Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) vs. computed tomography (CT) in the diagnosis and classification of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis—a narrative review

Introduction

Spondylolysis is the presence of a unilateral or bilateral defect in the pars interarticularis of the vertebra. The term is derived from the Greek words spondylos (vertebra) and lysis (defect). The pars interarticularis is the junction (isthmus) between the pedicles, articular facets, and lamina. It represents the weakest area of the posterior vertebral arch, especially in children and adolescents, because this arch is not completely ossified and there is greater elasticity of the intervertebral disc, making the pars interarticularis the area most susceptible to fatigue fracture (1).

Spondylolisthesis, on the other hand, refers to the slippage (usually anterior) of one vertebral body over the vertebral body immediately below it, regardless of the cause.

Up to 40% of children and adolescents suffer from low back pain, the prevalence of which increases with age and is similar in adolescents and adults. There are significant differences in the identification of the cause of low back pain (LBP), which depend directly on access to the health system, varying from 78% to 12% in different countries (2,3). Some authors have classified low back pain in athletes into 5 different categories according to the cause: spondylolysis and other changes of the posterior vertebral arch, disc pathology, apophyseal fractures, mechanical pain, and other causes (including tumors, infections, psychosomatic pain, peritoneal irritation) (4).

This article pretends to serve as a review of the typical findings of spondylolysis a spondylolisthesis covering their appearance on all available imaging techniques, focusing on new and more specific magnetic resonance (MR) sequences. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-574/rc).

Methods

The literature available in English from 1976 (when the first publications on the diagnosis of this pathology appeared) up to the present day has been used for this review (Table 1).

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | December 2023 |

| Databases searched | PubMed |

| Search terms used | Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, radiograph, CT, MRI, low back pain |

| Timeframe | From 1976 to December 2023 |

| Inclusion criteria | Only papers in Spanish or English |

| Selection process | Selection conducted by the authors |

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Narrative

Etiology and pathogenesis

The exact etiology of spondylolysis remains unknown, although it is likely that pars elongation has a multifactorial origin due to predisposing and environmental factors (5,6).

The preference for the lumbosacral junction is related to the fact that the sacrum is relatively immobile, while the lumbar spine is the segment with the greatest flexibility. The anterior elements (vertebral body and intervertebral disc) resist compressive forces, while the posterior vertebral elements resist shear forces. The pars is the junction between these elements and is the area of greatest mechanical stress as it must withstand compressive and shear forces. During repetitive rotation and flexion-extension movements of the spine, compression of the pars L5 occurs between the inferior articular process of L4 and the superior articular process of S1, leading to the development of microfractures and, in the case of prolonged stress, to the development of a complete or incomplete fracture. In addition to this biomechanical explanation, there is also an anatomical explanation of spondylolysis, which consists in the demonstration of a relationship between the occurrence of spondylolysis and the interfacial distance in the L3–S1 segment through studies such as that of Ward et al., in which a shorter distance was observed in patients with spondylolysis compared to healthy patients (7-9).

In spondylolysis, 3 stages of the disease have been described (Figure 1):

- Pars stress reaction: bone edema or chronic sclerotic changes are observed, with no clear partial or total fracture line.

- Established spondylolysis: there is a bone defect, total or partial, without associated slippage of the vertebra.

- Spondylolisthesis: produced in cases of bilateral spondylolysis, which favors slippage of the vertebra over the one immediately below.

Both treatment and prognosis depend on the stage at which the disease is diagnosed, being especially important its diagnosis in the earliest (stress) stage, since at this stage conservative treatment with limitation of sporting activity is usually necessary to avoid progression to established lysis and subsequent spondylolisthesis (10).

Spondylolisthesis is defined as an anterior slippage of a vertebra in reference to the vertebra immediately below. Wiltse et al. classified spondylolisthesis into 5 different categories (5). Type 1 or dysplastic, a congenital morphological alteration is observed in the morphology of the superior plateau of S1, which acquires a rounded aspect and thus favors an anterior displacement of the body of L5. Type 2 or isthmic, which is further divided into two subtypes; type 2A, caused by a stress fracture of the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis) and type 2B in which repeated microtrauma with subsequent healing occurs, resulting in an elongation of the pars, without interruption of the pars, and a secondary anterior slippage of the vertebral body. Type 3 or degenerative, secondary to degenerative changes in interfacet joints which may cause a rupture of the yellow ligament, with secondary instability of the spine and displacement of the vertebral body. Type 4 or traumatic, caused by a high energy trauma with the spine in hyperextension. Type 5 or pathological, in cases of lytic tumor lesion that destroys the pars, in osteopetrosis and osteoporosis.

