Correlation analysis of lumbar disc degeneration characteristics and bone mineral density in patients with osteoporosis based on the Roussouly classification

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by reduced bone mass and deteriorating bone microarchitecture, leading to diminished bone strength and an increased risk of fractures (1,2). This condition can cause pain and deformity, severely impacting the quality of life, especially in postmenopausal women (3). With an ageing population, OP and fracture risk continue to rise (4), attracting attention.

The intervertebral disc (IVD) is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that connects adjacent vertebral bodies and consists of a proteoglycan-rich nucleus pulposus and a collagen-rich annulus fibrosus enveloped by cartilage endplates. The IVD provides structural support and absorbs shocks within the spinal column (5). Lumbar disc degeneration (LDD) is a chronic multifactorial irreversible process involving reduced proteoglycans and water content in the nucleus pulposus, IVD height loss, and morphological alterations, such as nucleus pulposus herniations and annulus fibrosus tears (6). These changes disrupt load distribution in the spine, leading to biomechanical alterations (7). Numerous studies have analyzed the relationship between LDD and bone mineral density (BMD); however, the association remains controversial. Wáng proposed that senile OP is linked to IVD degeneration (8). Geng et al. used quantitative computed tomography (QCT) to measure vertebral segmental BMD at L2–4. They revealed a significant correlation between LDD severity and reduced volumetric BMD of the vertebral body, particularly in males (9). As the largest avascular tissue in the human body, the IVD relies primarily on the cartilaginous endplates for nutrition (10). The endplate-disc-endplate complex supports the lumbar spine, bears pressure, and cushions longitudinal stress (11). Despite its importance, the endplate’s role is often overlooked, and its relationship with BMD remains unclear. Zhang et al. (12) employed quantitative QCT and found a significant negative correlation between volumetric BMD and endplate damage. However, Li et al. (13) utilized dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and found that the occurrence of endplate damage was associated with greater lumbar areal BMD values in patients with LDD. This may be due to osteophytes, which can lead to an overestimation of BMD measurements obtained via DXA.

Most patients with OP exhibit sagittal spinal imbalance (14), closely associated with vertebral compression fractures (15,16). In 2005, Roussouly (17) categorized the spine into four types based on different sagittal plane morphologies, including lumbar lordosis, pelvic incidence, and the inflection point from lumbar lordosis to thoracic kyphosis. Zhao et al. (18) found that type I or II patients are at a higher risk for severe LDD, particularly among those with type II morphology. Conversely, high-grade degeneration of the facet joints is more likely to occur in type III and IV patients, especially those with type IV. Rafael et al. (19) found higher degeneration in the L4/5 IVD among type II patients than in type IV patients in asymptomatic young individuals. These studies focus on spinal-pelvic sagittal plane morphology in lumbar degenerative changes; however, limited research exists on its impact on BMD and the correlation between BMD and LDD characteristics within different Roussouly types.

This study aimed to analyze degenerative changes in the IVD and endplates among patients with OP and investigate their relationship with BMD. Additionally, the study compared differences in LDD characteristics and their relationship with BMD among different Roussouly types. These findings contribute to a better understanding of LDD characteristics in patients with OP and provide valuable insights for personalized clinical management. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1872/rc).

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China (No. 2024-K-167-01), and the requirement for individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived. The target population was patients with OP who sought medical attention at The Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University between February 2017 and March 2024. The chief complaint was considerable lower back or lumbosacral pain without impairment in activities of daily living. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) lumbar spine T-score ≤−2.5; (II) age between 50 and 75 years; (III) complete medical records; (IV) examinations including DXA, lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and full-length anteroposterior and lateral spinal radiographs. MRI scans were required to be complete and clear, covering the L1–L5 vertebral bodies. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) history of spinal surgery; (II) presence of spinal spondylolisthesis, congenital spinal deformities, degenerative scoliosis (Cobb angle >10°), vertebral height loss exceeding one-third, or lower limb deformities; (III) patients with high IVD nuclear signal intensity coexisting with disc space narrowing at the same level, as the Pfirrmann grading did not provide a solution for such cases (20); (IV) use of medications affecting bone metabolism; (V) vertebral fractures, tumors, spinal tuberculosis, or other infectious diseases; (VI) diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, leukemia, or other conditions affecting bone density. Additionally, patients seeking treatment for mild lower back pain during routine physical examinations or outpatient visits comprised the control group. The inclusion criteria for the control group were T-score >−2.5, age over 50 years, and undergoing the same examinations during the same period. The exclusion criteria were consistent with those of the OP group.

Imaging procedures

Standard full-length anteroposterior and lateral spinal radiographs were obtained using a Siemens digital radiography system (SIEMENS YSIO; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and Picture Archiving and Communication System v3.0 (INFINITT; Shanghai, China). The following parameters were used: a current of 500 mA, voltage ranging from 50 to 75 kV, and automatic exposure mode. Standard radiographs were obtained using a well-established protocol. For anteroposterior imaging, participants stood with their arms naturally hanging down, palms facing forward, and feet together. For lateral imaging, participants placed their hands on their clavicles while extending their buttocks and knee joints.

