18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-compute tomography parameters for predicting the prognosis and toxicity in children and young adults with large B-cell lymphoma receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) are common tumors among children and young adults (1). Although chemotherapy can significantly improve survival, with a 5-year event-free survival >80%, the prognosis is poor for patients who relapse or respond poorly to frontline chemotherapy [overall survival (OS) rate ≤25%] (2). Moreover, high-dose chemotherapy may induce delayed effects including secondary malignancies, chronic health conditions, and infertility (3,4).

As a novel immune therapy, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has achieved remarkable results in many types of malignancies, especially in relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), and the therapeutic effects can be enduring (5-7). However, the majority of patients do experience relapse (8,9). Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) are common immune-related adverse events that must be closely monitored, as they can be fatal (10). Therefore, it is important to identify patients with poorer prognoses and those at risk for severe adverse effects before CAR T-cell therapy is administered.

As a combination of morphologic and functional imaging, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) is critical to diagnosis, staging, evaluation of response, and prediction of long-term survival in patients LBCL (11-13). Studies have assessed the prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters, such as total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV), maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), and total lesion glycolysis (TLG), before CAR T-cell infusion in patients with lymphoma (14-16). Clinical-laboratory characteristics such as Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and C-reactive protein (CRP) level have also been demonstrated to be associated with patient prognosis. Furthermore, a few studies have investigated the relationship between PET/CT metabolic parameters and the adverse effects caused by CAR T cells. However, these studies focused primarily on older adults, and thus studies on the relationship between metabolic parameters of pretreatment 18F-FDG PET/CT and the prognosis and adverse effects in children and young adults with LBCL are lacking.

Therefore, in this study, we retrospectively collected clinical characteristics, laboratory examinations, and PET/CT metabolic parameters of patients under 30 years old who received CAR T-cell infusion and investigated the correlation of these indices with prognosis and treatment-related adverse events. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1737/rc).

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Friendship Hospital of Capital Medical University (No. 2024-P2-259-01) and followed the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The other participating hospital, Beijing GoBroad Boren Hospital, was informed of and agreed with the study. The requirement of individual consent for this retrospective and observational analysis was waived. We analyzed PET data between January 2020 and September 2023 acquired from Beijing Friendship Hospital of Capital Medical University and Beijing GoBroad Boren Hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) age ≤30 years; (II) diagnosis of relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; (III) administration of second-generation CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy (17,18); and (IV) 18F-FDG PET/CT scan performed within 1 month before CAR T-cell infusion. Patients associated with other malignancies or lost to follow-up were excluded.

Clinical characteristics

The following characteristics were collected: age, gender, pathology type, stage (Ann Arbor staging system for adults and the international pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma staging system for children) (19), B symptoms, ECOG score, age-adjusted international prognostic index (aaIPI), therapy lines, bridging therapy, levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and ferritin, and CRP, CRS, and ICANS stage. Efficacy after 1 month of CAR T-cell infusion was evaluated and recorded. Laboratory data were collected within 1 week before CAR T-cell infusion.

PET/CT protocol and measurement

On average, 18F-FDG PET/CT was carried out 17±6 days prior to the infusion of CAR T cells. Before the examination, informed consent was signed by all patients >18 years old or by the guardians of patients ≤18 years old. PET/CT examinations were performed using a uMI Vista scanner (United Imaging, Shanghai, China), and the 18F-FDG had a ≥95% radiochemical purity. Patients were required to fast for at least 6 hours before injection of the tracer and to ensure that fasting blood glucose was ≤11.1 mmol/L. The active concentration of 18F-FDG was 3.70–5.55 MBq/kg (0.10–0.15 mCi/kg). Scanning was performed approximately 60 minutes after injection. Two experienced nuclear physicians independently analyzed PET/CT scans using LIFEx v.7.5.12 software (20). When their opinions differed, senior nuclear medicine physicians made the final decision. As recommended, each lesion was measured individually and then segmented based on the threshold, which was 41% of the SUVmax (21). The following metabolic parameters were recorded: SUVmax, defined as the maximum SUVmax among all lesions; TMTV (mL), defined as the sum of all metabolic volumes; and TLG, defined as the sum of TLG of all lesions.

