Pancreatic and extra-pancreatic transabdominal ultrasound findings of type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis

Introduction

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a rare type of chronic pancreatitis with clinical, serological, radiological, and histological characteristics that suggest an autoimmune mechanism (1). The International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC) identify the following two types of AIP: type 1 AIP, also known as lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, which is an important manifestation of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related diseases (1); and type 2 AIP, also known as idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis (2). Clinically, the most typical indications and symptoms of AIP are jaundice, weight loss, abdominal pain, and hyperglycemia.

Serological evidence supporting the diagnosis of type 1 AIP includes raised immunoglobulin G (IgG)/IgG4 levels or identified autoantibodies. Radiologically, AIP is characterized by diffuse or focal pancreatic swelling, and the narrowing of the pancreatic duct and/or common bile duct. Pathologically, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis may be found. Morphologically, when AIP affects the entire pancreas, it should be distinguished from common chronic pancreatitis, as the former can be treated with steroids to restore normal morphology and pancreatic function (3). When AIP is found in a portion of the pancreas, it must be differentiated from cancer, which is generally characterized by an increased level of carbohydrate-associated antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and cannot be treated with steroids.

In recent years, transabdominal ultrasound (TUS) features have rarely been described in the majority of published imaging studies, which have focused on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (1,4-7). Further, when ultrasound was examined in relation to other types of radiographs, few remarks were provided. Thus, this study sought to retrospectively analyze pancreatic and extra-pancreatic ultrasonography findings in patients with AIP, and to determine the value of TUS in the diagnosis of AIP. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-110/rc).

Methods

Patients

Due to the difficulties in diagnosing AIP, many criteria have been developed, including the Mayo Clinic criteria (8,9), Korean criteria (10), Japanese criteria (JPS2018) (11,12), Italian criteria (13), Asian criteria (14), and the ICDC (15). The ICDC was applied in this study.

In total, 23 patients with a diagnosis of type 1 AIP were identified in The First Hospital of China Medical University database between 2003 and 2021; ultrasound images were available for 19 of these patients, of whom 12 were men (mean age: 52.75±14.72 years; median age: 52 years; range: 33–83 years) and seven were women (mean age: 52.71±17.68 years; median age: 54 years; range: 18–71 years). The patients had an overall age range of 18–83 years, a mean age of 52.84±15.33 years, and a median age of 54 years. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of China Medical University (No. AF-SOP-07-1.0-01), and informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Machines and images

All ultrasound images were retrospectively obtained from the computer system. The examination equipment comprised Philips IU22, Siemens Acuson Seqoia 512, Toshiba aplio80, Aloka α10, and SuperSonic Imagine AixPlorer. The pancreas, peripancreatic lymph nodes, gall bladder, bile ducts, retroperitoneal region, and kidneys were all examined with convex probes with frequencies ranging from 3.5 to 5 MHz. The parotid glands, submandibular glands, and lacrimal glands were all evaluated using linear probes with frequencies ranging from 7.5 to 14 MHz. All the examinations were performed by qualified technicians or doctors with at least seven years of experience each.

B-mode sonograms of the pancreas, peripancreatic lymph nodes, gall bladder, bile ducts, retroperitoneal space, and kidneys were available for all 19 patients. Color Doppler flow images (CDFIs) of the pancreas were available for eight patients, but the CDFIs did not detect the peripancreatic lymph nodes, gall bladder, or bile ducts. B-mode sonographies of parotid glands, submandibular glands, and lacrimal glands were available for 10 patients, and CDFIs were obtained for one, three, and five of patients respectively. Pancreatic contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and TUS-guided pancreatic biopsy using an 18G automated puncture needle results were available for one patient.

Follow up and therapy

Seven patients were followed up, of whom, five were treated with steroids.

Image analysis

All the sonographies were analyzed by at least two experienced sonographers. The following aspects were examined: size, morphology, and echoes of the pancreas, kidneys, parotid glands, submandibular glands, and lacrimal glands; peripancreatic lymphadenopathy; gallbladder size and thickness; inner diameters of bile ducts; and retroperitoneal fibrosis. CDFIs were also examined if they were available (Table 1).