The patients were examined using a 3.0 Tesla MRI scanner (MR750; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Prior to the examination, metallic objects on the patients’ bodies were removed. Patients were scanned in a supine position. Both arms were positioned flat on the sides of the body, and the lower limbs were uncrossed. Participants were instructed to remain still and relaxed throughout the process. Scanning included the vertebral bodies, adjacent structures, and surrounding soft tissues using routine sequences: sagittal fast spin-echo T1-weighted imaging (FSE-T1WI), sagittal and transverse fast spin-echo T2-weighted imaging (FSE-T2WI). The parameters for the sagittal T1WI scan were repetition time (TR), 1,050 ms; echo time (TE), 7 ms; nine slices with a thickness of 4 mm and an interslice gap of 0.5 mm, matrix size of 320×224, field of view (FOV) of 32 cm × 32 cm, two number of excitations (NEX), and a scan time of 2 minutes and 40 seconds. For the sagittal T2WI scan, the parameters were TR of 2500 ms, TE of 120 ms, nine slices with a thickness of 4 mm and an interslice gap of 0.5 mm, matrix size of 320×192, FOV of 32 cm × 32 cm, one NEX, and a scan time of 47 seconds. For the transverse T2WI scan, the parameters were TR of 3,000 ms, TE of 120 ms, 15 slices with a thickness of 3.5 mm and an interslice gap of 0.5 mm, matrix size of 320×224, FOV of 20 × 20 cm, one NEX, and a scan time of 1 minute and 22 seconds.

BMD values for the lumbar spine (L1–L4) and femoral neck were measured using a DXA device (GE Lunar Prodigy, Mexico), reported in g/cm2. These measurements were compared to peak BMD data of young, healthy young individuals in China to derive T-scores, which were employed to assess the patients’ OP status. This database is a collaborative initiative established through multiple centers nationwide and represents the only reference database for normal values specific to the mainland Chinese population (21). All patients underwent three examinations within a month and did not receive any OP treatment during that time.

Imaging evaluation

DXA

According to the standards established by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1994, . OP is characterized as a BMD that falls below 2.5 standard deviations of the peak bone mass of young, healthy individuals of the same ethnic group. This threshold for the T-score was initially proposed specifically for postmenopausal Caucasian women (4). Recently, Wáng (22) proposed that the application of traditional WHO standards to older Chinese women populations results in an overestimation of OP prevalence. Therefore, additional adjustments to the T-score threshold for defining OP in elderly individuals in China are recommended. For spinal assessments, the critical values should be −3.7 for women and −3.2 for men (23).

MRI

Disc dehydration grade

The grading system by Pfirrmann et al. (24) was employed to evaluate IVD degeneration at the L1/2–L5/S1 levels, utilizing T2-weighted sagittal images. This system assesses the signal intensity of the nucleus pulposus, the demarcation between the nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus, and the IVD height. It classifies LDD into grades I–V, each corresponding to a score ranging from one to five. Kwok et al.’s study (25) has shown that patients with OP have a decrease in vertebral body height but an increase in the middle height of IVD, suggesting that osteoporotic spines may be classified as having mild IVD degeneration. Therefore, in our study, the Pfirrmann score for IVD is solely indicative of the degree of dehydration of the disc nucleus. The average Pfirrmann L1/2–L5/S1 IVD scores were used to represent disc dehydration severity.

Grading of endplate damage

The method by Rajasekaran et al. (26) was employed to assess endplate damage. On T1-weighted sagittal images, the endplates were categorized into six grades, with higher scores indicating severe endplate damage. The total endplate damage score (TEPS) was calculated by adding the scores assigned to the upper and lower endplates of the L1/2–L5/S1 IVDs, with the average representing endplate damage severity (Figure 1).

Spine X-ray

Roussouly classification

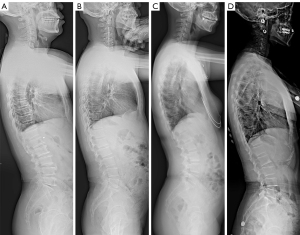

Using the Roussouly classification system (17), patients were stratified into four types. Type I: sacral slope (SS) <35° (shorter lumbar lordotic segment with a lower apex located near the L5 vertebral body and extended thoracic kyphosis spanning the entire thoracolumbar region). Type II: SS <35° (longer lumbar lordotic segment, minimal lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis, resulting in a nearly straight alignment). Type III: 35°< SS <45° (longer lumbar lordotic segment and apex positioned near the L4 vertebral body, displaying a noticeable lumbar lordotic curvature). Type IV: SS >45° (elongated lumbar lordotic segment extending into the thoracic region, apex located above the L3 vertebral body). In this type, the lumbar lordotic curvature is markedly pronounced, indicating evident hyperextension (Figure 2).

Osteophyte score

Studies have established that (27,28) osteophytes can influence BMD measurements using DXA, leading to potentially inflated results and false negative outcomes. Therefore, to assess the correlation between BMD and LDD characteristics, we controlled for osteophytes as a covariate. Following the X-ray osteophyte scoring criteria by Nathan (29) (Figure 3), we used full-length spinal X-ray images in the anteroposterior projection to evaluate the severity of osteophyte formation based on the most affected segment among the L1–5 vertebrae.

