Development and validation of a novel echocardiography-based nomogram for the streamlined classification of cardiac tumors in cancer patients

Introduction

Neoplasms of the heart are relatively infrequent compared to those of other organs (1-3), with incidence rates ranging from 0.0017% to 0.19%, as delineated by several autopsy series in non-selected cohorts (4,5). Previous studies have indicated that approximately 90% of primary cardiac tumors are benign. However, with the increasing prevalence of individuals living with cancer, evidence has emerged suggesting that approximately 14.2% of extracardiac malignancies eventually culminate in metastasis to cardiac tissue (5-7). This phenomenon complicates the differentiation between benign and malignant cardiac tumors, particularly in patients with extracardiac malignancies. More importantly, future therapeutic approaches, such as anticancer therapies or cardiac operations, which affect the prognosis stratification, quality, and span of life for these patients, could be directly determined (5,8).

Thus far, distinguishing metastatic malignancies from primary benign cardiac tumors remains a challenge (6,9). Most cardiac tumors are asymptomatic and lack specific serum biomarkers for identification (1). Although pathological biopsy is the diagnostic gold standard, it is often limited by the risks and difficulties of specimen acquisition (10). Several clinical red flags for malignancy, such as age, male sex, and dyspnea in New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes III and IV, have been previously proposed in the literature as key indicators of malignant cardiac tumors. These clinical features, in conjunction with imaging findings, can provide important clues for distinguishing between benign and malignant cardiac tumors (11,12). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) remains the first-line diagnostic tool due to its characteristic of being portable and economical (2). Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is the gold standard imaging modality for evaluating cardiac masses, providing superior tissue characterization and diagnostic accuracy. Studies by Shenoy et al. and Paolisso et al. have demonstrated nearly perfect diagnostic performance of CMR in identifying cardiac tumors (13,14). However, CMR is less commonly used due to its high costs and contraindications. In fact, echocardiography is reported to outperform CMR in detecting small and mobile tumors because of its higher spatial and temporal resolution (1). Other modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET), are useful for staging but are limited by risks such as radiation exposure and contrast-induced nephropathy.

Previous investigations have demonstrated a robust correlation between echocardiographic findings of cardiac masses and malignant pathologies within a cohort of histologically-confirmed cases (15). Attempts have been made to develop a scoring system from echocardiographic data to predict the likelihood of malignancy in cardiac tumors (16). However, the interpretation of ultrasonic findings inherently relies on the clinician’s expertise and is subject to variability. Although contrast-enhanced echocardiography offers enhanced diagnostic value for identifying malignancies (9), its application is limited by the associated high costs and time requirements, which pose challenges in the accurate diagnosis of cardiac tumors. Thus, the development of an advanced, streamlined diagnostic strategy to support and improve diagnostic accuracy is imperative.

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a significant analysis tool in noninvasive medical imaging, revealing that images harbor information extending beyond their visual content (17,18). In recent years, ML methods have been applied to ultrasound (US) imaging, providing insights into the relationship between radiomic features and malignant lesions (19-21). Among them, some researchers have developed a practical model integrating US-based radiomics and clinical indicators, demonstrating superior accuracy in distinguishing malignant from benign renal masses compared to primary physicians (22). Therefore, we hypothesized that ML analysis holds significant promise for obtaining valuable insights from echocardiograms, facilitating the classification of cardiac tumors in patients with known malignancies. Acknowledging the critical importance of baseline and gross echocardiographic characteristics, a combined nomogram model integrating some of these main findings with the ML framework was devised. The validity and performance of the model were subsequently evaluated and benchmarked against the diagnostic capabilities of both junior and senior physicians. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1096/rc).

Methods

Patient datasets

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital (No. TJ-IRB20210227) and the need to obtain written informed consent from all patients was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study. This study retrospectively and consecutively collected data from patients who were diagnosed with cardiac masses by echocardiography between April 2008 and June 2022 in Tongji Hospital. Figure 1 shows the complete workflow of this study. To ensure a focused analysis and feasibility of model development in a specific cancer patient cohort, the inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (I) a spectrum of specific extracardiac malignancies; (II) confirmed malignant or benign cardiac tumors, based on a combination of methodologies: (i) surgical/biopsy pathology evidence available; (ii) response to anticancer therapy, evaluated using baseline and follow-up imaging assessments, in accordance with Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 guidelines (23), a malignant nature was confirmed with complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) to chemotherapy; (iii) comprehensive multimodal imaging assessment for cases where surgical pathology was not feasible. Multimodal imaging techniques included contrast echocardiography, CMR/with gadolinium administration, CT/with iodine contrast administration, and PET combined with CT. CMR and PET/CT analysis and evaluation illustrations are supplied in supplement material (Appendix 1); and (III) at least one echocardiographic clip clearly depicting the cardiac tumors across 3–5 stable cardiac cycles available. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) unidentified extracardiac malignancies; (II) thrombi or multifocal lesions, which were defined as the presence of multiple tumors in various cardiac chambers; and (III) poor image quality that was unsuitable for radiomics analysis.

