Evaluating failed dacryocystorhinostomy using computed tomography dacryocystography: a preliminary analysis of bony ostium characteristics in an Asian population

Introduction

Dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) is the gold standard surgical intervention for nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO), a condition characterized by persistent epiphora and recurrent infections that significantly impacts patients’ quality of life (1,2). Despite high success rates of 80–95% for both external (EXT-DCR) and endoscopic (EN-DCR) approaches (1,3,4), a subset of patients requires revision surgery due to persistent symptoms (5).

The success of DCR largely depends on creating and maintaining a patent osteotomy between the lacrimal sac and nasal cavity. Inappropriate bony ostium characteristics have been identified as one of the primary causes of DCR failure, particularly in endoscopic approaches (6-8). However, current understanding of ostium-related failures is predominantly based on subjective observations during revision surgeries, with limited quantitative analysis of the original ostium’s size, position, and morphology (8-10).

Previous studies have focused on ostium size and position; the potential impact of irregular ostium shape on DCR outcomes has been largely overlooked. Computed tomography dacryocystography (CT-DCG) has emerged as a pivotal tool in the assessment of the lacrimal drainage system, offering high-resolution, 3-dimensional (3D) visualization of the bony ostium (11,12). This allows for accurate assessment of osteotomy characteristics and complements the limitations of nasal endoscopy in evaluating bony structures and deep soft tissue changes (13,14).

This study aimed to utilize CT-DCG for a comprehensive, quantitative analysis of bony ostium morphology, dimensions, and position in patients with failed DCR surgeries, comparing these characteristics with those of successful cases. By employing this advanced imaging technique, we sought to identify key factors contributing to DCR failure, provide a more nuanced understanding of the role of ostium characteristics in surgical outcomes, and assess the value of CT-DCG in developing effective strategies for revision DCR and potentially improving primary DCR techniques. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1979/rc).

Methods

Study design and patient selection

This retrospective cohort preliminary study was conducted at the Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital of Fudan University from January 2022 to June 2024 in an Asian population. We included two groups: Group 1 consisted of 34 patients seeking revision surgery for failed DCR, and Group 2 comprised 16 bilateral NLDO patients with successful DCR in 1 eye who were seeking contralateral primary surgery. The sample size was determined based on the available cases meeting the inclusion criteria during the study period. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) age ≥18 years; (II) history of previous DCR surgery; and (III) scheduled for revision DCR or contralateral primary DCR. The exclusion criteria included acute dacryocystitis, canalicular obstruction, active rhinitis, or secondary NLDO due to neoplasia, trauma, sarcoidosis, or granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital of Fudan University (No. 2023164). Given the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for individual informed consent was waived.

CT-DCG protocol

CT-DCG imaging was performed using a 128-slice dual-source high-resolution scanner (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens, Erlanglen, Germany). Scanning parameters included 0.75 mm contiguous axial sections aligned parallel to the infraorbitomeatal line, with a bone window algorithm (width: 4,000 HU; level: 700 HU), and patients scanned in a supine position. The scanning range extended from the superior orbital rim to the inferior margin of the maxillary sinus.

After acquiring a baseline non-contrast scan, ioversol (320 mg I/mL) was irrigated into each canaliculus. A post-contrast scan was performed after a 5-minute delay to assess contrast distribution within the lacrimal drainage system. Multiplanar reformatting (MPR) was used to generate axial, coronal, and sagittal reconstructions using Syngo.via software (Version VB20A, Siemens Healthineers).

CT-DCG image analysis

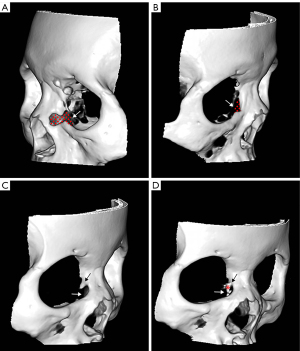

We generated 3D reconstructions from axial CT-DCG images and optimized them using Syngo.via software for enhanced osteotomy window visualization (Figure 1). Multiplanar reconstructed images were manipulated in 3D space to achieve optimal visualization planes for precise ostium measurements. The analysis protocol encompassed three primary parameters: ostium position, dimensions, and morphological characteristics.