All scoring and spinal classifications were independently assessed by two radiologists, and a reassessment was conducted after 1 week. In case of disagreement, an experienced senior doctor made the final decision.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed using the statistical software SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R Studio (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The Shapiro-Wilk test assessed the normality of continuous variables. Regarding the inter-observer agreement of the IVD parameters, the Roussouly classification and osteophyte score (OSTS) were assessed using the Kappa test. Normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and BMD were compared between the two groups using an independent samples t-test, whereas sex was compared using the chi-square test. Differences in lumbar IVD parameters and OSTS were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The Kruskal-Wallis H test compared the differences in lumbar IVD parameters and OSTS among the four OP subgroups, followed by multiple comparisons within the subgroups. Analysis of variance was used for BMD comparison, and a post hoc analysis using the least significant difference test examined the differences among the subgroups. Spearman’s correlation was used to analyze the relationship between BMD and lumbar IVD parameters, with OSTS as a covariate. Significance was set at α=0.05 and P<0.05.

Results

A total of 300 patients, with a mean age of 62.05±7.02 years, were enrolled and stratified into OP and control groups based on lumbar spine T-score (≤−2.5). The OP group (n=150, 52 males, 98 females, mean age of 61.33±7.18 years) and control group (n=150, 60 males, 90 females, mean age 62.76±6.80 years) showed no significant differences in age, height, weight, BMI, or sex (P>0.05) (Table 1). Based on the classification criteria proposed by Wáng et al. (23), we further divided the OP group into two subgroups according to T-scores (women ≤−3.7, men ≤−3.2), designated as the OPA group and the OPB group (Table 2). The Kappa coefficients for the Pfirrmann grade, endplate damage grade, osteophyte score, and Roussouly classification of the OP group were 0.88 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.86–0.91], 0.88 (95% CI: 0.86–0.90), 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82–0.93), and 0.86 (95% CI: 0.80–0.93), respectively.

Table 1

| Demographics | OP group | Control group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.33±7.18 | 62.76±6.80 | 0.078 |

| Height (cm) | 160.58±8.62 | 157.41±6.68 | 0.099 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.46±12.42 | 57.54±9.13 | 0.350 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.74±3.31 | 23.23±3.43 | 0.965 |

| Sex | 0.34 | ||

| Male | 52 | 60 | |

| Female | 98 | 90 | |

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.759±0.101 | 1.086±0.156 | <0.001*** |

| OSTS | <0.001*** | ||

| 1 | 14 | 26 | |

| 2 | 102 | 98 | |

| 3 | 25 | 21 | |

| 4 | 9 | 5 |

Values are given as mean ± SD. ***, P≤0.001. OP, osteoporosis; BMI, body mass index; BMD, bone mineral density; OSTS, osteophyte score; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2

| Demographics | OPA group (n=39) | OPB group (n=111) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.46±6.47 | 62.51±6.91 | 0.456 |

| Height (cm) | 156.17±7.90 | 157.86±6.17 | 0.176 |

| Weight (kg) | 53.54±8.13 | 58.95±9.07 | 0.008** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.98±3.11 | 23.67±3.45 | 0.009** |

| Sex | 0.021* | ||

| Male | 20 | 32 | |

| Female | 19 | 79 | |

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.678±0.107 | 0.787±0.082 | <0.001*** |

| OSTS | 0.327 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 13 | |

| 2 | 29 | 73 | |

| 3 | 6 | 19 | |

| 4 | 3 | 6 |

OPA group: male T ≤−3.2, female T ≤−3.7; OPB group: female −2.5≤ T <−3.2, female -2.5≤ T <−3.7. Values are given as mean ± SD. *, P≤0.05; **, P≤0.01; ***, P≤0.001. OP, osteoporosis; BMI, body mass index; BMD, bone mineral density; OSTS, osteophyte score; SD, standard deviation.

The OP group (0.759±0.101 g/cm2) exhibited significantly lower BMD than the control group (1.086±0.156 g/cm2) (P<0.001). Also, the OP group showed higher segmental and average Pfirrmann scores, average TEPS, and OSTS than the control group (P<0.001) (Table 1, Figure 4). A total of 1,500 IVDs were included in this study.

In the control group, 46, 41, 42, and 21 patients were classified as types I–IV, according to the Roussouly classification, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed among the subgroups in terms of age, height, weight, BMI, or sex (P>0.05) (Table 3). Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were found in the average Pfirrmann scores and average TEPS at the L1/2–L5/S1 levels, as well as in BMD and OSTS among the four subtypes of patients (Table 3, Figure 5).

Table 3

| Demographics | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (n=46) | Type II (n=41) | Type III (n=42) | Type IV (n=21) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 60.52±7.05 | 63.68±7.08 | 59.93±7.17 | 61.33±7.04 | 0.085 |

| Height (cm) | 160.37±7.61 | 161.33±7.71 | 161.90±6.25 | 159.10±8.28 | 0.494 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.44±9.78 | 64.05±9.02 | 63.33±9.12 | 62.36±6.17 | 0.822 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.04±3.38 | 24.60±2.93 | 24.15±3.10 | 25.10±3.37 | 0.544 |

| Sex | 0.651 | ||||

| Male | 15 | 17 | 19 | 9 | |

| Female | 31 | 24 | 23 | 12 | |

| BMD (g/cm2) | 1.070±0.145 | 1.101±0.160 | 1.112±0.167 | 1.037±0.138 | 0.245 |

| OSTS | 0.217 | ||||

| 1 | 11 | 5 | 10 | 0 | |

| 2 | 29 | 29 | 23 | 17 | |

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 3 | |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

Values are given as mean ± SD. BMI, body mass index; BMD, bone mineral density; OSTS, osteophyte score; SD, standard deviation.