A computer-based randomization method was used to divide all enrolled echocardiographic clips of patients into training and test sets at a proper ratio. The training set was used for model development, whereas the test set was used for model validation.

Echocardiography acquisition

TTE was conducted in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography’s guidelines by experienced sonographers using US devices [Vivid series, GE Healthcare (Chicago, IL, USA) or EPIQ series, Philips Healthcare (Amsterdam, the Netherlands)] equipped with a 1.5–3.5-MHz probe. The frame rates varied between 30 and 60 fps. The procedure captured standard parasternal long- and short-axis views, three apical views (4-chamber, 2-chamber, and 3-chamber), and some nonstandard views with patients in the left lateral decubitus position. Digital loops for 3–5 consecutive heartbeats were stored in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format.

Radiomics signature development

Tumor segmentation

For each echocardiographic clip, two experienced sonographers (with 3 and 5 years of experience) who were blinded to the pathology precisely outlined the cardiac tumors at the clearest frame using ITK-SNAP software (version 3.8.0; http://www.itksnap.org/). In instances where multiple tumors existed within a cardiac chamber, we used the largest and clearest lesion as the target for delineating the region of interest (ROI). Manual adjustments were carried out by tracking the changes from frame to frame within the clips, ensuring that the tumor remained within the outlined contours at every image frame.

Feature extraction

Based on the original images and segmented ROIs, we utilized PyRadiomics (version 3.1.0; https://www.radiomics.io/pyradiomics.html) to extract radiomic features. [including 938 radiomics features with the mean and standard deviation (std)] (24). These features include grayscale statistic (GSS) features derived from the histogram of tumor voxel intensities, such as variance, skewness, and kurtosis; texture features from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), gray-level run-length matrix (GLRLM), gray-level size zone matrix (GLSZM), and neighborhood gray-tone difference matrix (NGTDM); and wavelet features encompassing a variety of statistical, shape-based, and textural analyses.

Furthermore, the optical flow algorithm within the OpenCV framework (version 4.6.0) was utilized to evaluate the kinematic attributes of the cardiac neoplasm. For each video segment, two principal parameters were quantified: the mean pixel velocity and the corresponding standard deviation across the tumor region. The mean pixel velocity is indicative of the overall velocity magnitude of the neoplasm, whereas the standard deviation provides a measure of the consistency of motion within the tumor mass.

Feature standardization and selection

Before performing feature selection, we applied Z score normalization to the radiomic features of both the training and validation sets. This was performed to address the influence of high-dimensional data on the study.

The process of feature selection, executed via the scikit-learn toolkit (version 1.2.1), encompassed a 2-fold approach: initially, the 100 most salient features were ascertained utilizing a mutual information criterion; subsequently, a more refined reduction was implemented through recursive feature elimination (RFE). This latter step incorporated strategies such as low-variance filtering, correlation-based feature selection, L1-norm regularization, and ensemble-based techniques to obtain the optimal feature subset.

Radiomics signature computation

Based on the selected features, we constructed a radiomic framework using ML algorithms such as random forest (RF), AdaBoost (AB), and decision tree (DT), coupled with 4-fold cross-validation. Radiomic signatures were developed based on this ML framework. Their discrimination performance was evaluated using model assessment indicators, such as sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Ultimately, a refined radiomic framework was determined based on the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). Subsequently, visualization of the importance of significant features and computation of the radiomic score (Rad-score) as a radiomic signature were carried out based on this optimal framework.

Non-experience-dependent indicator (NDI) collection

The NDIs, meticulously selected by three sonographers each with a decade of diagnostic expertise and blinded to pathology, were designed to ensure that evaluations and identifications remain accurate and consistent, even when conducted by novice physicians. These indicators encompass both clinical baselines, including sex and age, as well as five objective and gross echocardiographic manifestations indicative of cardiac tumors. The detailed echocardiographic indicators are as follows: (I) the anatomical localization of the cardiac neoplasm, either within the right heart circulatory system (comprising the vena cava, right atrium and ventricle, and pulmonary artery) or the left heart circulatory system (encompassing the left ventricle, left atrium, and aorta), within the myocardial tissue, or the pericardial space; (II) the dimensions of the tumor were quantitatively assessed, with the long diameter (LD) denoting the maximal length observed and the short diameter (SD) indicative of the maximal width perpendicular to the LD; (III) the enumeration of cardiac neoplasms was classified as either solitary or multiple; and (IV) pericardial effusion was registered as present or absent.

