Association of aberrant brain network connectivity with visual dysfunction in patients with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: a pilot study

Introduction

Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) is the most common acute optic neuropathy in patients over 50 years old and has become the second most common cause of optic nerve-related vision loss in adults after glaucoma (1,2). This condition is typically characterized by a sudden, painless decrease in visual acuity (VA), along with visual field (VF) loss and optic nerve edema and may impact one eye or both eyes consecutively. Although the exact cause of NAION is unknown, it is generally believed to stem from an insufficient blood supply to the short posterior ciliary arteries that feed the optic nerve head, resulting in acute ischemic infarction of the optic nerve and subsequent inflammation and ultimately leading to degeneration of axons and the apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) (3). Studies have indicated that the incidence of NAION in the unaffected eye could reach 15% within 5 years of the first eye being affected (4). There are currently no consistently effective treatments for enhancing the vision in eyes affected by NAION, nor are there proven methods for preventing the involvement of the second eye (5). Hence, there is an urgent necessity to deepen our understanding of the disease’s pathophysiology to improve prognosis, identify potential therapeutic avenues, and ultimately enhance the vision-related quality of life of patients.

In the natural progression of NAION, some patients may experience spontaneous visual improvement despite persistent axonal dysfunction or loss in the optic nerve (6), potentially due to plasticity and functional reorganization of the visual system and higher brain centers (7,8). Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) of blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals serves as an effective tool for evaluating neuronal activity, particularly changes in functional brain networks, and has been extensively used in monitoring various ophthalmic conditions such as glaucoma, optic neuritis, strabismus, and amblyopia. Although studies using rs-fMRI to examine NAION have revealed irregularities in spontaneous brain activity among patients (9,10), the impact of anatomical and functional alterations on the functional cortical network and its relation to visual recovery remain largely unknown. Within this context, employing graph theoretic analysis can aid in characterizing the functional connectivity within extensive networks. This can generate a conceptual framework for quantifying intricate global and local patterns of network connectivity in the brain, thereby potentially providing valuable insights into the topology of human brain networks (11). Through this approach, our previous study identified that patients with NAION exhibit altered and repositioned brain connectivity hubs (12).

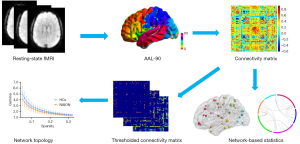

There is a scarcity of rs-fMRI studies focusing on NAION, and gaining insight into the regulation of brain activity could help in further clarifying the relevant pathological mechanisms and potentially improve the efficacy of treatment. This research project expands on our prior work by using graph theory analysis to identify topological variations in brain networks and changes in network connectivity among patients with NAION from a variety of perspectives. We hypothesized that individuals with NAION demonstrate disturbances in topological characteristics and modified network functional connectivity in comparison to healthy controls (HCs), with potential correlations with visual dysfunction. The overall framework of our study is shown in Figure 1. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-2062/rc).

Methods

Participants

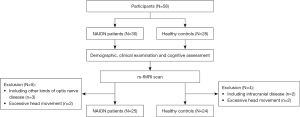

A total of 30 patients with NAION and 28 HCs treated at Dongfang Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, between March 2019 and April 2022 were initially enrolled in this prospective pilot study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Dongfang Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (No. 2017030202). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment in the study. Inclusion criteria for patients with NAION were as follows: (I) abrupt and painless decline in VA accompanied by optic disc edema; (II) VF defects related to the optic disc, mostly in the nasal and/or inferior regions; (III) the resolution of optic disc edema; (IV) no contraindications for MRI; and (V) right-handedness. The exclusion criteria included the following: (I) optic neuritis, giant cell arteritis, posterior ischemic optic neuropathy, or other optic nerve diseases besides NAION; (II) a history of orbital, intracranial, or retinal disease that could cause optic nerve damage; (III) presence of neurological or psychiatric symptoms or noncompliance by the patients; and (IV) use of medications that could impact brain function. Five patients and four HCs were excluded due to other kinds of optic nerve disease (n=3), intracranial disease (n=2), or excessive head movement [≥2.5 mm/2.5° or mean framewise displacement (FD) >0.5] (n=4). Ultimately, 25 patients with NAION (57.88±8.73 years; 11 males and 14 females) and 24 HCs (53.46±12.02 years; 9 males and 15 females) matched for age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) without ocular or neurological problems were included. Details of the participant enrollment are provided in Figure 2. Nine of these patients had a second eye involved, and the disease onset was less than 3 months.

