Evaluation of silicosis combined with type 2 diabetes mellitus based on the quantitative CT measured parameters

Introduction

Pneumoconiosis is a type of occupational lung disease caused by long-term dust exposure (1), and this condition has led to an approximate 0.4% decline in the gross national product of China (2). Silicosis, the primary form of pneumoconiosis, is the most serious and common occupational disease in China and accounts for 88.3% of all reported cases of pneumoconiosis (3). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is increasing globally every year (4). In similarity with silicosis, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus imposes an enormous burden on society, resulting in high medical costs for patients and their families and adverse health consequences for the affected individuals (5).

On the one hand, both T2DM and silicosis can cause heart damage, and it is thought that T2DM can directly affect both the structure and function of the myocardium, a condition referred to as diabetic cardiomyopathy (6,7). On the other hand, pneumoconiosis can lead to chronic pulmonary heart disease due to its association with emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis (8). However, the alterations in the heart structure of patients with silicosis combined with diabetes mellitus remain poorly understood.

Computed tomography (CT)-measured cardiac and lung parameters have been used in patients with cardiopulmonary diseases such as pulmonary embolic disease (9), emphysema (10), and left ventricular enlargement (11). CT-measured cardiac parameters can reveal changes in cardiac structure even in non-contrast images (12) and have been shown to be related to prognosis in some cardiopulmonary diseases (13).

To our knowledge, there has been no prior research examining whether concurrent diabetes mellitus impacts cardiopulmonary structures and lung function in patients with silicosis. We posit that comorbid diabetes may affect cardiopulmonary structures and lung function in these patients. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to evaluate the differences in cardiopulmonary structural changes between silicosis patients with diabetes mellitus (SCD group) and those without diabetes mellitus (SWD group) on the basis of CT parameters and to investigate the factors influencing lung function. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1748/rc).

Methods

Recruitment of patients and controls

This was a retrospective study for which approval from the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Hospital of West China, Sichuan University was obtained (No. HXSY-EC-2022096). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for individual patient consent was waived. Patients diagnosed with silicosis, staged according to a history of silica dust exposure per the China National Diagnostic Criteria for Pneumoconiosis (GBZ-2015) (14), which aligns with the International Labor Organization Classification of Pneumoconiosis (15), were included in the study between 1 January 2012 and 31 May 2024. The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was made by an endocrinologist on the basis of the patient’s blood test results. The collected data included demographic information, details of dust exposure history, chest CT images, pulmonary function test (PFT) results, and hematological results. The exclusion criteria encompassed patients with biopsy-confirmed tuberculosis as well as those diagnosed with tuberculosis based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

The CT protocols

In this study, CT scans were conducted with a 16-channel CT scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and a 256-channel CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Patients were placed in the supine position with their arms elevated above their heads, and scans proceeded from the apex to the base of the lungs during end-inspiratory breath-holding. Standard radiation protection measures (16) were employed throughout the scanning process to minimize the exposure of patients and staff to ionizing radiation. The non-contrast CT chest parameters for the CT scans included a tube voltage set between 120 and 130 kVp, a tube current ranging from 110 to 300 mAs, a pitch of 0.992–1.2, an image matrix configured at 512×512, and a reconstructed slice thickness of 1.5 mm.

The CT-measured parameters

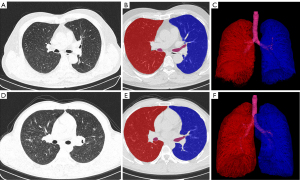

Three-dimensional (3D) volume and mass measurements of all the CT images were automatically calculated on high-resolution displays with an image archiving and communication system provided by CREALIFE Technology, Inc. (Beijing, China) (17). The lung parameters derived from the CT measurements included total lung volume (TLV) and total lung mass (TLM) (Figure 1).

The acquired image datasets were transferred to a dedicated reprocessing workstation (CREALIFE Technology) where they were processed via volume rendering and curved planar reconstruction methods. This retrospective analysis was carried out by two radiologists employing a double-blinded methodology, and the outcomes were averaged for accuracy.

