Altered hypothalamus functional connectivity and psychological stress in patients with alopecia areata

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune inflammatory disease with a complex etiology characterized by nonscarring hair loss (1). The prevalence of AA ranges from 0.1% to 0.2%, and the lifetime risk is 2% (2). Patients with AA are particularly susceptible to comorbid autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), psoriasis, and idiopathic dermatitis, as well as psychiatric disorders, such as depression (3-5). It is currently believed that the significant impact of hair loss on the appearance of patients with AA leads to social burdens and mental disorders, resulting in noticeable psychological stress (6). Clinical experience indicates that onset of AA is highly related to psychological stress, with patients sometimes experiencing sudden, overnight hair loss following severe psychological trauma (7). Therefore, it is essential to investigate how psychological changes impact AA. Moreover, AA comorbidities can lead to social and occupational impairments, sleep disorders, and even suicidal tendencies; thus, clarifying the potential mechanisms underlying these comorbidities may have clinical ramifications (8). Although the precise reasons for this increased susceptibility remains unknown (9), multiple studies have indicated that AA and its comorbidities share certain characteristics such as psychological stress and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis leading to inflammation and abnormal immune activity (10-13). This suggests that psychological and neurological changes might be the underlying mechanisms for AA comorbidities. As the hypothalamus is the center of the HPA axis and an important site of psychological stress (14), it is reasonable to speculate that the hypothalamus plays a central role in the pathogenesis of AA and its comorbidities. We hypothesized that patients with AA exhibit abnormal activity in the hypothalamus that is associated with psychological stress.

To our knowledge, no study has been conducted on brain activity changes in patients with AA. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) is a noninvasive imaging technique used to detect abnormal spontaneous neural activity through blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals (15). The amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) is a data-driven method in rs-fMRI that examines regional spontaneous brain activity by assessing the strength of the BOLD signal in low-frequency oscillations within localized brain areas. Seed-based analysis correlates the BOLD fMRI time series of a defined region of interest (ROI) against all other regions, resulting in a functional connectivity (FC) map (16). Alterations in ALFF and FC may represent potentially abnormal brain activity and have become reliable neuroimaging markers for examining brain activity in various diseases (17,18), including some comorbidities of AA (19-21). For example, one study found that differences in resting-state FC (RSFC) in healthy children with a familial risk for depression could serve as a potential neuromarker for predicting the onset of major depressive disorder (MDD) (22). Another study used RSFC to differentiate patients with non-neuropsychiatric SLE (non-NP-SLE) from healthy controls (HCs) (23). However, our study is the first to use MRI to assess altered hypothalamic activity in patients with AA, which may be a potential neuromarker of psychological stress in these patients. Our findings may will help us to further understand the mechanisms underlying the relationship between psychological stress and AA and may provide valuable insights for the improved diagnosis and treatment of AA. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1684/rc).

Methods

Participants

Consecutive adult patients with clinically confirmed AA, but not those with any comorbidity such as SLE, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and depression, were enrolled from dermatology clinics from December 2021 to December 2023. HCs were selected to match the patients in terms of age and gender and were recruited from the community via local newspaper advertisements and referrals from patients and their families. This cross-sectional study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital (No. 202211746), and all participants signed an informed consent form.

Clinical evaluation and data collection

Data on demographics, clinical features, laboratory results, treatments, and outcomes were obtained from medical records through standardized data collection forms. Patients were newly diagnosed based on clinical and pathological information and had not received any systemic treatment. All patients were assessed with the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score (24) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (25). Blood samples were also collected for AA-related immune markers, including total serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels.

Neuropsychological testing

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) score (26) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score (27) were used for neuropsychological testing. All interviews and assessments were conducted on the same day as the brain MRI scans.

rs-fMRI data acquisition and preprocessing

All rs-fMRI scans were conducted using a the MAGNETOM Prisma 3T MRI scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). A high-resolution, three-dimensional T1-weighted structural image was acquired under the following parameters: repetition time =2,300 ms, echo time =3.2 ms, field of view (FOV) =256×256 mm, and slice thickness =1.0 mm. The rs-fMRI data were then collected using an echo-planar imaging sequence under the following parameters: repetition time =2,000 ms, slice thickness =2 mm, number of slices =75, echo time =34 ms, FOV =220×220 mm, in-plane resolution =128×128, slice gap =0 mm, and flip angle =66°. Participants were instructed to keep their eyes closed during the scan.

