Diagnostic challenges in emergency stroke: a case series

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide and a major cause of disability (1,2). Most strokes are due to reduction or interruption of blood flow to the brain, which is called ischemic stroke (IS). Symptoms of IS may include sudden-onset numbness or weakness in an arm or leg, facial droop, speech disturbances, trouble with balance or coordination, and loss of vision. Acute IS (AIS) is a medical emergency caused by decreased blood flow to the brain, which results in damage to brain cells (3). The most effective treatment for AIS is intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) and mechanical thrombectomy (MT). It is a medical emergency that requires a timely and accurate diagnosis, because the ratio of patients with AIS who can benefit from acute IVT or MT will decrease quickly as time elapses (4,5).

Most cases of IS are easily diagnosed, but some stroke mimics (SMs) can be misdiagnosed as AIS and then receive unnecessary examinations and IVT. SMs refer to a variety of medical conditions that present with symptoms similar to those of AIS, but actually are caused by other diseases. It is challenging to differentiate SMs from true strokes in an emergency because they share similar clinical presentations. They include functional disorders, migraine, seizure, spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH), myelopathy, metabolic disorders such as hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and so on (6-9). Stroke chameleons (SCs) comprise a variety of conditions that initially present with symptoms suggesting other diagnoses but are later revealed to be acute strokes. Metabolic disorders can sometimes mask the symptoms of AIS, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment. It is crucial to identify the situation promptly in order for patients to receive appropriate treatment. Although the risk of damage from IVT in SMs is generally low (10), it is important to note that some patients may incur severe adverse events during treatment, such as aortic dissection, SSEH, or infective endocarditis. Such events will worsen the condition, even result in death, which increases unnecessary medical expenses. Consequently, there is a need for a timely and accurate diagnosis so patients can receive the proper treatment during the acute phase.

In order to improve identification of real or false stroke at the early stage, we introduce a rare case series of SMs and SCs innovatively by subject modes, including epileptic cases, metabolic disorders, and myelopathy. We present this article in accordance with the AME Case Series reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1640/rc).

Case presentation

Epileptic cases

Case 1

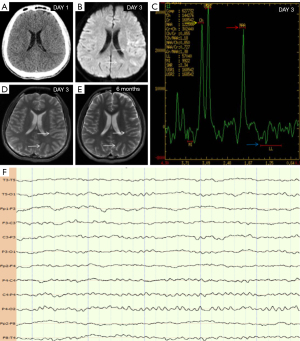

An 18-year-old male patient presented with weakness in his right upper limb and dysarthria for a duration of 1 day. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 1. A head computed tomography (CT) was performed, which returned normal results (Figure 1A). Subsequently, he was diagnosed with AIS. On day 3 of hospitalization, he experienced an epileptic seizure, fever, and headache. Video electroencephalogram (VEEG) showed that the background of the electroencephalogram (EEG) was asymmetrical, and the left posterior head showed a lower amplitude than the opposite side, but no epileptic discharges were observed (Figure 1F). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the left temporo-occipital lobe was swollen; there was also hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI; Figure 1B, white arrows) and T2 (Figure 1D, white arrows). The artery was normal. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) showed a slight increase in Cho peak (Figure 1C, yellow arrow), a slight decrease in N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) peak (Figure 1C, red arrow), a lactate peak was visible (Figure 1C, blue arrow). The radiologist considered that the diagnosis was mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS); however, the genetic analysis of MELAS syndrome was normal. The patient was positive for anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid. And the symptoms were improved by glucocorticosteroid therapy. MRI suggested that the left temporo-occipital lobe returned to normal after 6 months (Figure 1E, white arrows). The final diagnosis was MOG antibody-positive cerebral cortical encephalitis with symptomatic epilepsy.