Measurements of the cardiac parameters via CT were based on methodologies suggested by Guo et al. (9), in which specific measurement tools were utilized. The cardiac parameters measured from CT imaging are detailed as follows (Figure 2): longest diameter from left to right of the left atrium (LALR), longest diameter from left to right of the left ventricle (LVLR), longest diameter from left to right of the right atrium (RALR), longest diameter from left to right of the right ventricle (RVLR), longest anteroposterior diameter of the left atrium (LAAP), longest anteroposterior diameter of the left ventricle (LVAP), longest anteroposterior diameter of the right atrium (RAAP), and longest anteroposterior diameter of the right ventricle (RVAP).

PFTs

PFTs were conducted in strict adherence to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) guidelines (18) and were administered by specialists within the Pulmonary Function Department of the Fourth Hospital of West China, Sichuan University. These tests utilized a state-of-the-art clinical spirometer (MasterScreen PFT, Jaeger; Vyaire Medical, Höchberg, Germany) for accurate measurement. Relevant lung function metrics were retrieved from patients’ medical records. The recorded lung function parameters included forced vital capacity (FVC), the ratio of FEV1/FVC, maximum vital capacity (VC MAX), residual volume (RV), total lung capacity (TLC), and the diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO).

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were executed with the software SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Continuous variables were summarized as the means ± standard deviations, whereas categorical variables were represented by counts (n) and percentages (%). Paired t-tests were applied for comparisons involving continuous variables, and chi-square tests were utilized for those involving categorical variables. To assess the relationships between CT-measured parameters and pulmonary function, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted. Linear regression analysis was employed to identify the determinants of lung function impairment in the SCD group.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The study comprised two cohorts: the SCD group (n=30) and the comparably matched SWD group (n=30), with both groups consisting solely of male participants. Both cohorts were diagnosed by the Occupational Disease Evaluation Panel and confirmed by endocrinology specialists. No significant differences were observed between the groups regarding age, silicosis stage, smoking history, or duration of dust exposure, with all P values >0.05. Notably, the SCD group had a significantly higher body mass index (BMI) than did the SWD group (P<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variables | SWD group (n=30) | SCD group (n=30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicosis stage | >0.99 | ||

| Stage I | 12 (40.0) | 12 (40.0) | |

| Stage II | 9 (30.0) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Stage III | 9 (30.0) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Age (years) | 51.87±12.07 | 55.80±10.41 | 0.222 |

| Smoking | 0.754 | ||

| Yes | 23 (76.7) | 24 (80.0) | |

| No | 7 (23.3) | 6 (20.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.07±3.03 | 26.59±2.99 | <0.001* |

| Years of dust exposure (yeas) | 10.62±7.07 | 9.29±5.05 | 0.253 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD. *, P<0.05. SWD, silicosis without diabetes mellitus; SCD, silicosis combined with diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Differences in the hematology results, CT-measured parameters, and pulmonary function results in the SCD versus SWD group

The comparative analysis of quantitative CT lung and cardiac parameters revealed that the TLM values in the SCD group were significantly lower than those in the SWD group (P=0.048). Furthermore, the SCD group showed significantly higher values for LVLR (70.53±6.29 mm) compared to the SWD group, which had a corresponding value of 65.60±10.35 mm (P=0.030). However, in the comparisons of the SCD and SWD groups, there was no significant difference in TLV, LAAP, LALR, LVAP, RVAP, RVLR, RAAP, or RALR (all P>0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variables | SWD group (n=30) | SCD group (n=30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLV (mL) | 4,729.63±1,192.60 | 4,502.59±685.35 | 0.399 |