According to the Roussouly classification, patients in the OP group were categorized into four subgroups: type I (n=44), type II (n=46), type III (n=36), and type IV (n=24). Within each subgroup, no statistically significant differences were observed in age, height, weight, BMI, or sex (P>0.05). Type II (0.720±0.093 g/cm2) demonstrated significantly lower BMD than type I (0.768±0.122 g/cm2), type III (0.763±0.078 g/cm2), and type IV (0.809±0.078 g/cm2). In the L1/2–L5/S1 segments, type II exhibited significantly higher average Pfirrmann scores and average TEPS than types I, III, and IV. Type I also displayed significantly higher average Pfirrmann scores and average TEPS than type IV (P<0.05). In the L4/5 and L5/S1 segments, type II patients exhibited significantly higher Pfirrmann and endplate damage scores than type III and IV patients. Type I displayed significantly higher Pfirrmann and endplate damage scores than type IV. However, no significant differences were seen in Pfirrmann scores or endplate scores among the types in the L1/2, L2/3, and L3/4 segments (P>0.05). OSTS differed significantly among the different types, with type II patients exhibiting the highest (P<0.05) (Table 4, Figure 6).

Table 4

| Demographics | OP group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (n=44) | Type II (n=46) | Type III (n=36) | Type IV (n=24) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 62.86±6.80 | 62.00±6.80 | 63.58±7.21 | 62.79±6.56 | 0.777 |

| Height (cm) | 158.75±5.62 | 157.88±6.88 | 155.96±7.84 | 156.25±5.94 | 0.219 |

| Weight (kg) | 58.57±8.20 | 55.87±9.07 | 57.01±8.97 | 57.71±8.74 | 0.529 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.15±2.65 | 22.37±2.98 | 23.63±3.36 | 23.68±3.64 | 0.223 |

| Sex | 0.822 | ||||

| Male | 14 | 18 | 11 | 9 | |

| Female | 30 | 28 | 25 | 15 | |

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.768±0.122 | 0.720±0.093 | 0.763±0.078 | 0.809±0.078 | 0.003** |

| OSTS | 0.037* | ||||

| 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| 2 | 30 | 27 | 30 | 15 | |

| 3 | 7 | 12 | 1 | 5 | |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

Values are given as mean ± SD. *, P≤0.05; **, P≤0.01. OP, osteoporosis; BMI, body mass index; BMD, bone mineral density; OSTS, osteophyte score; SD, standard deviation.

Correlation analysis revealed a significant negative association between BMD and lumbar IVD parameters in the OP group (r=−0.424, −0.381; P<0.001) (Figure 7). After adjusting for gender and vertebral osteophytes as covariates, we found that the correlation coefficients between BMD and IVD parameters in the OPA group were significantly higher than those in the OPB group (r=−0.617, −0.403, −0.698, −0.198; P<0.05) (Figure 8). Additionally, types I, II, and III in the OP group demonstrated a negative correlation between BMD and average Pfirrmann scores as well as average TEPS (r=−0.310, −0.448, −0.382, −0.346, −0.396, −0.300; P<0.05) (Figures 9,10), with type II exhibiting a stronger correlation coefficient than types I and III. No significant correlation was observed between BMD and average Pfirrmann scores or average TEPS in type IV (P>0.05).

In the OP group, we observed that female patients had significantly lower BMD, along with higher average Pfirrmann scores and average TEPS compared to male patients (P<0.05), whereas no significant difference was found in the OSTS (P>0.05). Conversely, in the control group, no significant differences were found in IVD parameters, BMD, or OSTS between male and female patients (Figures S1,S2, Tables S1,S2). Our analysis revealed that the correlation between BMD density and IVD parameters in female patients of the OP group was significantly stronger than that observed in male patients (r=−0.416, −0.453, −0.389, −0.383, P<0.01) (Figure S3). We conducted a further analysis of the relationship between lumbar spine T-scores and femoral neck T-scores in the OP group, revealing a moderate positive correlation (r=0.641, P<0.001) (Figure S4).

Discussion

OP is a primary risk factor for fractures (30). Menopause induces endplate degeneration, which reduces the diffusion of nutrients to the IVD, ultimately leading to further LDD (31). However, the role of endplates is frequently overlooked, and limited attention has been given to the impact of spinal sagittal alignment on BMD and the correlation between BMD and LDD characteristics. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective analysis to assess LDD and endplate damage in patients with OP and investigate their relationship with BMD. Additionally, based on the Roussouly classification, we delved into the variations in LDD among patients with OP and different spinal types. These findings provide valuable insights for treating OP and LDD, offering potential guidance for individualized treatment and rehabilitation strategies to improve disease management and quality of life for patients.