In addition, all participants underwent a comprehensive neuro-ophthalmological examination focusing on best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and VF mean deviation (MD), as well as related cognitive assessments using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scale.

MRI data acquisition

All structural and functional data were obtained with a 3-T MRI system (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) equipped with a conventional eight-channel head coil. The rs-fMRI data were collected with an echo planar imaging (EPI) pulse sequence under specific parameters [repetition time (TR) =2,000 ms, echo time (TE) =30 ms, slice number =36, slice thickness =3 mm, gap =1 mm, flip angle (FA) =90°, matrix size =64×64, field of view (FOV) = 240×240 mm2, and time points =200]. T1-weighted images were acquired with a brain volume (BRAVO) sequence under specific settings (TR =8.2 ms, TE =3.2 ms, slice thickness =1 mm, FA =12°, matrix size =256×256, FOV =256×256 mm2, and number of sagittal slices =184). During the rs-fMRI scan, all participants were instructed to keep their heads with the help of foam pads, wear earplugs, keep their eyes open, stay awake, and try to avoid thinking.

Data preprocessing

The preprocessing of functional data was conducted using Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (DPARSF 5.0; http://www.rfmri.org/DPARSF/) based on MATLAB version R2019b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Initial steps involved discarding the first 10 volumes and implementing slice timing and head motion correction. Participants with excessive head motion (more than 2.5-mm translation or 2.5° rotation or FD >0.5) were excluded from further analysis. Subsequently, the corrected fMRI images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space and resampled to a voxel size of 3×3×3 mm3. Linear detrending and bandpass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz) were applied, and several nuisance signals were removed to mitigate non-neuronal fluctuations, including whole-brain head-motion parameters, cerebrospinal fluid signal, and white-matter signal. Spatial smoothing was not performed during data preprocessing due to concerns that it might affect the network structure and attributes (13).

Functional network construction

The identification of network nodes was achieved through the use of the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas, with a focus on 90 cortical and subcortical regions of interest in the brain, excluding the cerebellar areas. After the extraction of the mean time series for each node, the Pearson correlation coefficient was computed between pairs of nodes, resulting in a 90×90 correlation matrix for each individual. Following this, we implemented Fisher Z transformation, leading to the creation of a binary matrix through the application of a predetermined threshold.

Graph theory analyses

The topological properties of functional networks were analyzed using the Graph Theoretical Network Analysis 2.0.0 (GRETNA 2.0.0; http://www.nitrc.org/projects/gretna/) toolbox. We generated a wide range of sparse thresholds from 0.05 to 0.32, with a step size of 0.01 for application to each correlation matrix, in accordance with previous studies (14,15). Several global network parameters were computed and compared across groups, including the normalized clustering coefficient (gamma), normalized characteristic path length (lambda), small-worldness (sigma), global efficiency (Eg), and local efficiency (Eloc). In terms of regional nodal parameters, analyses included nodal degree centrality (Dc), nodal betweenness centrality (Bc), nodal efficiency (Ne), and nodal local efficiency (Nloc). We also calculated another simple but important graph measure, the size of largest connected component (LCC) of the network. To enable unbiased statistical comparisons irrespective of individual threshold choices, the area under the curve (AUC) was determined for each network metric, offering a summary scalar for further analysis.

Network-based statistics (NBS) analysis

To further identify specific alterations in the strength of functional connectivity between patients with NAION and HCs, we employed the NBS method (16). Initially, t scores were calculated for each pairwise connection individually, and the primary threshold (P<0.001) was set to select the connections that exceeded the threshold. Subsequently, we detected the number of connections and their size within the connection component comprising suprathreshold connections. A nonparametric permutation technique was then used to generate to create the empirical null distribution of connection component sizes (5,000 permutations). Finally, the connection component of size M in the actual randomized grouping of patients with NAION and HCs was determined, and the corrected P value was determined according to the proportion of permutations with the largest connection component exceeding M.