Case 2

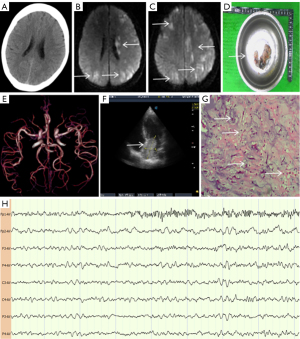

A 53-year-old woman presented with sudden loss of consciousness and convulsions in her all limbs for 2 minutes, followed by right hemiparesis. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 2. Head CT was normal (Figure 2A), and the patient was initially diagnosed with Todd’s paralysis, but she also showed a left gaze preference. Her symptoms did not support the localized signs of irritant lesions by epilepsy but were consistent with the localized signs of cerebral hemispheric damage by AIS. Therefore, the patient was given IVT therapy; however, the symptoms did not improve significantly. VEEG revealed involuntary movement in the left limbs, accompanied by abnormal spike and slow waves in the left prefrontal cortex (Figure 2H, Fp1-AV). On the fourth day of illness, DWI showed multiple new cerebral infarctions on both sides of the brain (Figure 2B,2C, white arrows). There was no arterial occlusion (Figure 2E). Cardiac color Doppler ultrasound detected a tumor in the left atrium (Figure 2F, white arrow) which was subsequently removed surgically (Figure 2D, white arrow). Pathological analysis indicated the presence of a large number of round or polygonal cells (Figure 2G, white arrows, hematoxylin and eosin staining, 200× magnification). When combined with immunohistochemical data, this suggested a left cardiac myxoma. The final diagnoses were acute cerebral embolism (caused by a left cardiac myxoma) and symptomatic epilepsy.

Case 3

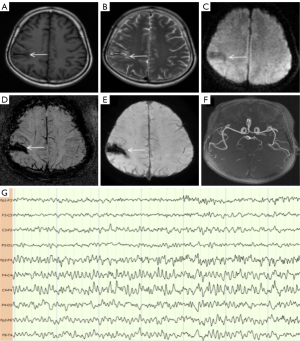

A 59-year-old woman presented with a history of intracranial hemorrhage due to craniocerebral trauma over 8 years; she had no high-risk factors for cerebrovascular disease. She had experienced repeated episodes of numbness and weakness in her left limbs, dizziness, and dysarthria; these symptoms self-alleviated on each occasion. The patient was diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack (TIA). Antiplatelet therapy was ineffective. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 3. MRI showed a lesion on the right parietal lobe; there was also hypointensity on T1 (Figure 3A, white arrow) and DWI (Figure 3C, white arrow), and hyperintensity on T2 (Figure 3B, white arrow). Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) showed hypointensity of the right parietal lobe on the phase image (Figure 3D, white arrow) and amplitude images (Figure 3E, white arrow). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) was normal (Figure 3F). All these findings indicated that the lesion was caused by intracerebral hemorrhage. The VEEG revealed epileptic discharges on the Rolandic area and right frontal (Figure 3G, FP2-F4 to C4-P4) when the patient experienced numbness and weakness in the left limbs. The symptoms disappeared after treatment with antiepileptic medication. The final diagnosis was symptomatic epilepsy, caused by intracerebral hemorrhage.

Metabolic disorders

Case 4

An 86-year-old woman presented with weakness in her right limbs for 5 hours; she was also experiencing lethargy, right hemiplegia, no eye deviation, and no facial or tongue paralysis. She had a negative Babinski sign. Initial laboratory analyses showed a blood glucose level of 565 mg/dL. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 4. Head CT was normal (Figure 4A). Right hemiparesis did not improve after the blood glucose levels had returned to normal following the administration of insulin. Consequently, she was diagnosed with AIS and treated with antiplatelet agents; subsequently, the right hemiparesis improved gradually. However, MRA revealed that there was no arterial occlusion (Figure 4B), and DWI did not reveal acute infarction (Figure 4C,4D). The final diagnosis was type 2 diabetes.