Positional analysis evaluated four critical boundaries: (I) superior extent in relation to the common canaliculus and upper lacrimal sac; (II) inferior extent relative to the bony nasolacrimal canal opening; and (III) anterior and (IV)posterior margins in relation to the contrast-delineated lacrimal sac boundaries. An adequate osteotomy was defined by extension beyond these anatomical landmarks in all four directions.

Dimensional analysis comprised quantitative measurements of maximum anteroposterior diameter (height), maximum craniocaudal diameter (width), minimum diameter (shortest side), and total ostium area. The 3D orientation of each ostium was standardized through spatial rotation to ensure accurate dimensional measurements irrespective of the original surgical orientation. Morphological assessment utilized standardized criteria: regular ostia were defined as complete quadrilaterals with parallel sides of approximately equal length and standard angles, whereas irregular ostia were characterized by non-quadrilateral configurations, asymmetric sides (length ratio >2:1), or irregular contours (Figure 2). The presence of residual obstructing bone along the lacrimal drainage pathway was documented (Figure 2).

All measurements were independently performed by two observers blinded to clinical outcomes, and mean values from both observers were used for subsequent analysis.

Preoperative nasal endoscopy examination

Preoperative nasal endoscopy was performed using a 0° rigid endoscope (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany), and the findings were carefully evaluated by a single experienced otolaryngologist who was blinded to the CT-DCG results. The examination systematically assessed the following: (I) ostium visibility and patency; (II) presence and severity of adhesions in the middle meatal area; (III) mucosal inflammation, graded as mild, moderate, or severe; (IV) presence of nasal septal deviation; and (V) development of granulation tissue at the surgical site. All findings were documented using standardized protocols.

Intraoperative assessment

All failed DCR cases underwent endoscopic revision surgery, performed and evaluated by the same surgeon who conducted the original procedures. Intraoperative evaluation focused on three primary aspects: (I) bony ostium morphology, including size adequacy, position relative to the lacrimal sac, shape regularity, and presence of residual bone along the drainage pathway; (II) lacrimal sac characteristics, such as dimensions (documenting any size reduction) and wall integrity; and (III) nasal cavity features, particularly middle turbinate adhesions and significant anatomical variations. Surgical modifications were performed for cases with inadequate ostium findings, whereas alternative contributing factors were investigated when the ostium was deemed sufficient. All findings were documented using a standardized assessment protocol that captured both single and multiple contributing factors, with measurements and assessments recorded during endoscopic visualization.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between failed and successful DCR sides were performed using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. A two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the software SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient demographics

The preliminary study included 34 failed DCR cases and 16 successful DCR cases. In Group 1 (failed DCR), 12 patients (35.3%) had unilateral NLDO and 22 patients (64.7%) had bilateral NLDO. In Group 2 (successful DCR), all patients had bilateral NLDO with successful DCR in 1 eye. In the failed DCR group, the mean age was 54.76±9.53 years, with 31 (91.2%) females, and the mean time since previous surgery was 4.95±5.46 years. The successful DCR group had a mean age of 54.18±6.75 years, with 13 (81.3%) females, and a mean time since previous surgery of 5.50±8.21 years. Regarding surgical techniques, 18 (52.9%) failed cases underwent EN-DCR and 16 (47.1%) EXT-DCR, whereas in the successful group, 9 (56.3%) underwent EN-DCR and 7 (43.8%) EXT-DCR. There were no statistically significant differences in these demographic characteristics (all P>0.05, Table 1), suggesting that age, gender, time since previous surgery, and type of previous DCR were not determining factors in DCR success or failure.