In this study, patients with OP exhibited higher levels of disc nucleus dehydration and endplate damage compared to the control group. Several animal experiments have explored the relationship between BMD, LDD, and endplate damage. Xiao et al. (32) divided mice into experimental (OP-induced) and control (sham) groups. The experimental group showed more severe pathological features associated with LDD and endplate damage, including nucleus pulposus degeneration, endplate sclerosis, and annular tears, than the control group. Zhong et al. (33) used micro-computed tomography technology on rhesus monkeys, revealing that the group subjected to ovariectomy and streptomycin injection had increased endplate calcification areas and decreased vascularity compared with the other subgroups. Similar conclusions have been reached in human clinical studies, with patients with lower bone density showing more significant IVD degeneration and endplate damage (9,34). These findings are consistent with our results.

The IVD relies on diffusion from vascular buds in the cartilaginous endplate-disc junction for nutrition, which includes arteries, veins, capillaries, fibroblast-like cells, and macrophages (35). Blockage of these channels can disrupt nutrient supply, contributing to disc degeneration. Ou-Yang et al.’s study (36) on dynamic computed tomography perfusion revealed reduced microcirculatory perfusion, metabolic slowdown, and bone density in the lumbar vertebral bone marrow with age. OP increases the risk of microfractures and deformation in the trabeculae and endplates, leading to microvascular damage. Compression and distortion of the veins within the vertebral body increase pressure and impair blood circulation, causing issues in the blood supply to the cartilaginous endplates. This dramatically compromises the nutritional supply to IVD cells, contributing to disc degeneration (37).

The IVD is a crucial mechanical transmission structure for spinal movement and load-bearing, providing cushioning. The cartilaginous endplate primarily comprises type II collagen fibers and proteoglycans, rendering it excellent elasticity and compressive strength (38) and a vital source of nutrition for the IVD. Degenerative changes in the endplate are important pathological and physiological characteristics of LDD (39). In this study, a negative correlation was observed between BMD in patients with OP and the degree of disc nucleus dehydration and endplate damage. We hypothesized that in the presence of OP, increased spinal stress might hinder nutrient supply, impede waste clearance, and accelerate LDD. Kang et al. (40) employed finite element modelling to compare the physiological load differences between osteoporotic and normal spines under various motion scenarios. The findings indicated higher von Mises stress in the vertebral body, nucleus pulposus, and annulus fibrosus of the OP group, with pressure distribution maps revealing localized stress augmentation. Harada et al. (41) reported a negative correlation between lumbar BMD and the IVD area, as well as a positive correlation between BMD and the IVD protrusion rate. Consistent with their findings, our study revealed a negative correlation between BMD and the severity of disc nucleus dehydration and endplate damage. Previous studies have demonstrated that medications such as alendronate, risedronate, zoledronate, and denosumab can increase BMD in the spine or hip joints, thereby reducing the risk of fractures (42,43). Most research on these medications has predominantly focused on postmenopausal women with OP. In our study, we found that women are more prone to disc degeneration compared to men, a conclusion that is consistent with findings from previous studies (44,45). Furthermore, certain drugs have also shown the potential to increase IVD height and decrease endplate calcification (46). Therefore, when formulating treatment plans, clinicians should consider the combined impact of these medications on BMD and IVD characteristics. This provides a therapeutic strategy where anti-osteoporotic treatment in patients with OP can alleviate IVD degeneration, mitigate endplate damage, and improve spinal health, thus achieving a more comprehensive outcome.

Moreover, in this study, the correlation coefficients for the groups with adjusted T-score cutpoints were significantly higher than those for the groups prior to adjustment. Walker et al. (47) highlighted that postmenopausal Chinese women exhibit a higher trabecular plate-to-rod ratio, greater overall bone stiffness, and enhanced trabecular mechanical competence, whereas the risk of fragility fractures in this population is notably lower. Additionally, compared to older Caucasians, older Chinese men and women demonstrate milder degenerative changes in both bone and joints. Continuing to use the traditional T-score cutpoint of ≤−2.5 established for Caucasians may lead to a significant overestimation of OP prevalence in the Chinese population (23). Consequently, we further stratified the OP group into two subgroups based on T-score cutpoints of −3.2 for men and −3.7 for women. The results demonstrated that, following the adjustment of T-score cutpoints, the correlation coefficients between BMD and the degrees of disc dehydration and endplate damage were significantly higher, which supported the standards proposed by Wáng et al. (22,23). Adjusting the T-score cutpoints is essential for accurately assessing OP risk and prevalence in the Chinese population. These findings provide critical evidence for the development of more precise screening guidelines and personalized treatment strategies.

