel stenosis. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, diagnostic accuracy, and AUC values of vessel-level CT-FFR were 93.4%, 89%, 86.4%, 94.8%, 90.9%, and 0.937, respectively. Our results suggested that the diagnostic performance of vessel-level AccuFFRct might be superior to that of the lowest CT-FFR.

In this study, the specificity of lesion-specific AccuFFRct and ΔAccuFFRct was higher than that of vessel-level AccuFFRct (92.7% vs. 89.0%), which is consistent with previous research (14), suggesting that lesion-specific AccuFFRct was likely to improve the diagnostic specificity of myocardial ischemia. In addition, the AUC values of vessel-level AccuFFRct were higher than those of lesion-specific AccuFFRct and ΔAccuFFRct, both at per-vessel and per-patient basis, but the AUC values of all three were higher than 0.8, suggesting that all of them had good diagnostic accuracy. Previous studies have shown that ΔCT-FFR was superior to lesion-specific CT-FFR and the lowest CT-FFR (12), which was discordant with our study. However, in this study, the measurement location of vessel-level AccuFFRct was based on the position of the invasive FFR pressure guide wire sensor; it was objective that the CT-FFR values calculated by the CT-FFR computed model would decrease along the target vessel from proximal to distal, besides, the measurement location of lesion-specific AccuFFRct and ΔAccuFFRct were very close to the target vessel stenosis location, which may underestimate stenosis severity; therefore, it might lead to a high false negative value and partly affected the diagnostic accuracy.

Tesche et al. (20) reported that the performance of CT-FFR became significantly different as calcium burden/Agatston calcium score increased, the AUC was 0.71 versus 0.85 in the high Agatston scores (CAC ≥400) and in low-to-intermediate Agatston calcium scores (CAC >0 to <400), respectively. Lee et al. (10) showed that noninvasive hemodynamic assessment can improve the identification of high-risk plaques. Lee et al. (10) also confirmed that culprit vessels have lower CT-FFR and higher ΔCT-FFR compared with non-culprit vessels. In our study, we conducted subgroup analyses according to CAC score, which showed that the AUC value of ΔAccuFFRct was higher in the group with calcification score ≥100 (AUC =0.880) than in the group with calcification score <100 (AUC =0.816). The above research results suggest that ΔAccuFFRct may have higher diagnostic efficacy in identifying lesions with high calcification score.

The selection of CT-FFR calculation locations was of particular importance when determining ischemic lesions for guiding therapeutic strategies. CT-FFR-related derivative measurements do not need to rely on the position of the invasive FFR pressure guide wire; if we can validate the diagnostic efficiency of these derivative measurements, patients may be able to avoid undergoing invasive FFR measurement, which is not only more conducive on the early screening of functional stenosis but also helps to reduce costs. However, prospective, multi-center trials are needed to verify its diagnostic efficacy and further explore its impact on the long-term prognosis of patients.

Our study has some limitations. First, this study was a single-center study. Due to the limitations of the study time and the optimization process of the software algorithm, the final number of enrolled patients was small, and the statistical efficiency was partly limited. It is necessary to conduct multi-center study and further expand the sample size to verify the diagnostic efficiency of the domestic CT-FFR calculation software. It is conducive to the extensive application of CT-FFR in clinical practice in China and the realization of early accurate diagnosis and treatment for CHD patients. Second, this study was a cross-sectional study lacking follow-up of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs). Follow-up of events could be carried out in the future to verify the application of AccuFFRct on clinical decision-making and patient prognosis. Third, the plaque features were not quantitatively calculated in this study, so future studies need to add plaque features to further verify their impact on the diagnostic efficiency of CT-FFR and its derived indicators. Therefore, in the future, we will conduct prospective, multi-center trials, calculate coronary plaque information, and conduct the follow-up of MACEs events to further validate diagnostic efficiency, to enable better application to clinical practice.

Conclusions

With invasive FFR as the reference standard, vessel-level AccuFFRct and lesion-specific AccuFFRct demonstrated good correlation and consistency. Vessel-level AccuFFRct, lesion-specific AccuFFRct, and ΔAccuFFRct provided better diagnostic performance compared with CCTA, with vessel-level AccuFFRct being superior in predicting myocardial ischemia, wheres lesion-specific AccuFFRct and ΔAccuFFRct had higher specificity than vessel-level AccuFFRct. Lesion-specific CT-FFR, and ΔCT-FFR measurements do not rely on the position of the invasive FFR pressure guide wire, our study partially verified the diagnostic efficiency of them, suggesting that they were worth further research in clinical application.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this article has been presented in the 35th Great Wall International Congress of Cardiology Asian Heart Society Congress 2024.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STARD reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-600/rc