Meyerding et al. defined a system for grading spondylolisthesis using lateral plain radiography, although it can be used on sagittal plane CT and MR images. The system consists of dividing the vertebral plate into four equal parts, and grading spondylolisthesis according to the percentage of displaced vertebra. Grade 1, when there is a slippage of less than 25%. Grade 2, when this percentage is between 26–50%. Grade 3, when the displacement is between 51–75%. Grade 4, when there is a percentage of slippage between 76–100%. Grade 5 refers to a displacement of more than 100%, and is known as spondyloptosis (11-15).

Epidemiology

Spondylolysis and isthmic spondylolisthesis are commonly implicated as organic causes of low back pain in adolescents and may go unrecognized until symptoms develop into adulthood. The real incidence is difficult to known because in many cases it is an asymptomatic pathology that may go unnoticed.

The rates of spondylosis and spondylolisthesis vary widely by age group. The incidence of lumbar spondylolysis in the general population is 3–10%. In the pediatric population, spondylolysis is present in about 5% of the population, most commonly (90%) at the L5 to S1 motion segment, although pathology at L4 is more likely to be symptomatic.

In a radiographic study using computed tomography (CT) in 532 patients aged eight or younger presenting with general lumbar complaints, spondylolysis was diagnosed in 4.7% of the children. With the widespread use of MRI, the incidence has increased to 58% in adolescent and young adult patients presenting with low back pain for more than 2 weeks (11).

A large ethnic variability has been observed, with a higher to lower frequency in Eskimos (40%), Caucasians (5–12%), and African Americans (1–3%). No significant difference in prevalence has been observed between men and women, although there is a greater progression to spondylolisthesis in women (14).

There is a strong association between the presence of a pars defect and the presence of spina bifida occulta (failure of fusion of the vertebral bodies due to abnormal fusion of the posterior vertebral arches, with unexposed neural tissue and skin overlying intact), which occurs in only 5% of the general population but in up to one-third of patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis. The more common and least severe forms consist of isolated vertebral bony defects (Figure 2) (13,14)

Clinical manifestations

Most cases are asymptomatic (87%) and spondylolysis is an incidental finding on imaging studies performed for another cause. However, spondylosis and spondylolisthesis are the most common causes of low back pain in children and adolescents, with the onset of pain attributed to these causes in up to 50% of cases (15).

In symptomatic patients, there may be a large discrepancy between radiologic and clinical findings. When clinical symptoms appear, the most common symptom is low back pain of a mechanical nature, aggravated by sports activity or prolonged standing and improving at rest (16,17).

The appearance of radicular symptoms is less frequent in young patients but may occur in cases of severe vertebral slippage. Two types of radicular pain are distinguished: an atypical radicular pain that is position dependent and not associated with motor symptoms, and a less common one in which sensory and motor symptoms are combined in the setting of sciatica. In these cases, the radicular compression at the level of the root path through the lateral recesses or inside the neural foramina is caused by the presence of hypertrophic fibrous or osseous tissues that lead to a deformity with foraminal stenosis.

Physical examination of patients reveals hyperlordotic posture with pain on hyperextension of the trunk. The reproduction of pain when the patient stands upright on one foot and tilts the trunk backward is considered a practically pathognomonic clinical sign. In cases of unilateral involvement, pain is reproduced when the ipsilateral leg is supported (18).

To compensate for the lumbosacral kyphosis produced by listesis, the patient retroverts the pelvis by verticalizing the sacrum and flexing the knees to shift the center of gravity posteriorly. Pelvic retroversion results in hip extension, which can lead to hamstring contracture (1).

Diagnostic imaging

Role of imaging

When an imaging test is performed in the context of low back pain, other pathologies such as transitional alterations and congenital anomalies (vertebral fusions, total or partial vertebral body defects) should be ruled out, for which plain radiography and CT are especially useful (Figure 3). Neoplastic lesions and degenerative changes, although they can be visualized in the initial plain radiographs, usually require MRI for better diagnosis and characterization.

In patients with localized pain, clinical deformity and alarm symptoms (night pain, weight loss or neurological symptoms) an imaging study should be performed. In addition, they are indicated in case of duration of symptoms longer than 4 weeks in case of children and adolescents, or more than 6 weeks in adults (18).

Plain radiography

Plain radiographs are the first and most important step in the evaluation of any patient with low back pain.

Anteroposterior and lateral projections should be obtained, and in some cases the 45° oblique projection and the collimated lateral projection should be obtained as additional projections.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are useful in the initial evaluation of low back pain, while oblique projections or dynamic studies (flexion and extension of the spine in lateral projection) provide information on vertebral stability (19). Although oblique radiographs have classically been considered more sensitive than PA and lateral projections, recent studies suggest that their inclusion increases radiation and cost, without significantly affecting sensitivity and specificity (20).

