Incremental prognostic value of computed tomography-determined mitral annular dilatation in patients with severe aortic regurgitation undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a retrospective cohort study

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is not only an essential therapeutic option for symptomatic aortic stenosis (1-3), but with the advancement of TAVR as a mature and safe procedure, particularly with the development of new transcatheter heart valves for aortic regurgitation (AR), TAVR has been progressively applied to patients with symptomatic severe AR (4-6). Concomitant moderate or severe mitral regurgitation (MR) is not uncommon in patients with hemodynamically significant AR, and has a worse prognosis than AR alone (7,8). Mitral annular dilatation (MAD) has been shown to be associated with MR (9-11). However, previous studies have primarily focused on the effect of MR on the prognosis of patients following TAVR (12-14), and insufficient attention has been paid to the relationship between MAD and TAVR outcomes.

Currently, cardiac computed tomography (CT) is a prerequisite for TAVR procedure planning, and is used to determine prosthesis size and procedure access (15). CT is of great value in assessing the valvular anatomy, as it can be used in the objective and highly reproducible assessment of the mitral annulus (16). This study aimed to investigate the prognosis value of MAD determined by CT in patients with severe AR undergoing TAVR. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1608/rc).

Methods

Study design and population

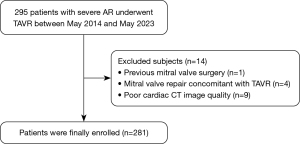

This retrospective cohort study included consecutive patients with severe AR who underwent TAVR at Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University from May 2014 to May 2023. All patients were evaluated by the local heart team and deemed suitable candidates for TAVR. Patients with a history of mitral valve surgery, as well as those who underwent transcatheter mitral valve repair concurrently with TAVR, were excluded from the study. Additionally, patients with poor-quality cardiac CT images were also excluded from the study. A flowchart outlining the patient selection process for this study is shown in Figure 1.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University (No. B2023-005R), and the requirement of individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Assessment of the D-shaped mitral annulus

Cardiac CT was obtained using first-, second-, or third-generation dual-source CT scanners (Siemens Healthineers, Erlagen, Germany). To enhance contrast, 60–80 mL of contrast agent (370 mg iodine/mL, Ultravist, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) was injected through the antecubital vein at a rate of 4 mL/s, followed by 40 mL of saline injected at the same rate (as per the biphasic injection protocol). Retrospective electrocardiogram-gated acquisition was performed to cover the entire cardiac cycle. The tube voltage and current were adjusted based on body size. The scanning range extended from the carina to the diaphragm, with axial images reconstructed at 10% intervals of the cardiac cycle, and a slice thickness of 0.625 mm.

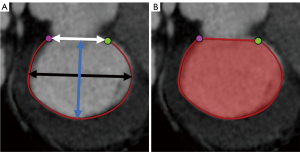

Measurements of the mitral annulus were conducted at end-systole as previously described (17), using a dedicated valve analysis workstation (3mensio Structural Heart version 7.0, Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, Netherlands) as shown in Figure 2. The annular anteroposterior, intercommissural, and trigone-to-trigone distances, as well as the mitral annulus area and perimeter, were measured.

Echocardiographic analysis

Transthoracic echocardiography was routinely performed before the TAVR procedure by experienced echocardiographers with more than 10 years of experience. MR was classified as no/trivial, mild, moderate, or severe using a comprehensive multiparametric approach, including qualitative, semiquantitative, and quantitative measures in accordance with current recommendations (18). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated using the biplane Simpson’s method (19). Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) was measured in accordance with the guidelines (19). Specifically, the peak velocity of the tricuspid regurgitant (TR) jet was measured by continuous wave Doppler echocardiography. Right atrial pressure was estimated based on the size and collapsibility of the inferior vena cava. PASP was then estimated based on the simplified Bernoulli equation, which was expressed as follows: PASP = 4 × (TR velocity)2 + estimated right atrial pressure. Pulmonary hypertension was defined as PASP >40 mmHg. TR was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe, and right ventricular systolic function was evaluated using tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) as recommended by the current guidelines (19).

Study outcomes

The clinical endpoint of this study was the composite outcome of all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization following TAVR. Clinical follow-up was conducted either by telephone interviews, medical records, or outpatient clinic visits at 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years. The time to the clinical endpoint was calculated as the time to the first event of death or heart-failure hospitalization after TAVR.

