Multifocal Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors in a pediatric patient after kidney transplantation: a case description and literature analysis

Introduction

Antibody-mediated rejection after solid organ transplantation (SOT) is a major barrier to allograft survival (1). With the introduction and development of immunosuppressive therapy, acute rejection rates have steadily decreased, prolonging the survival of recipients and grafts after SOT (2). Patients require life-long immunosuppressive therapy after SOT, which could increase their susceptibility to infections from herpes viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (3).

Recipients develop various associated complications due to prolonged immunosuppression, and EBV tends to attack immunocompromised populations. EBV plays a key role in certain types of tumorigenesis, such as that of Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (4), with EBV-associated smooth muscle tumor (EBV-SMT) being particularly rare. EBV-SMT is virus-induced spindle cell tumor, and a 31-year study identified only three posttransplant EBV-SMT cases (5). Thus far, the three main subtypes of EBV-SMT include human immunodeficiency virus associated, transplantation associated, and congenital immunodeficiency disease associated (5,6).

The diagnosis of EBV-SMT by clinical presentation and radiological examination is challenging. To the best of our knowledge, a case of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) diagnosed by EBV-SMT has not been reported thus far. Therefore, we here describe the case, in which a nearly 3-year-old boy was diagnosed with multifocal EBV-SMTs after a second renal transplantation via gray-scale ultrasound and CEUS.

Case presentation

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was provided by the patient’s legal guardians for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

A boy who was almost 3 years of age with a history of two sequential allogeneic kidney transplants attended our hospital (Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology) with a fever, a cough, and shortness of breath 14 months after a second kidney transplant.

The child was delivered by emergency cesarean section at a gestational age of 33 weeks and 5 days due to oligohydramnios, and within 1 week after birth, his creatinine level had gradually increased to about 300 µmol/L. His father had a history of chronic kidney disease and, at the time of writing, is in generally good health. Genetic testing was performed on the patient and his parents to determine the cause of the elevated creatinine level. The genetic test results indicated that both the patient and his father had a variant in the AVIL gene locus, and the patient was diagnosed with congenital renal dysplasia.

The first allogeneic kidney transplantation was performed 7 months after birth. The patient received immunosuppression therapy, anti-infection treatment, and symptomatic therapy such as gastric protection after this transplantation. Nearly 5 months after the first transplantation, the child was admitted to the hospital with fever of no apparent cause. Laboratory examinations revealed that the EBV nuclear antigen IgG was at 13.5 U/mL, while the remaining results were negative. The EBV DNA level in peripheral blood mononuclear cells was 2.08×103 copies/mL. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) antibody test showed positivity for CMV IgG (48.1 U/mL) and CMV IgM (93 U/mL). The patient was considered to have both CMV and EBV infections and was discharged from the hospital after antiviral and antibacterial treatment, with regular follow-up. One year after the first transplantation, the child underwent the second transplantation at our hospital again due to loss of function of the transplanted kidney. He was prescribed mycophenolate sodium enteric-coated tablets, Prograf and Medrol, after the second transplantation.

The patient was readmitted to our hospital 14 months after the second transplantation for the development of a fever, a cough, and wheezing. The detailed laboratory data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1

| Parameters | Result | Reference range | Parameters | Result | Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte count (×109/L) | 13.51* | 4.4–11.9 | Interleukin 6 (pg/mL) | 8.70* | 0.1–2.9 |

| Monocyte count (×109/L) | 1.51* | 0.12–0.93 | Interleukin 4 (pg/mL) | 1.20 | 0.1–3.2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 115.0 | 112.0–149.0 | TNF-α (pg/mL) | 1.02 | 0.1–23 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 328.0 | 188.0–472.0 | IFN-γ | 3.24 | 0.1–18.0 |

| Glutamic pyruvic transaminase (U/L) | 12 | 9–50 | EBV-EA-IgG (U/mL) | <5.0 | <10 |

| Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (U/L) | 36 | 15–40 | EBV-VCA-IgG (U/mL) | >750.0* | <20 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 216 | <218 | EBV-VCA-IgM (U/mL) | 32.4* | <20 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 325* | 120–250 | EBV-NA-IgG (U/mL) | <3.0 | <5 |

