Predicting the pathological invasiveness in patients with a solitary pulmonary nodule via Shapley additive explanations interpretation of a tree-based machine learning radiomics model: a multicenter study

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death worldwide (1,2). According to the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lung cancer (3), both atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) were redefined as precursor glandular lesions, with a 5-year survival rate of 100% (4). Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC) are adenocarcinomas of lung, with a 5-year survival rate of 95–100% and 38–86%, respectively (5). Therefore, active follow-up is essential for preglandular lesions; however, timely surgical intervention is recommended for IACs.

Computed tomography (CT) is a common imaging method that plays an important role in the assessment of the invasiveness of pulmonary nodules (6). However, the radiological signs of invasive and noninvasive pulmonary nodules overlap (5,7,8). Radiomics can help assess the benign and malignant invasiveness and prognosis of pulmonary nodules (5,9,10). However, owing to the lack of interpretability and “black box” nature, the specific decision-making mechanism and deduction process of machine learning-based radiomics models are not clear, which might limit the application of the model (11-13).

By virtue of its ability to illustrate how each feature’s value affects the impact of the feature attributed to the model and by visualizing the integration of the features’ impact attributed to individual response, the Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) algorithm is currently the most recommended for model explanation (14-16). The tree-based extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) machine learning model can visualize the deduction process of the prediction model using a tree-based decision diagram, which simulates the clinical diagnostic process of clinicians (15,17,18). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have reported the integration of SHAP and tree-based decision techniques for explaining and visualizing the pathological invasiveness of pulmonary nodules.

This study aimed to construct and validate an interpretable and generalized clinical-radiomics model to precisely distinguish precursor glandular lesions from IACs and thus provide a noninvasive tool for the accurate evaluation of the pathological invasiveness of pulmonary nodules. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-23-615/rc).

Methods

Patients and data collection

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University (The First People’s Hospital of Shunde) (No. KYLS20220701), and the institutional review board waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study. Patients with a solitary pulmonary nodule were recruited from three independent hospitals, including Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University (The First People’s Hospital of Shunde) from February 2020 to May 2022 (Hospital I), Jiaxing TCM Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Chinese Medical University from March 2020 to September 2022 (Hospital II), and Lecong Hospital of Shunde from May 2020 to August 2022 (Hospital III). All participating hospitals/institutions were informed and agreed with the study.

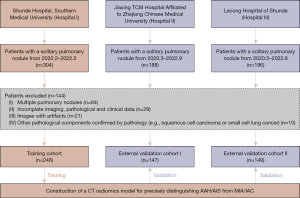

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are illustrated in Figure 1. Ultimately, 248 patients were enrolled from Hospital I and included in the training cohort, and 296 patients were enrolled at Hospitals II (n=147) and III (n=149) and included in the external validation cohorts I and II, respectively. The following were the criteria for inclusion: (I) solitary pulmonary nodules ≤30 mm as confirmed by pathology; (II) complete imaging, pathological, and clinical data; (III) no previous cancer-related treatment for pulmonary nodules; and (IV) no history of other malignant tumors. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) multiple pulmonary nodules; (II) incomplete imaging, pathological, or clinical data; (III) images with artifacts; and (IV) other pathological components confirmed by pathology (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma or small cell lung cancer).

Baseline clinicoradiological factors of pulmonary nodules were recorded, including age, sex, nodular length, density, location, CT value, pleural stretch sign, tumor vessel sign, tumor-lung boundary, crescent sign, air bronchogram sign, and vacuolar sign. All images were reviewed on the Picture Archiving and Communication System in a blinded manner by three radiologists (Zhang R, Hong M, and Liu Z), and potential discrepancies were resolved by consultation.

Pathological invasiveness evaluation of pulmonary nodules

According to the 2021 WHO classification, all pathological histologies were evaluated and diagnosed by two senior pathologists with 15 years of experience in pulmonary pathology. All pulmonary nodules were reclassified as AAH, AIS, MIA, or IAC.

CT image acquisition

CT images were obtained using five CT scanners from three hospitals. For Hospital I, patients were examined using 80-slice (Aquilion Prime, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan), 64-slice (Somatom Definition AS, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany), or 64-slice (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens Healthineers) multidetector CT scanners. For Hospital II, a 16-slice CT scanner (LightSpeed, GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the chest CT. For Hospital III, a 64-slice multidetector CT scanner (Ingenuity Core 128, Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was used. The acquisition parameters of the three hospitals were as follows: tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current, 250–300 mAs; field of view (FOV), 350–400 mm; slice thickness, 1–5 mm; reconstruction image thickness, 0.6–0.8 mm; and pitch, 0.8–1.0.