Following the extraction of the subnetwork, a correlation analysis was conducted to determine the association between the mean functional connectivity of the subnetwork and the AUC value of the global network properties in both study groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to confirm that the quantitative variables were normally distributed. Differences in demographic information, clinical data, and MoCA scores between patients with NAION and HCs were analyzed using independent two-sample t-tests for variables with a normal distribution and Mann-Whitney tests for those with a nonnormal distribution; meanwhile, differences in gender and risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and OSAS), were assessed with the chi-squared test. Group differences of network metrics in AUC values between two groups were analyzed with two-sample t-tests within GRETNA, with age, sex, and mean FD included as covariates. Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction was applied for multiple comparisons [false-discovery rate (FDR) q<0.05]. In addition, Pearson correlation analyses were performed to investigate the relationship between global network parameters and connectivity metrics in the two groups as well as the correlation between the network topological properties and clinical variables in the NAION group, with age, sex, and mean FD as covariates. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

The demographic and clinical characteristics of all participants are described in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the two groups with respect to age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, OSAS, or MoCA scores. Of note, statistical analysis revealed significantly worse BCVA and increased VF MD in the NAION group (both left and right eyes, P<0.05).

Table 1

| Characteristic | NAION (n=25) | HCs (n=24) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 11/14 | 9/15 | 0.644 |

| Mean age (years) | 57.88±8.73 | 53.46±12.02 | 0.146 |

| Duration (days) | 27.68±16.81 | N/A | N/A |

| Diabetes (Y/N) | 5/20 | 3/21 | 0.746 |

| Systemic hypertension (Y/N) | 7/18 | 5/19 | 0.560 |

| Dyslipidemia (Y/N) | 8/17 | 5/19 | 0.376 |

| Self-reported history of OSA (Y/N) | 1/24 | 0/24 | >0.99 |

| MoCA score | 25.68±2.21 | 26.00±2.55 | 0.641 |

| BCVA-right eye | 0.31±0.52 | 0.03±0.04 | 0.013* |

| BCVA-left eye | 0.64±0.66 | 0.01±0.04 | <0.001* |

| MD of VF-right eye (dB) | 11.81±8.56 | 1.70±2.40 | <0.001* |

| MD of VF-left eye (dB) | 13.57±9.89 | 1.85±1.72 | <0.001* |

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *, statistically significant group differences P<0.05. NAION, nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy; HC, healthy control; M, male; F, female; Y, yes; N, no; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; MD, mean deviation; VF, visual field; N/A, not applicable.

Alterations of global network parameters

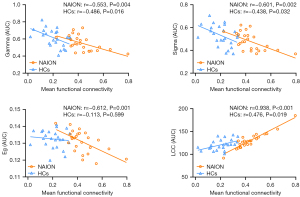

Over the defined threshold level (0.05–0.32), the functional networks of both sets manifested small-world properties (gamma >1, lambda ≈1, and sigma >1). However, compared with HCs, individuals with NAION showed a significant reduction in the AUC values of gamma (P=0.021), sigma (P=0.043), and Eloc (P=0.030) and a marked increase in the AUC values of LCC (P=0.039). Lambda and Eg did not show significant differences between the two groups (Figure 3 and Table S1).

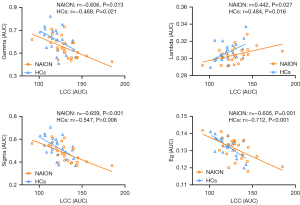

In addition, the correlation of LCC with other global parameters was examined, which demonstrated a negative association between LCC size and gamma (NAION: r=−0.606, P=0.013; HCs: r=−0.468, P=0.021), sigma (NAION: r=−0.659, P<0.001; HCs: r=−0.547, P=0.006), and Eg (NAION: r=−0.605, P=0.001; HCs: r=−0.712, P<0.001) but a positive correlation with lambda (NAION: r=0.442, P=0.027; HCs: r=0.484, P=0.016) in the two groups (Figure 4).