| Carbamide (mmol/L) | 9.10* | 1.7–8.3 | EBV-DNA (peripheral blood mononuclear cells) (copies/mL) | 4.04×104* | (−) |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 36* | 59–104 | EBV-DNA (plasma) (copies/mL) | <5×102* | (−) |

| HBsAg | (−) | (−) | CD3+CD19− (%) | 46.60* | 58.7–75.0 |

| HCV Ab | (−) | (−) | CD3-CD19+ (%) | 12.91* | 13.8–26.7 |

| HIV Ab | (−) | (−) | CD3+CD4+ (%) | 14.42* | 28.3–46.5 |

| IgA (g/L) | 0.50 | 0.11–1.45 | CD3+CD8+ (%) | 21.25* | 16–29.5 |

| IgG (g/L) | 7.9 | 3.3–12.3 | CD3−/CD16+CD56+ (%) | 40.25* | 4.1–17.3 |

| IgM (g/L) | 0.55 | 0.33–1.75 | CD4+/CD8+ (%) | 0.68* | 1.06–2.54 |

| C3 (g/L) | 1.40* | 0.65–1.39 | CD3+CD4+HLA−DR+ (%) | 24.30* | 4.63–21.56 |

| C4 (g/L) | 0.25 | 0.16–0.38 | CD3+CD4+CD45RA+CCR7+ (%) | 18.98* | 57.03–89.13 |

| Interleukin 10 (pg/mL) | 24.45* | 0.1–5.0 | CD3+CD8+CD45RA+CCR7+ (%) | 19.65* | 31.16–91.79 |

*, abnormal values. HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; HIV Ab, human immunodeficiency virus antibody; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; C3, complement 3; C4, complement 4; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; IFN-γ, interferon γ; EBV-EA-IgG, Epstein-Barr virus early antigen IgG; EBV-VCA-IgG, Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen IgG; EBV-VCA-IgM, Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen IgM; EBV-NA-IgG, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen IgG.

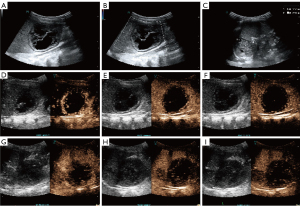

Chest computed tomography (CT) on admission showed several nodules and inflammation in both lungs, along with right interlobar fissure effusion. Abdominal gray-scale ultrasound was performed. The gray-scale ultrasound showed mixed cystic-solid lesions in the hepatic parenchyma, the splenic parenchyma, and the splenorenal space, with sizes of 5.3 cm × 4.7 cm, 3.3 cm × 2.3 cm, 5.1 cm × 4.5 cm, respectively. Color Doppler flow imaging did not show any blood flow signals within these lesions (Figure 1A-1C). To further define the nature of the lesions, the patient underwent CEUS after his parents signed informed consent. SonoVue (Bracco, Milan, Italy) was mixed with 5.0 mL of physiological saline, and then 0.3 mL of SonoVue contrast agent was injected intravenously through the head of the patient. The arterial phase of CEUS examination showed marginal enhancement of the above-mentioned lesions, with scattered contrast agent washing-in internally. The portal vein and delayed phases showed that the contrast agent in these mentioned lesions washed out gradually (Figure 1D-1I). Abdominal lesions were considered neoplastic on CEUS examination, but the exact nature of the lesions could not be determined.