| TLM (g) | 1,029.40±177.55 | 959.21±120.84 | 0.048* |

| LAAP (mm) | 30.00±6.41 | 33.01±6.20 | 0.101 |

| LALR (mm) | 65.27±9.48 | 64.01±8.12 | 0.557 |

| LVAP (mm) | 48.92±6.25 | 50.45±5.37 | 0.342 |

| LVLR (mm) | 65.60±10.35 | 70.53±6.29 | 0.030* |

| RVAP (mm) | 48.84±26.80 | 45.82±7.49 | 0.521 |

| RVLR (mm) | 55.52±8.86 | 58.60±4.91 | 0.109 |

| RAAP (mm) | 40.09±7.74 | 40.30±5.84 | 0.904 |

| RALR (mm) | 43.35±8.29 | 41.48±7.32 | 0.308 |

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *, P<0.05. CT, computed tomography; SWD, silicosis without diabetes mellitus; SCD, silicosis combined with diabetes mellitus; TLV, the total lung volume; TLM, total lung mass; LAAP, anteroposterior diameters of the left atrium; LALR, the longest diameters from left to right of the left atrium; LVAP, anteroposterior diameters of the left ventricle; RVAP, anteroposterior diameters of the right ventricle; RVLR, longest diameters from left to right of the right ventricle; LVLR, the longest diameters from left to right of the left ventricle; RAAP, anteroposterior diameters of the right atrium; RALR, longest diameters from left to right of the right atrium.

The SCD group showed significantly higher values for blood glucose and triglycerides compared to the SWD group (all P<0.05). Additionally, there were no significant differences between the SCD and SWD groups in other hematological indices such as total protein (TP) and albumin (ALB) (all P>0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variables | SWD group (n=30) | SCD group (n=30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP (g/L) | 66.40±6.59 | 67.37±5.11 | 0.589 |

| ALB (g/L) | 39.86±3.64 | 40.36±3.99 | 0.645 |

| GLB (g/L) | 26.53±4.74 | 27.02±3.07 | 0.641 |

| ALT (U/L) | 34.00±36.91 | 32.67±22.53 | 0.865 |

| AST (U/L) | 31.37±31.53 | 24.43±11.69 | 0.268 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 17.67±10.60 | 16.73±4.26 | 0.635 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 4.81±2.84 | 5.16±1.81 | 0.573 |

| IBIL (μmol/L) | 12.88±8.79 | 11.57±3.68 | 0.418 |

| ALP (U/L) | 68.83±25.37 | 70.60±21.77 | 0.760 |

| GGT (U/L) | 38.77±56.47 | 39.10±23.96 | 0.976 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.21±1.48 | 5.12±1.70 | 0.848 |

| CREA (μmol/L) | 74.67±11.78 | 74.18±16.40 | 0.884 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 343.03±102.68 | 429.30±452.36 | 0.913 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 5.31±0.65 | 8.10±2.99 | <0.001* |

| CHOL (mmol/L) | 4.68±0.91 | 4.80±1.05 | 0.640 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.19±0.53 | 1.89±0.84 | 0.001* |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.33±0.40 | 1.16±0.28 | 0.092 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.12±0.84 | 3.12±0.84 | 0.495 |

| K (mmol/L) | 4.05±0.43 | 3.96±0.28 | 0.322 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 138.80±2.27 | 139.33±2.20 | 0.388 |

| Cl (mmol/L) | 105.31±3.54 | 105.78±4.02 | 0.624 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 2.28±0.12 | 2.33±0.13 | 0.102 |

| P (mmol/L) | 1.09±0.21 | 1.09±0.15 | 0.967 |

| Mg (mmol/L) | 0.83±0.07 | 0.79±0.08 | 0.134 |

| Fe (μmol/L) | 16.7±5.38 | 16.11±7.53 | 0.700 |

| CO2CP (mmol/L) | 24.03±2.92 | 23.33±3.72 | 0.449 |

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *, P<0.05. SWD, silicosis without diabetes mellitus; SCD, silicosis combined with diabetes mellitus; TP, total protein; ALB, albumin; GLB, globulin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST aspartate transaminase; TBIL, total bilirubin; DBIL, direct bilirubin; IBIL, indirect bilirubin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CREA, creatinine; UA, uric acid; GLU, glucose; CHOL, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; K, potassium; Na, sodium; Cl, chlorine; Ca, calcium; P, phosphorus; Mg, magnesium; Fe, iron; CO2CP, carbon-dioxide combining power.