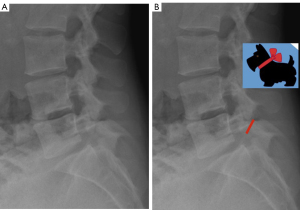

Spondylolysis is observed as a radiolucency at the level of the pars interarticularis (Figure 3A), the width of which varies according to the time of development of the spondylolysis. When the lesion is acute, this radiolucency is narrower and its borders are irregular, whereas in the case of a chronic lesion, the radiolucency is wider and has smooth and well-defined contours. If the bone defect is large, it can be visualized in virtually all projections used, whereas in cases where it is small or there is no significant associated listhesis, other imaging studies may be required.

The “Scotty dog” sign, with the defect occurring at the level of the dog’s neck (pars interarticularis), is visualized only in the oblique projection, but this fracture is detected only when it has a perpendicular trace to the pars (Figure 4) (21). Saifuddin et al. (22) performed a study to evaluate the orientation of fractures on CT and found that most of them occur in a plane close to the coronal plane, which would explain why most of them are detected in the oblique lateral projection (up to 50%) compared to 20% of those visualized in the oblique projection.

In addition to direct visualization of the lysis, indirect radiographic signs that may be helpful in the diagnosis include lateral deviation of the spinous process, bulging of the contour of the affected pars, and sclerosis of the contralateral pedicle. Spinous process deviation translates relative rotation between two vertebrae caused by lamina elongation due to repeated microfractures with healing of the ipsilateral pars. The deviation is assessed in the anteroposterior projection and is defined according to the direction in which the inferior edge of spinous process is oriented; this deviation occurs in the opposite direction to the lysis and is more frequent in cases of unilateral involvement (23). Contour bulging is defined as a widening of the margins along the affected pars. Sclerosis of the contralateral pedicle presents as a callus-like appearance with bony masses in the contour of the contralateral neural arch and is also more prominent in cases of unilateral spondylolysis. In relation to this finding, the radiologic sign of “pedicular anisocoria” has been described (24,25). It represents the physiological response of the bone to stress due to the increased load on the contralateral pedicle and lamina in cases of unilateral spondylolysis (Figure 5).

CT

Despite the higher radiation of CT compared to radiography, CT is considered the best imaging modality for the diagnosis of spondylolysis in the presence of pars interarticularis fracture. The technological advances of recent years in CT equipment allow faster acquisition of studies as well as the availability of three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions that allow better visualization of the bony elements of the lumbar spine. In this sense, the incorporation of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) equipment in radiological services (previously focused on dental studies and therefore available in dental clinics) and allows the performance of studies focused on the affected segment of the spine, with a better definition of the trabeculae and bone cortex, with radiation doses lower than in conventional CT.

CT provides better visualization of bone morphology and facilitates differential diagnosis with other entities. The use of 3D reconstructions allows better detection of the fracture line, as well as assessment of its extension and orientation. It is also able to show several morphologic features of spondylolysis, some of which have implications for consolidation and healing capacity that are difficult to assess with other imaging modalities and are therefore essential in making decisions regarding the clinical management and treatment of this entity.

Classification by evolution

CT/CBCT is able to determine whether the lysis is acute or chronic based on the appearance of the fracture, similar to fractures in the rest of the skeleton, such that the presence of a focal bone defect or radiolucent line with discrete irregular margins but without sclerosis of the margins suggests lysis in the acute phase, whereas a larger bone defect with fragmentation and presence of sclerosis at the margins suggests established lysis in the chronic phase. Because of this differentiation, CT plays an important role in long and short-term therapeutic decisions. A fracture with a wide bone defect and marginal sclerosis will not benefit from conservative treatment with immobilization due to its poor healing capacity, whereas a fracture with a narrow bone defect and without bone sclerosis, suggesting an acute phase, may benefit from early immobilization to allow healing and consolidation (26).

On the other hand, the presence of focal sclerosis in the pars area without a fracture line and without cortical irregularity indicates the presence of a stress reaction secondary to repeated microfractures, but without lysis or established fracture.

Classification by extent and orientation of fracture

CT or CBCT allows visualization of the extent of fracture in cases of established lysis, differentiating between complete fracture or lysis when it extends from the superior cortex to the inferior cortex, and incomplete fracture or lysis in cases where only one of the pars cortices is involved, showing an interruption of the inferomedial cortex of the pars with the superior cortex intact, indicating that the direction of fracture in cases of spondylolysis is from inferior to superior (27). The differentiation between complete and incomplete lysis is best observed in sagittal plane reconstructions (Figure 3B).