Statistical analysis

The normal distribution of continuous parameters was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and were compared using the Student t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous are presented as the median with the interquartile range (IQR), and were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as the number with the percentage, and were compared using the Chi-squared test, continuity-corrected Chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test.

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to determine the optimal body surface area standardized cut-off value for MAD, and the cut-off value was taken at the maximal Youden index to best predict the clinical endpoint. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between groups were performed using the log-rank test. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were applied to determine significant predictors of the composite outcome. A multivariate analysis was performed using an iterative method of stepwise-backward regression for all variables with P values <0.05 (two-sided) in the univariate analysis. The proportional hazard assumptions were verified using the Schoenfeld residuals test. Estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Nested models were built to evaluate the incremental prognostic value of CT-determined MAD by calculating the net reclassification improvement and the integrated discrimination improvement. Goodness-of-fit statistics were calculated using the Chi-squared test and Akaike information criterion. The performance of the model was assessed using the concordance index.

To test intra- and inter-observer variability of the measurements on CT, 20 randomly selected patients were investigated repeatedly by one experienced observer at two different time points, and by another experienced observer. Reproducibility was evaluated by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.5.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 295 patients with severe AR who underwent TAVR at Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University between May 2014 and May 2023, 14 were excluded due to a history of mitral valve surgery (n=1), receipt of transcatheter mitral valve repair concurrently with TAVR (n=4), and poor image quality (n=9). Thus, a total of 281 patients [mean age: 72.6±7.5 years; 93 (33.1%) female] were included in the final analysis (Table 1). Of the patients, 26.3% had a history of coronary artery disease. The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation was 3.6% (IQR, 2.0–6.4%). The mean LVEF was 53.1%±12.1%. Of the patients, 30.6% had moderate or severe MR.

Table 1

| Variables | All patients (n=281) | Without composite outcomes (n=240) | With composite outcomes (n=41) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.6±7.5 | 72.7±7.0 | 71.9±9.8 | 0.632 |

| Female | 93 (33.1) | 80 (33.3) | 13 (31.7) | 0.838 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.0±3.3 | 23.2±3.2 | 21.9±4.0 | 0.026 |

| Hypertension | 186 (66.2) | 157 (65.4) | 29 (70.7) | 0.506 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (14.2) | 31 (12.9) | 9 (22.0) | 0.126 |

| COPD | 67 (23.8) | 49 (20.4) | 18 (43.9) | 0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 63.7±20.5 | 64.9±19.6 | 56.6±24.3 | 0.043 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 114 (40.6) | 91 (37.9) | 23 (56.1) | 0.028 |

| Liver disease | 4 (1.4) | 4 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 64 (22.8) | 52 (21.7) | 12 (29.3) | 0.283 |

| Prior cerebrovascular accident | 49 (17.4) | 42 (17.5) | 7 (17.1) | 0.947 |

| Coronary artery disease | 74 (26.3) | 65 (27.1) | 9 (22.0) | 0.490 |

| Prior PCI | 28 (10.0) | 24 (10.0) | 4 (9.8) | >0.99 |

| Prior CABG | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 9 (3.2) | 6 (2.5) | 3 (7.3) | 0.255 |

| Presence of pacemaker or ICD | 6 (2.1) | 6 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.597 |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 16 (5.7) | 16 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.181 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 45 (16.0) | 34 (14.2) | 11 (26.8) | 0.041 |

| EuroSCORE II (%) | 3.6 (2.0–6.4) | 3.4 (1.9–5.6) | 6.8 (4.2–13.6) | <0.001 |

| NYHA class > II | 234 (83.8) | 195 (81.3) | 39 (95.1) | 0.028 |

| Potential mechanisms of AR | 0.277 | |||

| Valve leaflet degeneration or prolapse | 42 (14.9) | 37 (15.4) | 5 (12.2) | |

| Dilated aortic sinuses or ascending aorta | 154 (54.8) | 136 (56.7) | 18 (43.9) | |

| Coexistence of leaflet and annulus lesions | 47 (16.7) | 37 (15.4) | 10 (24.4) | |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 25 (8.9) | 21 (8.8) | 4 (9.8) | |

| Previous infective endocarditis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Takayasu arteritis | 13 (4.6) | 9 (3.8) | 4 (9.8) | |

| Echocardiographic findings | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 53.1±12.1 | 54.2±11.6 | 46.4±13.0 | <0.001 |

