Development and validation of a prediction model of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency, accounting for 90–95% of all diabetes cases (1). It is associated with both macrovascular and microvascular diseases and often coexists with poor lifestyle factors, obesity, hypertension, and fatty liver, which increase the risk of diabetes-related organ damage, such as peripheral vascular disease, retinopathy, renal dysfunction, and coronary artery disease (CAD). T2DM was thought to be an important contributor in accelerating the progression of heart failure (HF), even independent of CAD or hypertension (2,3). Numerous studies suggest that left ventricular longitudinal myocardial systolic dysfunction (LVSD) is a crucial factor in diabetes-related cardiovascular events (4-7), and is regarded as a preclinical marker of DM-related cardiac dysfunction without overt HF (7,8).

The specific causes leading to impaired systolic longitudinal strain during LV are still unclear, so early assessment and identification of risk factors involved in the progression of LVSD are eagerly awaited. Although studies, such as Mochizuki et al.’s (5) research on 144 samples, have attempted to identify predictors of LVSD in T2DM patients, they have been limited by sample size and confounding factors. Moreover, no nomogram-based predictive models have been developed. Hence, we aimed to develop and validate a model for early prediction of risk factors for LVSD in T2DM patients using routinely measured variables. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-95/rc).

Methods

Study population

Initially, 345 patients with T2DM who were admitted to The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University between June 2020 to October 2021 were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) diagnosed with T2DM (American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria in 2020) (9), (II) age between 18 and 75 years, (III) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) >50%. We excluded those with LVEF <50% (n=5), poorly controlled hypertension (n=8), CAD (n=7), atrial fibrillation (n=5), and poor image quality (n=10). Finally, 310 patients were enrolled for the present study. Subsequently, participants were randomly assigned to the training and validation sets according to a ratio of 7:3. A flow chart outlining the selection of T2DM patients is shown in Figure 1. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (No. 20240805102436398) and informed consent was provided by all the patients.

Data collection

Information was collected on baseline clinical data (age, sex, duration of diabetes, history of medication,), physical measurements [height, weight, body mass index (BMI), systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP), heart rate (HR)], laboratory examination [glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density/low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C/LDL-C), urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR)], and diabetic microvascular complications, including diabetic retinopathy (DR), diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), and diabetic nephropathy (DN). Occurrence of DPN was evaluated by experienced diabetologists according to nerve conduction study and current guidelines (9). Moreover, DR was diagnosed by experienced ophthalmologists, either on fundoscopy or retinography (10). DN was defined as albuminuria of not less than 30 mg/day accompanied by GFR >30 mL/min/1.73 m2) (11).

Echocardiography

All patients underwent standard two-dimensional (2D) transthoracic echocardiographic examination with commercial Vivid E95 ultrasound scanners equipped with a M5SC-D transducer (GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway). 2D gray-scale echocardiography of three consecutive cardiac cycles was obtained from standard parasternal and apical views upon calm breathing. Sector width was optimized to maximize frame rate and achieve the whole LV myocardial visualization concurrently. All standard acquisitions and measurements were completed relying on the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography (12).

Measurement of global longitudinal myocardial strain

To perform the speckle tracking strain analysis, three standard apical views (apical four-chamber, two-chamber, and three-chamber) were acquired using grayscale harmonic imaging at frame rates between 50–80 frames/s and was saved in cine-loop digital format for offline analysis. Quantification of 2D strain was performed with dedicated software (EchoPAC 203, GE). The algorithm automatically traces the endocardial border or width throughout the cardiac cycle and calculates strain values at the three apical views; if necessary, end-diastolic frame was manually contoured for optimal assessment. GLS was then determined as the average value of the peak systolic longitudinal strain of each myocardial segment from the three apical views. For this study, we chose to report global longitudinal strain (GLS) using the absolute value. As previously detailed, LVSD in T2DM patients with preserved LVEF was set at GLS <18% (5,8,13).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (for normally distributed data) or median [interquartile range (IQR)] (for non-normally distributed data), and independent t-test or the Wilcoxon test was used for comparisons between groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency/percentage (%) and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. To address potential collinearity and avoid overfitting, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis was used to screen risk factors and optimal predictive features from a large set of variables in T2DM patients. Subsequently, multivariable logistic regression analysis is performed. Finally, the risk factors were visualized with a forest plot and a nomogram was constructed based on these factors. Model performance was evaluated through discrimination ability [with area under the curve (AUC) >0.7 indicating satisfactory performance], calibration (using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and calibration curve), and clinical utility [assessed by decision curve analysis (DCA)]. The P values were two-sided and considered significant if <0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), R software (version 4.1.1; http://www.r-project.org/), and the R package with ‘rio’, ‘rms’, ‘glmnet’, ‘InformationValue’, ‘forestplot’, ‘ROCR’, ‘rmda’, ‘ResourceSelection’, and ‘regplot’.