Table 1

| Ultrasound manifestations | Diffuse type (n=9) | Segmental type (n=5) | Focal type (n=5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Texture homogeneous/heterogeneous | 6/3 | 3/2 | 4/1 |

| Capsule-like echo | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Dilated main pancreatic duct | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Calcification | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Peripancreatic lymph nodes | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| CDFI (vascular/available) | 1/2 | 3/5 | 0/1 |

| Dilated intrahepatic biliary duct | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Contrast‑enhanced ultrasound | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dilated common bile duct | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Enlarged gallbladder | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Thickened wall | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Kidney | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Retroperitoneal fibrosis | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Parotid gland involved/available | 0/6 | 3/5 | 0/1 |

| CDFI (vascular/available) | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 |

| Submandibular gland involved/available | 2/6 | 3/5 | 0/1 |

| CDFI (vascular/available) | 1/1 | 1/2 | 0/0 |

| Lacrimal gland involved/available | 4/6 | 4/5 | 0/1 |

| CDFI (vascular/available) | 2/2 | 3/3 | 0/0 |

Data are expressed as the number. CDFI, color Doppler flow image.

CT, MR, MRCP, ERCP, serologic, and histopathologic evaluations

CT, MR, MRCP, and ERCP images were available for 17, 10, 8, and 5 of the 19 patients, respectively. Serum IgG and antinuclear antibody levels were determined for 16 patients. Other laboratory data, such as serum amylase, blood glucose, and the tumor marker CA19-9, were available for 13, 13, and 17 patients, respectively. Histopathology results were available for five patients.

Results

Clinical features

The clinical symptoms of the patients mainly included jaundice (n=11, 57.89%), upper abdomen pain (n=12, 63.16%), and weight loss (n=11, 57.89%). Serum IgG levels were increased in nine of 16 (56.25%) patients. Four out of 16 patients (25%) were positive for antinuclear antibodies. Serum amylase levels were increased in 3 of 13 (23.08%) patients. Blood glucose levels were increased in 8 of 13 (61.54%) patients. CA19-9 levels were increased in 8 of 17 (47.06%) patients.

TUS findings

Pancreas and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy

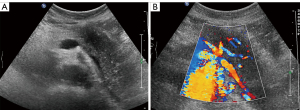

According to the distribution of the lesions, the pancreatic images were classified into three types: diffuse, segmental, and focal. Nine of the 19 (47.37%) patients had the diffuse type of API, resulting in diffuse enlargement of the whole pancreas. The pancreatic parenchyma was hypoechoic (Figure 1), with either homogeneous (n=6) or heterogeneous (n=3) echoes. The pancreatic capsule-like echo was thick and coarse in 4 (44.44%) patients. The main pancreatic duct was dilated in 3 (33.33%) patients, with diameters ranging from 3.3–8.6 mm (mean: 5.3 mm). A calcification-like hyperechoic lesion was found in 1 (11.11%) patient, but it was not certified by CT. Peripancreatic lymph nodes were detected in 2 (22.22%) patients, with maximum diameters of 13.2 and 25 mm, respectively. CDFI was used to assess two of the nine patients, and one showed relative vascularity. CEUS revealed hypo-enhancement in one patient throughout the whole pancreas (Figure 2).

Five of the 19 (26.32%) patients had the segmental type of AIP, which manifested as the segmental enlargement of the pancreas with homogeneous (n=3) or heterogeneous (n=2) hypoechoic parenchyma. The enlargement was located in the body and tail of the pancreas. The capsule-like echo around the lesion was thick and coarse in four (80%) patients. The main pancreatic duct was dilated in 2 (40%) patients, with diameters of 4.0 and 5.0 mm, respectively. None of the five patients exhibited calcification. Peripancreatic nodes were found in 1 (20%) patient (Figure 3), and the maximum diameter of the nodes was 16.7 mm. Of the five patients, four were examined by CDFI, and two of these patients showed vascularity (Figure 4).

Five of the 19 (26.32%) patients had the focal type of AIP, which manifested as the focal enlargement of the pancreas with homogeneous (n=4) or heterogeneous (n=1) hypoechoic parenchyma, mimicking a pancreatic tumor. The lesions were located at the head and/or uncinate process of the pancreas. The capsule-like echo around the lesion was thick and coarse in 4 (80%) patients. The main pancreatic ducts were dilated in 3 (60%) patients, and measured 3.5, 8.0, and 4.0 mm, respectively. No calcification was found in any of the five patients. A peripancreatic node was found in 1 (20%) patient, with a maximal diameter of 14 mm. Of the five patients, one was examined by CDFI, and vascularity was not observed.