Image segmentation and feature extraction

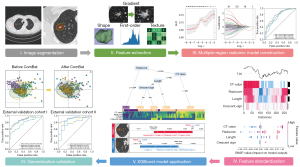

Preoperative CT images were retrieved from the Picture Archiving and Communication System of the three hospitals. The CT images were imported into Deepwise software (https://keyan.deepwise.com/login). Based on the information of each patient, two radiologists with 10 years of experience (Zhang R and Hong M) used a semiautomatic segmentation method to delineate the nodular volume of interest (VOInodule). Another radiologist with 15 years of experience (Liu Z) revised and confirmed the final segmentation results. Based on the average tumoral length (approximately 10 mm), the perinodular diameter was determined to be one-third and half of the length after group discussion; that is, 3 mm VOI (VOI3 mm) and 5 mm VOI (VOI5 mm). Two perinodular regions were then automatically generated using Deepwise software. Large vessels, pleural tissue, surrounding organs, and ribs were manually excluded for each perinodular VOI. A total of 3,045 radiomic features were extracted from three VOIs using the Pyradiomics package in Python and included first-order, shape, gray-level features, square root, and wavelet filtering features. The radiomics analysis process is illustrated in Figure 2. The intragroup correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate the stability of the features. Features with ICC >0.75 were considered sufficiently enough to be retained for subsequent analysis.

Construction of single-region radiomic models

To avoid overfitting and improve the generalization of the model, data up-sampling and a series of coarse-to-fine feature selection strategies were performed. Initially, feature stability was assessed using the ICC method. Subsequently, an independent samples t-test or rank-sum test was performed to select significant features between the AAH/AIS and MIA/IAC groups. Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis was used to reduce the redundancy among the feature sets. When the correlation between feature pairs was greater than 0.6, the feature with a higher average correlation was removed. Additionally, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator logistic regression method was used to choose the optimized subset of radiomic features and construct a single-region radiomics model [nodular radiomics (Radnodule) for VOInodule, 3 mm radiomics (Rad3 mm) for VOI3 mm, and 5 mm radiomics (Rad5 mm) for VOI5 mm].

Construction of a multiple-region radiomics model

To further remove the redundancy of radiomic features from different regions, the variance inflation factor method was applied to quantify the collinearity between radiomic feature pairs. Furthermore, a multiple-region radiomics model was constructed using a logistic model. According to the predictive performance of the four radiomics models, the radiomics score (radscore) was determined by weighting the feature coefficients in the best model.

Construction of clinical-radiomics combined model

Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed on the clinical and radiological factors to screen for pathological invasiveness-related factors (P<0.05). A clinical model was constructed using a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Important clinicoradiological factors and radscore were integrated to construct the clinical-radiomics combined model using logistic regression and the XGBoost algorithm. Shapley additive analysis was used to quantitatively explain the performance of the combined model and visualize the effect of each feature for each patient (19,20).

Generalized validation of models

To verify the generalizability of the predictive models, patients with a solitary pulmonary nodule were retrospectively recruited from Hospitals II and III. With the differences in CT scans and centers being accounted for, CT image preprocessing and the ComBat harmonization technique were conducted to standardize image information and pool the radiomic features together, respectively. Radscore and prediction models were constructed using the same method, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the model performance.

Statistical analysis

Differences in variables between the AAH/AIS and MIA/IAC groups were assessed using the independent samples t-test or rank-sum test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. The SHAP algorithm was run using the “XGBoost” and “SHAP” Python packages. The Combat algorithm was run using the “SVA” R package, and the performance of the model was evaluated using AUC. All statistical analyses were performed using Python (v.3.7.3) and R (v.4.1.3) software. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The baseline clinical and radiological information of patients are shown in Table 1. Imaging data of 544 preoperative patients with a solitary pulmonary nodule were collected from three hospitals. The training cohort included 248 patients from Hospital I. The two external validation cohorts from Hospitals II and III included 147 and 149 patients, respectively. In this study, 25.8% (64/248), 15.0% (22/147), and 7.4% (11/149) of the patients were diagnosed with AAH/AIS in the training cohort and external validation cohorts II and III, respectively.