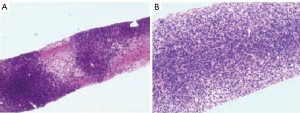

According to gray-scale ultrasound, CEUS, and assessment of the child’s vital signs, the puncture biopsy of a hepatic lesion was performed. Microscopic examination revealed that cells in the majority of the lesion areas had a dense distribution and were patchy. Meanwhile, in small areas, there were loose cells and interstitial edema, but no necrosis was observed. Microscopically, cells were oval and spindle shaped, with mild cytological atypia and less nuclear fission. The surrounding hepatic tissues were diffusely hydropic, with chronic inflammatory cells scattered in the interstitium. Finally, immunohistochemical results showed the following: EBNA2 (+), SMA (+), caldesmon (+), cyclin D1 (+), STAB2 (+), CD99 (+), FLI1 (+), CD3 (+), desmin (−), ERG (−), S-100 (−), SOX10 (−), ALK1A4 (−), STAT6 (−), hepatocyte (−), EMA (−), CD21 (−), CD34 (−), INI1 (+), P53 (+), and Ki-67 labelling index ~5%. EBV-encoded RNA in situ hybridization was positive. Overall, these results indicated a diagnosis of EBV-SMT (Figure 2).

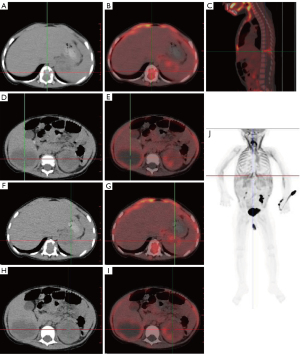

To further clarify whether other sites were metastatic foci, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) was performed in our hospital. 18F-FDG PET/CT showed multiple hypodense foci in the liver with mildly increased peripheral radioactivity uptake [standardized uptake value maximum (SUVmax) 1.35]. Low-density foci in the splenic parenchyma exhibited mildly elevated uptake (SUVmax 1.9). A mildly elevated peripheral radioactivity uptake (SUVmax 2.1) was observed around the mixed density foci in the splenorenal space. There was bone destruction of the thoracic spine (T11) with a soft tissue mass in the spinal canal (SUVmax 2.3) (Figure 3).

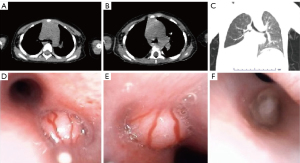

Chest CT was reviewed again nearly 1 month into this hospitalization, which showed a new soft-tissue density shadow of the right main bronchus compared to the previous one (Figure 4A-4C). The child’s condition appeared to progress rapidly. To further clarify the diagnosis, the patient underwent bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage. Bronchoscopy examination showed neoplasms in the carina tracheae, the right main bronchus, and the right middle trunk bronchus (Figure 4D-4F).

At the time of writing, the child is in poor condition and is being followed up on an ongoing basis (Figure 5).

Discussion

EBV is a γ-herpesvirus that is present in about 90–95% of the global population and is usually dormant. EBV preferentially infects epithelial cells and B cells (7). EBV is a transforming oncogenic virus that can immortalize B cells into lymphoblastoid cell lines, which can lead to diseases such as infectious mononucleosis, lymphomas, and epithelial cell carcinomas (8,9). However, EBV-SMT is one of the rarer mesenchymal tumors associated with EBV infection and is commonly seen in immunosuppressed populations. EBV-SMT was first reported in 1995 and clarified a correlation between EBV and SMT (10-12). It was only in 2006 that Deyrup et al. (13) provided the first detailed description of the histopathological and molecular features of EBV-SMT. To the best of our knowledge, given the rarity of this disease, there are no established radiological studies of EBV-SMT.

The malignant potential of EBV-SMT remains undetermined, but it can occur with multiple organ involvement including the endocranium, adrenal glands, lungs, liver, and spleen, etc. However, patients with multifocal EBV-SMTs are often considered to have multiple synchronized lesions. It has been demonstrated that multiple lesions do not arise due to metastasis but rather are multiple independent lesions; however, the mechanism of their detailed proliferation remains unclear (13). One theory of pathogenesis suggests that EBV enters cells via the CD21 receptor, while normal smooth muscle cells express the CD21 receptor or proteins with associated cross-reactive epitopes (14). EBV directly infects smooth muscle cells through CD21, thereby promoting the abnormal proliferation of smooth muscle cells (15). However, CD21 was not expressed in our patient. Perhaps there are other potential pathogenic mechanisms that remain to be discovered.