In the comparisons of lung function, the SCD group had a significantly lower FEV1/FVC (78.69%±10.96%) than did the SWD group (89.31%±7.41%, P<0.001). There were no significant differences in FVC, VC MAX, RV, TLC, or DLCO between the SCD and SWD groups (all P>0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Variables | SWD group (n=30) | SCD group (n=30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FVC (L) | 2.54±0.98 | 2.67±0.93 | 0.616 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 89.31±7.41 | 78.69±10.96 | <0.001* |

| VC MAX (L) | 2.66±0.99 | 2.79±0.88 | 0.594 |

| RV (L) | 2.64±0.80 | 2.86±0.93 | 0.328 |

| TLC (L) | 5.33±1.22 | 5.71±0.87 | 0.201 |

| DLCO (mmol/min/kPa) | 6.29±2.75 | 5.64±2.02 | 0.311 |

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *, P<0.05. SWD, silicosis without diabetes mellitus; SCD, silicosis combined with diabetes mellitus; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1/FVC, ratio of FEV1 to FVC; VC MAX, maximum vital capacity; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung volume; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide.

Analysis of correlations between pulmonary function and CT-measured parameters in the SCD group

FEV1/FVC exhibited significant correlations with TLM, LALR, LVLR, and RALR, with correlation coefficients (r) of 0.51, 0.47, 0.40, and 0.44, respectively (all P<0.05) (Figure 3).

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses of the SCD group

The univariate linear regression analysis for the SCD group revealed that silicosis stage, age, TLM, LALR, LVLR, and RALR were factors affecting FEV1/FVC, with all P values less than 0.05. Based on the results of univariate linear regression and previous studies (19-21), silicosis stage, age, smoking history, BMI, TLM, LALR, LVLR, RALR, and laboratory test results (including blood glucose, calcium, phosphorus, and iron levels) were included in the multivariate linear regression analysis. This analysis indicated that BMI and LVLR were independent determinants of FEV1/FVC (β coefficients of −0.506 and 0.317, respectively, with respective P values of 0.002 and 0.049) (Table 5).

Table 5

| Variables | Estimate | Standard error | t value | P value | 95% confidence interval | Collinearity statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Tolerance | Variance inflation factor |

||||||

| Multiple regression analysis for FEV1/FVC of subjects with complete data (n=30) | |||||||||

| Age (years old) | −0.133 | 0.155 | −0.856 | 0.404 | −0.461 | 0.195 | 0.564 | 1.774 | |

| Silicosis stage | −3.221 | 2.011 | −1.602 | 0.128 | −7.463 | 1.022 | 0.511 | 1.956 | |

| BMI | −1.798 | 0.534 | −3.367 | 0.004* | −2.924 | −0.671 | 0.580 | 1.724 | |

| Smoking | 7.350 | 3.857 | 1.906 | 0.074 | −0.787 | 15.486 | 0.599 | 1.668 | |

| TLM | 0.005 | 0.002 | 2.075 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.530 | 1.885 | |

| LALR | 0.246 | 0.249 | 0.986 | 0.338 | −0.280 | 0.771 | 0.361 | 2.772 | |

| LVLR | 0.670 | 0.271 | 2.471 | 0.024* | 0.098 | 1.243 | 0.508 | 1.970 | |

| RALR | 0.378 | 0.300 | 1.263 | 0.224 | −0.254 | 1.011 | 0.307 | 3.260 | |

| GLU | 0.572 | 0.477 | 1.198 | 0.247 | −0.435 | 1.578 | 0.726 | 1.377 | |

| Ca | 15.134 | 12.200 | 1.240 | 0.232 | −10.606 | 40.874 | 0.626 | 1.598 | |

| P | 8.983 | 12.435 | 0.722 | 0.480 | −17.252 | 35.218 | 0.422 | 2.371 | |

| Fe | 0.272 | 0.228 | 1.192 | 0.249 | −0.209 | 0.754 | 0.499 | 2.002 | |

*, P<0.05. BMI, body mass index; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity ratio; SCD, silicosis combined with diabetes mellitus; TLM, total lung mass; LALR, the longest diameters from left to right of the left atrium; LVLR, the longest diameters from left to right of the left ventricle; RALR, the longest diameters from left to right of the right atrium; GLU, glucose; Ca, calcium; P, phosphorus; Fe, iron.