Preprocessing of rs-fMRI images was carried out using Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM 12; https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/) and DPARSFA5.3 (http://rfmri.org/DPARSF) (28). To eliminate the effects of participant discomfort and magnetic field inhomogeneity, the first 10 time points were excluded, while the remaining 230 time points were included in the analysis. Image preprocessing involved correction for time and head motion, with data being excluded from analysis if the head motion exceeded 2 mm or 2°. DPARSF was used to calculate the mean head movement parameters and mean head position displacement (volume-level mean frame-wise displacement), and the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Scanned functional images were aligned to a standard template with voxel resampling of 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm. Spatial smoothing was performed using a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm × 6 mm × 6 mm. Data were temporal band-pass filtered (0.01–0.10 Hz) to decrease low-frequency drift and physiological high-frequency noise, the linear tendency was removed, and head movement parameters were regressed out.

ALFF analysis

ALFF analysis was performed using DPARSF 5.3 software. The filtered time series were converted into the frequency domain using fast Fourier transform (FFT). The power spectrum was obtained through square-based FFT, and the mean within the 0.01- to 0.10-Hz frequency range was calculated for each voxel. This mean value, expressed as the square root, was used as the ALFF measurement. A mask was generated using the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template. The data were normalized across participants by dividing the overall average ALFF by the ALFF of each individual voxel. The z-score ALFF graph of the normal distribution was obtained by calculating the ALFF index and normalizing it by subtracting the mean from the standard deviation.

FC analysis

FC analyses were performed using the seed-based method with the hypothalamus serving as a seed point in a high-resolution probabilistic in vivo atlas of human subcortical nuclei (29). Pearson correlation analyses were then performed between timeseries of all seeds, and voxels of the whole brain correlation coefficients (r values) were converted into Fisher z-values for the measurement of FC.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were analyzed using independent two-sample t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests, while Chi-squared tests were applied to categorical variables. For the ALFF and FC analyses, two-sample t-tests were used to identify differences between the two groups. Gaussian random field (GRF) correction was applied to results to a voxel level threshold of <0.001, and automatic estimation of the effective smoothing kernel was conducted to obtain a corresponding cluster level, with P<0.05 being considered statistically significant. Correlation analysis between altered hypothalamus activity and clinical data, including neuropsychological tests, the DLQI, and blood samples, was conducted using Pearson correlation or Spearman rank correlation. The two-tailed statistical significance was set at P<0.05. All analyses included age and gender as covariates.

Results

Participant information and clinical assessment

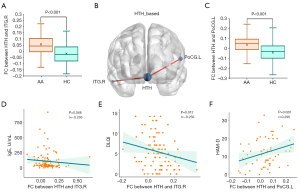

A total of 102 patients with AA and 84 matched HCs were enrolled. Their demographic information is presented in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between patients with AA and HCs in terms of age or gender (all P values >0.05). Significant differences were found between patients with AA and HCs in depression and anxiety as assessed by HAM-D score and HAM-A score, respectively (all P values <0.05) (Figure S1). The SALT score of patients with AA was correlated with disease duration (r=0.347; P<0.001), the age of onset (r=−0.266; P=0.007), and DLQI (r=0.296; P=0.003). DLQI was positively correlated with HAM-D score (r=0.424; P=0.001), HAM-A score (r=0.277; P=0.033), and disease duration (r=0.215; P=0.031) (Table 2 and Figure 1). However, there was no correlation between SALT score and HAM-A score, HAM-D score, and total serum IgE in patients with AA (all P values >0.05).