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-600/coif). Y.H., X.L. and J.X. are employees of ArteryFlow Technology Co., Ltd. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang Hospital [No. 2018(23K)]. All patients provided written informed consent.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147:e93-e621. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2020;41:407-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Min JK, Koo BK, Erglis A, Doh JH, Daniels DV, Jegere S, Kim HS, Dunning AM, Defrance T, Lansky A, Leipsic J. Usefulness of noninvasive fractional flow reserve computed from coronary computed tomographic angiograms for intermediate stenoses confirmed by quantitative coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:971-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou J, Yang JJ, Yang X, Chen ZY, He B, Du LS, Chen YD. Impact of Clinical Guideline Recommendations on the Application of Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography in Patients with Suspected Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:135-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Douglas PS, De Bruyne B, Pontone G, Patel MR, Norgaard BL, Byrne RA, et al. 1-Year Outcomes of FFRCT-Guided Care in Patients With Suspected Coronary Disease: The PLATFORM Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:435-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fairbairn TA, Nieman K, Akasaka T, Nørgaard BL, Berman DS, Raff G, et al. Real-world clinical utility and impact on clinical decision-making of coronary computed tomography angiography-derived fractional flow reserve: lessons from the ADVANCE Registry. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3701-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajiah P, Cummings KW, Williamson E, Young PM. CT Fractional Flow Reserve: A Practical Guide to Application, Interpretation, and Problem Solving. Radiographics 2022;42:340-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cami E, Tagami T, Raff G, Fonte TA, Renard B, Gallagher MJ, Chinnaiyan K, Bilolikar A, Fan A, Hafeez A, Safian RD. Assessment of lesion-specific ischemia using fractional flow reserve (FFR) profiles derived from coronary computed tomography angiography (FFRCT) and invasive pressure measurements (FFRINV): Importance of the site of measurement and implications for patient referral for invasive coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018;12:480-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kueh SH, Mooney J, Ohana M, Kim U, Blanke P, Grover R, Sellers S, Ellis J, Murphy D, Hague C, Bax JJ, Nørgaard BL, Rabbat M, Leipsic JA. Fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography reclassification rate using value distal to lesion compared to lowest value. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017;11:462-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JM, Choi G, Koo BK, Hwang D, Park J, Zhang J, et al. Identification of High-Risk Plaques Destined to Cause Acute Coronary Syndrome Using Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography and Computational Fluid Dynamics. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:1032-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Omori H, Hara M, Sobue Y, Kawase Y, Mizukami T, Tanigaki T, Hirata T, Ota H, Okubo M, Hirakawa A, Suzuki T, Kondo T, Leipsic J, Nørgaard BL, Matsuo H. Determination of the Optimal Measurement Point for Fractional Flow Reserve Derived From CTA Using Pressure Wire Assessment as Reference. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021;216:1492-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takagi H, Ishikawa Y, Orii M, Ota H, Niiyama M, Tanaka R, Morino Y, Yoshioka K. Optimized interpretation of fractional flow reserve derived from computed tomography: Comparison of three interpretation methods. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2019;13:134-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takagi H, Leipsic JA, McNamara N, Martin I, Fairbairn TA, Akasaka T, et al. Trans-lesional fractional flow reserve gradient as derived from coronary CT improves patient management: ADVANCE registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2022;16:19-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan H, Gao Y, Zhao N, Geng W, Hou Z, An Y, Zhang J, Lu B. Change in Computed Tomography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve Across the Lesion Improve the Diagnostic Performance of Functional Coronary Stenosis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021;8:788703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li C, Hu Y, Jiang J, Dong L, Sun Y, Tang L, Du C, Yin D, Jiang W, Leng X, Jiang F, Pan Y, Jiang X, Zhou Z, Koo BK, Xiang J, Wang J. ACCURATE-CT Investigators. Diagnostic Performance of Fractional Flow Reserve Derived From Coronary CT Angiography: The ACCURATE-CT Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2024;17:1980-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang J, Du C, Hu Y, Yuan H, Wang J, Pan Y, Bao L, Dong L, Li C, Sun Y, Leng X, Xiang J, Tang L, Wang J. Diagnostic performance of computational fluid dynamics (CFD)-based fractional flow reserve (FFR) derived from coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) for assessing functional severity of coronary lesions. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023;13:1672-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang W, Pan Y, Hu Y, Leng X, Jiang J, Feng L, Xia Y, Sun Y, Wang J, Xiang J, Li C. Diagnostic accuracy of coronary computed tomography angiography-derived fractional flow reserve. Biomed Eng Online 2021;20:77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang CX, Liu CY, Lu MJ, Schoepf UJ, Tesche C, Bayer RR 2nd, et al. CT FFR for Ischemia-Specific CAD With a New Computational Fluid Dynamics Algorithm: A Chinese Multicenter Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:980-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabbat MG, Berman DS, Kern M, Raff G, Chinnaiyan K, Koweek L, Shaw LJ, Blanke P, Scherer M, Jensen JM, Lesser J, Nørgaard BL, Pontone G, De Bruyne B, Bax JJ, Leipsic J. Interpreting results of coronary computed tomography angiography-derived fractional flow reserve in clinical practice. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017;11:383-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tesche C, Otani K, De Cecco CN, Coenen A, De Geer J, Kruk M, Kim YH, Albrecht MH, Baumann S, Renker M, Bayer RR, Duguay TM, Litwin SE, Varga-Szemes A, Steinberg DH, Yang DH, Kepka C, Persson A, Nieman K, Schoepf UJ. Influence of Coronary Calcium on Diagnostic Performance of Machine Learning CT-FFR: Results From MACHINE Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:760-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]