Table 1

| Items | Hospital I | Hospital II | Hospital III | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAH/AIS (n=64) | MIA/IAC (n=184) | P value | AAH/AIS (n=22) | MIA/IAC (n=125) | P value | AAH/AIS (n=11) | MIA/IAC (n=138) | P value | ||||

| Age (years) | 55.0 (47.0, 60.0) | 56.5 (47.0, 65.3) | 0.310 | 54.5 (47.3, 59.8) | 56.0 (48.0, 65.0) | 0.281 | 57.0 (42.0, 61.5) | 58.5 (49.3, 66.8) | 0.297 | |||

| Sex | 0.723 | 0.347 | 0.543 | |||||||||

| Female | 43 (67.2) | 128 (69.6) | 17 (77.3) | 84 (67.2) | 9 (81.8) | 94 (68.1) | ||||||

| Male | 21 (32.8) | 56 (30.4) | 5 (22.7) | 41 (32.8) | 2 (18.2) | 44 (31.9) | ||||||

| Vacuolar sign | 0.024 | 0.425 | 0.658 | |||||||||

| No | 60 (93.8) | 151 (82.1) | 19 (86.4) | 95 (76.0) | 7 (63.6) | 103 (74.6) | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (6.2) | 33 (17.9) | 3 (13.6) | 30 (24.0) | 4 (36.4) | 35 (25.4) | ||||||

| Air bronchogram | 0.013 | 0.507 | 0.456 | |||||||||

| No | 62 (96.9) | 157 (85.3) | 21 (95.5) | 110 (88.0) | 9 (81.8) | 91 (65.9) | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (3.1) | 27 (14.7) | 1 (4.5) | 15 (12.0) | 2 (18.2) | 47 (34.1) | ||||||

| Crescent sign | <0.001 | 0.122 | >0.999 | |||||||||

| No | 57 (89.1) | 120 (65.2) | 22 (100.0) | 107 (85.6) | 8 (72.7) | 107 (77.5) | ||||||

| Yes | 7 (10.9) | 64 (34.8) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (14.4) | 3 (27.3) | 31 (22.5) | ||||||

| Tumor-lung boundary | 0.299 | 0.998 | 0.908 | |||||||||

| No | 18 (28.1) | 40 (21.7) | 2 (9.1) | 8 (6.4) | 2 (18.2) | 34 (24.6) | ||||||

| Yes | 46 (71.9) | 144 (78.3) | 20 (90.9) | 117 (93.6) | 9 (81.8) | 104 (75.4) | ||||||

| Tumor vessel sign | <0.001 | >0.999 | >0.999 | |||||||||

| No | 18 (28.1) | 17 (9.2) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (4.0) | 7 (63.6) | 82 (59.4) | ||||||

| Yes | 46 (71.9) | 167 (90.8) | 21 (95.5) | 12 (96.0) | 4 (36.4) | 56 (40.6) | ||||||

| Pleural stretch sign | <0.001 | 0.470 | 0.010 | |||||||||

| No | 60 (93.8) | 111 (60.3) | 19 (86.4) | 96 (76.8) | 10 (90.9) | 70 (50.7) | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (6.2) | 73 (39.7) | 3 (13.6) | 29 (23.2) | 1 (9.1) | 68 (49.3) | ||||||

| Component | <0.001 | 0.055 | 0.105 | |||||||||

| SN | 0 (0.0) | 41 (22.3) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (8.0) | 1 (9.1) | 15 (10.9) | ||||||

| mGGN | 14 (21.9) | 76 (41.3) | 6 (27.3) | 57 (45.6) | 2 (18.2) | 67 (48.6) | ||||||

| pGGN | 50 (78.1) | 67 (36.4) | 16 (72.7) | 58 (46.4) | 8 (72.7) | 56 (40.6) | ||||||

| Location | 0.289 | 0.533 | 0.327 | |||||||||

| LLL | 3 (4.7) | 23 (12.5) | 4 (18.2) | 13 (10.4) | 1 (9.1) | 19 (13.8) | ||||||

| LUL | 17 (26.6) | 42 (22.8) | 9 (40.9) | 39 (31.2) | 2 (18.2) | 37 (26.8) | ||||||

| RLL | 12 (18.8) | 41 (22.3) | 2 (9.1) | 19 (15.2) | 1 (9.1) | 27 (19.6) | ||||||

| RML | 3 (4.7) | 13 (7.1) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (4.0) | 3 (27.3) | 12 (8.7) | ||||||