| PASP >40 mmHg | 102 (36.3) | 75 (31.3) | 27 (65.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥ Moderate MR | 86 (30.6) | 63 (26.3) | 23 (56.1) | <0.001 |

| ≥ Moderate TR | 36 (12.8) | 23 (9.6) | 13 (31.7) | <0.001 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 25 (8.9) | 21 (8.8) | 4 (9.8) | >0.99 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 44.2±6.6 | 43.7±6.3 | 47.5±7.4 | <0.001 |

| TAPSE <16 mm | 7 (2.5) | 5 (2.1) | 2 (4.9) | 0.604 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (IQR). BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; NYHA, New York Heart Association; AR, aortic regurgitation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; MR, mitral regurgitation; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Throughout the median follow-up period of 2.0 years (IQR, 1.1–2.5 years), the composite outcome was observed in 41 patients (cumulative event rate: 14.6%). Of these 41 patients, 21 experienced all-cause death, 8 experienced heart-failure hospitalization, and 12 experienced both events. A comparison of the clinical baseline characteristics of the patients with and without the composite outcome is shown in Table 1.

Mitral annulus evaluation on CT

All mitral annular CT characteristics of the entire study cohort are shown in Table 2. In the study cohort, the median body surface area standardized annulus perimeter and area were 70.7 mm/m2 (IQR, 65.6–77.0 mm/m2) and 5.7 cm2/m2 (IQR, 5.0–6.6 cm2/m2), respectively. The intra- and inter-observer agreement was excellent, with the intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.91 to 0.98 (Table S1). Perimeter was the strongest predictor of the composite outcome among all measured mitral annular parameters, including area, trigone-to-trigone, anteroposterior, and intercommissural distances (Table S2). Based on the ROC curve analysis, the optimal body surface area standardized cut-off value for MAD that was identified as being associated with an increased composite outcome was 71.3 mm/m2. Based on this threshold, MAD was identified in 132 (47.0%) patients. The baseline characteristics of patients stratified by the presence or absence of MAD are shown in Table S3.

Table 2

| Variables | Total (n=281) |

|---|---|

| Trigone-to-trigon distance (mm/m2) | 17.4 (15.7–19.3) |

| Intercommisural distance (mm/m2) | 24.2 (22.2–26.4) |

| Anteroposterior distance (mm/m2) | 17.4 (15.7–19.3) |

| Annulus area (cm2/m2) | 5.7 (5.0–6.6) |

| Annulus perimeter (mm/m2) | 70.7 (65.6–77.0) |

| Mitral annular calcification | 11 (3.9) |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or n (%). IQR, interquartile range.

Association between MAD and outcomes

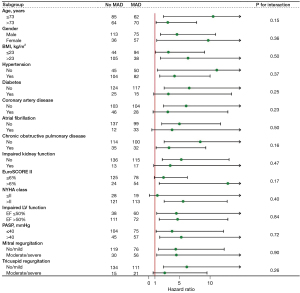

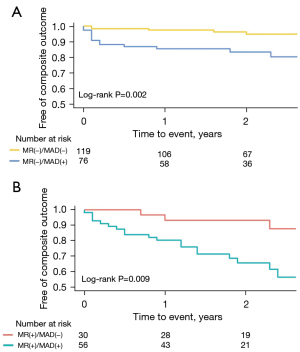

The patients with MAD had significantly lower survival rates for the composite outcome than those without MAD (log-rank P<0.001). The estimated 1- and 2-year survival rates without the composite outcome were 83.3% (95% CI: 77.1–89.9%) and 75.6% (95% CI: 68.1–84.0%) for patients with MAD and 96.6% (95% CI: 93.6–99.6%) and 94.5% (95% CI: 90.5–98.6%) for patients without MAD, respectively. The survival curves are shown in Figure 3. Patients with MAD also had significantly lower survival rates for all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization (log-rank P<0.001; Figure S1). The prognostic value of MAD was consistent across the clinically relevant subgroups, with no significant interaction p values observed in any of the studied subgroups (Figure 4). It should be noted that there were no statistically significant differences in the procedural characteristics of patients with and without MAD (Table 3). In addition, MAD was not found to have any effect on in-hospital adverse events.