Most of the literature on EBV-SMT includes case reports and small-sample series. In a single-center study of over 31 years of EBV-SMT incidence among SOT recipients, there were only three cases of EBV-SMT identified in 5006 SOT recipients (5). EBV-SMT remains poorly recognized, and studies of its imaging manifestations are even rarer. Given the rapid progression of the child’s disease in our case, radiological examination may be particularly important both for early diagnosis and for the assessment of postoperative outcome. Since EBV-SMT can present with multiple-organ involvement, the appropriate imaging method may vary depending on the body part involved.

The central nervous system (CNS) is a recognized site for EBV-SMT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has proven to be an excellent and appropriate imaging method for EBV-SMT in the CNS. In a case of EBV-SMT in a patient with advanced HIV, MRI showed an isolated circular occupying lesion in the posterior medial aspect of the right posterior fossa, which was hyperenhanced with minimal areas of necrosis on postgadolinium T1-weighted imaging (16). Apart from the CNS, Fu et al. (17) described two patients with multiple EBV-SMTs in both lungs, both of whom underwent chest CT. Chest CT in both patients showed multiple nodules in both lungs. In our case, the patient’s most recent chest CT in comparison to that performed a month prior revealed small nodules visible in both lungs and a new soft-tissue mass in the right main bronchus, which suggested rapid progression of the disease. For the above CT manifestations in patients with EBV-SMT in the lungs, chest CT is a more prevalent follow-up imaging method than MRI for pulmonary EBV-SMT. Ultrasonography continues to evolve, but it is apparently not an appropriate imaging method for the CNS and the respiratory system at present.

However, for abdominal lesions, such as those located in the liver, spleen, and adrenal glands, ultrasonography has the advantages of real-time imaging, simplicity and affordability. With the development of ultrasonography, CEUS has greater advantages for the diagnosis and examination of the curative effect in abdominal lesions (18). Due to the rarity of EBV-SMT, to the best of our knowledge, this case report is the first to characterize CEUS in a patient with EBV-SMT. The contrast agent of CEUS is essentially blood pool contrast agent that reflects the microvascular perfusion of the lesion and surrounding normal tissues (19,20). In addition to the manifestation of CEUS in this case report described above, there are also a few case reports describing contrast-enhanced imaging of EMV-SMT at other sites. In the study by Johnson et al. (21), the patient with EBV-SMTs underwent contrast-enhanced CT, which showed multiple heterogeneously hypoenhancing liver masses with peripheral enhancement in the arterial phase. Hirama et al. (22) described a patient with a double lung transplantation who showed peripheral enhancement in the arterial phase for a hepatic lesion on contrast-enhanced CT. Although there were only two patients with EBV-SMT in the retrospective study by Hryhorczuk et al. (23), they both showed peripheral enhancement. This may suggest that peripheral enhancement of the arterial phase may be a more specific contrast-enhanced manifestation of EBV-SMT. This may be attributed to the abnormal proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the vessel wall near the tumor, which is typically characterized by a fascicular arrangement of spindle-shaped cells, resulting in the formation of a confined and partially fibrous pseudocapsule (13,24-26). However, due to the small number of EBV-SMT cases, which are mostly reported as case reports, this speculation remains to be substantiated. In the future, it is necessary to expand the sample size and conduct imaging series study on EBV-SMT. Moreover, the mixed cystic-solid lesions in the arterial phase also showed only scattered contrast agent filling inside. This may be due to a lack of internal blood supply due to excessive tumor growth, resulting in ischemia, hypoxia, and necrosis. Finally, the rapid progression of our patient’s condition was supported by the aforementioned chest CT findings.

There is currently no standard treatment for EBV-SMT, but surgical resection, chemotherapy, antiviral therapy, and immune reconstitution are the mainstays of treatment (27,28). Surgical resection of EBV-SMT is challenging due to its synchronous multifocal nature. EBV-SMT occurs in the immunocompromised patients, so combined immune reconstitution is particularly critical. CEUS is now widely used in the assessment of efficacy in tumor therapy (29,30). For assessing the response to EBV-SMT treatment, we believe that CEUS has certain advantages. For instance, the contrast agent used for CEUS is excreted from the body through respiration. The contrast agent of CEUS has a good safety profile due to the reduction of iodine contrast-induced nephropathy and gadolinium contrast–induced nephrogenic fibrosis (31,32). For liver and kidney transplant patients, CEUS should be recommended for the diagnosis of EBV-SMT compared with contrast-enhanced MRI and contrast-enhanced CT.