| RUL | 29 (45.3) | 65 (35.3) | 6 (27.3) | 49 (39.2) | 4 (36.4) | 43 (31.2) | ||||||

| CT value | −589.8 (−644.2, −478.6) |

−370.6 (−539.2, −144.4) |

<0.001 | −594.4 (−665.7, −508.5) |

−486.4 (−595.5, −365.4) |

0.001 | −483.5 (−614.5, −259.6) |

−353.7 (−538.0, −131.0) |

0.191 | |||

| Length (mm) | 6.00 (5.0, 7.0) | 10.0 (7.0, 15.0) | <0.001 | 8.50 (7.3, 10.0) | 10.0 (8.0, 13.0) | 0.021 | 8.00 (6.0, 8.5) | 12.0 (9.0, 17.0) | <0.001 | |||

Data are presented as median (IQR) or n (%). AAH, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia; AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ; MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma; IAC, invasive adenocarcinoma; SN, solid nodule; mGGN, mixed ground-glass nodule; pGGN, pure ground-glass nodule; LLL, left lower lobe; LUL, left upper lobe; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right upper lobe; CT, computed tomography; IQR, interquartile range.

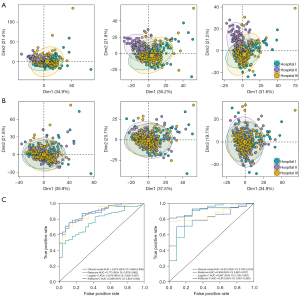

Construction and validation of the radiomics model

After coarse-to-fine feature selection, nonzero coefficient features were obtained for each region (including “original_glcm_MaximumProbability_0mm”, “wavelet.HHH_ngtdm_Coarseness_3mm”, and “wavelet.HHH_ngtdm_Coarseness_5mm”). Two radiomic features with a coarseness of 3 and 5 mm showed high collinearity (variance inflation factor >10), and the latter was eliminated, which resulted in a larger average variance inflation factor value. Finally, “MaximumProbability_0mm” and “coarseness_3mm” were used to construct the multiple-region radiomics model (Radnodule + 3 mm) using logistic regression. It had superior prediction performance, with an AUC of 0.791 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.718–0.852], as compared to the Radnodule, Rad3 mm, and Rad5 mm region radiomics models, with AUCs of 0.741 (95% CI, 0.664–0.810), 0.747 (95% CI, 0.672–0.815), and 0.776 (95% CI, 0.708–0.835) (Figure 3A), respectively, in the training cohort. Therefore, the radscore was determined using the prediction results of the multiple-region radiomics model.

Construction of the clinical model

Clinical and radiological factors, including CT value, tumor length, vacuolar, crescent, tumor vessel sign, and pleural traction sign, were significantly associated with pathological invasiveness in the univariate logistic analysis (P<0.05). Subsequently, three important factors (CT value, tumor length, and crescent sign) were selected using stepwise logistic regression to construct the clinical model (Table 2). The AUC of the clinical model in the training cohort was 0.851 (95% CI, 0.801–0.899) (Figure 3A).

Table 2

| Factors | Univariate logistic analysis | Multivariate logistic analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.291 | 0.685–2.545 | 0.443 | – | – | – | |

| Vacuolar sign (yes) | 3.379 | 1.294–11.600 | 0.026 | 3.208 | 1.040–12.423 | 0.060 | |

| Air bronchogram (yes) | 2.264 | 0.753–9.787 | 0.196 | – | – | – | |

| Crescent sign (yes) | 7.477 | 2.631–31.450 | 0.001 | 4.408 | 1.381–19.907 | 0.025 | |

| Tumor-lung boundary (yes) | 1.296 | 0.621–2.578 | 0.473 | – | – | – | |

| Tumor vessel sign (yes) | 3.153 | 1.388–7.050 | 0.005 | 1.415 | 0.492–4.159 | 0.520 | |

| Pleural stretch sign (yes) | 3.041 | 1.449–7.210 | 0.006 | 0.709 | 0.273–1.966 | 0.489 | |

| CT value | 1.005 | 1.004–1.008 | <0.001 | 1.005 | 1.002–1.008 | <0.001 | |

| Age | 1.021 | 0.996–1.047 | 0.100 | – | – | – | |

| Length | 1.435 | 1.272–1.651 | <0.001 | 1.214 | 1.048–1.440 | 0.017 | |

| Radscore | 2.718 | 2.038–3.761 | <0.001 | 1.524 | 1.071–2.262 | 0.026 | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CT, computed tomography; radscore, radiomics score.