Case 5

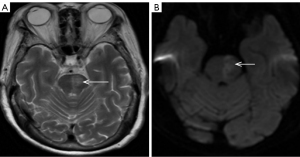

A 64-year-old woman had a history of type 2 diabetes for 5 years. She presented with weakness in her right limbs for 2 hours. She was also experiencing lethargy, right gaze deviation, right facial and tongue paralysis, right hemiplegia, and a right Babinski sign positive. Her blood glucose level was 667 mg/dL, and head CT was normal. At this point, the patient was diagnosed with AIS and administered IVT. However, when the blood glucose had returned to normal following the administration of insulin, the patient’s symptoms did not improve. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 5. MRI revealed hyperintensity in left pons on T2 (Figure 5A, white arrow) and DWI (Figure 5B, white arrow). The final diagnoses were acute pons infarction and type 2 diabetes.

Case 6

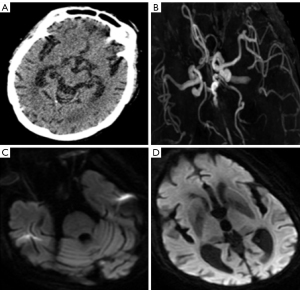

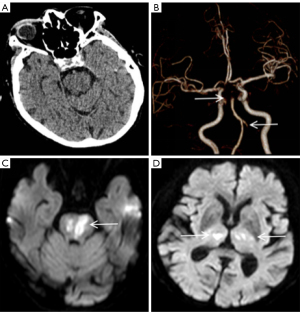

An 86-year-old woman arrived at the hospital unconscious; she had experienced weakness in her all limbs for 10 hours. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 6. Head CT was normal (Figure 6A). The level of serum potassium was 6.81 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.5 mmol/L). We considered that the unconscious state was due to hyperkalemia. The level of serum potassium was recovered after therapy, but the unconscious state persisted. CT angiography (CTA) suggested that the left vertebral artery, the top of the basilar artery, and the bilateral posterior cerebral arteries were all occluded (Figure 6B, white arrows). MRI showed hyperintensity in the thalamus, mesencephalon, and pons by DWI (Figure 6C,6D, white arrows). However, by this time, the opportunity for MT had been missed. The final diagnoses were multiple acute cerebral infarction and hyperkalemia.

Myelopathy

Case 7

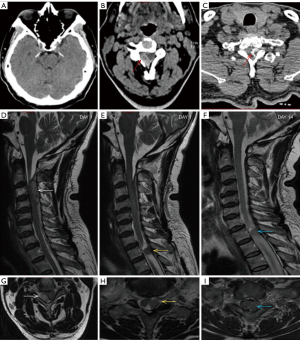

A 59-year-old man presented with sudden weakness in his all limbs and slight neck pain for 2 hours. He had a history of hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease, without a history of neck trauma, neck massage, or cervical spondylosis. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 7. Head CT was normal (Figure 7A); consequently, the patient was diagnosed with AIS and was prepared to receive IVT. Over time, the neck pain became gradually aggravated and with a hypoesthesia below left T4. A quick-check contrast-enhanced CT of the cervical vertebra was performed and revealed a mild hyperintensity lesion at C2–C4 (Figure 7B, red arrow), and a mixed density lesion at T1 (Figure 7C, red arrow). MRI revealed a SSEH at C2–C4 (Figure 7D,7G, white arrows) and a spinal meningioma at T1 (Figure 7E,7H, yellow arrows). Finally, the patient did not receive surgical treatment. On day 14 of hospitalization, the SSEH at C2–C4 had disappeared spontaneously, but the spinal meningioma at T1 was still evident (Figure 7F,7I, blue arrows). The final diagnoses were SSEH and spinal meningioma.