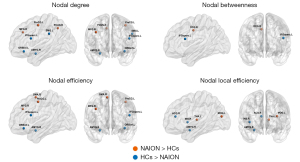

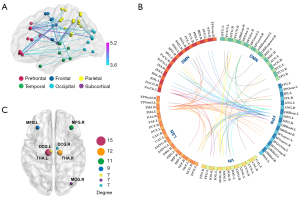

Alterations of regional nodal parameters

Through comparison with the HC group, several brain regions were identified that showed significant between-group differences in at least one nodal measure in the NAION group. Specifically, the NAION group showed increased nodal centralities in the left precentral gyrus (PreCG), right middle frontal gyrus (MFG), right median cingulate and paracingulate gyri (DCG), left middle occipital gyrus (MOG), left precuneus (PCUN), right supplementary motor area (SMA), and left thalamus (THA), most of which are located on the dorsal visual pathway. Conversely, significant reductions in nodal centralities in the NAION group were observed in the left opercular part of the inferior frontal gyrus (IFGoperc), left orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus (ORBinf), right amygdala (AMYG), right insula (INS), left supramarginal gyrus (SMG), and right anterior cingulate and paracingulate gyri (ACG) (Figure 5 and Table S2).

Alterations of brain network connectivity

NBS analysis revealed a significantly increased functional connectivity subnetwork in patients with NAION as compared to HCs, which consisted of 49 nodes and 77 edges (P<0.001, NBS-corrected, T>3.59) (Figure 6A), and no significantly decreased connectivity was observed. Compared to that in HCs, the enhanced functional connectivity in patients with NAION involved multiple brain regions, mainly including the visual network (VN), frontal-parietal network (FPN), and limbic-subcortical network (LSN) (Figure 6B). In order to better characterize the differences in connectivity, we focused on the sum of the edge variances of a node, which allowed us to identify which node links were most likely to be modified by NAION (17,18). The nodes with the largest connection differences predominantly included the bilateral THA, bilateral MFG, bilateral DCG, and right MOG (Figure 6C and Table 2).

Table 2

| Brain region | Anatomical classification | MNI coordinate (x, y, z) | Sum of edge connection |

|---|---|---|---|

| THA.L | Subcortical | (−10.85, −17.56, 7.98) | 15 |

| THA.R | Subcortical | (13.00, −17.55, 8.09) | 12 |

| MFG.R | Prefrontal | (37.59, 33.06, 34.04) | 11 |

| MFG.L | Prefrontal | (−33.43, 32.73, 35.46) | 9 |

| MOG.R | Occipital | (37.39, −79.70, 19.42) | 7 |

| DCG.L | Frontal | (−5.48, −14.92, 41.57) | 7 |

| DCG.R | Frontal | (8.02, −8.83, 39.79) | 7 |

NAION, nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy; HC, healthy control; THA, thalamus; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; DCG, median cingulate and paracingulate gyri; R, right; L, left; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute.

With regard to the global network parameters, the mean functional connectivity of the subnetwork exhibited negative correlations with the AUC of gamma (NAION: r=−0.553, P=0.004; HCs: r=−0.486, P=0.016) and sigma (NAION: r=−0.601, P=0.002; HCs: r=−0.438, P=0.032) and a positive correlation with the AUC of LCC (NAION: r=0.938, P<0.001; HCs: r=0.476, P=0.019) in both the NAION and HC groups; meanwhile, there was a negative correlation with the AUC of Eg in the NAION group (r=−0.612; P=0.001) but not in the HC group (r=−0.113; P=0.599) (Figure 7).