Construction of clinical-radiomics combined model

Integration of the important factors and radscore, logistics, and the XGBoost algorithms was performed to construct the clinical-radiomics combined model. In the training cohort, the AUCs (Figure 3A) of the logistic combined (logistic-C) model and XGBoost combined (XGBoost-C) model were 0.853 (95% CI, 0.804–0.898) and 0.889 (95% CI, 0.848–0.927), respectively (Table 3). This indicated that the XGBoost-C model achieved a better discriminatory performance than did the clinical model, single-region and multiple-region radiomics models, and logistic-C model. Subgroup analysis of the models’ predictive performance based on nodule length was performed, the details of which are provided in Table S1.

Table 3

| Cohort | Model | AUC (95% CI) | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Clinical model | 0.851 (0.801–0.899) | 0.746 | 0.718 | 0.850 |

| Radscore model | 0.791 (0.718–0.852) | 0.757 | 0.778 | 0.683 | |

| Logistic-C model | 0.853 (0.804–0.898) | 0.768 | 0.759 | 0.800 | |

| XGBoost-C model | 0.889 (0.848–0.927) | 0.772 | 0.741 | 0.883 | |

| External validation I | Clinical model | 0.875 (0.808–0.936) | 0.756 | 0.720 | 0.885 |

| Radscore model | 0.773 (0.678–0.862) | 0.689 | 0.699 | 0.654 | |

| Logistic-C model | 0.876 (0.802–0.937) | 0.756 | 0.731 | 0.846 | |

| XGBoost-C model | 0.889 (0.823–0.942) | 0.773 | 0.742 | 0.885 | |

| External validation II | Clinical model | 0.810 (0.700–0.910) | 0.826 | 0.855 | 0.455 |

| Radscore model | 0.859 (0.687–0.977) | 0.711 | 0.703 | 0.818 | |

| Logistic-C model | 0.867 (0.792–0.937) | 0.826 | 0.855 | 0.455 | |

| XGBoost-C model | 0.915 (0.851–0.963) | 0.839 | 0.841 | 0.818 |

AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; radscore, radiomics score; logistic-C, logistic combined; XGBoost combined; XGBoost, extreme gradient boosting.

Interpretation analysis and application of the XGBoost model

The Shapley summary diagram in Figure 3B shows the contribution of four factors (CT value, radscore, tumor length, and crescent sign) in predicting the invasiveness of pulmonary nodules in each patient. The larger the absolute distribution range of the Shapley value is, the greater the importance of features in the evaluation of pulmonary nodule invasiveness. The first XGBoost regression tree-based decision heatmap in Figure 3C illustrates the features utilized by the tree and the means by which these samples are split in making final predictions.

The SHAP force plot can explain the evaluation of individual patients and be used to visualize the Shapley value for each feature as a force, which either increases (positive value) or decreases (negative value) the prediction from its baseline. The baseline is the average Shapley value for all the prediction features. The size of the arrow in Figure 3D indicates the contribution of a feature to the Shapley value, while the red and blue arrows indicate positive and negative, respectively.

Case application analysis of the XGBoost model

Two typical patients (Figure 3D), a 53-year-old man with AAH/AIS and a 42-year-old woman with MIA/IAC, were selected to analyze the XGBoost model. The pulmonary nodule of patient 1 had a high CT value [−328.5 Hounsfield units (HU)], high radscore (radscore =2.623), long length (12 mm), and a positive crescent sign, thus indicating a high SHAP value (2.41), which strongly suggested MIA/IAC and was consistent with the final pathological results. The pulmonary nodule of patient 2 had a low CT value (−583.8 HU), low radscore (radscore =0.058), short length (3 mm), and a negative crescent sign, indicating probable AAH/AIS with a low SHAP value (−1.40), which was also in line with the final pathological results.