Discussion

The study findings showed that the SCD cohort manifested an enlarged LVLR alongside suboptimal pulmonary function indicators, such as a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio. This observation implies a probable direct reciprocity between cardiac morphology and pulmonary health, indicating mutual influence. The correlation identified between the SCD cohort’s FEV1/FVC and parameters quantified by CT underscores the importance of imaging methods in evaluating respiratory system disorders. A single thoracic CT scan not only provides structural metrics but also offers predictive insights into FEV1/FVC, potentially enhancing the precision of disease diagnosis and monitoring its progression. This insight provides a novel perspective for the exploration of SCD. Furthermore, BMI and LVLR have been validated as independent determinants of pulmonary function in the SCD patient population. This might steer targeted intervention strategies for specific risk factors in clinical practice.

CT-measured lung parameters serve as dependable indices for assessing lung pathology, encompassing conditions such as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (22) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (23), with CT-derived lung masses demonstrating strong concordance with in vivo lung masses (24). Our investigation revealed a reduction in TLM and the FEV1/FVC ratio in the SCD cohort compared with those in the SWD cohort, diverging slightly from previous findings. Prior research has indicated an increase in FEV1/FVC among patients with T2DM relative to healthy controls (19); conversely, our data show a decline in FEV1/FVC within the SCD cohort vis-à-vis the SWD cohort. This discrepancy might be attributable to our focus on a population with preexisting silicosis, where the co-occurrence of T2DM potentially exacerbates the pulmonary impact of silicosis. Historically, studies have reported a decrease in lung mass among individuals with COPD, with a trend toward decreasing lung mass as COPD severity increases (23), whereas emphysema is associated with an increase in lung mass (10). Patients with pneumoconiosis are predisposed to concurrent COPD (25), which may explain the reduced lung mass observed in the SCD cohort relative to the SWD cohort in our study.

Pulmonary dysfunction in diabetic patients predominantly involves four pivotal mechanisms: non-enzymatic glycation of lung collagen and elastin by advanced glycation end products, leading to diminished lung elasticity; thickening of the alveolar epithelial basement membrane and alterations in the microvasculature, reducing alveolar capillary blood volume and diffusion capacity; autonomic neuropathy impacting the phrenic nerve, causing decreased muscle tone and impaired diaphragmatic control; and hyperglycemia increasing the glucose concentration in airway surface liquid, fostering bacterial colonization, increasing the frequency of acute exacerbations akin to those of COPD, and worsening post-intervention treatment outcomes (19,26). All these pathways may synergize with other lung diseases, such as silicosis in our study, potentially leading to adverse consequences in patients concurrently afflicted by both conditions.

We hypothesize that in SCD patients, impaired diaphragmatic control due to phrenic nerve involvement and increased glucose content in airway surface liquid may contribute to a decrease in FEV1/FVC, favoring an obstructive phenotype.

Diabetic cardiomyopathy primarily affects the left heart (27). Cosyns et al. (28) and Yu et al. (29) reported that diabetic patients had a larger left ventricle (LV) diameter than control patients did. Gimenes et al. (30) and Markus et al. (31) found that diabetic rats had larger LV and left atrium (LA) diameters than control rats did. Zhou et al. (32) found that the LAAP in the diabetic rabbit group was larger than that in the control group. This study revealed that T2DM increased the LVLR in silicosis patients, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. However, Jørgensen et al. (33) and Li et al. (34) reported that the diabetic group had a lower LV diameter than the control group did. The reason may be that diabetic cardiomyopathy is “two-faced” according to Seferović’s study. Seferović argued that diabetic cardiomyopathy presented as either dilated cardiomyopathy or restrictive cardiomyopathy (35). Our study revealed that SCD patients exhibit a dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype.