Combined nomogram model construction and assessment

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted by integrating indicators, including the Rad-score and NDIs, to select significant variables and construct a multivariate regression model. Variables demonstrating significance in the univariate analysis (P<0.05) were included in the multivariate analysis. Those that maintained significance in the multivariate context were identified as independent predictive factors. Utilizing these independent predictors, we developed a combined clinical-radiomic model and visualized it using a nomogram. To evaluate the model’s calibration capacity, calibration curves were plotted in both the training and validation sets to assess the model’s fit.

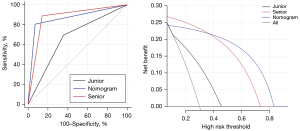

For a human-machine performance comparison, ROC curves and decision curve analysis (DCA) were employed to compare the discriminative efficacy and clinical utility of the combined model with those of two echocardiography physicians (one junior doctor with 2 years of echocardiographic diagnostic experience and one senior doctor with ten years of experience in echocardiographic diagnostics).

Statistical analysis

In the analysis of clinical baseline characteristics and echocardiographic features, continuous variables were evaluated for normality employing the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and intergroup comparisons were performed utilizing the independent samples t-test. Nonnormally distributed data were presented as the median with the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied for comparisons between groups. Categorical variables were depicted as percentages, and group comparisons were conducted using the Chi-squared (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test, contingent upon the data’s appropriateness for these tests. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics and subgroup of participants

In the screened cohort, a total of 121 individuals with verifiable histories of extracardiac malignancies were identified and enrolled for further comprehensive evaluation. All patients in this study underwent at least two different imaging modalities for evaluation, and 37 of them had surgical or biopsy pathology confirmation. Additionally, nine patients underwent PET/CT scans with specific high uptake of radiotracers to aid in the final malignant classification. CR (n=8) and PR (n=60) to chemotherapy combined with clinical evidence were classified as malignancy. Figure S1 provides an overview of the detailed classification and diagnostic pathways used in this study. The age range of the study population was from 21 to 71 years, with a median age of 56 years, and males constituted 59.5% (72 out of 121) of the participants. In the cohort, the lungs and liver were the primary sites of extracardiac malignant tumor involvement, constituting 25.6% and 22.3% of the patients, respectively. Moreover, a smaller proportion of cases involved glandular organs such as thymus, thyroid, and breast, each representing 3.3%. More details are depicted in the upper part of Table 1.

Table 1

| Variables | All | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristics# | |||

| Age (years) | 56 [48, 64] | 60 [53, 67] | 56 [45.5, 65] |

| Male | 72 (59.5) | 13 (50.0) | 59 (62.1) |

| Origin/etiology | |||

| Lung | 31 (25.6) | 6 (23.1) | 25 (26.3) |

| Liver | 27 (22.3) | 2 (7.7) | 25 (26.3) |

| Renal | 11 (9.1) | 3 (11.5) | 8 (8.4) |

| Sarcoma | 11 (9.1) | 1 (3.8) | 10 (10.5) |

| Lymphoma | 9 (7.4) | 0 | 9 (9.5) |

| Digestive system | 8 (6.6) | 4 (15.4) | 4 (4.2) |

| Thymus | 4 (3.3) | 0 | 4 (4.2) |

| Thyroid | 4 (3.3) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (2.1) |

| Breast | 4 (3.3) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (2.1) |

| Others* | 12 (9.9) | 6 (23.1) | 6 (6.3) |

| Echocardiographic findings# | |||

| Tumor location | |||

| LA | 36 (16.7) | 17 (40.5) | 19 (11.0) |

| LV | 20 (9.3) | 8 (19.1) | 12 (6.9) |

| RA | 70 (32.6) | 9 (21.4) | 61 (35.3) |

| RV | 32 (14.9) | 3 (7.1) | 29 (16.8) |

| VC | 32 (14.9) | 2 (4.8) | 30 (17.3) |

| PA | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Pericardium | 14 (6.5) | 3 (7.1) | 11 (6.4) |