Generalized validation of the predictive model

Two independent hospitals were retrospectively recruited, and the batch effect was eliminated. The data distributions of the three hospitals were relatively scattered before elimination of the center effects (Figure 4A), whereas these were pooled together following normalization using ComBat harmonization (Figure 4B). The AUCs of the XGBoost-C model were 0.889 (95% CI, 0.823–0.942) and 0.915 (95% CI, 0.851–0.963) in external validation cohorts I and II, respectively (Table 3, Figure 4C), indicating a satisfactory generalization performance.

Discussion

In this multicenter study, we constructed an interpretable XGBoost clinical-radiomics combined model incorporating important clinicoradiological factors and radscore to distinguish AAH/AIS from MIA/IAC. Specifically, the radscore was calculated by combining VOInodule and VOI3 mm information. The individualized contribution of each feature was visualized for each patient with the Shapley algorithm, which helped to explain the predictive power of the features in this model. Furthermore, the complex XGBoost combined model was visualized into a reliable clinical treatment decision support tool using the tree-based decision heatmap method that clinicians can easily apply. Finally, the predictive performances were successfully validated in two external validation cohorts via ComBat harmonization.

The invasiveness of tumors can cause changes in the morphology and microenvironment of the nodules (21), including in tumor length, CT value, crescent sign, convergence sign of pulmonary vessels, and pleural traction, and further lead to poor prognosis (8,22-24). In this study, tumor length, CT value, and crescent sign were considered useful features for predicting the invasiveness of pulmonary nodules, which was consistent with the findings of previous studies (3,25-27). In recent years, perinodular radiomics has been demonstrated capable of capturing microscopic information around pulmonary nodules. In line with the relevant literature (8,11,28,29), our results showed that perinodular radiomics also had a good predictive value for pulmonary nodular invasiveness, with Rad3 mm performing better than Rad5 mm. This might be because our nodules were relatively smaller and thus contained limited information for invasiveness, which was partly in agreement with the findings of Wu et al. (30). Interestingly, coarseness was selected as the optimal perinodular feature in both VOI3 mm and VOI5 mm. Coarseness captures texture information in the perinodular region, is positively correlated with lung cancer invasiveness and recurrence rate (31), and reflects the heterogeneity of the tumor. In our study, the performance of the multiple-region radiomics model had a higher AUC, which supports the feasibility of perinodular radiomics techniques for the prediction of pulmonary nodule invasiveness and proves the complementarity of tumor and perinodular tumor information.

The clinical-radiomics combined model was constructed using logistic regression and the XGBoost algorithm. In external validation I and II, the specificity of logistic-C model was significantly lower than that of the XGBoost-C model. The reason for this may be that first, we first ensured the generalization of the models and used the same cutoff value in training cohort and external validation cohorts; second, the sample size of the precursor glandular lesions in external validation II was too small, and there was a certain bias in the prediction performance of the model. However, the XGBoost-C model showed superior predictive performance and generalization, which could improve the accuracy of prediction. Additionally, the SHAP method was used to comprehensively analyze the complex relationship between features and nodule invasiveness. The detailed contribution of each feature was visualized for each patient with a pulmonary nodule. The CT value and radscore were found to be the two most important factors for predicting the invasiveness of the pulmonary nodule according to the maximum width Shapley distribution interval. All features were positively correlated with pulmonary nodule invasiveness, which was consistent with a previous study (32). After clinicians understand how features impact the XGBoost model, they might use the model to assess individual outcomes. Thus, for the first time, we plotted a classification tree-based decision heatmap to solve the “black-box” problem for the complex machining learning model and to intuitively illustrate the decision process of the XGBoost model and the interaction relationship between features. The tree-based decision heatmap will be more amenable to clinicians, as it can simulate routine decision making in the clinician’s practice. Two patients were included in the case analysis. The decision-making process was highly consistent with the diagnostic thinking of the radiologist, proving the feasibility and convenience of the model.

Our study has several limitations. First, it involved a retrospective design and thus potentially introduced bias. Second, for small pulmonary nodules, some tumor vessels, vacuoles, and bronchi might have been unavoidably included, which might have affected the results of some radiomic features. Third, considering that the average length of the nodules was only 10.4 mm, we focused only on perinodular regions of 3 mm (one-third) and 5 mm (half), and the larger regions were not included in our study. Potential future research directions may involve collecting more samples for hyperparameter optimization and iterative training and conducting prospective analyses to verify the accuracy of predictions and the generalizability of the models. Future research direction should focus on developing methods for visually displaying the prediction information of radiomics in images and highlighting the areas requiring attention so as to assist clinicians in decision-making.