Table 1

| Characteristic/finding | Failed DCR (n=34) | Successful DCR (n=16) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 54.76±9.53 | 54.18±6.75 | 0.82 |

| Female | 31 (91.2) | 13 (81.3) | 0.31 |

| Time since previous surgery (years) | 4.95±5.46 | 5.50±8.21 | 0.77 |

| Previous EN-DCR | 18 (52.9) | 9 (56.3) | 0.83 |

| CT-DCG findings | |||

| Position | |||

| Osteotomy not higher than half lacrimal sac | 14 (41.2) | 0 | <0.001* |

| Osteotomy not reaching common canaliculus | 23 (67.6) | 5 (31.3) | 0.017* |

| Lower osteotomy not low enough | 8 (23.5) | 0 | 0.038* |

| Osteotomy not covering anterior lacrimal sac | 13 (38.2) | 0 | 0.003* |

| Osteotomy not reaching posterior lacrimal sac | 10 (29.4) | 0 | 0.016* |

| Adequate osteotomy | 5 (14.7) | 16 (100.0) | <0.001* |

| Dimensions | |||

| Osteotomy width (mm) | 6.73±2.85 | 8.24±2.87 | 0.1 |

| Osteotomy height (mm) | 8.73±3.09 | 10.03±1.64 | 0.13 |

| The mean area of the bony ostium (mm2) | 38.25±25.21 | 75.12±31.15 | <0.001* |

| The shortest side of the osteotomy (mm) | 3.68±1.11 | 5.43±1.72 | <0.001* |

| Irregular osteotomy shape | 16 (47.1) | 2 (12.5) | 0.019* |

| Residual bone obstructing drainage | 24 (70.6) | 1 (6.3) | <0.001* |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). *, P<0.05. CT-DCG, computed tomography dacryocystography; DCR, dacryocystorhinostomy; EN-DCR, endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy; SD, standard deviation.

The position of osteotomy window

CT-DCG analysis revealed distinct patterns in osteotomy positioning between EXT-DCR and EN-DCR approaches, with outcomes detailed in Table 1. In EXT-DCR procedures, the osteotomy was characteristically anterior-focused with extensive maxillary bone removal, though often lacking adequate posterior extension (Figure 3A,3B). EN-DCR procedures, in contrast, tended to create more inferiorly positioned osteotomies, sometimes failing to achieve sufficient superior extension for optimal lacrimal sac exposure (Figure 3C,3D).

Analysis of success rates within each approach revealed specific patterns. For EXT-DCR, successful cases demonstrated osteotomies that: (I) surpassed the common canaliculus (68.7%); (II) extended higher than half of the lacrimal sac (100%); (III) reached below the bony nasolacrimal canal opening (100%); and (IV) adequately covered both anterior and posterior lacrimal sac margins. Failed EXT-DCR cases showed inadequate posterior extension and variable superior limits, with only 32.4% surpassing the common canaliculus and 58.8% reaching above half the lacrimal sac height.

In EN-DCR procedures, successful cases consistently achieved adequate inferior extension below the bony nasolacrimal canal opening. However, the key difference in failed cases was insufficient superior extension, with the osteotomy failing to surpass the common canaliculus in many instances. Failed EN-DCR cases also showed inadequate coverage of the anterior lacrimal sac margin in 38.2% of cases and insufficient posterior extension in 29.4% of cases (P=0.003 and P=0.016, respectively).

Shape and size of osteotomy window

The evaluation of osteotomy shape and size revealed significant differences between the failed and successful groups. Irregular osteotomy shape was more frequent in the failed group (47.1% vs. 12.5%, P=0.019). Although the mean osteotomy width (6.73±2.85 vs. 8.24±2.87 mm, P=0.1) and height (8.73±3.09 vs. 10.03±1.64 mm, P=0.13) were not significantly different between the failed and successful groups, other dimensions showed marked disparities. The shortest side of the osteotomy was significantly smaller in the failed group (3.68±1.11 vs. 5.43±1.72 mm, P<0.001). Moreover, the mean area of the bony ostium was substantially reduced in failed cases (38.25±25.21 vs. 75.12±31.15 mm2, P<0.001). These findings suggest that although overall width and height may not be decisive factors, the uniformity of the ostium shape and its total area are critical for successful outcomes. Notably, residual bone obstructing drainage was observed in 70.6% of failed cases compared to only 6.3% of successful cases (P<0.001), further highlighting the importance of complete osteotomy in DCR procedures.