Bile ducts and gall bladder

Dilated intrahepatic biliary and common bile ducts were observed in 11 (57.89%) patients (Figure 5). The dilated common bile duct measured 11–21 mm (mean: 15.1±2.6 mm) in diameter. Six (31.58%) patients had an enlarged gall bladder with sludge, and 7 (36.84%) patients had a thickened gallbladder wall (Figure 6), ranging in thickness from 3.8 to 6.6 mm (mean: 5.2±1.1 mm).

Kidneys

Sixteen patients (32 kidneys) were observed by ultrasonography. Except for one patient with hydronephrosis caused by retroperitoneal fibrosis, neither B-mode ultrasonography nor the CDFIs revealed any abnormalities.

Retroperitoneal involvement

Retroperitoneal fibrosis was found in 1 patient (5.26%), which was characterized by a soft tissue mass enclosing the abdominal aorta, involved the left ureter, and was associated with hydronephrosis (Figure 7).

Parotid, submandibular, and lacrimal glands

Of the 19 patients, the parotid, submandibular, and lacrimal glands of 10 were observed by ultrasonography, which revealed diffuse enlargement of the glands with heterogeneous echo texture and multiple round hypoechoic areas similar to Sjögren’s syndrome. Of the 10 patients, parenchymal inhomogeneity was detected in the bilateral parotid glands of 3 (30%) patients, bilateral submandibular glands of 5 (50%) patients, and bilateral lacrimal glands of 8 (80%) patients. CDFIs revealed increased blood flow perfusion in one pair of parotid glands of one patient, two pairs of submandibular glands of three patients (Figure 8), and five pairs of lacrimal glands of five patients (Figure 9).

Follow-up imaging

Follow-up imaging examinations were performed for seven patients. Of these patients, five had been treated with steroids. After therapy, two diffuse types of AIP changed to focal type or segmental type, respectively. The enlarged pancreas shrank after therapy in two diffuse type patients and one segmental type patient. Two patients who showed segmental enlargement of the pancreas at initial ultrasonography refused to receive treatment, and follow-up ultrasonography revealed enlargement of the whole pancreas.

Discussion

AIP is a special type of chronic pancreatitis. AIP was first described by Yoshida in 1995 (16). In recent years, extensive research has been conducted into the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. The clinical symptoms of AIP are non-specific and primarily include jaundice, upper abdominal pain, and weight loss. Our study included 12 men and 7 women. Elderly patients are particularly vulnerable to AIP, and AIP is more common in males and the elderly (17).

As reported previously (17), most patients with AIP have increased IgG (IgG4) and/or antinuclear antibody levels. This was also observed in our study, where 56.25% of the patients had increased IgG levels, and 25% had increased antinuclear antibody levels. Similar findings have been reported in other studies (18-20). In addition, the serum CA19-9 levels were increased in 47.06% of the patients in this study, which is higher than that reported in another study (20).

The diagnosis of AIP is based on imaging, serology, histopathology, other organ involvement, and response to steroids (11). In recent years, many studies have focused on CT and MR. The appearance of AIP is often described as diffuse enlargement of the entire pancreas, and is sometimes described as “sausage-like” or focal enlargement of the pancreas, mimicking carcinoma. Calcifications and pseudocysts are uncommon in AIP (21). Although the above studies sometimes had involved ultrasound, content was not expounded systematically. Neither pancreatic sonographies, nor extra-pancreatic sonographies were described in detail. In most articles, AIP was described as diffuse enlargement of the entire pancreas or focal mass (22,23); however, segmental types were rarely mentioned.

In the present study, 5 patients (26.32%) showed segmental enlargement of the body and tail of the pancreas. This type of AIP is so distinct that it can readily be distinguished from other pancreatic diseases. Thus, we regard segmental enlargement of the body and tail of the pancreas as an important feature in the diagnosis of AIP. We also observed a well-defined capsule-like echo surrounding the pancreas in 63.16% of the patients. Research has reported that rim-enhancement is hypointense on T2 MR, indicating the presence of peripheral inflammation and fibrosis (1,6). Thus, the rim is a crucial point in the differentiation of AIP from other pancreatic diseases.