Table 1

| Characteristics | AA (n=102) | HC (n=84) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.70 | ||

| Male | 42 (41.2) | 33 (39.3) | |

| Female | 60 (58.8) | 51 (60.7) | |

| Age (years) | 33 [21.75–43] | 26.5 [24–50] | 0.94 |

| Age of onset (years) | 29.91 [18.25–42.77] | – | – |

| Disease duration (years) | 1 (0.25–3.19) | – | – |

| SALT score | 36 [15–70] | – | – |

| Mild SALT [0–24] | 40 (39.2) | – | – |

| Moderate SALT [25–49] | 24 (23.5) | – | – |

| Severe SALT [≥50] | 38 (37.3) | – | – |

| Questionnaires | – | – | |

| DLQI | 5 [2–9] | – | – |

| HAM-A | 12.03 (±7.38) | 8.29 (±2.76) | <0.001*** |

| HAM-D | 12.15 (±7.97) | 7.98 (±2.55) | <0.001*** |

| Total serum IgE (U/mL) | 48.65 [30.20–142.25] | – | – |

| ALFF | −0.187 (±0.128) | −0.917 (±0.111) | <0.001*** |

Data are presented as n (%), median [IQR], or mean (±SD). ***, P<0.001. AA, alopecia areata; ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HC, healthy control; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IQR, interquartile range; SALT, Severity of Alopecia Tool; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2

| Characteristics | r value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset | Disease duration | DLQI | HAM-A | HAM-D | SALT score | ALFF values | |

| Age of onset | – | – | – | – | – | −0.266** | 0.337** |

| Disease duration | – | – | 0.215* | – | – | 0.347*** | – |

| DLQI | – | 0.215* | 0.277* | 0.424** | 0.296** | – | |

| HAM-A | – | – | 0.277* | – | – | – | – |

| HAM-D | – | – | 0.424** | – | – | – | – |

| SALT score | −0.266** | 0.347*** | 0.296** | – | – | – | −0.211* |

| ALFF | 0.337** | – | – | – | – | −0.211* | |

*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. AA, alopecia areata; ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; SALT, Severity of Alopecia Tool.

ALFF alterations

The altered ALFF in the hypothalamus showed a statistically significant difference between patients with AA and HCs (P<0.05) (Table 1 and Figure S1). There was a significant correlation between ALFF values and both SALT score (r=−0.211; P=0.033) and the age of onset (r=0.337; P=0.001) (Table 2 and Figure 1). However, there was no significant correlation between ALFF values and neuropsychological tests or total serum IgE (all P values >0.05).

Alterations in FC

Compared to HCs, patients with AA showed increased FC between the hypothalamus and both the left precentral gyrus and the right inferior temporal gyrus (GRF-corrected: voxel P<0.001 and cluster P<0.05) (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 3

| Seed | Brain region | MNI peak coordinates | t value | Cluster size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Hypothalamus | The left postcentral gyrus | −48 | −15 | 30 | 4.0701 | 20 |

| The right inferior temporal gyrus | 60 | −36 | −21 | 4.1824 | 9 | |

AA, alopecia areata; GRF, Gaussian random field; HC, healthy control; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute template.

For patients with AA, there increased FC between the hypothalamus and left precentral gyrus was positively correlated with HAM-D score (r=0.296; P=0.020), while increased FC between the hypothalamus and the right inferior temporal gyrus was negatively correlated with both DLQI (r=−0.256; P=0.012) and total serum IgE (r=−0.203; P=0.048) (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this study, we used the hypothalamus as an ROI to assess the alterations in hypothalamic ALFF and whole-brain FC in patients with AA and to determine its relationship with psychological stress. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess brain functional changes and their relationship with psychological stress in patients with AA.

Our study showed that compared to HCs, AA patients demonstrated heightened psychological tension, with a significantly higher HAM-D score and HAM-A score (P<0.05). Additionally, the duration and severity of AA were found to impact patients’ quality of life, which in turn further elevated their level of psychological stress. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which suggest that hair loss in patients AA has a notable impact on appearance, contributing to social burden and stigma and thereby increasing psychological stress (30-32). Clinically, AA onset is observed to be highly susceptible to psychological influences. For example, patients experiencing significant psychological trauma have been reported to develop sudden, severe hair loss, commonly referred to as “overnight baldness” (33). The latest expert consensus indicates a disease duration of 12 months or longer, impaired quality of life due to AA, and a history of anxiety, depression, or suicidality as independent risk factors for worsening AA severity and a higher SALT score (34). Although psychological stress is closely linked to both the onset and progression of AA, the causal relationship and underlying mechanisms remain to be further explored.