We utilized the Roussouly classification to categorize patients into four subgroups. Our findings revealed that in the OP group, type I and II patients exhibited a higher degree of disc nucleus dehydration and endplate damage at L1/2–L5/S1 than type III and IV patients. Type II patients exhibited more severe degeneration than type I patients and had lower BMD and higher OSTS than types I, III, and IV patients. Roussouly et al. (48) proposed that spinal forces result from gravitational forces and posterior spinal muscle strength categorized into two directions within each functional spinal unit: parallel and perpendicular to the endplate, influenced by endplate inclination. Type I and II patients have smaller lumbar curvatures, flatter backs, and a lower lumbar lordosis apex, with SS angles less than 35°, resulting in a concentration of forces on the anterior structures, specifically the vertebral bodies and IVDs (49,50). This distribution leads to higher perpendicular forces on the endplate and increased transmission of longitudinal loads through the lumbar IVDs than in type III and IV patients. Type II, known as ‘flat back’, is characterized by a more linear spinal alignment, reduced far-end curvature of the lumbar lordosis apex, and a more horizontally-oriented endplate inclination. Consequently, stress exerted perpendicular to the endplate was greater in type II than in type I, increasing the risk of OP, LDD, and endplate damage (48). Vertebral osteophytes are a characteristic feature of LDD (51). We postulate that type II patients may exhibit a higher severity of osteophytes, which can be correlated with the biomechanical loading conditions on their spinal column. Chen et al. (52) investigated the relationship between vertebral body marrow fat content and spinal sagittal alignment. Their findings revealed that types I and II exhibited higher bone marrow fat content levels in the L4 and L5 vertebral bodies than types III and IV. Another study of 243 patients with LDD showed that types I and II, particularly type II, were more likely to have advanced disc degeneration (18). These findings are consistent with our study results in the OP group. However, no significant differences were observed in the extent of disc nucleus dehydration, endplate damage, BMD, and OSTS among the four subgroups in the control group. We speculate that this may be attributed to the composition of the control group, which consisted of middle-aged patients and those aged over 50 years. These individuals inherently exhibit a certain degree of degeneration, and the influence of the Roussouly classification may be less pronounced compared with asymptomatic young and middle-aged individuals.

When comparing spinal segments, we only observed a similar degeneration pattern in the L4/5 and L5/S1 IVDs, consistent with the segment spanning from L1/2 to L5/S1. We speculate that this may be attributable to stress concentration in the lower lumbar region (53). Increased mechanical stress in this region can accelerate degeneration. Additionally, our study found that type II patients showed higher correlation coefficients between BMD and IVD parameters than type I and III patients. This confirms the relationship between OP, disc nucleus dehydration, and endplate damage, highlighting the importance of considering local degenerative damage within overall spinal morphology. Personalized preventive treatment measures can be implemented for type I and II patients. These may include adjusting body positioning to reduce spinal load and stress, as well as engaging in targeted exercises to strengthen the core muscles. Such measures are beneficial for maintaining spinal stability and can help prevent the occurrence and progression of OP, LDD, and osteophyte formation.

This study had some limitations. Indicators other than BMD were evaluated subjectively by two radiologists. Despite comprehensive training, some degree of subjectivity was inevitable, possibly influencing the findings. Although this study offered a relatively accurate assessment of nucleus pulposus dehydration, future research could benefit from incorporating quantitative evaluations of disc degeneration using techniques such as T2 mapping and T1rho to assess the biochemical composition of IVD. With its cross-sectional design, this retrospective study was conducted over an extended period and was prone to potential biases introduced by machine factors. Additionally, although this study considered the impact of osteophytes on BMD measurements, other factors, such as facet joint osteoarthritis or abdominal aortic calcification, which can affect BMD measurements, were not specifically excluded. Therefore, these factors might have influenced the accuracy of the results. Furthermore, this study utilized a cutpoint of T≤−2.5 for analysis. Although T-scores were adjusted for subgroup analysis, future research should adopt T-score cutpoints more suitable for the Chinese population: T≤−3.2 for male and T≤−3.7 for female. Alternatively, the use of QCT may provide a more accurate assessment of BMD. Moreover, this study excluded patients with fractures, whereas patients with OP are prone to develop vertebral fragility fractures. This leads to bias in the patient selection of our study. Future research should include patients with vertebral fractures to obtain more accurate results. Finally, this study represents a cross-sectional retrospective investigation, which currently precludes the establishment of causal relationships. Future longitudinal observational studies, integrating macroscopic and microscopic perspectives, are warranted to delve deeper into the intrinsic associations between the dynamic changes of OP and IVD degenerative alterations, as well as endplate damage.