Table 3

| Variables | All patients (n=281) | No MAD (n=149) | MAD (n=132) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosthesis size (mm) | 0.794 | |||

| <25 | 13 (4.6) | 6 (4.0) | 7 (5.3) | |

| 25–28 | 144 (51.2) | 75 (50.3) | 69 (52.3) | |

| >28 | 124 (44.1) | 68 (45.6) | 56 (42.4) | |

| Prosthesis type | 0.390 | |||

| J-Valve TF | 28 (10.0) | 17 (11.4) | 11 (8.3) | |

| J-Valve TA | 253 (90.0) | 132 (88.6) | 121 (91.7) | |

| Pre-dilatation performed | 3 (1.1) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.290 |

| Post-dilatation performed | 47 (16.7) | 28 (18.8) | 19 (14.4) | 0.324 |

| Valve-related complications | ||||

| Valve migration | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 0.916 |

| Moderate or severe paravalvular leakage | 4 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.3) | 0.535 |

| All-cause mortality | 5 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.8) | 0.052 |

| Stroke | 49 (17.4) | 29 (19.5) | 20 (15.2) | 0.342 |

| Permanent pacemaker implantation | 14 (5.0) | 6 (4.0) | 8 (6.1) | 0.434 |

Data are presented as n (%). MAD, mitral annular dilatation; TF, transfemoral; TA, transapical.

Incremental prognostic value of MAD

Besides MAD, the univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that the body mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, LVEF, left atrial diameter, New York Heart Association functional class III or IV, atrial fibrillation, presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, presence of moderate or severe MR, presence of moderate or severe tricuspid regurgitation, and elevated PASP were significant parameters for the composite outcome (Table 4). Nested models were constructed to evaluate the incremental prognostic value of MAD. The baseline model (Model 1) comprised clinical and echocardiographic parameters, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LVEF, moderate or severe MR, and elevated PASP. Model 2 was built by adding MAD to Model 1. In multivariable Model 2, MAD remained associated with the risk of the composite outcome. MAD was the strongest independent predictor of the composite outcome (adjusted HR: 4.07; 95% CI: 1.85–8.99; P=0.001). The addition of MAD to conventional clinical and echocardiographic risk factors improved the model fit and discrimination for the composite outcome (Table 5). When comparing the two models, the incremental predictive value of MAD showed a net reclassification improvement of 0.40 (95% CI: 0.21–0.54; P=0.01) and an integrated discrimination improvement of 0.06 (95% CI: 0.01–0.14; P=0.02).

Table 4

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate without MAD (Model 1) | Multivariate with MAD (Model 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 0.401 | ||||||

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.89 (0.80–0.98) | 0.020 | ||||||

| Female | 0.93 (0.48–1.79) | 0.819 | ||||||

| Hypertension | 1.11 (0.57–2.19) | 0.756 | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.83 (0.87–3.83) | 0.112 | ||||||

| COPD | 2.43 (1.31–4.51) | 0.005 | 2.26 (1.21–4.23) | 0.010 | 2.42 (1.29–4.54) | 0.006 | ||

| eGFR (per 10 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.84 (0.72–0.97) | 0.018 | ||||||

| Prior cerebrovascular accident | 1.11 (0.49–2.51) | 0.804 | ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 0.82 (0.39–1.72) | 0.601 | ||||||

| Prior cardiac surgery | 0.05 (0.00–15.29) | 0.298 | ||||||

| NYHA > II | 4.50 (1.09–18.66) | 0.038 | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.10 (1.05–4.20) | 0.035 | ||||||

| LVEF (per 5%) | 0.79 (0.69–0.89) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) | 0.057 | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) | 0.112 | ||

| PASP >40 mmHg | 3.54 (1.85–6.77) | <0.001 | 2.71 (1.37–5.33) | 0.004 | 2.72 (1.38–5.34) | 0.004 | ||

| ≥ Moderate MR | 2.89 (1.56–5.38) | 0.001 | 1.71 (0.86–3.41) | 0.127 | 1.35 (0.67–2.73) | 0.406 | ||

| ≥ Moderate TR | 3.34 (1.72–6.51) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Left atrial diameter (per 5 mm) | 1.48 (1.20–1.83) | <0.001 | ||||||

| TAPSE <16 mm | 3.04 (0.73–12.7) | 0.128 | ||||||

| Mitral annular calcification | 0.73 (0.27–1.97) | 0.535 | ||||||

| MAD | 5.14 (2.37–11.17) | <0.001 | 4.07 (1.85–8.99) | 0.001 | ||||

MAD, mitral annular dilatation; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NYHA, New York Heart Association; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; MR, mitral regurgitation; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Table 5