Our study demonstrated that, within the SCD cohort, BMI and LVLR serve as independent determinants of pulmonary function, highlighting the complexity of lung function decline. An elevated BMI, indicative of increased abdominal and thoracic adiposity, exerts mechanical pressure on the diaphragm, restricting lung expansion and diminishing the lung volume. In combination with inflammatory processes and oxidative stress, this exacerbates pulmonary injury (20,21,36). An augmented LVLR signifies left ventricular dysfunction, compromising cardiac output and elevating pulmonary circulation pressure, thus hindering effective gas exchange (37,38). Overall, obesity augments cardiac workload, impairs left ventricular integrity, and engenders a vicious cycle that further deteriorates pulmonary function. Against the backdrop of silicosis, these factors intensify the deterioration of lung function. Consequently, patients with silicosis require vigilant weight and cardiovascular health management, necessitating a comprehensive intervention approach to optimize prognosis.

Our findings revealed that in the SCD cohort, the FEV1/FVC ratios correlated moderately with TLM, LALR, LVLR, and RALR, diverging from prior studies on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adolescents, where the lung mass and volume were moderately positively correlated with FEV1 but not with FEV1/FVC (39). This disparity could stem from differing age profiles and environmental exposures. Diabetes and silicosis in tandem might create unique cardiac-pulmonary interdependencies not observed in HIV-infected youth, as diabetes-induced cardiac alterations and silicosis-related lung fibrosis could synergistically affect the FEV1/FVC ratio (19,28,40). HIV-related lung dysfunction likely stems from viral lung injury rather than from cardiac factors. Remarkably, our data suggest that CT scans can be used to partially quantify lung function impairment in SCD patients, suggesting a potential alternative to PFTs.

There have been no previous studies on the impact of diabetes on cardiopulmonary structure and lung function. Our study contrasts the SCD and SWD groups, showing higher BMI, glucose, TG, and LVLR in the SCD group, alongside reduced lung mass and FEV1/FVC. We found a significant correlation between the FEV1/FVC and CT-obtained lung parameters of SCD patients, highlighting the link between lung function and structural changes. Importantly, BMI and LVLR were confirmed to be independent factors affecting SCD patients’ lung function, indicating that metabolic health and cardiac structure play critical roles in pulmonary health. These findings enhance the understanding of the effects of systemic disease on lung function and guide health management in SCD cases; it also provides future directions for research on metabolic-cardio-respiratory disease interconnections.

Previous studies have shown that smoking increases the risk to the cardiovascular system and damages lung function (41). In our study, although there was no difference in smoking prevalence between the SCD and SWD groups, and smoking was not identified as a significant factor affecting lung function in multivariate analysis, this may have been due to the relatively small sample size. Future research with larger sample sizes should further investigate the relationship between smoking and the comorbidity of silicosis and diabetes mellitus. Although pulmonary tuberculosis has been excluded in this study, patients with silicosis and diabetes mellitus are prone to coexisting tuberculosis (42), which may affect cardio-pulmonary structure and lung function. This issue will be further explored in future studies.

We acknowledge that this study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center, cross-sectional study with a small sample size, which may have introduced some selection bias. Additionally, although the study continuously recruited silicosis patients, the participants were predominantly male. We hope that future multicenter studies will include a larger number of female patients with silicosis. Lastly, the use of different CT scanners could introduce minor measurement biases; in future studies, we will use the same model of scanner to improve consistency.

Conclusions

Diabetes amplifies lung function decline in silicosis patients, with BMI and LVLR as key independent factors. Enhanced personalized management, focusing on weight and cardiac health, is crucial for these patients to mitigate lung function deterioration and enhance quality of life. This study deepens the understanding of SCD health profiles, offering valuable insights for future research and clinical strategies against the dual threat of diabetes and silicosis.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1748/rc