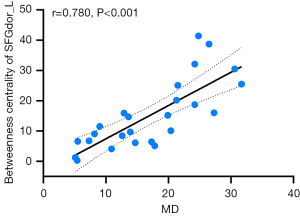

Correlation analysis of clinical parameters

In our analysis for the correlation between the brain network’s topological properties and clinical parameters within the NAION group, we focused on clinical parameters from the affected eye for clarity. For individuals with bilateral onset, we selected the eye with the more severe visual function impairment as the target eye. The findings revealed a significant positive correlation between the nodal betweenness centrality of the left dorsolateral superior frontal gyrus (SFGdor) and VF MD (r=0.780; P<0.001; FDR-corrected) (Figure 8).

Discussion

Functional brain network connections often exhibit small-world properties characterized by high clustering coefficients and short path lengths, which represent a balance between segregation and integration within the network (19,20). In our study, both patients with NAION and healthy individuals displayed efficient small-world properties in their brain networks, but they differed significantly in terms of certain topological metrics and network efficiencies, which is consistent with our previous work (12). The decrease in gamma and sigma among patients with NAION indicates that their brain networks are less modular and error resistant, while lower local efficiencies suggest a decline in local information processing. These alterations imply that the optimal topological organization of the functional network is also disrupted in patients with NAION with concomitant visual impairment. In a sparse network, the LCC is the component containing the highest number of nodes, serving as the network’s core. The growth in the LCC size among patients with NAION suggests fewer disconnected nodes in their network, which is consistent with the enhanced connectivity in their functional networks that was revealed by the NBS analyses. Previous rs-fMRI research has demonstrated that LCC size serves as a crucial predictor for various graphical metrics and may acts as a valuable indicator that could be responsive to the disease state (21). This is consistent with our finding that LCC size was negatively correlated with gamma, sigma, and Eg but positively correlated with lambda.

Regionally, the occipital cortex is a visual perception and processing center, while the MOG is involved in the perception, detection, and extraction of object shape and external visual features and also plays an important role in spatial processing (22-24). The MFG is situated within the parietal-prefrontal pathway of the dorsal visual pathway (25), with its posterior region serving as the site for the frontal eye field (FEF) (26), which is intricately associated with eye movements and selective attention. It can send motor and foveal neurons to the THA and pons in response to visual stimuli, influencing visual activity (27-29). The PreCG, located adjacent to the MFG in the corticomotor center, also contains the FEF. Both the MFG and PreCG are important components of the dorsal attention network (DAN) (30), which is associated with spatial orientation, visuospatial working memory, and the control of visual search (26,31). One study reported increased betweenness centrality in the orbital part of the middle frontal gyrus (ORBmid) and SMA in patients with glaucoma (32). Similarly, the increased nodal centralities in our study may be related to patients’ dysfunction in visually guided movements, attention, and visuospatial abilities, indicating a compensatory boost in occipital-parietal-frontal communication among patients with NAION.

Notably, the IFGoperc and ORBinf exhibited notable decreases in various nodal centralities among patients with NAION. Previous research suggests that the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) is critically involved in audiovisual multisensory integration (33,34), enabling the connection of external information to internal motor evidence through continuous analysis of audiovisual signals (35,36). The tightly connected anterior INS and IFG are part of ventral attention, which together with the AMYG and the ACG compose a salient network (SN) that is often activated synergistically during the performance of cognitively demanding tasks (37,38). In contrast, the reduced nodal centralities in the NAION group also imply that patients have reduced functioning in salience processing and cognitive monitoring.

By applying the NBS method, we identified enhanced subnetwork connectivity in the NAION group involving connections to multiple functional networks such as the VN, FPN, and LSN; among these, the most connected node was the THA, which is an important relay station for incoming and outgoing motor and sensory information in the cerebral cortex and which is tightly connected to various functional networks of the cerebral cortex (39,40). Within the visual system, the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) of the THA acts as the entry point for visual information to reach the cerebral cortex, receiving inputs from RGCs, which then transmit to the primary visual cortex (V1). Patients with NAION often experience damage to RGCs, leading to reduced synaptic inputs to the retina in the THA, subsequently impacting the transfer of functional information between thalamocortical cortices. Huang et al. observed increased functional connectivity in thalamic regions in patients with optic neuritis (41), while Werring et al. reported abnormal activation in several brain areas and the THA when stimulating the recovering eye of such patients (8). These findings constitute evidence for cross-level rewiring of the THA in the absence of retinal input (42,43). In addition to the THA, other highly connected nodes include the bilateral MFG, bilateral DCG, and right MOG, which are similar to the regions of increased node centralities found in the NAION group in our study. These areas of increased network connectivity and nodal regions in patients with NAION suggest a functional reorganization of the brain post-disease, potentially aiding in mitigating the impact of impaired visual function by enhancing the cooperation of functional networks. However, it remains to be seen whether this contributes to functional recovery.