In the patient follow up, we found that the three types of AIP can transform into each other. Therefore, while it cannot be said that there are three types of AIP in terms of pathology, there are three types of manifestations of AIP in terms of ultrasonography. Further, the manifestations can change from one type to another, with or without therapy. Different types of AIP merely indicate the different locations of the main lesion.

Jaundice is often the first symptom of AIP. Ultrasonography is typically performed first to determine the cause of jaundice (24). Jaundice occurs due to an obstruction of the bile ducts. In our study, biliary involvement was observed in 57.89% of the patients, which was lower than the 75% reported in the literature (25). Both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts may be involved in AIP. Pancreatic duct involvement was observed in 42.11% of the patients. On ERCP or MRCP, the affected bile and pancreatic duct often manifest as stenosis (26). On CT, biliary involvement may manifest as the thickening and enhancement of the bile duct wall (27). However, these abnormalities are difficult to detect on ultrasonography due to the gastrointestinal gas and/or lower resolution of low-frequency ultrasound. The stenotic pancreatic and biliary ducts can only be detected indirectly through distal duct dilation. Gallbladder involvement was detected in 36.84% of the patients, and it manifested as diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall and/or enlargement of the gallbladder.

In one report, abdominal lymphadenopathy was observed in more than half of the patients who underwent laparotomy for AIP (28). However, peripancreatic lymph nodes were found only in 21.05% of the patients. Thus, most of the lymph nodes were not detected due to the low resolution of the ultrasound.

Renal involvement is present in about 35% of patients with AIP (29). It can be categorized into the following four patterns on CT and MR: round lesions; well-circumscribed wedge-shaped lesions; small peripheral cortical nodules; and diffuse patchy involvement. On ultrasonography, none of the upper manifestations were found, either in the B-mode ultrasounds or CDFIs. This may be related to the deficiency of the contrast, as lesions are only visible during the enhancement phase. Thus, CEUS may be helpful in diagnosis of AIP, and additional studies should be conducted to confirm whether CEUS could be used.

Many other autoimmune diseases have been linked to AIP, including retroperitoneal fibrosis and Sjögren’s syndrome (30). Retroperitoneal fibrosis was observed in only 1 patient (5.26%) in our study, which is lower than the previously reported 10% (6). Salivary gland involvement was reported in 15% of patients in the literature (31). Conversely, in our study, it was observed in 30–80% of the patients The images mimic those of Sjögren’s syndrome, which can be easily detected by ultrasound. Notably, lacrimal gland changes occurred in 80% of the patients. This may be a key point in differentiating AIP from tumors and other types of chronic pancreatitis.

Conclusions

AIP is a disorder that involves multiple systems. Ultrasonography is valuable in the diagnosis of AIP, particularly the segmental type of AIP. The capsule-like echo may be specific to the diagnosis of the disease. The biliary duct system, salivary glands, and lacrimal glands are the most typically involved organs outside the pancreas that can be detected by ultrasonography. The biliary duct system is non-specific. The salivary and lacrimal glands are more common and particular. Nevertheless, CEUS and TUS-guided pancreatic biopsy may play a crucial role in differentiating AIP from malignancies.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-110/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-110/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of China Medical University (No. AF-SOP-07-1.0-01), and informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ishikawa T, Kawashima H, Ohno E, Mizutani Y, Fujishiro M. Imaging diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis using endoscopic ultrasonography. J Med Ultrason (2001) 2021;48:543-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palazzo L. Second-generation fine-needle biopsy for autoimmune pancreatitis: ready for prime time? Endoscopy 2020;52:986-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Castañón M, de las Heras-Castaño G, López-Hoyos M. Autoimmune pancreatitis: an underdiagnosed autoimmune disease with clinical, imaging and serological features. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:237-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irie H, Honda H, Baba S, Kuroiwa T, Yoshimitsu K, Tajima T, Jimi M, Sumii T, Masuda K. Autoimmune pancreatitis: CT and MR characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;170:1323-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morana G, Tapparelli M, Faccioli N, D'Onofrio M, Pozzi Mucelli R. Autoimmune pancreatitis: instrumental diagnosis. JOP 2005;6:102-7.