| Myocardium | 9 (4.2) | 0 | 9 (5.2) |

| Tumor size (long dimension) | |||

| <20 mm | 23 (10.7) | 12 (28.6) | 11 (6.4) |

| 20–39 mm | 95 (44.2) | 14 (33.3) | 81 (46.8) |

| 40–59 mm | 49 (22.8) | 6 (14.3) | 43 (24.9) |

| 60–79 mm | 39 (18.1) | 10 (23.8) | 29 (16.8) |

| ≥80 mm | 9 (4.2) | 0 | 9 (5.2) |

| Solitary | 174 (80.9) | 40 (95.2) | 134 (77.5) |

| Effusion | 53 (24.7) | 7 (16.7) | 46 (26.6) |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR]. *, others: pancreas, blood, reproductive system, and brain; #, population characteristics sample size: all n=121, benign n=26, malignant n=95; echocardiographic findings sample size: all n=215, benign n=42, malignant n=173. Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; VC, vein cava; PA, pulmonary artery; IQR, interquartile range.

After excluding 27 clips due to poor quality, 215 echocardiographic clips were selected for model development. The detailed and gross echocardiographic findings of the enrolled cardiac tumors are listed in the lower part of Table 1. Among the 215 clips analyzed, 173 (80.5%) were categorized into the malignant group, and 42 were categorized into the benign group. Although a typical training-to-test ratio of 7:3 to 8:2 is commonly used in training and validation models, the limited number of benign tumor cases in our dataset posed a challenge for effective model training under these conventional splits. To address this, a larger proportion of the data were allocated to the training set to improve the model’s learning capacity, while still ensuring an adequate number of cases in the test set for validation. Ultimately, these clips were subsequently divided at random into a training dataset comprising 129 clips (28 benign and 101 malignant) and a test dataset of 86 clips comprising 14 benign and 72 malignant clips for facilitating model development and validation, respectively. In addition, comparisons of potential predictors between the training and test sets, as determined through statistical analysis, revealed no significant differences, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Variables | Training set (n=129) | Test set (n=86) | Statistic# | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 74 (57.4) | 46 (53.5) | 0.865 | >0.99 |

| Age (years) | 58 [43, 67] | 57 [43, 68] | 0.161 | 0.856 |

| Malignant | 101 (78.29) | 72 (83.72) | 0.967 | 0.326 |

| Localization (right cardiac circulatory) | 83 (64.34) | 56 (65.12) | 0.014 | 0.907 |

| Short dimension, mm | 27 [17, 34] | 28.5 [20.25, 32.75] | −0.737 | 0.461 |

| Rad-score | 0.07 [0.04, 0.2] | 0.07 [0.03, 0.13] | 1.593 | 0.144 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR]. #, for categorical variables, “Statistic” represents the Chi-squared test statistic. For non-normally distributed variables, “Statistic” represents the Z value from the Mann-Whitney U test. IQR, interquartile range; Rad-score, radiomics score.

Indicator analysis

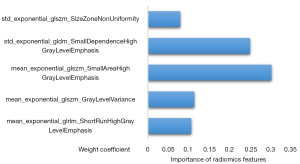

Out of the 1,878 radiomics and 4 motion features extracted, 30 features were selected as potential candidates for the development of classification frameworks. Ultimately, a refined framework with an AB classifier with 5 significant features and corresponding weightings was constructed, in which the features with varying weightings are depicted in Figure 2. Among these radiomics features, the mean_exponential_glszm_SmallAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis had the highest significant weight. The Rad-score, as a radiomic signature, was subsequently linearly calculated by significant features and weightings based on an optimal framework with a mean AUC of 0.76±0.04.

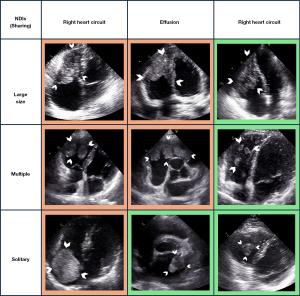

Notably, certain tumors, despite exhibiting identical echocardiographic NDIs, are classified differently as either benign or malignant. However, within the same classification of malignant or benign cardiac tumors, diverse combinations of NDIs were observed, indicating the challenge of tumor classification based on these indicators. Some typical cases are exemplified in Figure 3. Nevertheless, univariate analysis revealed significant differences in several NDIs between the benign and malignant cardiac tumor groups. Malignant tumors tended to have larger diameters, including both the long axis (mean: 38 vs. 24 mm, P=0.022) and the short axis (mean: 29 vs. 17 mm, P<0.001). Most malignant cardiac tumors were found to be located in the right side of the circulation (72.2% vs. 28.0%, P<0.001) and tended to occur in younger individuals (median age: 56 vs. 60 years, P=0.01) compared to benign cardiac tumors. The Rad-score, which primarily represents the histological texture characteristics, was significantly greater in benign cardiac tumor than in malignant one [median (interquartile range), 0.19 (0.04, 0.45) vs. 0.07 (0.03, 0.13), P<0.001].