On the other hand, CBCT is able to visualize the fracture line regardless of its orientation, unlike plain radiology and MRI. The determination of such orientation is important because differences in fracture angulation with respect to the long axis of the pars have implications for the decision of surgical technique in cases where repair is indicated (28).

In some times, fragmentation of the lamina is observed in association with spondylolysis. Such involvement of the lamina is not observed in the absence of spondylolysis, its visualization in plain radiology or CT studies helps in the detection of spondylolysis (29).

Evaluation of other findings associated with lysis

In cases of unilateral spondylolysis, CT/CBCT is able to detect with greater sensitivity and specificity the presence of sclerosis and compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral pars, as well as deviation of the spinous process.

Even in the absence of associated spondylolisthesis, patients with bilateral spondylolysis may have an increase in the anteroposterior diameter of the central canal due to elongation of the pars interarticularis (30). This finding allows in many cases to differentiate isthmic spondylolysis from degenerative spondylolysis, since in the latter, there is an overall decrease in the caliber of the central canal due to vertebral slippage, the presence of marginal osteophytosis dependent on vertebral platelets, degeneration of the intervertebral disc, as well as the presence of degenerative changes in the posterior vertebral elements, generally of hypertrophic aspect, which also contributes to a stenosis of the neural foramen.

In cases of isthmic spondylolysis, the involvement of the conjunctival foramina consists of a morphologic change with loss of alignment between the superior and inferior halves, best assessed in the sagittal plane, although in most cases the caliber is preserved. However, in the presence of degenerative disc disease or significant disc pseudobulging associated with listhesis, there is a decrease in the height of the intersomatic space, which may contribute to decrease the anteroposterior diameter of the vertebral canal.

In other cases, the foraminal stenosis is caused by an occupation of the foramen by the reparative fibrous tissue that occurs in the area of the lysis. This hypertrophic tissue is often the cause of compressive symptoms of the nerve roots, even when the bony displacement is small and there is no significant stenosis of the bony framework of the foramina and is therefore difficult to evaluate in CT or CBCT studies due to the poor resolution of these in the evaluation of soft tissues. The density of the nerve roots is similar to that of the intervertebral disc and reparative fibrous tissue, so the relationship between these structures can only be assessed in cases where there is sufficient adipose tissue surrounding the nerve roots.

Another cause of decreased foraminal caliber is the presence of bony projections or small osteophytes associated with the formation of fibrous or cartilaginous tissue during the lysis repair process. In some cases, this repair process is very exuberant and may result in a significant reduction in foraminal caliber. Visualization of these bone spurs or proliferations is only possible on CT or CBCT scans. This reparative tissue usually proliferates medially and creates an impression on the lateral margin of the dural sac. If the growth occurs anteriorly, it may result in obliteration of the lateral recess with involvement of the nerve roots at that level (Figure 6).

In general, the evaluation of radicular pathology associated with spondylolysis requires the performance of an MRI study.

Over the years, studies have been performed evaluating CT scans performed on groups of adults with other causes (urological, abdominal, vascular pathology), observing a prevalence of spondylolysis in approximately 11% of cases, most of them without significant association with the presence of low back pain (31). For this reason, it is important to recognize the radiological signs of lysis on axial CT images, especially when the examination is not focused on the lumbar spine and when 3D reconstructions are not available to facilitate the evaluation of the pars interarticularis.

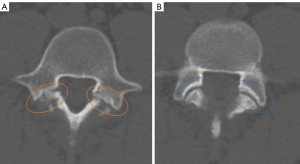

In axial images, the neural arch is continuous and completely closed at the level of the pedicles. The presence of a bony discontinuity at this level indicates the presence of a pars defect (incomplete ring sign). However, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish a lysis from the adjacent interfacial joint when images are evaluated only in the axial plane, since both have a similar orientation and are separated by a few millimeters.

In general, the lysis has a slightly more horizontal orientation and the bony margins are usually more irregular, with associated sclerosis and the absence of a groove or indentation for the joint capsular insertion, whereas the interfacial joints have a more oblique arrangement in the axial plane, with smooth bony margins without associated sclerosis and with a small indentation at the margins corresponding to the capsular insertion zone (Figure 7).

Recently, some radiologic features have been described that may help in its detection, such as the “Darth Vader sign” (32). While the appearance of the typical Darth Vader helmet resembles the anterior and anterolateral contour of the lumbar vertebral bodies, the cervical area represents the irregular interruption visualized in cases of lysis. In contrast, the bony not traduction (GAP) representing the facet joint is easily distinguished due to its orientation and lack of irregularity.