Follow-up

Patients were followed up via query of the medical record system or by telephone. Efficacy was assessed using PET/CT, CT, or MRI after 1 month of CAR T-cell infusion, and the objective response rate (ORR) included partial or complete response. The cut-ff date for follow-up was March 31, 2024. The main endpoint included progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. PFS was regarded as the period starting from CAR T-cell infusion and ending at the time of disease relapse, progression, death by any cause, or arrival of the follow-up cutoff date. PFS was defined as the time between CAR T-cell infusion and disease relapse, progression, death from any cause, or arrival of the follow-up cutoff date. OS was defined as the time between CAR T-cell infusion and death from any cause or follow-up cutoff date. The occurrence and severity of CRS and ICANS were also collected from the medical record system.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0, (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism v. 10.2.3.347 (Dotmatics, Boston, MA, USA; www.graphpad.com). Qualitative data are expressed as percentages. Quantitative data that conformed to a normal distribution are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while data that did not conform to a normal distribution are expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Laboratory examination data were analyzed by transforming them into dichotomous variables using the upper limit of normal values as the threshold. According to the literature, the following prognostic clinical features were dichotomized [ECOG 2–3 vs. 0–1 (15,22,23), stage III–IV vs. I–II (23), aaIPI 2–3 vs. 0–1] (16). The CRS and ICANS were divided into grade 0–1 and grade 2–4. For PET parameters, the optimal cutoff values were calculated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for PFS, and these threshold values were also applied to the analysis of OS and toxicities. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate PFS and OS, and the log-rank test was used to compare the prognostic value of clinical indicators and PET/CT metabolic parameters for PFS and OS. Univariate and stepwise multivariate analyses were performed using Cox proportional models to select prognostic characteristics for PFS and OS, and hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were recorded. The Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ) was determined for every pair of variables that had prognostic significance. Factors associated with CRS and ICANS were analyzed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Forty-five patients were included in this study (Figure 1). The detailed clinical and laboratory characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median SUVmax was 11.5 (IQR, 4.8–21.4). The median TMTV was 47.0 mL, with an IQR of 15.0–124.9 mL. Meanwhile, the median TLG was 214.1, and its IQR was 57.9–771.2. Among the patients, 27 (60%) achieved complete response, 9 (20%) achieved partial response, 3 (6.7%) experienced stable disease, and 6 (13.3%) experienced disease progression. The ORR was 80%. The median follow-up time was 13.9 months (95% CI: 6.613–24.687). Moreover, 21 (46.7%) patients experienced relapse or progression during the follow-up period, and 15 (33.3%) patients died. The median PFS was 15.6 months (95% CI, 7.497–20.303), and the 1-year PFS was 60%. The median OS was not reached (NR), and the 1-year OS was 73.3%.

Table 1

| Feature | Values (n=45) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 31 (68.9) |

| Female | 14 (31.1) |

| Age (years) | 17.4±7.4 |

| Lymphoma subtype | |

| BL | 16 (35.6) |

| PMBCL | 12 (26.7) |

| DLBCL | 17 (37.8) |

| Bridging therapy | |

| Yes | 35 (77.8) |

| No | 10 (22.2) |

| Previous lines of systemic therapy | |

| 2 | 17 (37.8) |

| ≥3 | 28 (62.2) |

| B symptoms | |

| Yes | 8 (7.8) |

| No | 37 (82.2) |

| Stage | |

| No disease | 2 (4.4) |

| I–II | 14 (31.1) |

| III–IV | 29 (64.4) |

| ECOG score | |

| 0–1 | 38 (84.4) |

| 2–3 | 7 (15.6) |

| aaIPI | |

| 0–1 | 31 (68.9) |

| 2–3 | 14 (31.1) |

| LDH | |

| Normal | 30 (66.7) |

| > UNL | 15 (33.3) |

| CRP | |

| Normal | 31 (68.9) |

| > UNL | 14 (31.1) |

| Ferritin | |

| Normal | 10 (22.2) |

| > UNL | 35 (77.8) |

| Adverse events | |

| CRS | |

| Grade 0–1 | 30 (66.7) |

| Grade 2–4 | 15 (33.3) |

| ICANS | |

| Grade 0–1 | 39 (86.7) |

| Grade 2–4 | 6 (13.3) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. BL, Burkett lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; PMBCL, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; aaIPI, age-adjusted International Prognostic Index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; UNL, upper normal limit; CRP, C-reactive protein; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome.