Conclusions

EBV-SMT is an extremely rare tumor that is usually a late complication of SOT. Due to its rarity, its treatment options have not been clarified. EBV-SMT requires a combination of CEUS, PET/CT, pathology, and EBV-encoded small RNA in situ hybridization. There are insufficient data to determine the specific imaging features of EBV-SMT. This article is the first to describe the CEUS features of a patient with EBV-SMT in detail. This can complement the existing known imaging features of EBV-SMT for clinicians and provide them with new perspectives on the early diagnosis and assessment of treatment efficacy for EBV-SMT.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1942/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was provided by the patient’s legal guardians for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Davis S, Cooper JE. Acute antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2017;31:47-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper JE. Evaluation and Treatment of Acute Rejection in Kidney Allografts. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;15:430-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ponticelli C. Herpes viruses and tumours in kidney transplant recipients. The role of immunosuppression. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:1769-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor GS, Long HM, Brooks JM, Rickinson AB, Hislop AD. The immunology of Epstein-Barr virus-induced disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2015;33:787-821. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stubbins RJ, Alami Laroussi N, Peters AC, Urschel S, Dicke F, Lai RL, Zhu J, Mabilangan C, Preiksaitis JK. Epstein-Barr virus associated smooth muscle tumors in solid organ transplant recipients: Incidence over 31 years at a single institution and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis 2019;21:e13010. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hussein K, Rath B, Ludewig B, Kreipe H, Jonigk D. Clinico-pathological characteristics of different types of immunodeficiency-associated smooth muscle tumours. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:2417-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pociupany M, Snoeck R, Dierickx D, Andrei G. Treatment of Epstein-Barr Virus infection in immunocompromised patients. Biochem Pharmacol 2024;225:116270. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Münz C. Cytotoxicity in Epstein Barr virus specific immune control. Curr Opin Virol 2021;46:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Magg T, Schober T, Walz C, Ley-Zaporozhan J, Facchetti F, Klein C, Hauck F. Epstein-Barr Virus(+) Smooth Muscle Tumors as Manifestation of Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders. Front Immunol 2018;9:368. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pritzker KP, Huang SN, Marshall KG. Malignant tumours following immunosuppressive therapy. Can Med Assoc J 1970;103:1362-5.

- McClain KL, Leach CT, Jenson HB, Joshi VV, Pollock BH, Parmley RT, DiCarlo FJ, Chadwick EG, Murphy SB. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in young people with AIDS. N Engl J Med 1995;332:12-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee ES, Locker J, Nalesnik M, Reyes J, Jaffe R, Alashari M, Nour B, Tzakis A, Dickman PS. The association of Epstein-Barr virus with smooth-muscle tumors occurring after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med 1995;332:19-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deyrup AT, Lee VK, Hill CE, Cheuk W, Toh HC, Kesavan S, Chan EW, Weiss SW. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors are distinctive mesenchymal tumors reflecting multiple infection events: a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 29 tumors from 19 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:75-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jenson HB, Montalvo EA, McClain KL, Ench Y, Heard P, Christy BA, Dewalt-Hagan PJ, Moyer MP. Characterization of natural Epstein-Barr virus infection and replication in smooth muscle cells from a leiomyosarcoma. J Med Virol 1999;57:36-46.