Our study showed that there were statistical differences in hypothalamic ALFF changes between patients with AA and HCs. Furthermore, ALFF changes in patients with AA were correlated with age of onset (P=0.001; r=0.337) and SALT score (P=0.033; r=−0.211). These results indicate that altered hypothalamic activity in patients with AA is associated with the clinical features of AA. Current mainstream theory suggests that AA is an immunological skin disease that disrupts immune privilege (IP) in hair follicles as mediated by CD8+ cells (9,35). Many studies have reported that HPA axis dysregulation is closely related to the pathogenesis of AA. This dysregulation leads to the abnormal secretion of stress hormones and neuropeptides, such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), glucocorticoids (GC), and substance P (SP), resulting in immune abnormalities and inflammatory activity (36,37). As the hypothalamus is a central component of the HPA axis, the abnormal ALFF in the hypothalamus of patients with AA in our study is not surprising. This abnormal ALFF might be a potential mechanism underlying AA onset. Additionally, the age of onset and SALT scores are closely related to AA prognosis (38,39). Thus, we speculate that changes in hypothalamic ALFF could serve as a potential neuroimaging marker for AA prognosis. In addition, some research suggests that comorbidities of AA also include dysregulation of the HPA axis and FC or structural abnormalities in the hypothalamus. For example, on study found that MDD was characterized by neuroendocrine dysregulation and hyperactivity of the HPA axis, primarily manifesting as a reduction in hypothalamic RSFC (40). In another study, the intensity of hypothalamic RSFC was significantly associated with the improvement of depressive symptoms following 4 weeks of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (41). Furthermore, some research has indicated a negative correlation between hypothalamic gray-matter density and perceived stress in patients with atopic dermatitis (42). In summary, altered hypothalamic activity may be the underlying neural basis of AA and its comorbidities.

We also found increased FC between the hypothalamus and left postcentral gyrus and right inferior temporal gyrus in patients with AA. Increased FC between the hypothalamus and left postcentral gyrus was positively correlated with HAM-D score (r=0.296; P=0.02), while increased FC between the hypothalamus and the right inferior temporal gyrus was negatively correlated with both DLQI (r=−0.202; P=0.043) and total serum IgE (r=−0.236; P=0.040). Studies have shown that patients with AA often exhibit elevated levels of IgE (43), which are associated with various cytokines (44). Therefore, elevated IgE levels may indicate abnormal immune activity in patients with AA (45). The hypothalamus is known to be an important node in the salience network (SN) and the limbic network (46), regulating physiological and psychological functions such as neuroendocrine, metabolic, and emotional processes through communication with other brain regions and peripheral target tissues (47). The postcentral gyrus, integral to the frontoparietal network (FPN), regulates emotional processing stages, including emotional state generation and regulation (48). The inferior temporal gyrus is also one of the nodes of the brain’s default mode network (DMN), which is involved in higher cognitive functions and emotion regulation (49). Our study indicated that changes in connectivity between the hypothalamus and these brain regions may reflect integration abnormalities in the SN, DMN, and FPN in patients with AA under psychological stress and may be related to immune abnormalities. Several studies have shown that psychological stress in the comorbidities of AA is associated with dynamic changes within and between the SN, DMN, and FPN (50,51). A resting-state study of SLE revealed that patients with SLE exhibited altered brain connectivity in several networks. Within the DMN, there was increased RSFC in the right cingulate cortex and decreased RSFC in the left precuneus. In the SN, there was increased RSFC in the left insular cortex and decreased RSFC in the right anterior cingulate cortex. Additionally, in the FPN, there was decreased RSFC in the right middle frontal gyrus. Furthermore, abnormal RSFC of the precuneus and insula in the DMN and SN were associated with psychiatric symptoms in SLE (52). A study of resting-state brain function in 222 patients with psoriasis showed altered connectivity in key brain regions of the DMN-prefrontal circuit in the patients with psoriasis (53). Meanwhile, a study on MDD reported reduced hypothalamic connectivity with the corresponding subcortical structures in patients with depression. Moreover, cortisol secretion was associated with increased HAM-D score in these patients (54).