Results

Characteristics of patients with T2DM This study included 310 T2DM patients with an average age of 56 years; 217 comprised the training set and 93 comprised the validation set. Of the 310 patients included, 130 patients (41.9%) presented with LVSD, with 86 (39.6%) in the training set and 44 (47.3%) in the validation set, respectively. All baseline characteristics of both sets are summarized in Table 1. The variables did not show statistical differences except for eGFR and E/e’, which were comparable in both the training and validation sets (P>0.05).

Table 1

| Clinical characteristics | Training set (n=217) | Validation set (n=93) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.9±11.6 | 57.7±9.6 | 0.156 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 80 (36.9) | 33 (35.5) | 0.817 |

| Male | 137 (63.1) | 60 (64.5) | |

| T2DM duration (years) | 6 (1–10) | 7 (2–10) | 0.346 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.72±0.18 | 1.72±0.18 | 0.966 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.4±3.4 | 24.4±2.9 | 0.078 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130.6±17.4 | 132.2±17.3 | 0.461 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81.1±10.2 | 80.9±9.0 | 0.848 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 76.9±12.0 | 76.8±10.9 | 0.950 |

| Laboratory results | |||

| HbA1c (%) | 8.6 (6.8–10.2) | 7.9 (6.5–10.0) | 0.321 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2±1.5 | 5.0±1.4 | 0.208 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.53 (1.07–2.55) | 1.63 (1.12–2.66) | 0.569 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.14 (2.49–3.85) | 2.86 (2.26–3.80) | 0.503 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.12 (0.92–1.37) | 1.07 (0.87–1.35) | 0.359 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 5.73±1.88 | 5.76±1.63 | 0.886 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 105.4 (82.0–126.4) | 87.9 (75.6–105.3) | <0.001 |

| Albumin to creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 12 (4.00–52.55) | 15.6 (6.26–67.4) | 0.321 |

| Diabetic microvascular complications | |||

| Retinopathy | 156 (71.9) | 72 (77.4) | 0.312 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 49 (22.6) | 29 (31.2) | 0.110 |

| Nephropathy | 66 (30.4) | 32 (34.4) | 0.488 |

| Medications | |||

| Metformin | 161 (74.2) | 60 (64.5) | 0.084 |

| Sulfonylureas | 72 (33.2) | 32 (34.4) | 0.834 |

| Glitazones | 46 (21.2) | 18 (19.4) | 0.713 |

| Insulin | 86 (39.6) | 31 (33.3) | 0.295 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs | 119 (54.8) | 43 (46.2) | 0.165 |

| Statins | 126 (58.1) | 55 (59.1) | 0.860 |

| Echocardiography | |||

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 89.3±18.7 | 90.3±24.0 | 0.704 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 65.9±4.1 | 65.2±4.3 | 0.151 |

| E/e’ | 11.5±3.1 | 13.2±3.3 | <0.001 |

| GLS (%) | 18.0±2.0 | 17.9±2.2 | 0.930 |

| GLS <18% (%) | 86 (39.6) | 44 (47.3) | 0.209 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data and median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data, or n (%). T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACE, angiotensin-convertingenzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; LV, left ventricular; E, peak early diastolic mitral flow velocity; e’, spectral pulsed-wave Doppler-derived early diastolic; GLS, global longitudinal strain.

Feature selection

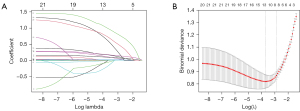

LASSO method was used for the selection of potential predictors from the training set, which allowed for reducing the dimensionality that was associated with decreased predictive ability and improving the accuracy of the nomogram model. Seven variables in the LASSO regression analysis were selected as potential predictors based on the results of 217 patients with nonzero coefficients (min λ of 0.056), which included BMI, T2DM duration, BUN, left ventricular mass index (LVMI), E/e’, DR, DN, and DPN, (Figure 2A,2B).