Conclusions

Patients with OP exhibited higher degrees of LDD and endplate damage than the controls. A negative correlation was observed between BMD and the extent of LDD and endplate damage. Type II patients had the lowest BMD. Types I and II displayed significantly greater LDD and endplate damage than types III and IV, with type II patients experiencing more severe degeneration than type I. These findings enhance our understanding of LDD characteristics in patients with OP and offer novel insights for personalized clinical management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study and the staff from The Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1872/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1872/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China (No. 2024-K-167-01), and the requirement for individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rachner TD, Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis: now and the future. Lancet 2011;377:1276-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliorini F, Giorgino R, Hildebrand F, Spiezia F, Peretti GM, Alessandri-Bonetti M, Eschweiler J, Maffulli N. Fragility Fractures: Risk Factors and Management in the Elderly. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57:1119. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peterson JA. Osteoporosis overview. Geriatr Nurs 2001;22:17-21; quiz 22-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lane NE. Epidemiology, etiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:S3-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohd Isa IL, Teoh SL, Mohd Nor NH, Mokhtar SA. Discogenic Low Back Pain: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatments of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2022;24:208. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Modic MT, Ross JS. Lumbar degenerative disk disease. Radiology 2007;245:43-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vergroesen PP, Kingma I, Emanuel KS, Hoogendoorn RJ, Welting TJ, van Royen BJ, van Dieën JH, Smit TH. Mechanics and biology in intervertebral disc degeneration: a vicious circle. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:1057-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wáng YXJ. Senile osteoporosis is associated with disc degeneration. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2018;8:551-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geng J, Huang P, Wang L, Li Q, Liu Y, Yu A, Blake GM, Pei J, Cheng X. The association of lumbar disc degeneration with lumbar vertebral trabecular volumetric bone mineral density in an urban population of young and middle-aged community-dwelling Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study. J Bone Miner Metab 2023;41:522-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fields AJ, Ballatori A, Liebenberg EC, Lotz JC. Contribution of the endplates to disc degeneration. Curr Mol Biol Rep 2018;4:151-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Louie PK, Espinoza Orías AA, Fogg LF, LaBelle M, An HS, Andersson GBJ. Nozomu Inoue. Changes in Lumbar Endplate Area and Concavity Associated With Disc Degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:E1127-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Dou Y, Weng Y, Chen C, Zhao Q, Wan W, Bian H, Tian Y, Liu Y, Zhu S, Wang Z, Ma X, Liu X, Lu WW, Yang Q. Correlation Between Osteoporosis and Endplate Damage in Degenerative Disc Disease Patients: A Study Based on Phantom-Less Quantitative Computed Tomography and Total Endplate Scores. World Neurosurg 2024;192:e347-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li R, Zhang W, Xu Y, Ma L, Li Z, Yang D, Ding W. Vertebral endplate defects are associated with bone mineral density in lumbar degenerative disc disease. Eur Spine J 2022;31:2935-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga T, Miyagi M, Nakazawa T, Murata K, Kawakubo A, Fujimaki H, Koyama T, Kuroda A, Yokozeki Y, Mimura Y, Shirasawa E, Saito W, Imura T, Uchida K, Nanri Y, Inage K, Akazawa T, Ohtori S, Takaso M, Inoue G. Prevalence and Characteristics of Spinal Sagittal Malalignment in Patients with Osteoporosis. J Clin Med 2021;10:2827. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dai J, Yu X, Huang S, Fan L, Zhu G, Sun H, Tang X. Relationship between sagittal spinal alignment and the incidence of vertebral fracture in menopausal women with osteoporosis: a multicenter longitudinal follow-up study. Eur Spine J 2015;24:737-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi T, Iwata A, Kanayama M, Oha F, Hashimoto T, Iwasaki N. Impact of spino-pelvic and global spinal alignment on the risk of osteoporotic vertebral collapse. Spine Surg Relat Res 2018;2:72-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roussouly P, Gollogly S, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:346-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao B, Huang W, Lu X, Ma X, Wang H, Lu F, Xia X, Zou F, Jiang J. Association Between Roussouly Classification and Characteristics of Lumbar Degeneration. World Neurosurg 2022;163:e565-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menezes-Reis R, Bonugli GP, Dalto VF, da Silva Herrero CFP, Defino HLA, Nogueira-Barbosa MH. Association Between Lumbar Spine Sagittal Alignment and L4-L5 Disc Degeneration Among Asymptomatic Young Adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:E1081-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang YXJ. Several concerns on grading lumbar disc degeneration on MR image with Pfirrmann criteria. J Orthop Translat 2022;32:101-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng X, Dong S, Wang L, Feng J, Sun D, Zhang Q, Sun J, Wen Q, Hu R, Li N, Wang Q, Ma Y, Fu X, Zeng Q. Prevalence of osteoporosis in China: a multicenter, large-scale survey of a health checkup population. Chinese Journal of Health Management 2019;13:51-8.

- Wáng YXJ. The definition of spine bone mineral density (BMD)-classified osteoporosis and the much inflated prevalence of spine osteoporosis in older Chinese women when using the conventional cutpoint T-score of -2.5. Ann Transl Med 2022;10:1421. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wáng YXJ, Griffith JF, Blake GM, Diacinti D, Xiao BH, Yu W, Su Y, Jiang Y, Guglielmi G, Guermazi A, Kwok TCY. Revision of the 1994 World Health Organization T-score definition of osteoporosis for use in older East Asian women and men to reconcile it with their lifetime risk of fragility fracture. Skeletal Radiol 2024;53:609-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1873-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwok AW, Wang YX, Griffith JF, Deng M, Leung JC, Ahuja AT, Leung PC. Morphological changes of lumbar vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs associated with decrease in bone mineral density of the spine: a cross-sectional study in elderly subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:E1415-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajasekaran S, Venkatadass K, Naresh Babu J, Ganesh K, Shetty AP. Pharmacological enhancement of disc diffusion and differentiation of healthy, ageing and degenerated discs : Results from in-vivo serial post-contrast MRI studies in 365 human lumbar discs. Eur Spine J 2008;17:626-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, Harrington JT, McKinney RE Jr, McLellan A, Mitchell PJ, Silverman S, Singleton R, Siris E. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:2039-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tenne M, McGuigan F, Besjakov J, Gerdhem P, Åkesson K. Degenerative changes at the lumbar spine--implications for bone mineral density measurement in elderly women. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:1419-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nathan H. Compression of the sympathetic trunk by osteophytes of the vertebral column in the abdomen: an anatomical study with pathological and clinical considerations. Surgery 1968;63:609-25. [PubMed]