This investigation also examined the correlation between subnetwork functional connectivity and global topological parameters, revealing a negative correlation between average subnetwork functional connectivity and the gamma and sigma in both groups and the Eg in the NAION group. This suggests that individuals with lower average connectivity exhibit higher global metric values, hinting at a potential link between the functional connectivity among brain regions and the overall arrangement of whole-brain functional networks. Furthermore, it indicates that the increased network connectivity in the NAION group did not reflect a boost in network efficiency, but rather an adaptive response.

The superior frontal gyrus, situated in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, plays a role in various functions including eye movement (25,44), complex motor execution (45), and cognitive attention (30,46). Moreover, it is closely connected to the primary visual system through the frontoparietal network (47). Our results demonstrated a significant positive relationship between brain connectivity levels in the left SFGdor and VF MD, implying that spontaneous neural activity in the SFGdor increases with visual dysfunction. This finding is consistent with an fMRI study of glaucoma-related VF damage (48), which found that brain connectivity levels in this area may be valuable in assessing the severity of NAION.

There are several limitations to this study which should be acknowledged. First, this work is a pilot study, and the statistical power is slight due to the small sample size; rather, the aim was to provide valuable data on functional brain network changes in patients with NAION for validation and extension in larger samples with higher statistical power. Second, due to sample size limitations, this study did not stratify between different eye subtypes, and further investigation regarding the effects of different onset eye types on brain networks may provide greater insight. Third, as the study was measurement based on a single point in time, it was not possible to elucidate the progressive changes in functional connectivity of brain networks at different stages of the disease, and prospective longitudinal studies will expand our understanding of this issue. Finally, the examination of correlations between subnetwork FC and global topological parameters is exploratory and data-driven, and the precise mechanism requires clarification through further research.

Conclusions

In this pilot study, complex network analysis based on graph theory was used to investigate the functional connectivity of the brain in patients with NAION. Preliminary results suggest that patients with NAION display disruption of the global properties of functional brain networks and changes in regional nodal centralities as compared to healthy individuals. The subnetwork in patients with NAION exhibited heightened functional connectivity, with a mean connectivity that displayed a negative correlation with the global topological metrics. These findings may indicate that the impact of visual injury on the functional networks of the brain causes reorganization and adaptive changes, the understanding of which may contribute to clarifying the relationship between neurological damage and functional performance in patients with NAION. Nonetheless, studies with larger sample sizes are still needed to elucidate the exact biological mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-2062/rc

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-2062/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Dongfang Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (No. 2017030202). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment in the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Citirak G, Malmqvist L, Hamann S. Analysis of Systemic Risk Factors and Post-Insult Visual Development in a Danish Cohort of Patients with Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Clin Ophthalmol 2022;16:3415-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry S, Lin WV, Sadaka A, Lee AG. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: cause, effect, and management. Eye Brain 2017;9:23-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kerr NM, Chew SS, Danesh-Meyer HV. Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: a review and update. J Clin Neurosci 2009;16:994-1000. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brossard Barbosa N, Donaldson L, Margolin E. Asymptomatic Fellow Eye Involvement in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2023;43:82-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz DM, Trobe JD. Is there treatment for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2015;26:458-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Argyropoulou MI, Zikou AK, Tzovara I, Nikas A, Blekas K, Margariti P, Galatsanos N, Asproudis I. Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: evaluation of the brain and optic pathway by conventional MRI and magnetisation transfer imaging. Eur Radiol 2007;17:1669-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toosy AT, Hickman SJ, Miszkiel KA, Jones SJ, Plant GT, Altmann DR, Barker GJ, Miller DH, Thompson AJ. Adaptive cortical plasticity in higher visual areas after acute optic neuritis. Ann Neurol 2005;57:622-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Werring DJ, Bullmore ET, Toosy AT, Miller DH, Barker GJ, MacManus DG, Brammer MJ, Giampietro VP, Brusa A, Brex PA, Moseley IF, Plant GT, McDonald WI, Thompson AJ. Recovery from optic neuritis is associated with a change in the distribution of cerebral response to visual stimulation: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:441-9.