MR

Although CT is considered the “gold standard” technique for visualizing the bony anatomy of the neural arch because of its ability to demonstrate the presence of complete or incomplete lysis, MRI has shown greater sensitivity for detecting early changes secondary to stress or overload at the level of the pars. It is currently widely used as the initial imaging technique in the evaluation of young patients with low back pain and radiculopathy. It also plays a fundamental role in the diagnosis of other pathologies that may be the cause of similar low back pain symptoms, such as the presence of degenerative disc disease, facet joint pathology, fractures of vertebral plates or transverse processes, or anomalies of the lumbosacral transition, among others.

The basic MRI study protocol for the diagnosis of spondylolysis should include at least sagittal and axial (3 mm) T1-weighted images and fluid-sensitive sequences [T2 or short TI inversion recovery (STIR)]. It is useful to add other sequences that allow a better visualization of the fracture such as ultrashort time-to-echo sequences and VIBE T2, because of its usefulness at acquiring signal from cortical bone, or 3D sequences that allows a correct visualization of the fracture line, providing information on its extent and orientation (32,33).

Pars lysis appears as disruption of the cortical and medullary bone and can be seen on both T1- and T2-weighted sagittal sequences as areas of signal attenuation due to the presence of sclerosis in the fracture zone. T1-weighted sequences will best demonstrate the pars interarticularis defect due to the high contrast between the hyperintense marrow and the markedly hypointense cortex (Figure 8).

MRI classification of pars interarticularis changes

There are numerous studies describing the findings of spondylolysis on MRI and allowing its classification. Hollenberg et al. (34) proposed a classification for the diagnosis and grading of lumbar spondylolysis based on the visualization in the sagittal plane of the pars interarticularis, the pedicle and the adjacent articular facet, evaluating signal changes in the fluid-sensitive sequences (T2 or STIR) as well as morphological changes in the T1-weighted sequence.

Based on the findings, the pars interarticularis changes are classified into 5 evolutionary grades. Grade 0 (normal), no signal changes in the bone marrow at the level of the pars interarticularis. Grade 1 (stress reaction), T2 signal changes with or without signal changes in the adjacent pedicle and articular process. This is stress edema in the absence of a fracture line. Grade 2 (incomplete fracture), presence of signal changes on T2-weighted sequence with thinning, fragmentation, or irregularity of the pars interarticularis visible on T1 and T2-weighted sequences. Grade 3 (established fracture), presence of unilateral or bilateral cortical disruption with associated T2 signal changes. Grade 4 (chronic fracture), complete spondylolysis is seen without signal changes in T2 weighted sequences. These are considered old ununited fractures of the pars (Figure 9).

This classification system is based on the combination of morphologic changes (assessed in T1-weighted sequences) and signal changes (assessed in T2-weighted or STIR sequences) and is able to distinguish between stress response and active or inactive spondylolysis. It has also been shown to have high intra- and interobserver correlation.

The MRI classification of spondylolysis can overlap with the CT classification, both of which provide information on the stage of the disease with a view to the therapeutic approach. In this way, the initial phase in CT (stress/overload phase) which would show no or minimal bone changes by this technique, would be much more evident in MRI studies with the presence of bone oedema in the pars area (stage 1 by MRI). The stage of spondylolysis established on CT (stage 2) correlates with stages 2, 3 and 4 of the MRI classification, where there is already an established partial or complete fracture, with better definition of the fracture on CT studies. In these early stages, conservative treatment would be indicated with the intention of reducing pain and favouring healing of the bone defect. In addition, the determination of the presence of reparative and healing bone changes with fracture healing, or hypertrophic bone changes in relation to non-healing (corresponding to stage 4) are better visualized in CT studies. The presence of such reparative changes is important as spondylolysis that does not show healing phenomena in approximately 6 months or more is considered to require surgical treatment.

Indirect signs of spondylolysis on MRI

MRI diagnosis of spondylolysis in the absence of spondylolisthesis can be difficult because it is sometimes not easy to visualize cortical or complete interruption of the pars in the different pulse sequences used. Therefore, some indirect findings that indicate the presence of lysis are of great importance and usefulness. The three indirect signs that have been shown to be diagnostic of spondylolysis are the increase in the sagittal diameter of the central canal, the wedging of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body at the level of the spondylolysis, and the presence of signal changes in the pedicles adjacent to the pars defect (Figure 10).

The presence of an increase in the anteroposterior diameter of the central canal, measured in the mid-sagittal plane, is a reliable predictor of the presence of pars interarticularis defects; it is also a particularly useful radiologic sign for differentiating between spondylolisthesis of isthmic and degenerative cause, since in the latter case the central canal shows a general decrease in diameter due to the presence of osteophytes, associated degenerative disc disease, and hypertrophic changes in the interfacet joints, including thickening of the yellow bands (Figure 11). An increase in the anteroposterior diameter of the canal is considered when the ratio is equal to or greater than 1.25 with respect to the immediately superior level (35). Ulmer et al. demonstrated the presence of this sign in 100% of patients with grade II, III, and IV spondylolisthesis and in up to 95% of patients with grade I spondylolisthesis (36).