Threshold values of 18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters

For the ROC curves for PFS, the area under the curve (AUC) of the SUVmax was 0.674 (95% CI: 0.515–0.832; P=0.047), the AUC for TMTV was 0.718 (95% CI: 0.568–0.869; P=0.012), and the AUC for TLG was 0.680 (95% CI: 0.552–0.837; P=0.039) (Figure 2). Therefore, the optimal threshold value was 13.8 for SUVmax, 101.4 mL for TMTV, and 333.6 for TLG.

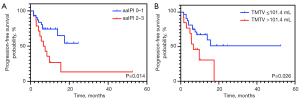

Prognostic value

According to the univariate analysis, aaIPI 2–3, SUVmax >13.8, and TMTV >101.4 mL were significantly associated with shorter PFS. In the multivariate analysis, aaIPI 2–3 and TMTV >101.4 mL remained independent risk factors of PFS (Table 2). The median PFS was significantly longer for the aaIPI 0–1 group than for the aaIPI 2–3 group (NR vs. 6.6 months; P=0.014) (Figure 3A). When the two groups were compared, the median PFS was substantially longer for the group with TMTV ≤101.4 mL than for the group with TMTV >101.4 mL (NR vs. 6.2 months; P=0.026) (Figure 3B).

Table 2

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Age >17.4 years | 0.911 | 0.951 (0.395–2.290) | |||

| Males | 0.331 | 0.580 (0.194–1.739) | |||

| Stage III–IV | 0.212 | 2.180 (0.641–7.411) | |||

| ECOG 2–3 | 0.093 | 2.432 (0.863–6.856) | |||

| aaIPI 2–3 | 0.011* | 3.057 (1.292–7.234) | 0.014* | 2.974 (1.249–7.083) | |

| Ferritin > UNL | 0.446 | 1.576 (0.463–5.360) | |||

| LDH > UNL | 0.179 | 1.799 (0.763–4.239) | |||

| CRP > UNL | 0.153 | 2.008 (0.772–5.223) | |||

| SUVmax >13.8 | 0.012* | 3.062 (1.279–7.335) | |||

| TMTV >101.4 mL | 0.020* | 2.800 (1.172–6.689) | 0.026* | 2.726 (1.126–6.599) | |

| TLG >333.6 | 0.187 | 1.791 (0.754–4.256) | |||

*, P<0.05. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; aaIPI, age-adjusted International Prognostic Index; UNL, upper normal limit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume; TLG, total lesion glycolysis.

Regarding OS, statistically significant features in the univariate analysis included ECOG 2–3, SUVmax >13.8, TMTV >101.4 mL, and TLG >333.6. After performing multivariate analysis, we found that ECOG 2–3 and TMTV >101.4 mL had an independent correlation with OS (Table 3). The median OS in the ECOG 0–1 group was significantly greater than that of the ECOG 2–3 group (NR vs. 9.7 months; P=0.015) (Figure 4A). Similarly, the median OS was significantly longer in the TMTV ≤101.4 mL group than in the TMTV >101.4 mL group (NR vs. 10.9 months; P=0.011) (Figure 4B).

Table 3

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Age >17.4 years | 0.633 | 1.288 (0.456–3.642) | |||

| Males | 0.694 | 0.773 (0.214–2.792) | |||

| Stage III–IV | 0.349 | 2.038 (0.459–9.055) | |||

| ECOG 2–3 | 0.015* | 3.970 (1.314–11.993) | 0.015* | 4.009 (1.315–12.222) | |

| aaIPI 2–3 | 0.177 | 2.016 (0.729–5.572) | |||

| Ferritin > UNL | 0.141 | 4.635 (0.603–35.641) | |||

| LDH > UNL | 0.261 | 1.793 (0.647–4.967) | |||

| CRP > UNL | 0.056 | 2.933 (0.973–8.845) | |||

| SUVmax >13.8 | 0.035* | 3.066 (1.084–8.667) | |||

| TMTV >101.4 mL | 0.011* | 3.966 (1.371–11.471) | 0.011* | 4.023 (1.372–11.796) | |

| TLG >333.6 | 0.047* | 2.296 (1.016–8.674) | |||

*, P<0.05. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; aaIPI, age-adjusted International Prognostic Index; UNL, upper normal limit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume; TLG, total lesion glycolysis.