Funding: This research was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1748/coif). All authors report the funding from the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (No. 2023NSFSC1713). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Hospital of West China, Sichuan University (No. HXSY-EC-2022096), and the requirement for individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bian LQ, Mao L, Bi Y, Zhou SW, Chen ZD, Wen J, Shi J, Wang L. Loss of regulatory characteristics in CD4(+) CD25(+/hi) T cells induced by impaired transforming growth factor beta secretion in pneumoconiosis. APMIS 2017;125:1108-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang YX, Wong O, Fu H, Hu TX, Xue SZ. The economic burden of pneumoconiosis in China. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:383-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia Y, Liu J, Shi T, Xiang H, Bi Y. Prevalence of pneumoconiosis in Hubei, China from 2008 to 2013. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:8612-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:137-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, Malanda B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;138:271-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited. Circulation 2007;115:3213-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fang ZY, Prins JB, Marwick TH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev 2004;25:543-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi D, Zhang J, Liu X, Zhang G, Cui L. Evaluation of the right ventricular function in pneumoconiosis patients using volume-time curves obtained by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. Cell Biochem Biophys 2014;70:1553-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo ZJ, Liu HT, Bai ZM, Lin Q, Zhao BH, Xu Q, Zeng YH, Feng WQ, Zhou HT, Liang F, Cui JY. A new method of CT for the cardiac measurement: correlation of computed tomography measured cardiac parameters and pulmonary obstruction index to assess cardiac morphological changes in acute pulmonary embolism patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2018;45:410-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guenard H, Diallo MH, Laurent F, Vergeret J. Lung density and lung mass in emphysema. Chest 1992;102:198-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torres FS, Folador L, Eifer DA, Foppa M, Hanneman K. Measuring Left Ventricular Size in Non-Electrocardiographic-gated Chest Computed Tomography: What Radiologists Should Know. J Thorac Imaging 2018;33:81-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeon SB, Salton CJ, Gona P, Chuang ML, Blease SJ, Han Y, Tsao CW, Danias PG, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, Manning WJ. Impact of age, sex, and indexation method on MR left ventricular reference values in the Framingham Heart Study offspring cohort. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41:1038-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyer G, Sanchez O, Jimenez D. Risk assessment and management of high and intermediate risk pulmonary embolism. Presse Med 2015;44:e401-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. Diagnosis of occupational pneumoconiosis. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/, accessed 15, December 2015.

- International Labour Organization. Guidelines for the use of the ILO International Classification of Radiographs of Pneumoconioses. Revised edition 2022 ed. Geneva: 2022.

- China NHCotPsRo. Diagnostic Radiation Protection Requirements. 2020. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/, accessed 2020-04-03 2020.

- crealife. CT Pulmonary Analysis. 2024. Available online: https://www.crealifemed.com/