Posterior wedging of the vertebral body is defined as a decrease in the height of the posterior wall of the body with respect to the anterior wall, using as a measure the lumbar index calculated by dividing the height of the posterior wall by the height of the anterior wall, both measurements obtained in the sagittal plane at the level of the midline of the vertebral body. If this division is less than or equal to 0.75, significant posterior wedging is considered. Ulmer et al. demonstrated the presence of this wedging in approximately 25% of patients with spondylolysis without associated listhesis, in approximately 50% of patients with grade I listhesis, in 75% of patients with grade II spondylolisthesis, and in all patients with grade III and IV spondylolisthesis.

The detection of signal changes in the pedicles adjacent to the pars defect is the last of the signs that have demonstrated diagnostic value in cases of spondylolysis when the pars defect is difficult to visualize. Signal changes are classified according to the same classification developed by Modic for vertebral plate signal changes in degenerative disc disease. Type I changes are characterized by decreased signal on T1-weighted sequences with increased signal on T2-weighted sequences, indicating the presence of fibrovascular tissue. Type II changes present a characteristic signal hyperintensity on T1-weighted sequences, with iso- or hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences and translate a fatty conversion of the bone marrow. Type III changes are characterized by low signal on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences associated with bone sclerosis. Pedicle signal changes may occur in the absence of the other two indirect signs described above and are therefore a key finding in the diagnosis of spondylolysis on MRI studies. It can also be of great importance in the early diagnosis of spondylolysis (mainly in the case of type I signal changes) and therefore plays an important role in the early treatment of this pathology, thus preventing progression to pars fracture.

On the other hand, a study by Park et al. described the presence of indirect radiographic signs useful in the diagnosis of unilateral spondylolysis. The appearance of a pseudarthrosis in the pars defect is visualized as a narrow GAP with irregular margins between the edges of the lysis, with or without associated bony signal changes, and with fluid in the bony defect. Sometimes an alteration in the distribution of epidural fat is also described, assessed on axial and sagittal T1-weighted sequences, with interposition of epidural fat between the posterior margin of the thecal sac and the anterior margin of the spinous process, or with asymmetry in the amount of such fat between the affected and contralateral side (Figure 12).

An increase in the interspinous distance is another indirect sign of the presence of unilateral spondylolysis. Normally, this distance decreases progressively in the craniocaudal direction due to physiological lordosis. An increase in this distance is considered when it is greater than the immediate cranial level (37).

The combination of direct signs in MRI with visualization of the pars interarticularis defect in combination with the presence of indirect signs increases the sensitivity of this imaging technique in the diagnosis of spondylolysis, which is close to the sensitivity of CT and radiography.

Assessment of root involvement

Spondylolysis may result in root involvement at the level of both the lateral recesses and the conjunctival foramina, with or without associated spondylolysis. Involvement of the central canal is less common; as described above, the increase in the anteroposterior diameter of the central canal is characteristic of spondylolysis and isthmic spondylolisthesis, as opposed to degenerative etiology.

MRI allows evaluation of several factors that influence nerve root involvement.

On the one hand, the presence of scar tissue in the area of the pars defect may be very prominent and cause a decrease in the caliber of the lateral recess in the anteroposterior diameter, with possible root involvement at this level. This involvement is correctly assessed on T1- and T2-weighted sequences in the sagittal and axial images (38).

The presence of true disc herniation associated with spondylolysis is rare. A posterior bulging of the disc caused by a rupture of the upper portion of the annulus fibrosus due to the sliding of the inferior plateau of the slipped vertebra over this annulus can be seen with some frequency. This bulging contributes to the reduction of the lateral recess and conjunctival foramen. A posterior diffuse pseudo posterior disc bulge is more common due to vertebral slippage, which contributes to the reduction of the caliber of the lateral recess and the neural foramen.

As for the foraminal involvement, in addition to the two causes previously described, it mainly consists of a morphological alteration secondary to the presence of spondylolisthesis, with a virtual division of the same in the longitudinal axis and a loss of alignment between the upper and lower halves, due to the anteroinferior sliding of the upper half of the foramen, which is better visualized in the images obtained in the sagittal plane. The presence of partial or complete obliteration of the perineural fat at the level of the foramen is indicative of root involvement at this level and is easily detected on sagittal T1-weighted sequences (39).

Treatment

Most spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents is mild and has a low risk of progression, although it is important to diagnose and treat (if necessary) as early as possible.