Findings of nasal endoscopy examination

Nasal endoscopy demonstrated marked differences between the groups. Ostium visibility was significantly lower in the failed group (32.4% vs. 93.8%, P<0.001). The failed group showed higher rates of adhesions (41.2% vs. 6.3%, P=0.011) and moderate to severe inflammation (55.9% vs. 18.8%, P=0.013). Nasal septal deviation was more common in the failed group (32.4% vs. 12.5%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.127). Excessive granulation tissue was observed exclusively in the failed group (26.5% vs. 0%, P=0.022). These findings suggest that post-surgical nasal cavity changes, including adhesions, inflammation, and granulation tissue, play a crucial role in DCR outcomes. Detailed data for all parameters are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Finding | Failed DCR (n=34) | Successful DCR (n=16) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal endoscopy findings | |||

| Visible ostium | 11 (32.4) | 15 (93.8) | <0.001* |

| Adhesions | 14 (41.2) | 1 (6.3) | 0.011* |

| Moderate to severe inflammation | 19 (55.9) | 3 (18.8) | 0.013* |

| Nasal septal deviation | 11 (32.4) | 2 (12.5) | 0.127 |

| Excessive granulation tissue | 9 (26.5) | 0 | 0.022* |

| Intraoperative findings† | |||

| Inappropriate bony ostium characteristics | 28 (82.4) | – | – |

| Insufficient size | 6 (17.6) | – | – |

| Inappropriate positioning | 15 (44.1) | – | – |

| Irregular ostium shape | 7 (20.6) | – | – |

| Multiple contributing factors | 12 (35.3) | – | – |

| Lacrimal sac abnormalities | 5 (14.7) | – | – |

| Reduced sac size | 3 (8.8) | – | – |

| Significant wall thickening | 2 (5.9) | – | – |

| Middle turbinate adhesions | 4 (11.8) | – | – |

| Significant nasal cavity narrowing | 2 (5.9) | – | – |

*, P<0.05; †, intraoperative findings were only available for failed DCR cases undergoing revision surgery. DCR, dacryocystorhinostomy.

Intraoperative assessment findings

Endoscopic evaluation of the 34 failed DCR cases revealed significant anatomical and pathological variations. Inappropriate bony ostium characteristics were found in 28 cases (82.4%). Among these, 6 cases (17.6%) had insufficient size, 15 cases (44.1%) showed inappropriate positioning relative to the lacrimal sac, and 7 cases (20.6%) presented with irregular ostium shapes. Notably, all 24 cases with insufficient ostium characteristics exhibited residual bone obstructing the drainage pathway. In the remaining 6 cases (17.6%) where the ostium was deemed adequate in terms of size, position, and shape, other factors were identified as potential contributors to failure. These included middle turbinate adhesions in 4 cases (11.8%) and significant nasal cavity narrowing in 2 cases (5.9%).

Multiple factors were often present, with 12 cases (35.3%) showing a combination of issues contributing to DCR failure. Lacrimal sac abnormalities were observed in 5 cases (14.7%), including 3 cases (8.8%) with reduced sac size and 2 cases (5.9%) exhibiting significant wall thickening. The most common combination, noted in 7 cases (20.6%), involved inadequate ostium size alongside lacrimal sac abnormalities, emphasizing the complexity of revision surgeries in these patients.

Discussion

This study utilized a multi-modal approach combining CT-DCG, nasal endoscopy, and intraoperative observations to analyze failed and successful DCR cases. Our findings revealed significant differences in bony ostium characteristics and soft tissue factors between these groups, with only 14.7% of failed cases demonstrating adequate osteotomy compared to 100% in the successful group. This stark contrast aligns with recent studies emphasizing the importance of ostium size and position (11,15), whereas our quantitative analysis provided more precise data on these parameters.

Ethnic anatomical variations play a critical role in DCR outcomes, influencing both surgical technique and results. Asian populations, for example, typically exhibit thicker facial bones, narrower nasolacrimal duct lumens, and more constricted intranasal structures than other ethnic groups (13,16-18). These anatomical differences affect the surgical approach, particularly in achieving uniform ostium shapes and complete bone removal, both of which are crucial for successful DCR (19). Our analysis underscores the importance of these variations, suggesting that tailored surgical approaches may be necessary to optimize outcomes in Asian patients.