Model construction and evaluation

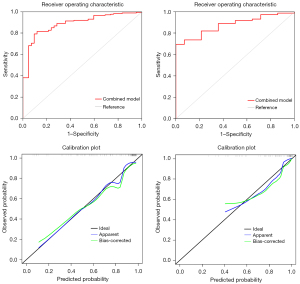

Subsequent multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that right circulatory localization (P<0.001), SD (P=0.002), and the Rad-score were independent predictors of malignancy, as detailed in Table 3. The constructed comprehensive model demonstrated robust classification performance with an AUC value of 0.873 and was effectively validated in the test cohort, achieving an AUC of 0.861, as shown in Table 4. The ROC curves and corresponding calibration curves for the models in both the training and test sets are depicted in Figure 4.

Table 3

| Variates | Training set (n=129) | Univariate analysis, P value |

Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign (n=28) | Malignant (n=101) | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Population characteristics | |||||

| Male | 13 (46.4) | 61 (60.4) | 0.109 | – | – |

| Age (years) | 60 [53, 67] | 56 [43, 63] | 0.01* | – | 0.115 |

| Location of cardiac tumors | |||||

| Left heart circulatory | 18 (64.3) | 21 (20.8) | 0.935 | – | – |

| Right heart circulatory | 8 (28.6) | 73 (72.3) | <0.001* | 0.17 (0.07,0.4) | <0.001* |

| Myocardium | 0 | 4 (4.0) | 0.987 | – | – |

| Pericardium | 2 (7.1) | 3 (3.0) | – | – | – |

| Tumor size | |||||

| Long dimension of cardiac tumor (mm) | 24 [19, 54] | 38 [30, 53] | 0.022* | – | 0.0522 |

| Short dimension of cardiac tumor (mm) | 17 [12, 29.5] | 29 [21, 34] | <0.001* | 1.07 (1.02–1.11) | 0.002* |

| Number of tumor (solitary) | 28 (100.0) | 78 (77.2) | 0.987 | – | – |

| Effusion | 4 (14.3) | 28 (27.7) | 0.185 | 2.52 (0.87–7.32) | 0.0871 |

| Rad-score | 0.19 [0.04, 0.45] | 0.07 [0.03, 0.13] | <0.001* | 0.03 (0.02–0.87) | <0.001* |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR]. *, denotes statistical significance. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Rad-score, radiomics score; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 4

| Models | Set group | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive | Training | 0.873 (0.820–0.914) | 0.988 | 0.501 | 0.887 |

| Test | 0.861 (0.807–0.904) | 0.960 | 0.405 | 0.851 | |

| Nomogram | Test | 0.867 (0.777–0.931) | 0.983 | 0.520 | 0.826 |

| Junior | Test | 0.669 (0.559–0.766) | 0.909 | 0.290 | 0.686 |

| Senior | Test | 0.873 (0.784–0.935) | 0.970 | 0.600 | 0.883 |

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

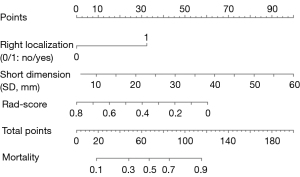

A final nomogram developed using independent indicators, including right circulatory localization, SD, and Rad-score, is depicted in Figure 5. The nomogram functions as a cumulative scoring system to estimate the likelihood of a lesion being malignant. An ROC curve analysis was performed, and the optimal cutoff score was calculated to be 0.82, which provided the best balance between sensitivity of 98.3% and a specificity of 52.0% in differentiating between benign and malignant lesions. This cutoff allows for a practical and efficient application of the nomogram in clinical settings, enabling physicians to make informed decisions regarding the nature of cardiac lesions. Moreover, its performance was comparable to that of senior physicians (AUC: 0.867 vs. 0.873, DeLong’s test P=0.928), and it outperformed junior physicians (AUC: 0.867 vs. 0.669, DeLong’s test P=0.029) in the test set. The prediction of binary classification outcomes—benign vs. malignant—derived from nomogram prediction probabilities and seniority assessments (senior vs. junior) with actual diagnostic classifications were depicted through ROC and DCA curves, as shown in Figure 6. The DCA curves demonstrated that the nomogram enhanced clinical utility over the junior physician for classification tasks, with the threshold probability for clinicians or patients being between approximately 10% and 40%.