The treatment of spondylolisthesis and spondylolisthesis is initially conservative and is based on the restriction of athletic activities that involve the transmission of extension and torsional forces through the pars, together with the use of a lumbosacral antilordotic orthosis for 3–6 months, which allows unloading of the posterior vertebral elements, thus reducing the amount of force transmitted through the pars (39). In addition to these two mainstays of conservative treatment, a post-bracing program of trunk and pelvic stabilization exercises is recommended to reduce lumbar lordosis and improve flexibility of the trunk extensor musculature.

Surgical treatment is reserved for those patients with persistence of symptoms despite conservative treatment (for more than 6 months). Low back pain is the most common symptom and usually develops during peak growth spurts, so it is likely that this skeletal growth and the changes in physical activity that usually occur at puberty contribute to an increase in symptoms. Depending on the severity of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis, different surgical techniques are used.

In cases of low-grade spondylolisthesis, one can opt for a pars repair aimed at restoring the anatomy and stability of the segment, maintaining its mobility, or for in situ posterolateral fusion, which is the technique of choice for surgical treatment in children and adolescents with L4 or greater spondylolisthesis, when the intersomatic disc is normal.

When there is a high-grade spondylolisthesis, surgical treatment is focused on relieving pain, resolving neurological dysfunction and achieving a solid arthrodesis, minimizing the number of fused segments.

Conclusions

Lumbar spondylolysis is a relatively common process that causes low back pain in young athletes and results from repeated and prolonged stress on the pars interarticularis of the posterior arch of the posterior vertebral elements, which is the weakest area of the posterior arch.

Early diagnosis in the early stages is essential to avoid interruption of the stress response to established lysis through conservative management of cessation of sports activity and postural correction. When lysis is complete and associated with listhesis, surgical treatment may be required.

Plain radiographic diagnosis can be made once the fracture has been established, observing a radiolucency at the level of the pars with a separation between the bony borders that varies according to the time of evolution of the spondylolysis.

CT is considered the gold standard technique for visualization of the fracture, as it allows a more accurate assessment of the extent of the fracture, the angulation of the fracture, and the bony changes associated with the lysis repair process, which can lead to a reduction of the central canal as well as the bony framework of the posterior elements. However, because nerve roots have a similar density to other soft tissues on CT images, this technique is not sensitive enough to assess root involvement secondary to the presence of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

MRI plays a fundamental role in the diagnosis of the earliest stages of spondylolysis, when there is only a stress reaction without an established fracture line or lysis. It also plays a fundamental role in the assessment of nerve structure involvement due to a reduction in the caliber of the lateral recesses and the neural foramen in cases of spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis.

It is important to know the direct and indirect radiological signs in the different imaging techniques to make an accurate diagnosis of spondylolisthesis and its associated alterations.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: With the arrangement by the Guest Editors and the editorial office, this article has been reviewed by external peers.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at: https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-574/rc

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-24-574/coif). The special issue “Advances in Diagnostic Musculoskeletal Imaging and Image-guided Therapy” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mora-de Sambricio A, Garrido-Stratenwerth E. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol 2014;58:395-406. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suzuki H, Kanchiku T, Imajo Y, Yoshida Y, Nishida N, Taguchi T. Diagnosis and Characters of Non-Specific Low Back Pain in Japan: The Yamaguchi Low Back Pain Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160454. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaspiris A, Grivas TB, Zafiropoulou C, Vasiliadis E, Tsadira O. Nonspecific low back pain during childhood: a retrospective epidemiological study of risk factors. J Clin Rheumatol 2010;16:55-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurd DP. Back pain in the young athlete. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2011;19:7-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiltse LL, Newman PH, Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976;23-9.

- Saraste H. Long-term clinical and radiological follow-up of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Pediatr Orthop 1987;7:631-8.