Conclusions

We constructed an interpretable radiomics model for the preoperative assessment of pulmonary nodule invasion using the XGBoost algorithm. The contribution of each feature was quantified using the SHAP method and the model was visualized using a tree-based decision heatmap. The satisfactory generalization performance of the model was successfully verified in two independent external validation cohorts. Therefore, our radiomics model may help clinicians improve the assessment and management of patients with pulmonary nodules.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was supported by the grants of

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-23-615/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-23-615/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University (The First People’s Hospital of Shunde) (No. KYLS20220701), and the institutional review board waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study. All participating hospitals/institutions were informed and agreed with the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209-49.

- Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF, Heist RS. Lung cancer. Lancet 2021;398:535-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicholson AG, Tsao MS, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, Brambilla E, Cooper WA, Dacic S, Jain D, Kerr KM, Lantuejoul S, Noguchi M, Papotti M, Rekhtman N, Scagliotti G, van Schil P, Sholl L, Yatabe Y, Yoshida A, Travis WD. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:362-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Ma X, Shen X, Wang S, Li Y, Hu H, Chen H. Surgery for pre- and minimally invasive lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;163:456-64.

- Fan L, Fang M, Li Z, Tu W, Wang S, Chen W, Tian J, Dong D, Liu S. Radiomics signature: a biomarker for the preoperative discrimination of lung invasive adenocarcinoma manifesting as a ground-glass nodule. Eur Radiol 2019;29:889-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu H, Jiao Z, Han W, Jing B. Identifying the histologic subtypes of non-small cell lung cancer with computed tomography imaging: a comparative study of capsule net, convolutional neural network, and radiomics. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021;11:2756-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang L, Lin W, Xie D, Yu Y, Cao H, Liao G, et al. Development and validation of a preoperative CT-based radiomic nomogram to predict pathology invasiveness in patients with a solitary pulmonary nodule: a machine learning approach, multicenter, diagnostic study. Eur Radiol 2022;32:1983-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beig N, Khorrami M, Alilou M, Prasanna P, Braman N, Orooji M, Rakshit S, Bera K, Rajiah P, Ginsberg J, Donatelli C, Thawani R, Yang M, Jacono F, Tiwari P, Velcheti V, Gilkeson R, Linden P, Madabhushi A. Perinodular and Intranodular Radiomic Features on Lung CT Images Distinguish Adenocarcinomas from Granulomas. Radiology 2019;290:783-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, Parmar C, Grossmann P, Carvalho S, Bussink J, Monshouwer R, Haibe-Kains B, Rietveld D, Hoebers F, Rietbergen MM, Leemans CR, Dekker A, Quackenbush J, Gillies RJ, Lambin P. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun 2014;5:4006. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ren H, Liu F, Xu L, Sun F, Cai J, Yu L, Guan W, Xiao H, Li H, Yu H. Predicting the histological invasiveness of pulmonary adenocarcinoma manifesting as persistent pure ground-glass nodules by ultra-high-resolution CT target scanning in the lateral or oblique body position. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021;11:4042-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu Z, Xu C, Zhang Y, Ji F. A triple-classification for the evaluation of lung nodules manifesting as pure ground-glass sign: a CT-based radiomic analysis. BMC Med Imaging 2022;22:133. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng J, Gao M, Liu J, Yue H, Kuang H, Liu J, Wang J. Multimodal Disentangled Variational Autoencoder With Game Theoretic Interpretability for Glioma Grading. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2022;26:673-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Lang J, Zuo JZ, Dong Y, Hu Z, Xu X, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Yang L, Wong STC, Wang H, Li H. The radiomic-clinical model using the SHAP method for assessing the treatment response of whole-brain radiotherapy: a multicentric study. Eur Radiol 2022;32:8737-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma M, Liu R, Wen C, Xu W, Xu Z, Wang S, Wu J, Pan D, Zheng B, Qin G, Chen W. Predicting the molecular subtype of breast cancer and identifying interpretable imaging features using machine learning algorithms. Eur Radiol 2022;32:1652-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tseng PY, Chen YT, Wang CH, Chiu KM, Peng YS, Hsu SP, Chen KL, Yang CY, Lee OK. Prediction of the development of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery by machine learning. Crit Care 2020;24:478.