Significant pairwise correlations emerged among aaIPI, ECOG, TMTV, SUVmax, and TLG. The specific correlations were as follows: for aaIPI and ECOG, ρ=0.476 and P<0.001; for aaIPI and SUVmax, ρ=0.473 and P=0.003; for aaIPI and TMTV, ρ=0.372 and P=0.012; for aaIPI and TLG, ρ=0.486 and P<0.001; for ECOG and SUVmax, ρ=0.422 and P=0.004; for ECOG and TMTV, ρ=0.412 and P=0.005; for ECOG and TLG, ρ=0.488 and P<0.001; for SUVmax and TMTV, ρ=0.646 and P<0.001; for SUVmax and TLG, ρ=0.803 and P<0.001; and finally, for TMTV and TLG, ρ=0.933 and P<0.001.

Prediction of toxicity

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that a pretreatment LDH > upper normal limit (UNL) and TMTV >101.4 mL were significantly associated with the emergence of grade 2–4 CRS. Meanwhile, a pretreatment CRP > UNL was an independent indicator for the occurrence of ICANS grade 2–4 (Table 4).

Table 4

| Variable | CRS grade 2–4 | ICANS grade 2–4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Puni | Pmulti | OR (95% CI) | Puni | Pmulti | ||

| Ferritin > UNL | 4.773 (0.531–42.888) | 0.163 | 4.750 (0.507–44.483) | 0.172 | |||

| LDH > UNL | 6.389 (1.651–24.728) | 0.007* | 0.030* | 2.000 (1.651–24.728) | 0.433 | ||

| CRP > UNL | 6.741 (1.430–31.773) | 0.016 | 11.000 (1.633–74.083) | 0.014* | 0.014* | ||

| SUVmax >13.8 | 1.478 (0.423–5.157) | 0.540 | 4.000 (0.646–24.768) | 0.136 | |||

| TMTV >101.4 mL | 6.171 (1.553–24.527) | 0.01* | 0.042* | 2.545 (0.444–14.585) | 0.294 | ||

| TLG >333.6 | 3.704 (1.028–13.346) | 0.045 | 3.200 (0.521–19.668) | 0.209 | |||

*, P<0.05. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; 18F-FDG PET/CT, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography; UNL, upper normal limit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume; TLG, total lesion glycolysis; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome; uni, univariate; multi, multivariate.

Discussion

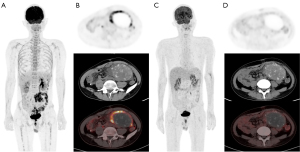

BL, DLBCL, and PMBCL are common malignancies in children and young adults (1). Studies have confirmed the value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in diagnosis, staging, efficacy assessment, and follow-up for this group of patients (24,25). However, there is scant literature regarding the prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoma treated with CAR T cells. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed 18F-FDG PET/CT features before CAR T-cell infusion in this patient population. We found that TMTV was significantly associated with PFS, OS, and grade 2–4 CRS. Furthermore, we analyzed the prognostic role of the clinical and laboratory indicators before CAR T therapy. aaIPI was associated with PFS, and ECOG score was associated with OS.

As a metabolic parameter of PET/CT, TMTV can reflect the systematic tumor burden and has already been confirmed to be one of the best prognostic indicators for patients with LBCL. Marchal et al. demonstrated that TMTV, at a cutoff value of 36 mL, serves as an independent predictor for PFS in patients with LBCL receiving CAR T-cell therapy (14). Dean et al. included 96 patients with LBCL who received anti-CD19 CAR T cells and found that the low-MTV group (cutoff value of 147.5 mL) had a better PFS and OS than did the high-MTV group (23). Other studies reported that TMTV was associated with prognosis in patients with LBCL treated with CAR T cells (26-31). In our study, the patients with low and high TMTV had different PFS and OS, as demonstrated in Figures 5,6, respectively. Although the conclusions were consistent, the cutoff values of the TMTV varied considerably, from 25 to 147.5 mL. Our study calculated the optimal threshold to be 101.4 mL, which was within the published range. However, the cutoff value of TMTV in our study was higher than that in most studies (14,26,31). The possible reasons are as follows: first, there were different time intervals between PET examinations and CAR T-cell infusion; second, there were differences in the study populations. Some studies also concluded that SUVmax and TLG of pretreatment PET/CT had prognostic value in patients with LBCL (15,29). Cohen et al. reported that an SUVmax >17.1 at the time of decision and SUVmax >12.1 at the time of transfusion were associated with shorter OS (15). Ababneh et al. found that high TLG was an independent prognostic factor for inferior PFS (29). In our study, univariate analysis indicated that higher SUVmax and TMTV were associated with worse PFS, whereas higher SUVmax, TLG, and TMTV were associated with poorer OS. However, in multivariate analysis, only TMTV was identified as an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS, while SUVmax and TLG were not predictive of PFS or OS. This might be due to the moderate-to-strong correlation among these three factors (ρ=0.646–0.933), which might have obscured the independent prognostic values of SUVmax and TLG in multivariate analyses (32). Our study also found that aaIPI was a prognostic indicator for PFS, while ECOG score was a prognostic indicator for OS, which is in line with the literature (5,15,33).