- Guo P, Zhao P, Lv H, Su Y, Liu M, Chen Y, Wang Y, Hua H, Kang S. Abnormal Regional Spontaneous Neural Activity in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Resting-State Functional MRI Study. Neural Plast 2020;2020:8826787. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao P, Lv H, Guo P, Su Y, Liu M, Wang Y, Hua H, Kang S. Altered Brain Functional Connectivity at Resting-State in Patients With Non-arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Front Neurosci 2021;15:712256. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mears D, Pollard HB. Network science and the human brain: Using graph theory to understand the brain and one of its hubs, the amygdala, in health and disease. J Neurosci Res 2016;94:590-605. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Yan X, Zhang Q, Wu Q, Qiu L, Zhou J, Guo P. Altered small-world and disrupted topological properties of functional connectivity networks in patients with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2024;236:108101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alakörkkö T, Saarimäki H, Glerean E, Saramäki J, Korhonen O. Effects of spatial smoothing on functional brain networks. Eur J Neurosci 2017;46:2471-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Wang J, Wu Q, Kuang W, Huang X, He Y, Gong Q. Disrupted brain connectivity networks in drug-naive, first-episode major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2011;70:334-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yong W, Song J, Xing C, Xu JJ, Xue Y, Yin X, Wu Y, Chen YC. Disrupted Topological Organization of Resting-State Functional Brain Networks in Age-Related Hearing Loss. Front Aging Neurosci 2022;14:907070. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Xia Y, Yan R, Wang H, Sun H, Huang Y, Hua L, Tang H, Yao Z, Lu Q. The relationship between disrupted anhedonia-related circuitry and suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder: A network-based analysis. Neuroimage Clin 2023;40:103512. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finn ES, Shen X, Holahan JM, Scheinost D, Lacadie C, Papademetris X, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA, Constable RT. Disruption of functional networks in dyslexia: a whole-brain, data-driven analysis of connectivity. Biol Psychiatry 2014;76:397-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan X, Wu Y, Cai L, Ma J, Pan N, Xu X, Sun T, Jing J, Li X. The Differences in the Whole-Brain Functional Network between Cantonese-Mandarin Bilinguals and Mandarin Monolinguals. Brain Sci 2021;11:310. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu H, Zheng H, Zhang G, Zhuang J, Li W, Wu B, Zheng W. A Graph Theory Study of Resting-State Functional MRI Connectivity in Children With Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. J Magn Reson Imaging 2023;58:1452-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao Y, Zhan Y, Du M, Zhao G, Liu Z, Zhou F, He L. Disruption of human brain connectivity networks in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021;11:3418-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bassett DS, Nelson BG, Mueller BA, Camchong J, Lim KO. Altered resting state complexity in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 2012;59:2196-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei L, Li X, Huang L, Liu Y, Hu L, Shen W, Ding Q, Liang P. An fMRI study of visual geometric shapes processing. Front Neurosci 2023;17:1087488. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tu S, Qiu J, Martens U, Zhang Q. Category-selective attention modulates unconscious processes in the middle occipital gyrus. Conscious Cogn 2013;22:479-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renier LA, Anurova I, De Volder AG, Carlson S, VanMeter J, Rauschecker JP. Preserved functional specialization for spatial processing in the middle occipital gyrus of the early blind. Neuron 2010;68:138-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kravitz DJ, Saleem KS, Baker CI, Mishkin M. A new neural framework for visuospatial processing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011;12:217-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petit L, Pouget P. The comparative anatomy of frontal eye fields in primates. Cortex 2019;118:51-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Helminski JO, Segraves MA. Macaque frontal eye field input to saccade-related neurons in the superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 2003;90:1046-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bedini M, Baldauf D. Structure, function and connectivity fingerprints of the frontal eye field versus the inferior frontal junction: A comprehensive comparison. Eur J Neurosci 2021;54:5462-506. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor PC, Nobre AC, Rushworth MF. FEF TMS affects visual cortical activity. Cereb Cortex 2007;17:391-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox MD, Corbetta M, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Raichle ME. Spontaneous neuronal activity distinguishes human dorsal and ventral attention systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:10046-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois A, Sterpenich V, Iannotti GR, Vuilleumier P. Reward-driven modulation of spatial attention in the human frontal eye-field. Neuroimage 2022;247:118846. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Li T, Wang N, Xian J, He H. Graph theoretical analysis reveals the reorganization of the brain network pattern in primary open angle glaucoma patients. Eur Radiol 2016;26:3957-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morís Fernández L, Macaluso E, Soto-Faraco S. Audiovisual integration as conflict resolution: The conflict of the McGurk illusion. Hum Brain Mapp 2017;38:5691-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Seger C, Chen Q, Mo L. Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus Integrates Multisensory Information in Category Learning. Cereb Cortex 2020;30:4410-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papadelis C, Arfeller C, Erla S, Nollo G, Cattaneo L, Braun C. Inferior frontal gyrus links visual and motor cortices during a visuomotor precision grip force task. Brain Res 2016;1650:252-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Binkofski F, Buccino G. The role of ventral premotor cortex in action execution and action understanding. J Physiol Paris 2006;99:396-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elton A, Gao W. Divergent task-dependent functional connectivity of executive control and salience networks. Cortex 2014;51:56-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:12569-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hwang K, Bertolero MA, Liu WB, D'Esposito M. The Human Thalamus Is an Integrative Hub for Functional Brain Networks. J Neurosci 2017;37:5594-607. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bell PT, Shine JM. Subcortical contributions to large-scale network communication. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;71:313-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Duan Y, Liu S, Liang P, Ren Z, Gao Y, Liu Y, Zhang X, Lu J, Li K. Altered Brain Structure and Functional Connectivity of Primary Visual Cortex in Optic Neuritis. Front Hum Neurosci 2018;12:473. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qin Y, Ahmadlou M, Suhai S, Neering P, de Kraker L, Heimel JA, Levelt CN. Thalamic regulation of ocular dominance plasticity in adult visual cortex. Elife 2023;