- Sahani DV, Kalva SP, Farrell J, Maher MM, Saini S, Mueller PR, Lauwers GY, Fernandez CD, Warshaw AL, Simeone JF. Autoimmune pancreatitis: imaging features. Radiology 2004;233:345-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zandieh I, Byrne MF. Autoimmune pancreatitis: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:6327-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Zhang L, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Vege SS, Farnell MB. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1010-6; quiz 934. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chari ST. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis using its five cardinal features: introducing the Mayo Clinic's HISORt criteria. J Gastroenterol 2007;42:39-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim KP, Kim MH, Kim JC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune chronic pancreatitis revisited. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:2487-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Notohara K, Fujinaga Y, Inoue D, Koyama T, Okazaki K. Japanese Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Pancreatitis, 2018: Revision of Japanese Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Pancreatitis, 2011. Pancreas 2020;49:e13-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimosegawa TWorking Group Members of the Japan Pancreas Society. Research Committee for Intractable Pancreatic Disease by the Ministry of Labor, Health and Welfare of Japan. The amendment of the Clinical Diagnostic Criteria in Japan (JPS2011) in response to the proposal of the International Consensus of Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC) for autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2012;41:1341-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frulloni L, Gabbrielli A, Pezzilli R, Zerbi A, Cavestro GM, Marotta F, Falconi M, Gaia E, Uomo G, Maringhini A, Mutignani M, Maisonneuve P, Di Carlo V, Cavallini G. PanCroInfAISP Study Group. Chronic pancreatitis: report from a multicenter Italian survey (PanCroInfAISP) on 893 patients. Dig Liver Dis 2009;41:311-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Otsuki M, Chung JB, Okazaki K, Kim MH, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Park SW, Shimosegawa T, Lee K, Ito T, Nishimori I, Notohara K, Naruse S, Ko SB, Kihara Y. Asian diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: consensus of the Japan-Korea Symposium on Autoimmune Pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2008;43:403-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Mino-Kenudson M, Kim MH, Klöppel G, Lerch MM, Löhr M, Notohara K, Okazaki K, Schneider A, Zhang LInternational Association of Pancreatology. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas 2011;40:352-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida K, Toki F, Takeuchi T, Watanabe S, Shiratori K, Hayashi N. Chronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune abnormality. Proposal of the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:1561-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Majumder S, Takahashi N, Chari ST. Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:1762-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi H, Ishiwatari H, Imai K, Kishida Y, Ito S, Hotta K, Yabuuchi Y, Yoshida M, Kakushima N, Takizawa K, Kawata N, Ono H. Steroid Therapy and Steroid Response in Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Int J Mol Sci 2019;21:257. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blaho M, Dítě P, Kunovský L, Kianička B. Autoimmune pancreatitis - An ongoing challenge. Adv Med Sci 2020;65:403-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa T, Kawashima H, Ohno E, Iida T, Suzuki H, Uetsuki K, Yamada K, Yashika J, Yoshikawa M, Gibo N, Aoki T, Kataoka K, Mori H, Fujishiro M. Risks and characteristics of pancreatic cancer and pancreatic relapse in autoimmune pancreatitis patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;35:2281-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dite P, Novotny I, Trna J, Sevcikova A. Autoimmune pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2008;22:131-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ogawa H, Takehara Y, Naganawa S. Imaging diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Med Ultrason (2001) 2021;48:565-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandrasegaran K, Menias CO. Imaging in Autoimmune Pancreatitis and Immunoglobulin G4-Related Disease of the Abdomen. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2018;47:603-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ren D, Lv M, Ye D, Jin D, Ouyang Y. Bedside ultrasound in tigecycline-associated acute pancreatitis: a case description. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023;13:8793-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Madhani K, Farrell JJ. Autoimmune Pancreatitis: An Update on Diagnosis and Management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2016;45:29-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugumar A, Levy MJ, Kamisawa T, Webster GJ, Kim MH, Enders F, et al. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography criteria to diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis: an international multicentre study. Gut 2011;60:666-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takahashi N, Fletcher JG, Fidler JL, Hough DM, Kawashima A, Chari ST. Dual-phase CT of autoimmune pancreatitis: a multireader study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;190:280-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A. Extrapancreatic lesions in autoimmune pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005;39:904-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takahashi N, Kawashima A, Fletcher JG, Chari ST. Renal involvement in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: CT and MR imaging findings. Radiology 2007;242:791-801. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz G, Stone JH. Clinical Perspectives on IgG4-Related Disease and Its Classification. Annu Rev Med 2022;73:545-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Sakaki N, Inokuma S, Kamata N. Salivary gland involvement in chronic pancreatitis of various etiologies. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:323-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]