Discussion

In this preliminary study, we innovatively integrated objective indicators, including patient baselines and gross echocardiographic characteristics of cardiac tumors, with the Rad-score, which captures textural features of tumors, to enhance the practicality and depth of our cardiac tumor classification model. This integration not only increases diagnostic confidence but also addresses a significant clinical need by providing a detailed and nuanced complement to traditional echocardiographic methods. To streamline the classification process, our model utilizes echocardiogram-derived radiomics, aiming to aid less experienced clinicians in accurately classifying cardiac tumors. This approach seeks to reduce the reliance on advanced, expensive, and invasive diagnostic procedures, offering a more efficient and accessible pathway for patient assessment and management. The principal findings of our study are summarized as follows: (I) a radiomics-based Rad-score was successfully obtained through a series of ML methods applied to echocardiographic clips, providing potential for classifying cardiac tumors. (II) Certain features exhibited significant differences between the two groups whereas some overlapping gross characteristics were observed in the echocardiograms of benign and malignant cardiac tumors. (III) A comprehensive model that integrates the Rad-score with NDIs demonstrated a robust capacity to discriminate between benign and malignant cardiac tumors. Furthermore, the final nomogram exhibited diagnostic effectiveness in classifying individuals, with a performance superior to that of junior sonographers.

In our diagnostic practice, baseline clinical and echocardiographic findings are pivotal for classifying cardiac tumors, yet they often lack specificity (2). Certain imaging features, such as infiltration, pericardial effusion, polylobate shape, sessile growth, inhomogeneity, and non-left localization, are associated with malignancies (17). However, the accurate interpretation of these features is highly dependent on the observer’s expertise, which is challenged by the rarity of cardiac tumors and potential assessment biases. Our study prioritized indicators less influenced by experience, such as tumor location, size, number, and the presence of effusion, which can be reliably assessed by novices. Overlapping gross characteristics were observed between benign and malignant cardiac tumors on echocardiograms, although specific features demonstrated notable potential for differentiation. In cancer patients, tumor characteristics, including size and effusion, are influenced not only by tumor nature but also by external factors such as cachexia and anticancer treatments. This may account for the lack of significant differences between the malignant and benign groups in our analysis. Malignant tumors tend to exhibit larger dimensions, particularly in their SDs, reflecting greater volume and a plumper shape. Nonetheless, certain benign tumors, such as myxomas, can grow significantly large, sometimes occupying both atrial and ventricular spaces (25). Tumor localization further aids malignancy identification, for example, right-sided cardiac involvement often corresponds to liver or kidney malignancies via the inferior vena cava, whereas the left atrium may serve as a metastatic site for central lung neoplasms via the pulmonary veins (10). In contrast, most benign tumors, such as myxomas, are predominantly located in the left atrium (3). Although solitary tumors are common in both benign and malignant cases, our study observed multiple masses in some instances, including leiomyomas and lymphomas. Overall, our findings underscore the necessity for supplementary diagnostic evidence to address the limitations of conventional gross feature-based diagnostic approaches.

Before this work, the “Rad-score” had been highlighted for its diagnostic potential across various organs using multiple imaging modalities, including US (26-28). The application of ML to echocardiography has garnered increasing attention, leading to notable developments such as Penatti et al.’s efficient real-time cardiac US classification (29), Zamzmi et al.’s advancements in echo view retrieval and cardiac segmentation (30), and automated models for assessing cardiac structure and function, which are useful for identifying conditions such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and pulmonary hypertension (31). These innovations have significantly improved the accuracy and ease of disease diagnosis, propelled by the rapid evolution of ML. Radiomics, which emphasizes the analysis of grayscale levels, heterogeneity, and distribution patterns, aims to quantitatively describe phenotypic characteristics in medical imaging through automated algorithms (24). In our study, the first ML attempt in patients with infrequent cardiac tumors posed significant challenges due to the limited and unevenly distributed data. To address these hurdles, we employed several strategies. First, we fine-tuned the decision threshold to achieve an optimal balance between accuracy and sensitivity, thereby enhancing the model’s performance. Subsequently, we utilized the scikit-learn library to perform an exhaustive grid search, investigating various combinations of feature selection methods and classifiers. Additionally, a rigorous 4-fold cross-validation method was employed for evaluation. Ultimately, this process generated a Rad-score based on grayscale features such as uniformity, diversity, and intensity, effectively capturing lesion textures and reflecting microscopic pathological differences between malignant and benign cardiac tumors. As a noninvasive imaging-based biomarker, the Rad-score demonstrated robust performance in distinguishing between tumor types, underscoring the potential of advanced radiomics in improving diagnostic precision. These radiomic features likely correspond to key pathological traits, including microvascular density, interstitial variations, and cancer cell pleomorphism—characteristics that are shared across malignancies regardless of their primary organ origin or stage. By addressing the overlapping features inherent in traditional echocardiographic assessments, the Rad-score provides a more nuanced and comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, comparisons between senior and junior physicians in our study underscore the utility of the radiomics-based model in enhancing diagnostic accuracy across varying levels of experience. Although the model’s diagnostic capacity was on par with that of senior physicians, its ability to support junior physicians by reducing variability and boosting diagnostic confidence highlights its broad applicability and potential for integration into clinical practice.