The position of the bony ostium emerged as a primary factor in DCR failure, with distinct patterns observed between EN-DCR and EXT-DCR approaches in Asian patients. EN-DCR failures often exhibited inferiorly positioned ostia, which may be attributed to the higher position of the lacrimal sac relative to the middle turbinate insertion in Asian populations (13,20). This anatomical variation can lead surgeons to create a lower ostium to align with the middle meatus, potentially resulting in inappropriate positioning. Conversely, EXT-DCR failures typically showed anteriorly displaced ostia with insufficient posterior coverage. This outcome likely stems from the thicker facial bones and narrower nasal circumstances characteristic of Asian patients (21). The denser bone structure may prompt surgeons to position the ostium more anteriorly to avoid complications, whereas the narrow nasal cavity limits access to the posterior lacrimal sac. These findings emphasize the need for tailored approaches that account for ethnic anatomical variations to improve DCR outcomes (22).

Our analysis revealed that although mean ostium dimensions did not differ significantly between failed and successful DCR groups (P>0.05), the uniformity of the ostium and the presence of residual bones emerged as critical factors. Failed DCR cases exhibited a significantly higher incidence of irregular ostium shapes compared to successful cases. These irregularities often manifested as asymmetrical margins, which may impede proper mucosal apposition and healing. Moreover, the presence of residual bone was observed more frequently in failed cases, obstructing the drainage pathway and promoting fibrosis or granulation tissue formation. These findings underscore the importance of achieving not only an adequately sized, but also a uniform and completely cleared, ostium during DCR procedures. Future surgical techniques should prioritize creating smooth, regular ostium shapes and ensuring thorough osteotomy to enhance outcomes.

Nasal endoscopy revealed the significant role of soft tissue factors in DCR outcomes. Failed cases showed higher rates of adhesions, scarring, and inflammation, emphasizing that DCR success depends on both bony ostium characteristics and the health of surrounding nasal mucosa. These observations are consistent with those of others (23), who reported on the impact of postoperative mucosal conditions on DCR outcomes. Our results further emphasize the importance of meticulous mucosal preservation and careful postoperative care to optimize surgical outcomes (24).

Intraoperative observations corroborated CT-DCG findings while revealing additional factors, particularly regarding lacrimal sac condition. Some failed cases exhibited smaller or thick-walled lacrimal sacs, a finding that has received limited attention in previous DCR outcome studies (8). Recent research has further emphasized the importance of these anatomical considerations, with studies demonstrating that wider osteotomies in retrograde DCR procedures significantly improve surgical outcomes (19). These collective findings suggest that future research and surgical planning should consider lacrimal sac parameters alongside ostium metrics, potentially leading to more personalized surgical approaches.