Treatment-related adverse effects also should be examined, as they can occasionally be fatal. Our study showed that higher TMTV was significantly associated with grade 2–4 CRS, but there was no significant association between the metabolic indicators and ICANS. Other studies have examined the relationship between PET/CT parameters and toxicity. Wang et al. found that higher MTV and TLG were associated with more severe CRS (34), and Hong et al. reported a similar result (35). In 38 patients treated with CAR T cells for LBCL, Gui et al. found that SUVmax was correlated with the severity of CRS (16). Meanwhile, Ababneh et al. concluded that high TLG was correlated with CRS and that high TMTV and SUVmax were correlated with ICANS (29). Our study also found that elevated LDH was associated with CRS and that elevated CRP was an independent prognostic factor for grade 2–4 ICANS, which is consistent with previous results (36,37). Our study did not find there to be an association between any of the PET variables and ICANS, possibly because of the small number of high-grade ICANS cases (6/45, 13.3%). A few studies have examined the relationship between metabolic parameters, clinical-laboratory characteristics, and toxicity, with the results being controversial, so the exact prognostic value of these parameters remains unclear. Recently, a study demonstrated that the occurrence of ICANS is associated with microglia activation and could be detected by translocator protein (TSPO) PET imaging (38), which might be a useful tool for the evaluation of ICANS.

This study involved several limitations which should be addressed. First, we employed a retrospective design, and selection bias was unavoidable. Therefore, prospective and large-sample studies are necessary. Second, the number of patients was limited while the pathology was relatively complex. Therefore, in the future, the relationship between PET/CT metabolic parameters and the prognosis of different types of LBCL should be analyzed in large-sample studies. Third, we only focused on the prognostic value of PET/CT before CAR T treatment. In our future studies, PET scans at different times and the inclusion of addition metabolic parameters should be adopted to enhance the value of PET/CT for patients undergoing CAR T therapy.

Conclusions

18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters have significant value for predicting prognosis and treatment-related adverse events for children and young adults with LBCL. TMTV was demonstrated to be predictive of PFS, OS, and severe CRS. aaIPI, a clinical indicator, was associated with PFS, while ECOG score was associated with OS. Furthermore, patients with higher LDH and CRP tended to have a greater severity of CRS and ICANS, respectively. Studies with larger samples should be performed to validate these results; nonetheless, we believe that the value of 18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters for prognosis and toxicity can be generalized and used for managing children and young adults with LBCL.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Nuclear Medicine of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Beijing GoBroad Boren Hospital, and Beijing Fengtai You’anmen Hospital for their assistance in carrying out this study.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1737/rc

Funding: This study was supported by grants from

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1737/coif). All authors report that this study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82272034) and the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. 7232031). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Friendship Hospital of Capital Medical University (No. 2024-P2-259-01) and followed the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The other participating hospital was informed and agreed with the study. The requirement of individual consent for this retrospective and observational analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Hochberg J, El-Mallawany NK, Abla O. Adolescent and young adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2016;173:637-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cairo M, Auperin A, Perkins SL, Pinkerton R, Harrison L, Goldman S, Patte C. Overall survival of children and adolescents with mature B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who had refractory or relapsed disease during or after treatment with FAB/LMB 96: A report from the FAB/LMB 96 study group. Br J Haematol 2018;182:859-69.