The dynamic characteristics of cardiac tumors throughout the cardiac cycle provide valuable insights into their thorough evaluation and differentiation of subtypes in routine clinical practice (2). These dynamics are influenced by factors such as tumor size, location, and implantation site. Intriguingly, our study revealed that the mobility features of cardiac tumors, as captured through the optimal flow method, did not markedly enhance the classification task. This finding opens avenues for future research focused on the development of innovative and appropriate motion-extraction techniques, especially those utilizing 3-dimensional (3D) data, aiming to improve our classification capabilities and understanding in this domain.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the rarity and uneven distribution of cardiac tumors limited the sample size, focusing mainly on distinguishing malignant and benign lesions, without addressing more detailed pathological subcategories such as thrombi or tumor stages. Additionally, conducted at a single center, external validation using multicenter datasets is needed to assess generalizability. Second, although we have applied rigorous methods, we acknowledge that relying on multimodal imaging and clinical evidence as surrogates for histopathological gold standards may introduce some degree of subjectivity. Third, although the radiomics-based nomogram demonstrated significant potential, its application in clinical practice may be limited by the need for specialized software, computational resources, and expertise in radiomics analysis, posing challenges for widespread implementation. Last, it is pivotal to recognize that the prognosis of patients is influenced by the characteristics of cardiac tumors beyond their malignant nature, such as localization, myocardial infiltration, stability, and other imaging findings. Future studies should aim to incorporate these additional indicators into a more holistic prognostic model for individuals with cardiac tumors.

Conclusions

This study successfully developed a comprehensive nomogram integrating the Rad-score based on radiomics with nonexperience-dependent indicators derived from baseline characteristics and echocardiographic findings. This noninvasive model effectively differentiated between malignant and benign cardiac tumors, enhancing the use of traditional methodologies. Designed to streamline the tumor classification process, this model is especially beneficial in medical settings where clinicians may have varying levels of experience, thereby advancing the quality of healthcare decision-making.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1096/rc

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1096/coif). D.W. is a current employee of Jinan Kangshouxin (KSX) Healthcare Ltd. Co. The company had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or decision to publish the manuscript. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital (No. TJ-IRB20210227) and the need to obtain written informed consent from all patients was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Tyebally S, Chen D, Bhattacharyya S, Mughrabi A, Hussain Z, Manisty C, Westwood M, Ghosh AK, Guha A. Cardiac Tumors: JACC CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol 2020;2:293-311. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Angeli F, Fabrizio M, Paolisso P, Magnani I, Bergamaschi L, Bartoli L, Stefanizzi A, Armillotta M, Sansonetti A, Amicone S, Impellizzeri A, Tattilo FP, Suma N, Bodega F, Canton L, Rinaldi A, Foà A, Pizzi C. Cardiac masses: classification, clinical features and diagnostic approach. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2022;23:620-30. [PubMed]