- Yong EL, Logan S. Menopausal osteoporosis: screening, prevention and treatment. Singapore Med J 2021;62:159-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang YX, Griffith JF. Menopause causes vertebral endplate degeneration and decrease in nutrient diffusion to the intervertebral discs. Med Hypotheses 2011;77:18-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiao ZF, Su GY, Hou Y, Chen SD, Zhao BD, He JB, Zhang JH, Chen YJ, Lin DK. Mechanics and Biology Interact in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: A Novel Composite Mouse Model. Calcif Tissue Int 2020;106:401-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhong R, Wei F, Wang L, Cui S, Chen N, Liu S, Zou X. The effects of intervertebral disc degeneration combined with osteoporosis on vascularization and microarchitecture of the endplate in rhesus monkeys. Eur Spine J 2016;25:2705-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang S, Lu K, Shi HJ, Shi Q, Gong YQ, Wang JL, Li C. Association between lumbar endplate damage and bone mineral density in patients with degenerative disc disease. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:762. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laffosse JM, Accadbled F, Molinier F, Bonnevialle N, de Gauzy JS, Swider P. Correlations between effective permeability and marrow contact channels surface of vertebral endplates. J Orthop Res 2010;28:1229-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ou-Yang L, Lu GM. Dysfunctional microcirculation of the lumbar vertebral marrow prior to the bone loss and intervertebral discal degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:E593-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seki S, Tsumaki N, Motomura H, Nogami M, Kawaguchi Y, Hori T, Suzuki K, Yahara Y, Higashimoto M, Oya T, Ikegawa S, Kimura T. Cartilage intermediate layer protein promotes lumbar disc degeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;446:876-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horner HA, Urban JP. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Basic Science Studies: Effect of nutrient supply on the viability of cells from the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:2543-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen C, Poiraudeau S, Rannou F. From Modic 1 vertebral-endplate subchondral bone signal changes detected by MRI to the concept of 'active discopathy'. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1488-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang S, Park CH, Jung H, Lee S, Min YS, Kim CH, Cho M, Jung GH, Kim DH, Kim KT, Hwang JM. Analysis of the physiological load on lumbar vertebrae in patients with osteoporosis: a finite-element study. Sci Rep 2022;12:11001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harada A, Okuizumi H, Miyagi N, Genda E. Correlation between bone mineral density and intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:857-61; discussion 862. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Colarossi G, Eschweiler J, Tingart M, Betsch M. Effect of drugs on bone mineral density in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:533. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliorini F, Colarossi G, Baroncini A, Eschweiler J, Tingart M, Maffulli N. Pharmacological Management of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: a Level I Evidence Based - Expert Opinion. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2021;14:105-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang YX, Griffith JF, Ma HT, Kwok AW, Leung JC, Yeung DK, Ahuja AT, Leung PC. Relationship between gender, bone mineral density, and disc degeneration in the lumbar spine: a study in elderly subjects using an eight-level MRI-based disc degeneration grading system. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:91-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lou C, Chen H, Mei L, Yu W, Zhu K, Liu F, Chen Z, Xiang G, Chen M, Weng Q, He D. Association between menopause and lumbar disc degeneration: an MRI study of 1,566 women and 1,382 men. Menopause 2017;24:1136-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou Z, Tian FM, Wang P, Gou Y, Zhang H, Song HP, Wang WY, Zhang L. Alendronate Prevents Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Adjacent to a Lumbar Fusion in Ovariectomized Rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:E1073-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker MD, Liu XS, Zhou B, Agarwal S, Liu G, McMahon DJ, Bilezikian JP, Guo XE. Premenopausal and postmenopausal differences in bone microstructure and mechanical competence in Chinese-American and white women. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:1308-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roussouly P, Pinheiro-Franco JL. Biomechanical analysis of the spino-pelvic organization and adaptation in pathology. Eur Spine J 2011;20:609-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang X, Kong Q, Song Y, Liu L, Zeng J, Xing R. The characteristics of spinopelvic sagittal alignment in patients with lumbar disc degenerative diseases. Eur Spine J 2014;23:569-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ergün T, Lakadamyalı H, Sahin MS. The relation between sagittal morphology of the lumbosacral spine and the degree of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2010;44:293-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pye SR, Reid DM, Lunt M, Adams JE, Silman AJ, O'Neill TW. Lumbar disc degeneration: association between osteophytes, end-plate sclerosis and disc space narrowing. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:330-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen F, Huang Y, Guo A, Ye P, He J, Chen S. Associations between vertebral bone marrow fat and sagittal spine alignment as assessed by chemical shift-encoding-based water-fat MRI. J Orthop Surg Res 2023;18:460. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keller TS, Colloca CJ, Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ. Influence of spine morphology on intervertebral disc loads and stresses in asymptomatic adults: implications for the ideal spine. Spine J 2005;5:297-309. [Crossref] [PubMed]