- Bluhm EC, Ronckers C, Hayashi RJ, Neglia JP, Mertens AC, Stovall M, Meadows AT, Mitby PA, Whitton JA, Hammond S, Barker JD, Donaldson SS, Robison LL, Inskip PD. Cause-specific mortality and second cancer incidence after non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Blood 2008;111:4014-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ehrhardt MJ, Mulrooney DA, Li C, Baassiri MJ, Bjornard K, Sandlund JT, Brinkman TM, Huang IC, Srivastava DK, Ness KK, Robison LL, Hudson MM, Krull KR. Neurocognitive, psychosocial, and quality-of-life outcomes in adult survivors of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 2018;124:417-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwon M, Iacoboni G, Reguera JL, Corral LL, Morales RH, Ortiz-Maldonado V, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel compared to tisagenlecleucel for the treatment of aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2023;108:110-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shalabi H, Qin H, Su A, Yates B, Wolters PL, Steinberg SM, et al. CD19/22 CAR T cells in children and young adults with B-ALL: phase 1 results and development of a novel bicistronic CAR. Blood 2022;140:451-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karsten H, Matrisch L, Cichutek S, Fiedler W, Alsdorf W, Block A. Broadening the horizon: potential applications of CAR-T cells beyond current indications. Front Immunol 2023;14:1285406. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Perales MA, Kersten MJ, Oluwole OO, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2022;386:640-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason J, Johnston PB, Glass B, Bachanova V, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2022;399:2294-308. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayden PJ, Roddie C, Bader P, Basak GW, Bonig H, Bonini C, et al. Management of adults and children receiving CAR T-cell therapy: 2021 best practice recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE) and the European Haematology Association (EHA). Ann Oncol 2022;33:259-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, Meignan M, Hutchings M, Müeller SP, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Fisher RI, Trotman J, Hoekstra OS, Hicks RJ, O'Doherty MJ, Hustinx R, Biggi A, Cheson BD. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3048-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geng H, Lian K, Zhang W. Prognostic value of (18)F-FDG PET/CT tumor metabolic parameters and Ki-67 in pre-treatment diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2024;14:325-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang W, Chao F, Li L, Gao Y, Qiu Y, Wang W, Gao J, Han X, Kang L. Predictive value of clinical characteristics and baseline (18)F-FDG PET/CT quantization parameters in primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a preliminary study. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023;13:8571-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marchal E, Palard-Novello X, Lhomme F, Meyer ME, Manson G, Devillers A, Marolleau JP, Houot R, Girard A. Baseline [18F]FDG PET features are associated with survival and toxicity in patients treated with CAR T cells for large B cell lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2024;51:481-9.

- Cohen D, Luttwak E, Beyar-Katz O, Hazut Krauthammer S, Bar-On Y, Amit O, Gold R, Perry C, Avivi I, Ram R, Even-Sapir E. [18F]FDG PET-CT in patients with DLBCL treated with CAR-T cell therapy: a practical approach of reporting pre- and post-treatment studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2022;49:953-62.

- Gui J, Li M, Xu J, Zhang X, Mei H, Lan X. [18F]FDG PET/CT for prognosis and toxicity prediction of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2024;51:2308-19.