| Parameters | Multivariate without MAD (Model 1) |

Multivariate with MAD (Model 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Model fit statistics | ||

| Global Chi-squared test | 32.9 | 47.8 |

| AIC | 408.5 | 395.6 |

| Model performance | ||

| Concordance index (95% CI) | 0.74 (0.70–0.79) | 0.79 (0.75–0.82) |

| NRI (95% CI) | – | 0.40 (0.21–0.54) |

| IDI (95% CI) | – | 0.06 (0.01–0.14) |

Model 1 variates are COPD, LVEF, PASP >40 mmHg and ≥ moderate MR. Model 2 adds MAD to Model 1. MAD, mitral annular dilatation; AIC, Akaike information criterion; CI, confidence interval; NRI, net reclassification index; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; MR, mitral regurgitation.

MAD was present in 74.6% of patients with moderate or severe MR. Patients with MAD had an increased likelihood of the composite outcome regardless of the presence or absence of moderate or severe MR [HRs of 2.97 (95% CI: 1.06–8.32) and 2.48 (95% CI: 1.44–4.25), respectively]. The survival curves are shown in Figure 5. Notably, moderate or severe MR based on echocardiographic assessment was not an independent predictor of the composite outcome in either Model 1 or Model 2.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the association between CT-determined MAD and the risk of the composite outcome of all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization in patients with symptomatic severe AR undergoing TAVR. We found that MAD was a strong and independent predictor of all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization (multivariable HR: 4.07; 95% CI: 1.85–8.99; P=0.001). More importantly, MAD provided incremental utility beyond the clinical and echocardiographic risk assessment [net reclassification improvement: 0.40 (95% CI: 0.21–0.54), P=0.01; integrated discrimination improvement: 0.06 (95% CI: 0.01–0.14), P=0.02]. Notably, nearly half of the patients were found to have MAD, and the CT assessment of MAD was found to be convenient and highly reproducible, highlighting the clinical importance of this imaging biomarker.

Echocardiography is commonly used to evaluate mitral anatomy. However, the accurate and objective assessment of mitral annulus using echocardiography is challenging due to its operator- and acoustic window-dependence, and the complexity of the mitral annulus. CT has advantages over echocardiography in the assessment of the mitral annulus (16). In addition, CT has been established as a standard procedure for TAVR. Thus, the assessment of MAD with CT does not result in patient exposure to additional radiation or additional contrast media.

There are conflicting results in the literature as to the effects of moderate or severe MR on the prognosis of TAVR in patients with aortic stenosis. Some studies have identified moderate or severe MR as an independent predictor of higher all-cause death or heart-failure hospitalization, while others have found that moderate or severe MR had no significant effect on outcomes after TAVR (13,14,20,21). In the univariate analysis of this study, moderate or severe MR was a risk factor for increased all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization in patients with AR undergoing TAVR. However, moderate or severe MR was not statistically significant in the multivariable models. In contrast, MAD exhibited the highest HR in the multivariate analysis. Further, the model that included MAD demonstrated improved risk prediction for all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization compared to the multivariate model that did not include MAD. We further evaluated the prognostic value of MAD in patients stratified by the presence of moderate or severe MR. We found that patients with MAD experienced an increased risk of all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization, regardless of the presence of moderate or severe MR. This suggests that MAD could affect prognosis independently of MR. One possible explanation could be that while MAD is closely associated with MR, with the two often coexisting and reinforcing each other, MAD can be present in the absence of MR, as shown in this study. Studies have shown the enormous capacity of the mitral valve leaflets for remodeling (22,23). If the increased leaflet length still allows sufficient coaptation in the presence of MAD, MR will not be evident. Additionally, MAD attributed to atrial fibrillation may precede LV dysfunction and LV malignant remodeling characterized by significant decompensated LV dilatation and LV mass increase (24), contributing to worse outcomes independently of MR.