- Grant E, Hoerder-Suabedissen A, Molnár Z. The Regulation of Corticofugal Fiber Targeting by Retinal Inputs. Cereb Cortex 2016;26:1336-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi W, Desai RH, Henderson JM. The neural substrates of natural reading: a comparison of normal and nonword text using eyetracking and fMRI. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;8:1024. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martino J, Gabarrós A, Deus J, Juncadella M, Acebes JJ, Torres A, Pujol J. Intrasurgical mapping of complex motor function in the superior frontal gyrus. Neuroscience 2011;179:131-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michalka SW, Kong L, Rosen ML, Shinn-Cunningham BG, Somers DC. Short-Term Memory for Space and Time Flexibly Recruit Complementary Sensory-Biased Frontal Lobe Attention Networks. Neuron 2015;87:882-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Griffis JC, Elkhetali AS, Burge WK, Chen RH, Bowman AD, Szaflarski JP, Visscher KM. Retinotopic patterns of functional connectivity between V1 and large-scale brain networks during resting fixation. Neuroimage 2017;146:1071-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang R, Tang Z, Liu T, Sun X, Wu L, Xiao Z. Altered spontaneous neuronal activity and functional connectivity pattern in primary angle-closure glaucoma: a resting-state fMRI study. Neurol Sci 2021;42:243-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]