- Cresti A, Chiavarelli M, Glauber M, Tanganelli P, Scalese M, Cesareo F, Guerrini F, Capati E, Focardi M, Severi S. Incidence rate of primary cardiac tumors: a 14-year population study. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2016;17:37-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:219-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalra MK, Abbara S. Imaging cardiac tumors. Cancer Treat Res 2008;143:177-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013;128:1790-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bussani R, De-Giorgio F, Abbate A, Silvestri F. Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:27-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palaskas N, Thompson K, Gladish G, Agha AM, Hassan S, Iliescu C, Kim P, Durand JB, Lopez-Mattei JC. Evaluation and Management of Cardiac Tumors. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2018;20:29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mao YH, Deng YB, Liu YN, Wei X, Bi XJ, Tang QY, Wang YB, Wang XY. Contrast Echocardiographic Perfusion Imaging in Clinical Decision-Making for Cardiac Masses in Patients With a History of Extracardiac Malignant Tumor. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:754-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Griborio-Guzman AG, Aseyev OI, Shah H, Sadreddini M. Cardiac myxomas: clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Heart 2022;108:827-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Angeli F, Bergamaschi L, Paolisso P, Armillotta M, Sansonetti A, Stefanizzi A, et al. Spectrum of electrocardiographic abnormalities in a large cohort of cardiac masses. Heart Rhythm 2025;22:240-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foà A, Paolisso P, Bergamaschi L, Rucci P, Di Marco L, Pacini D, Leone O, Galié N, Pizzi C. Clues and pitfalls in the diagnostic approach to cardiac masses: are pseudo-tumours truly benign? Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022;29:e102-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shenoy C, Grizzard JD, Shah DJ, Kassi M, Reardon MJ, Zagurovskaya M, Kim HW, Parker MA, Kim RJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in suspected cardiac tumour: a multicentre outcomes study. Eur Heart J 2021;43:71-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paolisso P, Bergamaschi L, Angeli F, Belmonte M, Foà A, Canton L, et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance to Predict Cardiac Mass Malignancy: The CMR Mass Score. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2024;17:e016115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lichtenberger JP 3rd, Carter BW, Pavio MA, Biko DM. Cardiac Neoplasms: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiol Clin North Am 2021;59:231-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paolisso P, Foà A, Bergamaschi L, Graziosi M, Rinaldi A, Magnani I, et al. Echocardiographic Markers in the Diagnosis of Cardiac Masses. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2023;36:464-473.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lambin P, Rios-Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, Carvalho S, van Stiphout RG, Granton P, Zegers CM, Gillies R, Boellard R, Dekker A, Aerts HJ. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:441-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016;278:563-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu T, Zhou S, Yu J, Guo Y, Wang Y, Zhou J, Chang C. Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients With Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Radiomics Method Based on Preoperative Ultrasound Images. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2019;18:1533033819831713. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luo WQ, Huang QX, Huang XW, Hu HT, Zeng FQ, Wang W. Predicting Breast Cancer in Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) Ultrasound Category 4 or 5 Lesions: A Nomogram Combining Radiomics and BI-RADS. Sci Rep 2019;9:11921. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng JB, Peng YT, Lin P, Wan D, Qin H, Li X, Wang XR, He Y, Yang H. Differentiating infected focal liver lesions from malignant mimickers: value of ultrasound-based radiomics. Clin Radiol 2022;77:104-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li C, Qiao G, Li J, Qi L, Wei X, Zhang T, Li X, Deng S, Wei X, Ma W. An Ultrasonic-Based Radiomics Nomogram for Distinguishing Between Benign and Malignant Solid Renal Masses. Front Oncol 2022;12:847805. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Griethuysen JJM, Fedorov A, Parmar C, Hosny A, Aucoin N, Narayan V, Beets-Tan RGH, Fillion-Robin JC, Pieper S, Aerts HJWL. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res 2017;77:e104-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grebenc ML, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Green CE, Burke AP, Galvin JR. Cardiac myxoma: imaging features in 83 patients. Radiographics 2002;22:673-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Q, Jiang T, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Huang Z, Zhou H, Huang P. A nomogram based on clinical information, conventional ultrasound and radiomics improves prediction of malignant parotid gland lesions. Cancer Lett 2022;527:107-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu A, Liu B, Duan X, Yang B, Wang Y, Dong P, Zhou P. Development of a novel combined nomogram model integrating Rad-score, age and ECOG to predict the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. J Gastrointest Oncol 2022;13:1889-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng YM, Li J, Liu S, Cui JF, Zhan JF, Pang J, Zhou RZ, Li XL, Dong C. MRI-Based radiomics nomogram for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions of the parotid gland. Eur Radiol 2021;31:4042-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penatti OA, Werneck Rde O, de Almeida WR, Stein BV, Pazinato DV, Mendes Júnior PR, Torres Rda S, Rocha A. Mid-level image representations for real-time heart view plane classification of echocardiograms. Comput Biol Med 2015;66:66-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zamzmi G, Rajaraman S, Hsu LY, Sachdev V, Antani S. Real-time echocardiography image analysis and quantification of cardiac indices. Med Image Anal 2022;80:102438. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Gajjala S, Agrawal P, Tison GH, Hallock LA, Beussink-Nelson L, Lassen MH, Fan E, Aras MA, Jordan C, Fleischmann KE, Melisko M, Qasim A, Shah SJ, Bajcsy R, Deo RC. Fully Automated Echocardiogram Interpretation in Clinical Practice. Circulation 2018;138:1623-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]