The effect of MAD on the prognosis of TAVR has not been directly investigated, particularly in patients with AR. However, in patients with aortic stenosis, Cortés et al. found that MAD was an independent and strong predictor of persistent MR after TAVR, and further revealed that persistent moderate or greater MR was associated with increased 6-month mortality after TAVR (25). Although their findings cannot be compared directly to those of the present study due to the differences in the underlying aortic valve disease, they highlight the importance of MAD in predicting the prognosis of TAVR. To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to directly explore the association between MAD and the prognosis of TAVR in patients with AR. This study found that MAD was present in nearly half of the patients with AR undergoing TAVR and was independently associated with the risk of all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization. Therefore, the preoperative assessment of MAD is important in patients with AR undergoing TAVR. Patients with MAD should be closely monitored after discharge, and should receive guideline-directed pharmacological treatment for heart failure or transcatheter mitral valve intervention as recommended by the local heart team. Further research is required to determine the optimal clinical and therapeutic management of patients with MAD undergoing TAVR.

Study limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective, single-center study with possible selection bias; thus, further multi-center, large-scale studies need to be conducted to confirm the results of this study. Second, the cut-off value for MAD was obtained based on the study cohort, and needs to be prospectively validated in other comparable patient cohorts. Further, mitral annulus was assessed only at end-systole. While previous studies have shown that mitral annulus is smallest at end-systole (26,27), further evaluation throughout the cardiac cycle is needed in the future. Finally, the lack of regular echocardiographic follow-up of the study subjects limited our ability to further explore the relationship between MAD, left atrial reverse remodeling, LV reverse remodeling, and the prognosis of TAVR.