Independent risk factors and nomogram construction

Multivariate logistic analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors in the training set based on the most significant features selected by LASSO. The results (Table 2) revealed that BMI [odds ratio (OR): 1.248; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.082–1.439; P=0.002]; DM course (OR: 1.149; 95% CI: 1.047–1.261; P=0.003); BUN (OR: 1.312; 95% CI: 1.030–1.671; P=0.028); LVMI (OR: 1.034; 95% CI: 1.008–1.060; P=0.009); E/e’ (OR: 1.267; 95% CI: 1.065–1.507; P=0.007); DR (OR: 3.264; 95% CI: 1.091–9.764; P=0.034); DPN (OR: 2.999; 95% CI: 1.047–8.589; P=0.041); and DN (OR: 3.878; 95% CI: 1.455–10.337; P=0.007) were independent risk factors of LVSD, as shown in the forest plot (Figure 3A). Underlying the above introduced results, a nomogram was constructed by integrating these independent risk factors (Figure 3B). In the nomogram, each predictor corresponds to a specific score by drawing its straight line at the top of the scale and drawing a vertical line from the total points axis down to the LVSD risk axis. Finally, the predicted probability of LVSD was obtained.

Table 2

| Variable | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.248 (1.082–1.439) | 0.002 |

| T2DM duration (years) | 1.149 (1.047–1.261) | 0.003 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 1.312 (1.030–1.671) | 0.028 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 1.034 (1.008–1.060) | 0.009 |

| E/e’ | 1.267 (1.065–1.507) | 0.007 |

| Retinopathy | 3.264 (1.091–9.764) | 0.034 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 2.999 (1.047–8.589) | 0.041 |

| Nephropathy | 3.878 (1.455–10.337) | 0.007 |

LVSD, left ventricular longitudinal myocardial systolic dysfunction; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LV, left ventricular; E, peak early diastolic mitral flow velocity; e’, spectral pulsed-wave Doppler-derived early diastolic.

Performance assessment of the nomogram

The results showed that the AUC was 0.922 (95% CI: 0.886–0.958) and 0.918 (95% CI: 0.859–0.978) for the training and validation sets, respectively, indicating excellent discrimination (Figure 4A,4B). The calibration was also good in the training and validation sets (Figure 4C,4D), with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test showing no significant difference (P>0.05). DCA indicated that the nomogram had higher net benefit compared to assuming all patients have LVSD, within a risk threshold range of 40% to 95% (Figure 5).

Clinical application of the nomogram

We randomly selected a patient as an example of practicing the nomogram: BMI (29.6 kg/m2), T2DM duration (5.0 years), BUN level (5.5 mmol/L), LVMI (73.3 g/m2), E/e’ (11.5) and the presence of DR and DN. By applying the above values to the nomogram, the probability of DR was estimated to be 66.2% (Figure 6).

Discussion

Currently, nomograms are widely used as prognostic tools in medicine and oncology (14). A nomogram-based predictive model is capable of improving accuracy, and provides more easily understood prognoses to help make better clinical decisions (15). Our study is the first nomogram to predict the risk factors of LVSD in T2DM patients. The major findings indicate that the incidence of LVSD is 41.9%. Patients with LVSD have higher BMI, longer duration of T2DM, elevated BUN, increased LVMI, and E/e’, and are more likely to have complications such as DR, DPN, and DN. BMI, T2DM course, BUN, LVMI, E/e’, DR, DPN, and DN are independent risk factors for LVSD, with DN being the highest risk factor. Our predictive model demonstrates acceptable accuracy and discrimination. Based on the eight risk factors listed in the nomogram, it is easy to calculate the score and estimate the probability of developing LVSD in T2DM patients.

In this work, we developed a quantifiable and simple nomogram to predict the risk factors for LVSD for T2DM patients. The specific implementation steps were as follows: all patients were randomly divided into groups at a 7:3 ratio for training and validation, respectively. LASSO regression was used to select features, then perform multivariable logistic regression analysis. Finally, the risk factors were visualized with a forest plot and a nomogram was constructed based on these factors. After validation by multiple methods, our nomogram showed excellent performance with respect to discrimination ability, calibration ability, and clinical usefulness.