- Pan J, Yang JF, Deng BP, Zhao XJ, Zhang X, Lin YH, Wu YN, Deng ZL, Zhang YL, Liu SH, Wu T, Lu PH, Lu DP, Chang AH, Tong CR. High efficacy and safety of low-dose CD19-directed CAR-T cell therapy in 51 refractory or relapsed B acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Leukemia 2017;31:2587-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Deng B, Yin Z, Lin Y, An L, Liu D, Pan J, Yu X, Chen B, Wu T, Chang AH, Tong C. Combination of CD19 and CD22 CAR-T cell therapy in relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia after allogeneic transplantation. Am J Hematol 2021;96:671-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCarten KM, Nadel HR, Shulkin BL, Cho SY. Imaging for diagnosis, staging and response assessment of Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr Radiol 2019;49:1545-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nioche C, Orlhac F, Boughdad S, Reuzé S, Goya-Outi J, Robert C, Pellot-Barakat C, Soussan M, Frouin F, Buvat I. LIFEx: A Freeware for Radiomic Feature Calculation in Multimodality Imaging to Accelerate Advances in the Characterization of Tumor Heterogeneity. Cancer Res 2018;78:4786-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJ, Giammarile F, Tatsch K, Eschner W, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015;42:328-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, Somerville RP, Carpenter RO, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:540-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dean EA, Mhaskar RS, Lu H, Mousa MS, Krivenko GS, Lazaryan A, Bachmeier CA, Chavez JC, Nishihori T, Davila ML, Khimani F, Liu HD, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Shah BD, Jain MD, Balagurunathan Y, Locke FL. High metabolic tumor volume is associated with decreased efficacy of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2020;4:3268-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Badr S, Kotb M, Elahmadawy MA, Moustafa H. Predictive Value of FDG PET/CT Versus Bone Marrow Biopsy in Pediatric Lymphoma. Clin Nucl Med 2018;43:e428-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng G, Servaes S, Alavi A, Zhuang H. FDG PET and PET/CT in the Management of Pediatric Lymphoma Patients. PET Clin 2008;3:621-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galtier J, Vercellino L, Chartier L, Olivier P, Tabouret-Viaud C, Mesguich C, Di Blasi R, Durand A, Raffy L, Gros FX, Madelaine I, Meignin V, Mebarki M, Rubio MT, Feugier P, Casasnovas O, Meignan M, Thieblemont C. Positron emission tomography-imaging assessment for guiding strategy in patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma receiving CAR T cells. Haematologica 2023;108:171-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vercellino L, Di Blasi R, Kanoun S, Tessoulin B, Rossi C, D'Aveni-Piney M, et al. Predictive factors of early progression after CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2020;4:5607-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah NN, Nagle SJ, Torigian DA, Farwell MD, Hwang WT, Frey N, Nasta SD, Landsburg D, Mato A, June CH, Schuster SJ, Porter DL, Svoboda J. Early positron emission tomography/computed tomography as a predictor of response after CTL019 chimeric antigen receptor -T-cell therapy in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Cytotherapy 2018;20:1415-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ababneh HS, Ng AK, Abramson JS, Soumerai JD, Takvorian RW, Frigault MJ, Patel CG. Metabolic parameters predict survival and toxicity in chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy-treated relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol 2024;42:e3231. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Georgi TW, Kurch L, Franke GN, Jentzsch M, Schwind S, Perez-Fernandez C, Petermann N, Merz M, Metzeler K, Borte G, Hoffmann S, Herling M, Denecke T, Kluge R, Sabri O, Platzbecker U, Vučinić V. Prognostic value of baseline and early response FDG-PET/CT in patients with refractory and relapsed aggressive B-cell lymphoma undergoing CAR-T cell therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023;149:6131-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iacoboni G, Simó M, Villacampa G, Catalá E, Carpio C, Díaz-Lagares C, Vidal-Jordana Á, Bobillo S, Marín-Niebla A, Pérez A, Jiménez M, Abrisqueta P, Bosch F, Barba P. Prognostic impact of total metabolic tumor volume in large B-cell lymphoma patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy. Ann Hematol 2021;100:2303-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth Analg 2018;126:1763-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burggraaff CN, Eertink JJ, Lugtenburg PJ, Hoekstra OS, Arens AIJ, de Keizer B, Heymans MW, van der Holt B, Wiegers SE, Pieplenbosch S, Boellaard R, de Vet HCW, Zijlstra JMHOVON Imaging Working Group and the HOVON Lymphoma Working Group. 18F-FDG PET Improves Baseline Clinical Predictors of Response in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The HOVON-84 Study. J Nucl Med 2022;63:1001-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Hu Y, Yang S, Wei G, Zhao X, Wu W, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Chen D, Wu Z, Xiao L, Chang AH, Huang H, Zhao K. Role of Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in Predicting the Adverse Effects of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy in Patients with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019;25:1092-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong R, Tan Su Yin E, Wang L, Zhao X, Zhou L, Wang G, Zhang M, Zhao H, Wei G, Wang Y, Wu W, Zhang Y, Ni F, Hu Y, Huang H, Zhao K. Tumor Burden Measured by 18F-FDG PET/CT in Predicting Efficacy and Adverse Effects of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Front Oncol 2021;11:713577. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gauthier J, Gazeau N, Hirayama AV, Hill JA, Wu V, Cearley A, et al. Impact of CD19 CAR T-cell product type on outcomes in relapsed or refractory aggressive B-NHL. Blood 2022;139:3722-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenbaum U, Strati P, Saliba RM, Torres J, Rondon G, Nieto Y, et al. CRP and ferritin in addition to the EASIX score predict CAR-T-related toxicity. Blood Adv 2021;5:2799-806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vinnakota JM, Biavasco F, Schwabenland M, Chhatbar C, Adams RC, Erny D, et al. Targeting TGFβ-activated kinase-1 activation in microglia reduces CAR T immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Nat Cancer 2024;5:1227-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]