- Wu WH, Feng YH, Min CY, Zhou SW, Chen ZD, Huang LM, Yang WL, Yang GH, Li J, Shi J, Quan H, Mao L. Clinical efficacy of tetrandrine in artificial stone-associated silicosis: A retrospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023;10:1107967. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kinney GL, Black-Shinn JL, Wan ES, Make B, Regan E, Lutz S, Soler X, Silverman EK, Crapo J, Hokanson JE. COPDGene Investigators. Pulmonary function reduction in diabetes with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Diabetes Care 2014;37:389-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reay WR, El Shair SI, Geaghan MP, Riveros C, Holliday EG, McEvoy MA, Hancock S, Peel R, Scott RJ, Attia JR, Cairns MJ. Genetic association and causal inference converge on hyperglycaemia as a modifiable factor to improve lung function. Elife 2021;10:e63115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang RH, Zhou JB, Cai YH, Shu LP, Simó R, Lecube A. Non-linear association between diabetes mellitus and pulmonary function: a population-based study. Respir Res 2020;21:292. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feng X, Ding X, Zhang F. Dynamic evolution of lung abnormalities evaluated by quantitative CT techniques in patients with COVID-19 infection. Epidemiol Infect 2020;148:e136. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Washko GR, Kinney GL, Ross JC, San José Estépar R, Han MK, Dransfield MT, Kim V, Hatabu H, Come CE, Bowler RP, Silverman EK, Crapo J, Lynch DA, Hokanson J, Diaz AA. COPDGene Investigators. Lung Mass in Smokers. Acad Radiol 2017;24:386-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henne E, Anderson JC, Lowe N, Kesten S. Comparison of human lung tissue mass measurements from ex vivo lungs and high resolution CT software analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2012;12:18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Acun Pinar M, Sari G, Koyuncu A, Şimşek C. Factors Affecting Development of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Pneumoconiosis Cases: A Cross-sectional Study Between 2017 and 2022 in Turkey. J Occup Environ Med 2023;65:694-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mittal S, Jindal M, Srivastava S, Sinha S. Evaluation of Pulmonary Functions in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023;15:e35628. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ritchie RH, Abel ED. Basic Mechanisms of Diabetic Heart Disease. Circ Res 2020;126:1501-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cosyns B, Droogmans S, Hernot S, Degaillier C, Garbar C, Weytjens C, Roosens B, Schoors D, Lahoutte T, Franken PR, Van Camp G. Effect of streptozotocin-induced diabetes on myocardial blood flow reserve assessed by myocardial contrast echocardiography in rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2008;7:26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu X, Tesiram YA, Towner RA, Abbott A, Patterson E, Huang S, Garrett MW, Chandrasekaran S, Matsuzaki S, Szweda LI, Gordon BE, Kem DC. Early myocardial dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice: a study using in vivo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Cardiovasc Diabetol 2007;6:6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gimenes R, Gimenes C, Rosa CM, Xavier NP, Campos DHS, Fernandes AAH, Cezar MDM, Guirado GN, Pagan LU, Chaer ID, Fernandes DC, Laurindo FR, Cicogna AC, Okoshi MP, Okoshi K. Influence of apocynin on cardiac remodeling in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018;17:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Markus MR, Stritzke J, Wellmann J, Duderstadt S, Siewert U, Lieb W, Luchner A, Döring A, Keil U, Schunkert H, Hense HW. Implications of prevalent and incident diabetes mellitus on left ventricular geometry and function in the ageing heart: the MONICA/KORA Augsburg cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21:189-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou L, Liu Y, Wang Z, Liu D, Xie B, Zhang Y, Yuan M, Tse G, Li G, Xu G, Liu T. Activation of NADPH oxidase mediates mitochondrial oxidative stress and atrial remodeling in diabetic rabbits. Life Sci 2021;272:119240. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen PG, Jensen MT, Mogelvang R, Fritz-Hansen T, Galatius S, Biering-Sørensen T, Storgaard H, Vilsbøll T, Rossing P, Jensen JS. Impact of type 2 diabetes and duration of type 2 diabetes on cardiac structure and function. Int J Cardiol 2016;221:114-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li S, Liang M, Pan Y, Wang M, Gao D, Shang H, Su Q, Laher I. Exercise modulates heat shock protein 27 activity in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Life Sci 2020;243:117251. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seferović PM, Paulus WJ. Clinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: a two-faced disease with restrictive and dilated phenotypes. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1718-27, 1727a-1727c.

- Zhu Z, Li J, Si J, Ma B, Shi H, Lv J, et al. A large-scale genome-wide association analysis of lung function in the Chinese population identifies novel loci and highlights shared genetic aetiology with obesity. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2100199. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto Y, Urashima T, Kawachi F, Akaike T, Kusakari Y, Ida H, Minamisawa S. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease causes intrapulmonary venous arterialization in rats. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;154:1742-1753.e8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Egom EE, Feridooni T, Pharithi RB, Khan B, Shiwani HA, Maher V, El Hiani Y, Pasumarthi KBS, Ribama HA. A natriuretic peptides clearance receptor's agonist reduces pulmonary artery pressures and enhances cardiac performance in preclinical models: New hope for patients with pulmonary hypertension due to left ventricular heart failure. Biomed Pharmacother 2017;93:1144-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barrera CA, du Plessis AM, Otero HJ, Mahtab S, Githinji LN, Zar HJ, Zhu X, Andronikou S. Quantitative CT analysis for bronchiolitis obliterans in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents-comparison with controls and lung function data. Eur Radiol 2020;30:4358-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chong S, Lee KS, Chung MJ, Han J, Kwon OJ, Kim TS. Pneumoconiosis: comparison of imaging and pathologic findings. Radiographics 2006;26:59-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vander Weg MW, Rosenthal GE, Vaughan Sarrazin M. Smoking bans linked to lower hospitalizations for heart attacks and lung disease among medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2699-707. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ivanova O, Hoffmann VS, Lange C, Hoelscher M, Rachow A. Post-tuberculosis lung impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis of spirometry data from 14 621 people. Eur Respir Rev 2023;32:220221. [Crossref] [PubMed]