- Chung SB, Lee S, Kim H, Lee SH, Kim ES, Eoh W. Significance of interfacet distance, facet joint orientation, and lumbar lordosis in spondylolysis. Clin Anat 2012;25:391-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ward CV, Latimer B, Alander DH, Parker J, Ronan JA, Holden AD, Sanders C. Radiographic assessment of lumbar facet distance spacing and spondylolysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:E85-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koslosky E, Gendelberg D. Classification in Brief: The Meyerding Classification System of Spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020;478:1125-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Staudenmann A, Marth AA, Stern C, Fröhlich S, Sutter R. Long-term CT follow-up of patients with lumbar spondylolysis reveals low rate of spontaneous bone fusion. Skeletal Radiol 2024;53:2377-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lemoine T, Fournier J, Odent T, Sembély-Taveau C, Merenda P, Sirinelli D, Morel B. The prevalence of lumbar spondylolysis in young children: a retrospective analysis using CT. Eur Spine J 2018;27:1067-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nitta A, Sakai T, Goda Y, Takata Y, Higashino K, Sakamaki T, Sairyo K. Prevalence of Symptomatic Lumbar Spondylolysis in Pediatric Patients. Orthopedics 2016;39:e434-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mataki K, Koda M, Shibao Y, Kumagai H, Nagashima K, Miura K, Noguchi H, Funayama T, Abe T, Yamazaki M. Spina Bifida Occulta with Bilateral Spondylolysis at the Thoracolumbar Junction Presenting Cauda Equina Syndrome. Case Rep Orthop 2020;2020:2425637. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morimoto M, Sugiura K, Higashino K, Manabe H, Tezuka F, Wada K, Yamashita K, Takao S, Sairyo K. Association of spinal anomalies with spondylolysis and spina bifida occulta. Eur Spine J 2022;31:858-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyerding H. Low backache and sciatic pain associated with spondylolisthesis and protruded intervertebral disc: incidence, significance, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1941;23:461-70.

- McNeely ML, Torrance G, Magee DJ. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Man Ther 2003;8:80-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wood KB, Fritzell P, Dettori JR, Hashimoto R, Lund T, Shaffrey C. Effectiveness of spinal fusion versus structured rehabilitation in chronic low back pain patients with and without isthmic spondylolisthesis: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:S110-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah SA, Saller J. Evaluation and Diagnosis of Back Pain in Children and Adolescents. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016;24:37-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spivak JM, Kummer FJ, Chen D, Quirno M, Kamerlink JR. Intervertebral foramen size and volume changes in low grade, low dysplasia isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1829-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Standaert CJ, Herring SA. Spondylolysis: a critical review. Br J Sports Med 2000;34:415-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Micheli LJ, Wood R. Back pain in young athletes. Significant differences from adults in causes and patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:15-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saifuddin A, White J, Tucker S, Taylor BA. Orientation of lumbar pars defects: implications for radiological detection and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998;80:208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park JS, Moon SK, Jin W, Ryu KN. Unilateral lumbar spondylolysis on radiography and MRI: emphasis on morphologic differences according to involved segment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;194:207-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- HADLEY LA. Bony masses projecting into the spinal canal opposite a break in the neural arch of the fifth lumbar vertebra. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1955;37-A:787-97.

- Araki T, Harata S, Nakano K, Satoh T. Reactive sclerosis of the pedicle associated with contralateral spondylolysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17:1424-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiltse LL, Jackson DW. Treatment of spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976;92-100.

- Dunn AJ, Campbell RS, Mayor PE, Rees D. Radiological findings and healing patterns of incomplete stress fractures of the pars interarticularis. Skeletal Radiol 2008;37:443-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amato M, Totty WG, Gilula LA. Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology 1984;153:627-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Hide IG, Papastefanou S, Greenough CG. Juvenile spondylolysis: a comparative analysis of CT, SPECT and MRI. Skeletal Radiol 2005;34:63-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, Guermazi A, Berkin V, Hunter DJ. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: prevalence and association with low back pain in the adult community-based population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:199-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huber FA, Schmidt CS, Alkadhi H. Diagnostic Performance of the Darth Vader Sign for the Diagnosis of Lumbar Spondylolysis in Routinely Acquired Abdominal CT. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023;13:2616. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siriwanarangsun P, Statum S, Biswas R, Bae WC, Chung CB. Ultrashort time to echo magnetic resonance techniques for the musculoskeletal system. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2016;6:731-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campbell RS, Grainger AJ. Optimization of MRI pulse sequences to visualize the normal pars interarticularis. Clin Radiol 1999;54:63-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hollenberg GM, Beattie PF, Meyers SP, Weinberg EP, Adams MJ. Stress reactions of the lumbar pars interarticularis: the development of a new MRI classification system. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:181-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ulmer JL, Elster AD, Mathews VP, King JC. Distinction between degenerative and isthmic spondylolisthesis on sagittal MR images: importance of increased anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal ("wide canal sign"). AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;163:411-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ulmer JL, Mathews VP, Elster AD, Mark LP, Daniels DL, Mueller W. MR imaging of lumbar spondylolysis: the importance of ancillary observations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;169:233-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Major NM, Helms CA, Richardson WJ. MR imaging of fibrocartilaginous masses arising on the margins of spondylolysis defects. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;173:673-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kushchayev SV, Glushko T, Jarraya M, Schuleri KH, Preul MC, Brooks ML, Teytelboym OM. ABCs of the degenerative spine. Insights Imaging 2018;9:253-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steiner ME, Micheli LJ. Treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis with the modified Boston brace. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1985;10:937-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]