- Li R, Shinde A, Liu A, Glaser S, Lyou Y, Yuh B, Wong J, Amini A. Machine Learning-Based Interpretation and Visualization of Nonlinear Interactions in Prostate Cancer Survival. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2020;4:637-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu S, Chen R, Wei W, Belovsky M, Lu X. Understanding Heart Failure Patients EHR Clinical Features via SHAP Interpretation of Tree-Based Machine Learning Model Predictions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2021;2021:813-22.

- Zou Y, Shi Y, Sun F, Liu J, Guo Y, Zhang H, Lu X, Gong Y, Xia S. Extreme gradient boosting model to assess risk of central cervical lymph node metastasis in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: Individual prediction using SHapley Additive exPlanations. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2022;225:107038. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertsimas D, Margonis GA, Sujichantararat S, Boerner T, Ma Y, Wang J, et al. Using Artificial Intelligence to Find the Optimal Margin Width in Hepatectomy for Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases. JAMA Surg 2022;157:e221819. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lundberg SM, Erion G, Chen H, DeGrave A, Prutkin JM, Nair B, Katz R, Himmelfarb J, Bansal N, Lee SI. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat Mach Intell 2020;2:56-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nishino M. Perinodular Radiomic Features to Assess Nodule Microenvironment: Does It Help to Distinguish Malignant versus Benign Lung Nodules? Radiology 2019;290:793-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang T, She Y, Yang Y, Liu X, Chen S, Zhong Y, Deng J, Zhao M, Sun X, Xie D, Chen C. Radiomics for Survival Risk Stratification of Clinical and Pathologic Stage IA Pure-Solid Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiology 2022;302:425-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chu ZG, Li WJ, Fu BJ, Lv FJ. CT Characteristics for Predicting Invasiveness in Pulmonary Pure Ground-Glass Nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020;215:351-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SM, Park CM, Goo JM, Lee HJ, Wi JY, Kang CH. Invasive pulmonary adenocarcinomas versus preinvasive lesions appearing as ground-glass nodules: differentiation by using CT features. Radiology 2013;268:265-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kameda K, Eguchi T, Lu S, Qu Y, Tan KS, Kadota K, Adusumilli PS, Travis WD. Implications of the Eighth Edition of the TNM Proposal: Invasive Versus Total Tumor Size for the T Descriptor in Pathologic Stage I-IIA Lung Adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:1919-29.

- Borczuk AC. Updates in grading and invasion assessment in lung adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 2022;35:28-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Altorki NK, Borczuk AC, Harrison S, Groner LK, Bhinder B, Mittal V, Elemento O, McGraw TE. Global evolution of the tumor microenvironment associated with progression from preinvasive invasive to invasive human lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep 2022;39:110639. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen N, Li R, Jiang M, Guo Y, Chen J, Sun D, Wang L, Yao X. Progression-Free Survival Prediction in Small Cell Lung Cancer Based on Radiomics Analysis of Contrast-Enhanced CT. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:833283. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang X, Huang H, Du P, Wang L, Yin H, Xu X. Intratumoral and peritumoral CT-based radiomics strategy reveals distinct subtypes of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2022;148:2247-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu L, Gao C, Ye J, Tao J, Wang N, Pang P, Xiang P, Xu M. The value of various peritumoral radiomic features in differentiating the invasiveness of adenocarcinoma manifesting as ground-glass nodules. Eur Radiol 2021;31:9030-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen JG, Reymond E, Medici M, Lederlin M, Lantuejoul S, Laurent F, Toffart AC, Moreau-Gaudry A, Jankowski A, Ferretti GR. CT-texture analysis of subsolid nodules for differentiating invasive from in-situ and minimally invasive lung adenocarcinoma subtypes. Diagn Interv Imaging 2018;99:291-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu M, Yang Z, Wang M, Zhao W, Zhu Q, Shi W, Yu H, Liang Z, Chen L. A computerized tomography-based radiomic model for assessing the invasiveness of lung adenocarcinoma manifesting as ground-glass opacity nodules. Respir Res 2022;23:96. [Crossref] [PubMed]