This preliminary study has several limitations. The sample size, especially in the successful DCR group, was small, limiting our ability to conduct more detailed subgroup analyses, such as examining technique-specific factors in EN-DCR and EXT-DCR. The CT-DCG imaging, despite providing high-resolution reconstructions, has limitations in visualizing thin lacrimal bones, which could affect the assessment of the posterior bony ostium. Furthermore, the retrospective design, single-institution setting, and lack of long-term follow-up data limit the generalizability of our findings. Some intraoperative findings relied on qualitative assessments, highlighting the need for more standardized measures in future studies.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1979/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1979/coif). Both authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital of Fudan University (No. 2023164). The requirement for individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Vinciguerra A, Nonis A, Giordano Resti A, Bussi M, Trimarchi M. Best treatments available for distal acquired lacrimal obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2020;45:545-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang D, Xiang N, Hu WK, Luo B, Xiao XT, Zhao Y, Li B, Liu R. Detection & analysis of inflammatory cytokines in tears of patients with lacrimal duct obstruction. Indian J Med Res 2021;154:888-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coumou AD, Genders SW, Smid TM, Saeed P. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: long-term experience and outcomes. Acta Ophthalmol 2017;95:74-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajabi MT, Shahraki K, Nozare A, Moravej Z, Tavakolizadeh S, Salim RE, Hosseinzadeh F, Mohammadi S, Farahi A, Shahraki K. External versus Endoscopic Dacryocystorhinostomy for Primary Acquired Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2022;29:1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin GC, Brook CD, Hatton MP, Metson R. Causes of dacryocystorhinostomy failure: External versus endoscopic approach. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2017;31:181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keren S, Abergel A, Manor A, Rosenblatt A, Koenigstein D, Leibovitch I, Ben Cnaan R. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: reasons for failure. Eye (Lond) 2020;34:948-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deosthale N, Garikapati P, Choudhary S, Khadakkar S, Deshpande A, Mangade S, Dhote K. Surgical Outcome of Endoscopic Dacryocystorhinostomy with and Without Prolene Stent in Chronic Dacryocystitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2023;75:3443-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Bouhmadi K, Loudghiri M, Oukessou Y, Rouadi S, Abada R, Roubal M, Mahtar M. Evaluation of the endoscopic revision of dacryocystorhinostomy failure cases: a cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2023;85:4218-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu B, Mao B, Tu Y, Wang M, Wu W. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with and without bicanalicular silicone tube in patients with a small lacrimal sac: a comparative study. Rhinology 2024;62:623-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nie S, Liu Y, Wang W, Guo L, Zhou M, Zhang Y, Li D, Chen Q, Huang D, Liang X, Chen R. Clinical utility of digital radiography dacryocystography for preoperative assessment in nasolacrimal duct obstruction prior to endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Heliyon 2024;10:e31981. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gökçek A, Argin MA, Altintas AK. Comparison of failed and successful dacryocystorhinostomy by using computed tomographic dacryocystography findings. Eur J Ophthalmol 2005;15:523-9. [Crossref]

- Liu Y, Jiang A, Nie S, Cao S, Wumaier A, Ding R, Kuerban M, Zhou R, Lin F, Yang H, Liang X, Huang D, Chen R. CT-Measured Angulation Between the Frontal Bone and Bony Nasolacrimal Duct: Variations in Obstructed and Healthy Lacrimal Ducts. Semin Ophthalmol 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woo KI, Maeng HS, Kim YD. Characteristics of intranasal structures for endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy in asians. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;152:491-498.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nomura K, Arakawa K, Sugawara M, Hidaka H, Suzuki J, Katori Y. Factors influencing endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy outcome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017;274:2773-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammoudi DS, Tucker NA. Factors associated with outcome of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;27:266-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fayet B, Racy E, Assouline M, Zerbib M. Surgical anatomy of the lacrimal fossa a prospective computed tomodensitometry scan analysis. Ophthalmology 2005;112:1119-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Wang P, Du L, Wang L. The Anatomy of the Frontal Process of the Maxilla in the Medial Wall of the Lacrimal Drainage System in East Asians. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2021;37:439-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soyka MB, Treumann T, Schlegel CT. The Agger Nasi cell and uncinate process, the keys to proper access to the nasolacrimal drainage system. Rhinology 2010;48:364-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alicandri-Ciufelli M, Lucidi D, Aggazzotti Cavazza E, Russo P, Del Giovane C, Marchioni D, Calvaruso F. Classical vs. Retrograde Endoscopic Dacryocystorhinostomy: Analyses and Comparison of the Results. J Clin Med 2024;13:3824. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Purevdorj B, Dugarsuren U, Tuvaan B, Jamiyanjav B. Anatomy of lacrimal sac fossa affecting success rate in endoscopic and external dacryocystorhinostomy surgery in Mongolians. Anat Cell Biol 2021;54:441-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang W, Gong L, Wang Y. Anatomic characteristics of primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction: a comparative computed tomography study. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2022;12:5068-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cui X, Wang Y. Assessing the relationship of agger nasi pneumatization to the lacrimal sac: a dynamic computed tomography-dacryocystography analysis. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2024;14:5642-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Konuk O, Kurtulmusoglu M, Knatova Z, Unal M. Unsuccessful lacrimal surgery: causative factors and results of surgical management in a tertiary referral center. Ophthalmologica 2010;224:361-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Codère F, Denton P, Corona J. Endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: a modified technique with preservation of the nasal and lacrimal mucosa. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;26:161-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]