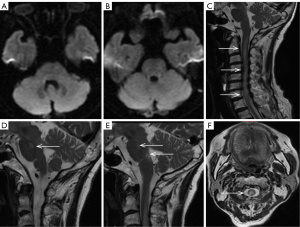

Case 8

A 68-year-old man presented with sudden numbness and weakness in his right limbs for 3 hours; he was subsequently diagnosed with AIS and was prepared to receive IVT. However, he had a history of protrusion of the lumbar intervertebral disc, along with repeated episodes of numbness and weakness in the right lower limb. Therefore, we suspected that the patient might have experienced SM. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 8. DWI showed no acute cerebral infarction (Figure 8A-8C). MRI showed protrusion of the cervical intervertebral disc at C5/6 and C6/7 (Figure 8D, white arrows), and the bilateral nerve roots were pressed (Figure 8F, white arrow). MRI also showed protrusion of the lumbar intervertebral disc at L3/4 and L4/5 (Figure 8E, white arrows), and the bilateral nerve roots were pressed (Figure 8G, white arrow). The final diagnoses were cervical spondylosis and protrusion of lumbar intervertebral disc.

Case 9

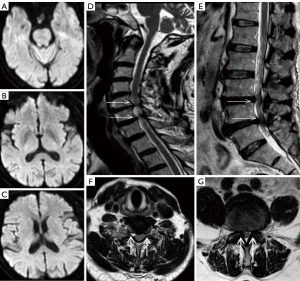

A 72-year-old woman presented with weakness in her right limbs for 5 days. Head CT was normal; she was diagnosed with AIS and treated with antiplatelet agents. The patient’s examination results are shown in Figure 9. DWI showed no acute cerebral infarction (Figure 9A,9B). The patient experienced neck pain on day 3 of hospitalization. MRI T2-weighted imaging showed hyperintensity at C1–T2 (Figure 9C,9F, white arrows) and the pons (Figure 9D,9E, white arrows). The serum and cerebrospinal fluid were positive for aquaporin 4 (AQP4) antibody. The final diagnosis was neuromyelitis optica (NMO).

The above cases are presented in Table 1 to illustrate the admission date as well as the timings of the CT, brain MRI, spinal MRI, and VEEG.

Table 1

| Items | Admission date | CT | Brain MRI | Spinal marrow MRI | VEEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Jan 16, 2021 | Day 1 | Day 3 and 6 months | Day 7 | |

| Case 2 | Apr 18, 2019 | Day 1 | Day 5 | Day 1 | |

| Case 3 | Jul 1, 2018 | Day 2 | Day 3 | ||

| Case 4 | Feb 19, 2020 | Day 1 | Day 3 | ||

| Case 5 | May 28, 2021 | Day 3 | |||

| Case 6 | Jan 17, 2021 | Day 1 | Day 2 | ||

| Case 7 | Sep 26, 2020 | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 3 | |

| Case 8 | Jan 6, 2021 | Day 2 | Day 2 | ||

| Case 9 | Dec 4, 2020 | Day 2 | Day 6 |

The table shows the admission date of every case, and the timing of different examinations. CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; VEEG, video electroencephalogram.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was provided by the patients for publication of this case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Epilepsy cases

There are many diseases showing an initial manifestation of epileptiform seizure, such as hypoglycemia, intracranial tumors, encephalitis, stroke, metabolic disorders, and Adams-Stokes syndrome. Todd’s paralysis is often easily misdiagnosed as acute stroke, especially if the seizure was not witnessed. Similarly, epileptic seizure may represent an initial manifestation of acute stroke. The magnetic resonance of the head combined with long-term VEEG monitoring can help when it is difficult to distinguish epilepsy from cerebrovascular disease.