Conclusions

MAD assessment with CT was convenient and reproducible. MAD was common in patients with severe AR undergoing TAVR, and was an independent predictor of all-cause death and heart-failure hospitalization. MAD offered incremental prognostic value for the risk assessment that comprised clinical and echocardiographic parameters.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1608/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-1608/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University (No. B2023-005R), and the requirement of individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Toff WD, Hildick-Smith D, Kovac J, Mullen MJ, Wendler O, et al. Effect of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation vs Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Aortic Stenosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022;327:1875-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Virtanen MPO, Eskola M, Jalava MP, Husso A, Laakso T, Niemelä M, et al. Comparison of Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement vs Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement Among Patients With Aortic Stenosis at Low Operative Risk. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e195742. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC, Moses JW, Tuzcu EM, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:2477-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vahl TP, Thourani VH, Makkar RR, Hamid N, Khalique OK, Daniels D, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with high-risk symptomatic native aortic regurgitation (ALIGN-AR): a prospective, multicentre, single-arm study. Lancet 2024;403:1451-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Kong XQ, Gao XF, Chen J, Chen X, Li B, Shao YB, Wang Y, Jiang H, Zhu JC, Zhang JJ, Chen SL. Transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement with VitaFlow(TM) valve for pure native aortic regurgitation in patients with high surgical risk: Rationale and design of a prospective, multicenter, and randomized SEASON-AR trial. Am Heart J 2024;271:76-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu L, Guo Y, Wang W, Liu H, Yang Y, Wei L, Wang C. Transapical transcatheter aortic valve replacement with a novel transcatheter aortic valve replacement system in high-risk patients with severe aortic valve diseases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:588-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pai RG, Varadarajan P. Prognostic implications of mitral regurgitation in patients with severe aortic regurgitation. Circulation 2010;122:S43-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang LT, Enriquez-Sarano M, Scott CG, Padang R, Maalouf JF, Pellikka PA, Michelena HI. Concomitant Mitral Regurgitation in Patients With Chronic Aortic Regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:233-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delgado V, Tops LF, Schuijf JD, de Roos A, Brugada J, Schalij MJ, Thomas JD, Bax JJ. Assessment of mitral valve anatomy and geometry with multislice computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:556-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reid A, Ben Zekry S, Naoum C, Takagi H, Thompson C, Godoy M, Anastasius M, Tarazi S, Turaga M, Boone R, Webb J, Leipsic J, Blanke P. Geometric differences of the mitral valve apparatus in atrial and ventricular functional mitral regurgitation. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2022;16:431-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grewal J, Suri R, Mankad S, Tanaka A, Mahoney DW, Schaff HV, Miller FA, Enriquez-Sarano M. Mitral annular dynamics in myxomatous valve disease: new insights with real-time 3-dimensional echocardiography. Circulation 2010;121:1423-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelghani M, Abdel-Wahab M, Hemetsberger R, Landt M, Merten C, Toelg R, Richardt G. Fate and long-term prognostic implications of mitral regurgitation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Int J Cardiol 2019;288:39-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferruzzi GJ, Silverio A, Giordano A, Corcione N, Bellino M, Attisano T, Baldi C, Morello A, Biondi-Zoccai G, Citro R, Vecchione C, Galasso G. Prognostic Impact of Mitral Regurgitation Before and After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Severe Low-Flow, Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis. J Am Heart Assoc 2023;12:e029553. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mavromatis K, Thourani VH, Stebbins A, Vemulapalli S, Devireddy C, Guyton RA, Matsouaka R, Ghasemzadeh N, Block PC, Leshnower BG, Stewart JP, Rumsfeld JS, Lerakis S, Babaliaros V. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Aortic Stenosis and Mitral Regurgitation. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:1977-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blanke P, Weir-McCall JR, Achenbach S, Delgado V, Hausleiter J, Jilaihawi H, Marwan M, Norgaard BL, Piazza N, Schoenhagen P, Leipsic JA. Computed tomography imaging in the context of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) / transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR): An expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2019;13:1-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weir-McCall JR, Blanke P, Naoum C, Delgado V, Bax JJ, Leipsic J. Mitral Valve Imaging with CT: Relationship with Transcatheter Mitral Valve Interventions. Radiology 2018;288:638-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blanke P, Dvir D, Cheung A, Ye J, Levine RA, Precious B, Berger A, Stub D, Hague C, Murphy D, Thompson C, Munt B, Moss R, Boone R, Wood D, Pache G, Webb J, Leipsic J. A simplified D-shaped model of the mitral annulus to facilitate CT-based sizing before transcatheter mitral valve implantation. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2014;8:459-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Hahn RT, Han Y, Hung J, Lang RM, Little SH, Shah DJ, Shernan S, Thavendiranathan P, Thomas JD, Weissman NJ. Recommendations for Noninvasive Evaluation of Native Valvular Regurgitation: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:303-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1-39.e14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barbanti M, Webb JG, Hahn RT, Feldman T, Boone RH, Smith CR, Kodali S, Zajarias A, Thompson CR, Green P, Babaliaros V, Makkar RR, Szeto WY, Douglas PS, McAndrew T, Hueter I, Miller DC, Leon MB. Impact of preoperative moderate/severe mitral regurgitation on 2-year outcome after transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement: insight from the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve (PARTNER) Trial Cohort A. Circulation 2013;128:2776-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Onofrio A, Gasparetto V, Napodano M, Bianco R, Tarantini G, Renier V, Isabella G, Gerosa G. Impact of preoperative mitral valve regurgitation on outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:1271-6; discussion 1276-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marsit O, Clavel MA, Côté-Laroche C, Hadjadj S, Bouchard MA, Handschumacher MD, Clisson M, Drolet MC, Boulanger MC, Kim DH, Guerrero JL, Bartko PE, Couet J, Arsenault M, Mathieu P, Pibarot P, Aïkawa E, Bischoff J, Levine RA, Beaudoin J. Attenuated Mitral Leaflet Enlargement Contributes to Functional Mitral Regurgitation After Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:395-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Debonnaire P, Al Amri I, Leong DP, Joyce E, Katsanos S, Kamperidis V, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ, Marsan NA, Delgado V. Leaflet remodelling in functional mitral valve regurgitation: characteristics, determinants, and relation to regurgitation severity. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:290-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casaclang-Verzosa G, Gersh BJ, Tsang TS. Structural and functional remodeling of the left atrium: clinical and therapeutic implications for atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cortés C, Amat-Santos IJ, Nombela-Franco L, Muñoz-Garcia AJ, Gutiérrez-Ibanes E, De La Torre Hernandez JM, et al. Mitral Regurgitation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Prognosis, Imaging Predictors, and Potential Management. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:1603-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alkadhi H, Desbiolles L, Stolzmann P, Leschka S, Scheffel H, Plass A, Schertler T, Trindade PT, Genoni M, Cattin P, Marincek B, Frauenfelder T. Mitral annular shape, size, and motion in normals and in patients with cardiomyopathy: evaluation with computed tomography. Invest Radiol 2009;44:218-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banks T, Razeghi O, Ntalas I, Aziz W, Behar JM, Preston R, Campbell B, Redwood S, Prendergast B, Niederer S, Rajani R. Automated quantification of mitral valve geometry on multi-slice computed tomography in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy - Implications for transcatheter mitral valve replacement. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018;12:329-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]