In conclusion, our study indicates that functional changes in the hypothalamus may be a potential neural mechanism for the onset of AA. Additionally, alterations in the connectivity of HPA axis-related brain regions may serve as neuroimaging markers of psychological stress in patients with AA. The dynamic changes in the hypothalamus’s brain network connectivity might be a common underlying neural basis for AA and its comorbidities. In addition, considering that the pathogenesis of AA is closely related to psychological stress, we believe future research should focus on the structural and functional changes in brain regions associated with stress, such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus, and their relationship to the development of AA.

There are several limitations to this study which should be addressed. To begin, the case selection bias could not be avoided, as patients with more severe AA might visit Xiangya Hospital for further treatment, given that it is a major tertiary medical center in the mid-south region of China. Moreover, we did not collect IgE blood samples from the HCs. During HC recruitment, we excluded participants with conditions potentially associated with elevated IgE levels. Additionally, some HCs declined blood sampling, which limited our ability to obtain IgE data for this group. In future studies, we aim to address this limitation by actively recruiting HC participants willing to provide blood samples. Additionally, the cross-sectional design did not allow for the assessment of the temporal dynamics of detected functional abnormalities. We did not assess changes in brain function activity in patients with AA before and after treatment. Future longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes are required to validate our findings and investigate whether connectivity changes are reversible following remission. Finally, subgroup analyses of patients with AA were not performed due to the limited sample size and the heterogeneity of the subgroups. More in-depth and comprehensive analyses of the typology of AA and its inflammatory-immunological correlates in relation to psychological stress are needed.

Conclusions

This is the first brain imaging study of Chinese patients with AA.

Intrinsic brain activity and connectivity in HPA axis-related brain regions were altered in patients with AA. These changes can serve as potential neuroimaging biomarkers of psychological stress in patients with AA, providing new ideas for diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1684/rc