The combination of head CT perfusion (CTP) imaging and EEG can also help to distinguish cerebral infarction from epilepsy. Most IS patients exhibit significant severe focal hypoperfusion and slower EEG rhythms. A recent study of 11 SM patients with seizure etiology showed that most cases exhibited a hyperperfusion pattern and sharp EEG waves; only a few cases showed a slow EEG rhythm and slight hypoperfusion below the threshold for IS (11). However, it is important to note that it may involve limb-shaking TIA rather than seizure if the repetitive involuntary jerky limb movements are triggered by an orthostatic position change or exercise (12). According to the guidelines published by the European Stroke Organization (ESO), IVT should be administered to patients with AIS of <4.5 hours duration who have seizures accompanied with stroke, and for whom SM or significant head trauma are not suspected (13).

Metabolic disorders

Metabolic disorders, such as hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, and hypokalemia, can be presented with a myriad of clinical manifestations, including SMs. In a previous study, Singh et al. reported that hypoglycemia could present with repeated episodes of TIA (14). Meanwhile, we should consider that metabolic disorders may occasionally be associated with real stroke, thus covering up the symptoms of AIS. When a case involves hemiplegia with hyperglycemia, the diagnosis may be AIS if head CT is normal and hemiparesis does not improve after the blood glucose levels have returned to normal. However, sometimes things do transpire that way, just as in case 4. It has been reported that hyperglycemia can present as a left middle cerebral artery stroke associated with lethargy, global aphasia, left eye deviation, and right hemiparesis (15).

The question arises, therefore, as to what to do with a patient with hemiplegia and hyperglycemia in the acute phase. According to the guidelines published by ESO, IVT should be administered to patients with an AIS <4.5 hours in duration and blood glucose levels above 22.2 mmol/L (400 mg/dL) (13). We recommend that early MRI and/or CTA should be performed first, examining arterial blood gas analysis and serum osmolality at the same time in order to rule out diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) (16). This will ensure that both cases are properly managed and that time-sensitive interventions such as thrombolysis and thrombectomy can be considered.

Myelopathy

Myelopathy can present with acute hemiparesis, paraplegia, or tetraplegia, and can be easily misdiagnosed as acute stroke, with subsequent, unnecessary implementation of IVT (17). Therefore, it is important that a patient’s medical history and physical examination are acquired in specific detail. When a patient experiences a stroke-like episode, in addition to checking the sensory system in the limbs, we should also check the trunk sensation carefully, in order to assess whether the patient is experiencing spinal cord damage, especially when patients experience neck pain, shoulder pain, or back pain. However, we should acknowledge that some patients do not have these symptoms at the beginning, or they may only feel slight pain. Therefore, a quick-check MRI of head and cervical vertebra should be performed as soon as possible. If a quick-check MRI cannot be performed, then a quick-check contrast-enhanced CT should be considered as it may also be able to identify a lesion.