In our study, overweight/obesity (indicated by a high BMI) was found to be an independent risk factor for LVSD, consistent with previous research (16-18). Obesity-related inflammation, metabolic disturbances, and insulin resistance may worsen LV function (19). LVSD was also associated with the duration of diabetes. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and their receptors (RAGEs) negatively impact the heart and promote atherosclerosis (20). Long-term hyperglycemia and poorly controlled diabetes can alter hemoglobin structure, increasing erythrocyte viscosity and contributing to microangiopathy and diabetic complications (21). Among ultrasonic features, LVMI and E/e’ were identified as independent risk factors for LVSD. E/e’ is closely related to LV filling pressures (22), and long-term dysglycemia may directly or indirectly contribute to elevated filling pressures and increased risk of HF symptoms and mortality (23). Larger LVMI indicates more severe cardiac hypertrophy, which can lead to apoptosis, autophagy, and extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis abnormalities, potentially altering gene expression related to LVSD over time (24). Furthermore, our results align with those of Pararajasingam et al. (25) and Mochizuki et al. (5), showing that microvascular complications (including DR, DPN, and DN) are associated with impaired GLS in T2DM patients, independent of CAD. Microvascular complications in diabetes often arise early and are interlinked through complex pathological mechanisms. Evidence suggests that patients with one or more complications are more susceptible to microvascular dysfunction, such as reduced myocardial perfusion (26,27). We hypothesize that the deterioration of cardiac function in patients with microvascular complications may be due to severe pathological abnormalities in the myocardium, including neurohormonal and metabolic disturbances (e.g., apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis), as well as microvascular and cardiac remodeling abnormalities (28-30).

Limitations

Despite our efforts to enhance the study’s validity by making the data from the training and validation sets completely independent, several unavoidable limitations remain. First, this study was conducted at a single center with a small sample size. Although model validation was carried out in a validation cohort, external validation was lacking; future multicenter prospective studies are needed to further validate the model and improve individualized risk assessment. Second, the study focused on specific clinical data and echocardiographic parameters, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other factors. Finally, as a cross-sectional study without long-term follow-up, the relationship between LVSD and prognosis in T2DM patients requires further investigation.

Conclusions

This study developed a nomogram-based predictive model with good accuracy and clinical applicability for predicting the risk of LVSD among people with T2DM. This has the potential to be a convenient and accurate tool to predict LVSD in T2DM patients with preserved LVEF.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-95/rc

Funding: This study was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-95/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (No. 20240805102436398) and informed consent was provided by all the patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gloyn AL, Drucker DJ. Precision medicine in the management of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:891-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rydén L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, Berne C, Cosentino F, et al. ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2013;34:3035-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tanaka H, Tatsumi K, Matsuzoe H, Matsumoto K, Hirata KI. Impact of diabetes mellitus on left ventricular longitudinal function of patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020;19:84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki Y, Tanaka H, Matsumoto K, Sano H, Toki H, Shimoura H, Ooka J, Sawa T, Motoji Y, Ryo K, Hirota Y, Ogawa W, Hirata K. Association of peripheral nerve conduction in diabetic neuropathy with subclinical left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015;14:47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki Y, Tanaka H, Matsumoto K, Sano H, Toki H, Shimoura H, Ooka J, Sawa T, Motoji Y, Ryo K, Hirota Y, Ogawa W, Hirata K. Clinical features of subclinical left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015;14:37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki Y, Tanaka H, Matsumoto K, Sano H, Shimoura H, Ooka J, Sawa T, Ryo-Koriyama K, Hirota Y, Ogawa W, Hirata K. Impaired Mechanics of Left Ventriculo-Atrial Coupling in Patients With Diabetic Nephropathy. Circ J 2016;80:1957-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ernande L, Bergerot C, Rietzschel ER, De Buyzere ML, Thibault H, Pignonblanc PG, Croisille P, Ovize M, Groisne L, Moulin P, Gillebert TC, Derumeaux G. Diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: is it really the first marker of diabetic cardiomyopathy? J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:1268-1275.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi Y, Tanaka H, Yokota S, Mochizuki Y, Yoshigai Y, Shiraki H, Yamashita K, Tanaka Y, Shono A, Suzuki M, Sumimoto K, Matsumoto K, Hirota Y, Ogawa W, Hirata KI. Effect of heart rate on left ventricular longitudinal myocardial function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021;20:87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye S, Boulton AJ, Dyck PJ, Freeman R, Horowitz M, Kempler P, Lauria G, Malik RA, Spallone V, Vinik A, Bernardi L, Valensi PToronto Diabetic Neuropathy Expert Group. Diabetic neuropathies: update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2285-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheung N, Mitchell P, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet 2010;376:124-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ramírez HR, Cortés-Sanabria L, Rojas-Campos E, Barragán G, Alfaro G, Hernández M, Canales-Muñoz JL, Cueto-Manzano AM. How frequently the clinical practice recommendations for nephropathy are achieved in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a primary health-care setting? Rev Invest Clin 2008;60:217-26.

- Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF 3rd, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf FA, Gillebert TC, Klein AL, Lancellotti P, Marino P, Oh JK, Popescu BA, Waggoner AD. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:277-314. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ernande L, Bergerot C, Girerd N, Thibault H, Davidsen ES, Gautier Pignon-Blanc P, Amaz C, Croisille P, De Buyzere ML, Rietzschel ER, Gillebert TC, Moulin P, Altman M, Derumeaux G. Longitudinal myocardial strain alteration is associated with left ventricular remodeling in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014;27:479-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ, DeMatteo RP. Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:e173-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei L, Champman S, Li X, Li X, Li S, Chen R, Bo N, Chater A, Horne R. Beliefs about medicines and non-adherence in patients with stroke, diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017293. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blomstrand P, Sjöblom P, Nilsson M, Wijkman M, Engvall M, Länne T, Nyström FH, Östgren CJ, Engvall J. Overweight and obesity impair left ventricular systolic function as measured by left ventricular ejection fraction and global longitudinal strain. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018;17:113. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng ACT, Prevedello F, Dolci G, Roos CJ, Djaberi R, Bertini M, Ewe SH, Allman C, Leung DY, Marsan NA, Delgado V, Bax JJ. Impact of Diabetes and Increasing Body Mass Index Category on Left Ventricular Systolic and Diastolic Function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2018;31:916-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sonaglioni A, Barlocci E, Adda G, Esposito V, Ferrulli A, Nicolosi GL, Bianchi S, Lombardo M, Luzi L. The impact of short-term hyperglycemia and obesity on biventricular and biatrial myocardial function assessed by speckle tracking echocardiography in a population of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2022;32:456-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatani Y, Tanaka H, Mochizuki Y, Suto M, Yokota S, Mukai J, Takada H, Soga F, Hatazawa K, Matsuzoe H, Matsumoto K, Hirota Y, Ogawa W, Hirata KI. Association of body fat mass with left ventricular longitudinal myocardial systolic function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cardiol 2020;75:189-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Pino A, Mangiafico S, Urbano F, Scicali R, Scandura S, D’Agate V, Piro S, Tamburino C, Purrello F, Rabuazzo AM. HbA1c Identifies Subjects With Prediabetes and Subclinical Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:3756-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ye S, Ruan P, Yong J, Shen H, Liao Z, Dong X. The impact of the HbA1c level of type 2 diabetics on the structure of haemoglobin. Sci Rep 2016;6:33352. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan FH, Zhao D, Ha JW, Nagueh SF, Voigt JU, Klein AL, et al. Evaluation of left ventricular filling pressure by echocardiography in patients with atrial fibrillation. Echo Res Pract 2024;11:14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolsk E, Jürgens M, Schou M, Ersbøll M, Hasbak P, Kjaer A, Zerahn B, Høgh Brandt N, Haulund Gæde P, Rossing P, Faber J, Kistorp CM, Gustafsson F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and left heart filling pressures in patients with type 2 diabetes. ESC Heart Fail 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref]

- Liu F, Wang X, Liu D, Zhang C. Frequency and risk factors of impaired left ventricular global longitudinal strain in patients with end-stage renal disease: a two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiographic study. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021;11:2397-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pararajasingam G, Heinsen LJ, Larsson J, Andersen TR, Løgstrup BB, Auscher S, Hangaard J, Møgelvang R, Egstrup K. Diabetic microvascular complications are associated with reduced global longitudinal strain independent of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease in asymptomatic patients with diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2021;21:269. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li XM, Shi R, Shen MT, Yan WF, Jiang L, Min CY, Liu XJ, Guo YK, Yang ZG. Subclinical left ventricular deformation and microvascular dysfunction in T2DM patients with and without peripheral neuropathy: assessed by 3.0 T cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023;22:256. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Potier L, Chequer R, Roussel R, Mohammedi K, Sismail S, Hartemann A, Amouyal C, Marre M, Le Guludec D, Hyafil F. Relationship between cardiac microvascular dysfunction measured with 82Rubidium-PET and albuminuria in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018;17:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marwick TH, Ritchie R, Shaw JE, Kaye D. Implications of Underlying Mechanisms for the Recognition and Management of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:339-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feldman EL, Callaghan BC, Pop-Busui R, Zochodne DW, Wright DE, Bennett DL, Bril V, Russell JW, Viswanathan V. Diabetic neuropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5:41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang QM, Fang JX, Chen XY, Lv H, Kang CS. The Systolic and Diastolic Cardiac Function of Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Evaluation of Left Ventricular Strain and Torsion Using Conventional and Speckle Tracking Echocardiography. Front Physiol 2021;12:726719. [Crossref] [PubMed]