- Tardieu L, Meatchi T, Meyer L, Grataloup C, Bernard-Tessier A, Karras A, Thervet E, Lazareth H. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumor in a kidney transplant recipient: A case-report and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis 2021;23:e13456. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alfalahi A, Omar AI, Fox K, Spears J, Sharma M, Bharatha A, Munoz DG, Suthiphosuwan S. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Smooth-Muscle Tumor of the Brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2024;45:850-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu XY, Gao X, Zhao CL, Qi XF, Ouyang XJ, Zhu LH, Wang D, Qu LJ, Ye XZ. Pulmonary Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumor after kidney transplantation: two case reports with review of differential diagnosis. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2024;65:107-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Jang HJ, Khalili K, Kim TK, Atri M. Successful Integration of Contrast-enhanced US into Routine Abdominal Imaging. Radiographics 2018;38:1454-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kong WT, Wang WP, Huang BJ, Ding H, Mao F. Value of wash-in and wash-out time in the diagnosis between hepatocellular carcinoma and other hepatic nodules with similar vascular pattern on contrast-enhanced ultrasound. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:576-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao H, Fang L, Chen L, Zhan J, Diao X, Liu Y, Lu C, Zhang Z, Chen Y. The independent indicators for differentiating renal cell carcinoma from renal angiomyolipoma by contrast-enhanced ultrasound. BMC Med Imaging 2020;20:32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson BM, Iskandar JP, Farha N, Yerian L, Modaresi Esfeh J, Lindenmeyer C. Hepatic Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Smooth Muscle Tumor in a Heart and Liver Transplant Recipient. ACG Case Rep J 2022;9:e00782. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirama T, Tikkanen J, Pal P, Cleary S, Binnie M. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors after lung transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2019;21:e13068. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hryhorczuk AL, Kim HB, Harris MH, Vargas SO, Zurakowski D, Lee EY. Imaging findings in children with proliferative disorders following multivisceral transplantation. Pediatr Radiol 2015;45:1138-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramdial PK, Sing Y, Deonarain J, Hadley GP, Singh B. Dermal Epstein Barr virus--associated leiomyosarcoma: tocsin of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in two children. Am J Dermatopathol 2011;33:392-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramdial PK, Sing Y, Deonarain J, Vaubell JI, Naicker S, Sydney C, Hadley LG, Singh B, Kiratu E, Gundry B, Sewram V. Extra-uterine myoid tumours in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a clinicopathological reappraisal. Histopathology 2011;59:1122-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jonigk D, Laenger F, Maegel L, Izykowski N, Rische J, Tiede C, Klein C, Maecker-Kolhoff B, Kreipe H, Hussein K. Molecular and clinicopathological analysis of Epstein-Barr virus-associated posttransplant smooth muscle tumors. Am J Transplant 2012;12:1908-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lau KW, Hsu YW, Lin YT, Chen KT. Role of surgery in treating epstein-barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumor (EBV-SMT) with central nervous system invasion: A systemic review from 1997 to 2019. Cancer Med 2021;10:1473-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paez-Nova M, Andaur K, García-Ballestas E, Bustos-Salazar D, Moscote-Salazar LR, Koller O, Valenzuela S. Primary intracranial smooth muscle tumor associated with Epstein-Barr virus in immunosuppressed children: two cases report and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst 2021;37:3923-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan X, Fu X, Gui Y, Chen X, Cheng Y, Dai M, Wang W, Xiao M, Tan L, Zhang J, Shao Y, Wang H, Chang X, Lv K. Development and validation of a nomogram model based on pretreatment ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound to predict the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with borderline resectable or locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Imaging 2024;24:13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto K, Moriyasu F, Saito K, Rognin N, Kamiyama N, Furuichi Y, Imai Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib: early detection of treatment response and major adverse events by contrast-enhanced US. Liver Int 2013;33:605-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Q, Yang K, Ji Y, Liu H, Fei X, Zhang Y, Li J, Luo Y. Safety Analysis of Adverse Events of Ultrasound Contrast Agent Lumason/SonoVue in 49,100 Patients. Ultrasound Med Biol 2023;49:454-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- David E, Del Gaudio G, Drudi FM, Dolcetti V, Pacini P, Granata A, Pretagostini R, Garofalo M, Basile A, Bellini MI, D'Andrea V, Scaglione M, Barr R, Cantisani V. Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound Compared with MRI and CT in the Evaluation of Post-Renal Transplant Complications. Tomography 2022;8:1704-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]