Conclusions

When we are unable to judge whether a patient has experienced acute stroke in the early phase, multimodal CT should be used as this can confirm the diagnosis of an intracranial large artery occlusion or perfusion abnormalities (18). Head DWI can reveal ischemic changes very early, but it is not widely available in an emergency (19). SMs are prone to misdiagnosis, especially in the emergency department. Although the risk of damage from IVT in SMs is very low (10), in order to avoid unnecessary examinations and treatments, we should prevent patients from taking long-term antiplatelet therapy. It is still necessary to identify SMs as early as possible. SCs are easy to ignore when accompanied by other diseases that can cover up the symptoms of AIS. Such patients might not be treated in the acute phase leading to a gradual worsening over time. Importantly, diagnostic accuracy should not be pursued in an excessive manner because this may delay the timely treatment of patients. Using another 15 minutes to improve diagnostic accuracy may potentially cause harm in 99% of patients but may identify the 1% of patients who will ultimately receive (and tolerate) unnecessary IVT (20). Therefore, it may create more risk to delay IVT to exclude SM than to provide IVT in cases with SM.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the AME Case Series reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1640/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1640/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Yang Q, Tong X, Schieb L, Vaughan A, Gillespie C, Wiltz JL, King SC, Odom E, Merritt R, Hong Y, George MG. Vital Signs: Recent Trends in Stroke Death Rates - United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:933-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mercy UC, Farhadi K, Ogunsola AS, Karaye RM, Baguda US, Eniola OA, Yunusa I, Karaye IM. Revisiting recent trends in stroke death rates, United States, 1999-2020. J Neurol Sci 2023;451:120724. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walter K. What Is Acute Ischemic Stroke? JAMA 2022;327:885. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Man S, Xian Y, Holmes DN, Matsouaka RA, Saver JL, Smith EE, Bhatt DL, Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC. Association Between Thrombolytic Door-to-Needle Time and 1-Year Mortality and Readmission in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. JAMA 2020;323:2170-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Snyder T, Agarwal S, Huang J, Ishida K, Flusty B, Frontera J, et al. Stroke Treatment Delay Limits Outcome After Mechanical Thrombectomy: Stratification by Arrival Time and ASPECTS. J Neuroimaging 2020;30:625-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Granato A, D'Acunto L, Ajčević M, Furlanis G, Ukmar M, Mucelli RAP, Manganotti P. A novel computed tomography perfusion-based quantitative tool for evaluation of perfusional abnormalities in migrainous aura stroke mimic. Neurol Sci 2020;41:3321-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suzuki M, Kano Y, Watanuki S, Murata K. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma with hemiparesis: A stroke mimic. Clin Case Rep 2024;12:e9478. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bathla G, Policeni B, Agarwal A. Neuroimaging in patients with abnormal blood glucose levels. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:833-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keselman B, Cooray C, Vanhooren G, Bassi P, Consoli D, Nichelli P, Peeters A, Sanak D, Zini A, Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Mazya MV. Intravenous thrombolysis in stroke mimics: results from the SITS International Stroke Thrombolysis Register. Eur J Neurol 2019;26:1091-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali-Ahmed F, Federspiel JJ, Liang L, Xu H, Sevilis T, Hernandez AF, Kosinski AS, Prvu Bettger J, Smith EE, Bhatt DL, Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Peterson ED, Xian Y. Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator in Stroke Mimics. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2019;12:e005609. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manganotti P, Furlanis G, Ajčević M, Polverino P, Caruso P, Ridolfi M, Pozzi-Mucelli RA, Cova MA, Naccarato M. CT perfusion and EEG patterns in patients with acute isolated aphasia in seizure-related stroke mimics. Seizure 2019;71:110-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pitton Rissardo J, Fornari Caprara AL. Limb-Shaking And Transient Ischemic Attack: A Systematic Review. Neurologist 2024;29:126-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, De Marchis GM, Fonseca AC, Padiglioni C, de la Ossa NP, Strbian D, Tsivgoulis G, Turc G. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J 2021;6:I-LXII. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh RJ, Doshi D, Barber PA. Hypoglycemia Causing Focal Cerebral Hypoperfusion and Acute Stroke Symptoms. Can J Neurol Sci 2021;48:550-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah NH, Velez V, Casanova T, Koch S. Hyperglycemia presenting as left middle cerebral artery stroke: a case report. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2014;7:9-12.

- Marren SM, Beale A, Yiin GS. Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state as a stroke cause or stroke mimic: an illustrative case and review of literature. Clin Med (Lond) 2022;22:83-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watanabe M, Abe E, Sakamoto K, Horikoshi K, Ueno H, Nakao Y, Yamamoto T. Analysis of a Spontaneous Spinal Epidural Hematoma Mimicking Cerebral Infarction: A Case Report and Review of the Literatures. No Shinkei Geka 2020;48:683-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonney PA, Walcott BP, Singh P, Nguyen PL, Sanossian N, Mack WJ. The Continued Role and Value of Imaging for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurosurgery 2019;85:S23-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liberman AL, Prabhakaran S. Stroke Chameleons and Stroke Mimics in the Emergency Department. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017;17:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moulin S, Leys D. Stroke mimics and chameleons. Curr Opin Neurol 2019;32:54-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]