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1684/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital (No. 202211746). All participants signed an informed consent form.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gaurav A, Eang B, Mostaghimi A. Alopecia Areata. JAMA Dermatol 2024;160:372. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dainichi T, Iwata M, Kaku Y. Alopecia areata: What's new in the epidemiology, comorbidities, and pathogenesis? J Dermatol Sci 2023;112:120-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ly S, Manjaly P, Kamal K, Shields A, Wafae B, Afzal N, Drake L, Sanchez K, Gregoire S, Zhou G, Mita C, Mostaghimi A. Comorbid Conditions Associated with Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2023;24:875-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeon JJ, Jung SW, Kim YH, Parisi R, Lee JY, Kim MH, Lee WS, Lee S. Global, regional and national epidemiology of alopecia areata: a systematic review and modelling study. Br J Dermatol 2024;191:325-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Augustin M, Ben-Anaya N, Müller K, Hagenström K. Epidemiology of alopecia areata and population-wide comorbidities in Germany: analysis of longitudinal claims data. Br J Dermatol 2024;190:374-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schielein MC, Tizek L, Ziehfreund S, Sommer R, Biedermann T, Zink A. Stigmatization caused by hair loss - a systematic literature review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020;18:1357-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paus R. Exploring the "brain-skin connection": Leads and lessons from the hair follicle. Curr Res Transl Med 2016;64:207-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee S, Lee YB, Kim BJ, Bae S, Lee WS. All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Risks Associated With Alopecia Areata: A Korean Nationwide Population-Based Study. JAMA Dermatol 2019;155:922-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn D, Kim H, Lee B, Hahm DH. Psychological Stress-Induced Pathogenesis of Alopecia Areata: Autoimmune and Apoptotic Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:11711. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keller JJ. Cutaneous neuropeptides: the missing link between psychological stress and chronic inflammatory skin disease? Arch Dermatol Res 2023;315:1875-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Troubat R, Barone P, Leman S, Desmidt T, Cressant A, Atanasova B, Brizard B, El Hage W, Surget A, Belzung C, Camus V. Neuroinflammation and depression: A review. Eur J Neurosci 2021;53:151-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulos A, Chrousos GP. Stress-related skin disorders. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2016;17:295-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Han K, Huang Q, Hu W, Mo J, Wang J, Deng K, Zhang R, Tan X. Systemic lupus erythematosus-related brain abnormalities in the default mode network and the limbic system: A resting-state fMRI meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2024;355:190-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan KL, Poller WC, Swirski FK, Russo SJ. Central regulation of stress-evoked peripheral immune responses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2023;24:591-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Logothetis NK. What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature 2008;453:869-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lv H, Wang Z, Tong E, Williams LM, Zaharchuk G, Zeineh M, Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Ball TM, Liao C, Wintermark M. Resting-State Functional MRI: Everything That Nonexperts Have Always Wanted to Know. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018;39:1390-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Postuma RB. Resting state MRI: a new marker of prodromal neurodegeneration? Brain 2016;139:2106-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiong X, Dai L, Chen W, Lu J, Hu C, Zhao H, Ke J. Dynamics and concordance alterations of regional brain function indices in vestibular migraine: a resting-state fMRI study. J Headache Pain 2024;25:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee IS, Yoon DE, Lee S, Kang JH, Chae Y, Park HJ, Kim J. Neural Biomarkers for Identifying Atopic Dermatitis and Assessing Acupuncture Treatment Response Using Resting-State fMRI. J Asthma Allergy 2024;17:383-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou E, Wang W, Ma S, Xie X, Kang L, Xu S, Deng Z, Gong Q, Nie Z, Yao L, Bu L, Wang F, Liu Z. Prediction of anxious depression using multimodal neuroimaging and machine learning. Neuroimage 2024;285:120499. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Preziosa P, Rocca MA, Ramirez GA, Bozzolo EP, Canti V, Pagani E, Valsasina P, Moiola L, Rovere-Querini P, Manfredi AA, Filippi M. Structural and functional brain connectomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Neurol 2020;27:113-e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Gabrieli JDE, Shapero BG, Biederman J, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Chai XJ. Intrinsic Functional Brain Connectivity Predicts Onset of Major Depression Disorder in Adolescence: A Pilot Study. Brain Connect 2019;9:388-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li X, Zhang P, Zhou W, Li Y, Sun Z, Chen J, Xia J, Zou H. Altered degree centrality in patients with non-neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a resting-state fMRI study. J Investig Med 2022;70:1746-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wyrwich KW, Kitchen H, Knight S, Aldhouse NVJ, Macey J, Nunes FP, Dutronc Y, Mesinkovska N, Ko JM, King BA. The Alopecia Areata Investigator Global Assessment scale: a measure for evaluating clinically meaningful success in clinical trials. Br J Dermatol 2020;183:702-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qi S, Xu F, Sheng Y, Yang Q. Assessing quality of life in Alopecia areata patients in China. Psychol Health Med 2015;20:97-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan JQ, Lu WJ, Tan WQ, Liu X, Wang YT, Wang NB, Zhuang LX. Effectiveness of Acupuncture for Anxiety Among Patients With Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2232133. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Croarkin PE, Elmaadawi AZ, Aaronson ST, Schrodt GR Jr, Holbert RC, Verdoliva S, Heart KL, Demitrack MA, Strawn JR. Left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents: a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021;46:462-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan CG, Wang XD, Zuo XN, Zang YF. DPABI: Data Processing & Analysis for (Resting-State) Brain Imaging. Neuroinformatics 2016;14:339-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pauli WM, Nili AN, Tyszka JM. A high-resolution probabilistic in vivo atlas of human subcortical brain nuclei. Sci Data 2018;5:180063. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buontempo MG, Shapiro J, Lo Sicco K. Psychological Outcomes Among Patients With Alopecia Areata. JAMA Dermatol 2023;159:1013. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali NS, Tollefson MM, Lohse CM, Torgerson RR. Incidence and comorbidities of pediatric alopecia areata: A retrospective matched cohort study using the Rochester Epidemiology Project. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022;87:427-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vélez-Muñiz RDC, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Jurado-Santa Cruz F, Morales-Sánchez MA. Psychological Profile and Quality of Life of Patients with Alopecia Areata. Skin Appendage Disord 2019;5:293-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creadore A, Manjaly P, Li SJ, Tkachenko E, Zhou G, Joyce C, Huang KP, Mostaghimi A. Evaluation of Stigma Toward Individuals With Alopecia. JAMA Dermatol 2021;157:392-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moussa A, Bennett M, Wall D, Meah N, York K, et al. The Alopecia Areata Severity and Morbidity Index (ASAMI) Study: Results From a Global Expert Consensus Exercise on Determinants of Alopecia Areata Severity. JAMA Dermatol 2024;160:341-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simakou T, Butcher JP, Reid S, Henriquez FL. Alopecia areata: A multifactorial autoimmune condition. J Autoimmun 2019;98:74-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergler-Czop B, Miziołek B, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. Alopecia areata - hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is a myth? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:1555-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Yu M, Yu W, Weinberg J, Shapiro J, McElwee KJ. Development of alopecia areata is associated with higher central and peripheral hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal tone in the skin graft induced C3H/HeJ mouse model. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:1527-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, Brinster N, Christiano AM, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata: Disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:1-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guttman-Yassky E, Pavel AB, Diaz A, Zhang N, Del Duca E, Estrada Y, King B, Banerjee A, Banfield C, Cox LA, Dowty ME, Page K, Vincent MS, Zhang W, Zhu L, Peeva E. Ritlecitinib and brepocitinib demonstrate significant improvement in scalp alopecia areata biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022;149:1318-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang D, Xue SW, Tan Z, Wang Y, Lian Z, Sun Y. Altered hypothalamic functional connectivity patterns in major depressive disorder. Neuroreport 2019;30:1115-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tu Y, Fang J, Cao J, Wang Z, Park J, Jorgenson K, Lang C, Liu J, Zhang G, Zhao Y, Zhu B, Rong P, Kong J. A distinct biomarker of continuous transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation treatment in major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul 2018;11:501-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki H, Schut C, Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Nattkemper LA, Yosipovitch G. A Negative Association of Hypothalamic Volume and Perceived Stress in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 2020;100:adv00129. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, McElwee KJ. Allergy promotes alopecia areata in a subset of patients. Exp Dermatol 2020;29:239-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakry OA, El Shazly RM, Basha MA, Mostafa H. Total serum immunoglobulin E in patients with alopecia areata. Indian Dermatol Online J 2014;5:122-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zaaroura H, Gilding AJ, Sibbald C. Biomarkers in alopecia Areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev 2023;22:103339. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schimmelpfennig J, Topczewski J, Zajkowski W, Jankowiak-Siuda K. The role of the salience network in cognitive and affective deficits. Front Hum Neurosci 2023;17:1133367. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kullmann S, Veit R. Resting-state functional connectivity of the human hypothalamus. Handb Clin Neurol 2021;179:113-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kropf E, Syan SK, Minuzzi L, Frey BN. From anatomy to function: the role of the somatosensory cortex in emotional regulation. Braz J Psychiatry 2019;41:261-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin YH, Young IM, Conner AK, Glenn CA, Chakraborty AR, Nix CE, Bai MY, Dhanaraj V, Fonseka RD, Hormovas J, Tanglay O, Briggs RG, Sughrue ME. Anatomy and White Matter Connections of the Inferior Temporal Gyrus. World Neurosurg 2020;143:e656-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kühnel A, Czisch M, Sämann PG. BeCOME Working Group; Binder EB, Kroemer NB. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Stress-Induced Network Reconfigurations Reflect Negative Affectivity. Biol Psychiatry 2022;92:158-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Bo Q, Li F, Zhao L, Wang Y, Liu R, Chen X, Wang C, Zhou Y. Altered effective connectivity among core brain networks in patients with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2022;152:296-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonacchi R, Rocca MA, Ramirez GA, Bozzolo EP, Canti V, Preziosa P, Valsasina P, Riccitelli GC, Meani A, Moiola L, Rovere-Querini P, Manfredi AA, Filippi M. Resting state network functional connectivity abnormalities in systemic lupus erythematosus: correlations with neuropsychiatric impairment. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26:3634-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yi X, Wang X, Fu Y, Luo Y, Wang J, Han Z, Kuang Y, Chen X, Chen BT. Altered brain activity and cognitive impairment in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024;38:557-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sudheimer K, Keller J, Gomez R, Tennakoon L, Reiss A, Garrett A, Kenna H, O'Hara R, Schatzberg AF. Decreased hypothalamic functional connectivity with subgenual cortex in psychotic major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40:849-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]